Is it viable to self-publish your short fiction?

Alexander Chee is a well-regarded literary author who posted recently about the importance of submitting your stories to literary journals.1 He wrote:

I sometimes think about how the life I have, I have because I sent stories out to magazines. I learned early on that the writing I published brought me new friends, lovers, work opportunities, and that continues.

I don’t disagree with this sentiment. For a long time, I thought submitting your work (and weathering the attendant rejection) was the most important part of being a writer. On Dec 20, 2003, I sent out my very first story submission, and I have always dated the beginning of my writing career from that moment. I have submitted my work for 22 years, and I have 2,100 short story rejections (and sixty plus acceptances) to show for it.

But...less than two years ago, I started writing short fictions in a very different style than I’d heretofore used. I’d been reading the Icelandic sagas and a lot of pre-modern prose fictions, and I thought to myself, “I bet that I could write something like this. I could write down a tale very simply, just as easily as I’d speak it to a friend.”

I spent several months writing stories in this style. I knew something really special was happening: the stories were flowing quite easily, and they were different from anything else I’d ever written.

And then I asked myself, “Who could possibly want these stories?”

Sometimes editors just don’t want you

For twenty-two years, I had been submitting stories to literary journals, and nothing had happened. Even when stories were published, there was not much evidence that anyone had read them. I was certainly never a contender for awards or honors. Never won any contests, even the ones you pay to enter. And never broke into the top tier of literary journals—no Ploughshares or McSweeney’s for me. I was stuck.

Furthermore, as I was experimenting with these stories, I was in the midst of two book releases: a YA novel came out from HarperTeen in Jan 2024 and a literary novel from Feminist Press in May 2024. I had high hopes for both, and I hired an independent press agent to try and drum up some interest in these books. The agency did their job, and my publishers did their job too, but there was simply no interest. Nobody cared about my novels.

These novels were about various hot-button social issue, and they hit various demographic targets people claimed to be interested in. And they were also a form, the novel, that remained quite popular amongst ordinary readers.

But my new stories were not about intrinsically interesting stuff like that, and they were a form that nobody really cared about. So I thought, “If my novels failed, how can my stories possibly succeed?”

What passes without comment in Chee’s post is that he doesn’t submit his short fiction to editors anymore himself. It’s not clear why he stopped—he doesn’t say. But in my case, I found it very hard to keep coming back to the same editors, year after year, asking them to believe in my talent. I tried telling myself all the stories everybody knows, about people who break out later in their career (or are remembered after their death), but I had lost hope. It’s that simple. I just didn’t really think that good things would ever happen for me.

So instead of submitting my stories to journals, I started self-publishing them on my blog.

In retrospect, this decision seems insane!

Posting my tales on this blog has rejuvenated my career and done much more for me than anything else I’ve published in the last twenty years.

So it’s hard for me to remember that when I began self-publishing these stories, I had zero expectation that anything good would happen. All I knew was that this work deserved to be read by someone, and I felt that if I emailed a story to 600 people, then maybe forty or fifty of them would actually read it, and that would be a lot better than if I sent it off to collect another rejection from The Kenyon Review.

I sent the first story completely cold.2 And after it ended, I had an afterword where I wrote, “The above is an example of the kind of essay / story / tale pieces I’ve been writing in my spare time lately. Kind of unclassifiable, huh?”

I closed the post by saying:

Anyway, sharing fiction on this Substack is an experiment. I’ve just been writing so much lately, and I’ve gotten tired with the incredibly long and slow process for getting fiction published in literary journals. I hope my story doesn’t disappoint, but I guess I’ll see from the unsubscribe rate how / whether it works out.

You can feel the trepidation in this initial missive. I really thought my subscribers might rebel and unsubscribe en masse.

My most inspired early move was to attempt a bit of branding. I decided that I wouldn’t say my fictions were ‘short stories’, because that would give the audience a bunch of expectations that I wanted to avoid.

What I told people was the truth: I was writing in a form much older than the short story, and only superficially related to it. So instead of calling them stories, I’d use another name entirely: I was publishing ‘tales’.

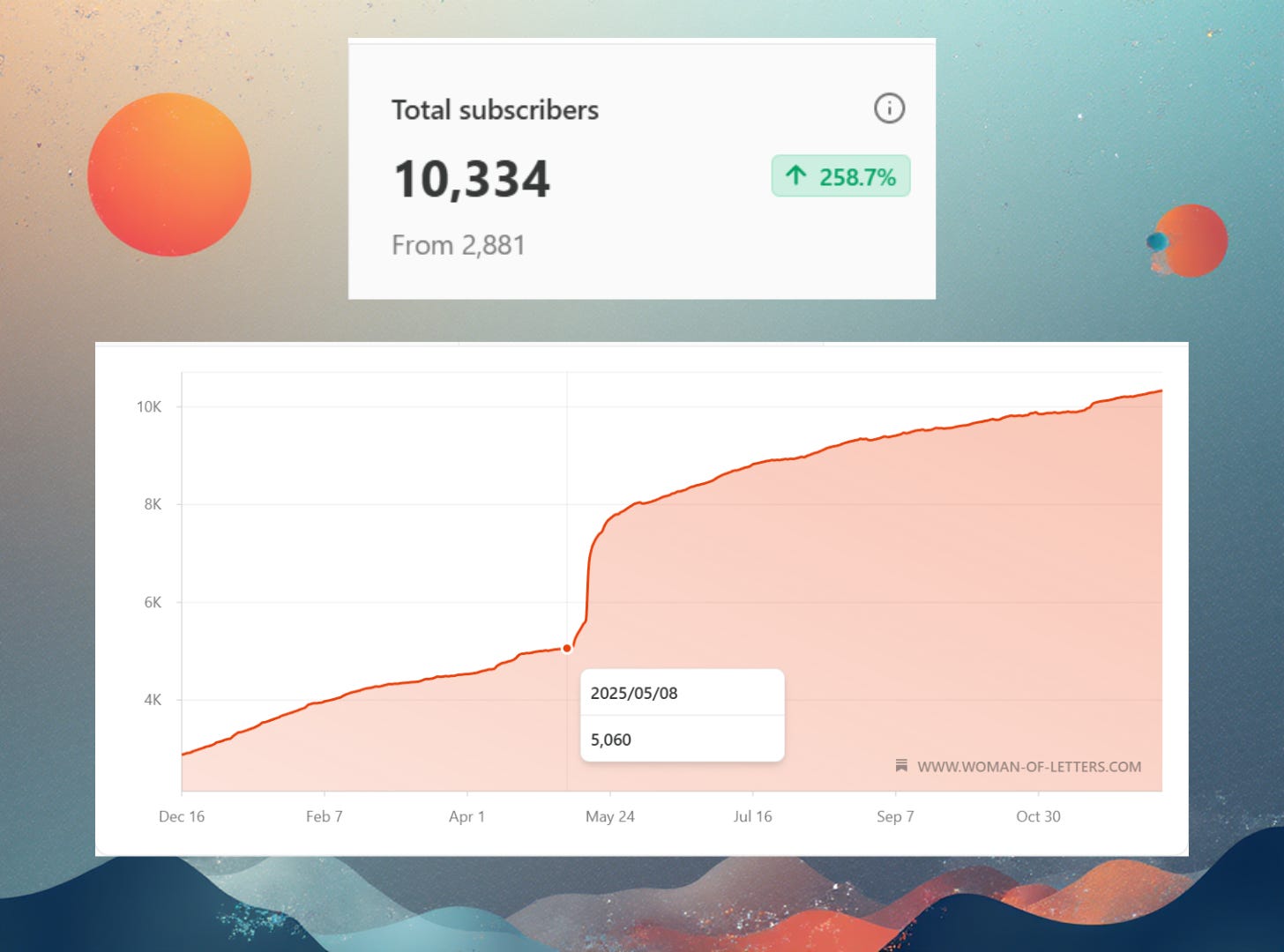

For a year, I posted these tales without any expectation that something good might happen. My newsletter grew exponentially in size, but the absolute number of subscribers wasn’t high enough to impress anyone. When I was at three thousand subscribers, an agent said my subscriber count wouldn’t be attractive to publishers until I hit ten thousand. After releasing my novella last November, I tried to pitch these tales to a few people, but the interest level wasn’t high.

Self-publishing has existed for virtually the entirety of my writing career. However, I conceptualized the self-pub world as consisting of tightly-knit communities who were avidly looking for work within certain niches (e.g. monster romance) that weren’t well served by big publishers.

My tales had no niche, no pre-existing audience, so I didn’t think they’d ever earn much money or gain a big readership. I was just doing it for the love, because I wanted to share my work. For twenty years I’d been a professional—someone who wanted to earn a living from their writing (and sometimes did!)—and now I was downscaling my ambitions and becoming something I’d never been before: an amateur. A person who wrote just for love.

And it was great!

Lately, by following Clancy Steadwell, I’ve become familiar with the community of people who post their fiction on Substack. I’ve gathered from them that it’s very stressful to share your fiction online: fiction writers on this platform are plagued by low engagement and low open rates. I’ve faced these problems as well: I’ve posted stories I loved and seen them get much lower engagement than things I thought were much better.

But, for me, that emotional toll is much lighter than the stress of submitting to journals. It’s no comparison at all. Out of every five stories I submit to literary journals, maybe one gets accepted. Then it takes a year for that story to appear, and oftentimes it gets no engagement, no reactions. With Substack, there’s no possibility of rejection, the story appears immediately, and even my least-read piece gets some comments, likes, shares, retweets—some evidence that people read it.

Self-publishing was also a great learning environment. When I was submitting to journals, I got mostly form rejections—I had no understanding of why a given story might not have worked for a given editor. But with Substack, I get granular information about what’s holding peoples’ attention and what’s not. Sometimes the information is uncomfortable: I love writing science fiction, but those stories tend not to perform well on my blog. However it’s information that I can actually use. I am much more in tune with my audience than I am with the editors of journals, and over time I’ve gotten increasingly good at catching and holding my audience’s attention.

Posting my tales online was a low-risk / low-reward activity. These are the kinds of activities I’d been socialized to avoid. I’d always believed that you take chances, take risks, and you hope for big rewards. Self-publishing didn’t feel like this. There was no risk. What was the worst thing that could happen? I had no chance of rejection, nor was there much hate or negative criticism (if people don’t like a self-published fiction they don’t bash it, they just don’t finish it).

The reason to avoid low-risk activities is that they usually carry little upside. With self-publishing online, what was the best thing that could happen? I could not conceptualize what success for this activity would even look like. I didn’t picture receiving any kind of mainstream critical attention. Indeed, the success of these tales relied on the fact that nobody took them seriously. Whereas a reader might be wary of a short story, they were less suspicious of these chatty, informal tales.

By May of 2025, I had about 5,000 subscribers. My growth had 10x’ed in a year, but I still didn’t have enough to make a publisher take notice. That month I began making plans to self-publish a collection, in the hope that this collection might be rediscovered in ten or twenty years and maybe I’d find a readership that way.

Then, in the second week of May, my novella, “Money Matters”, was reviewed by Peter C. Baker for The New Yorker.3

One good review can change your life

I understand now why everyone in my MFA was obsessed with getting published by The New Yorker. I didn’t even have a story in the magazine—I was just reviewed on their website—and my life changed overnight. I gained three thousand subscribers in a month, going from five thousand to eight thousand. I got a new agent and got a fair amount of editorial interest in publishing my collection. There was more mainstream press coverage, more interview requests. And even people on Substack started treating me differently—I suddenly got more praise, more engagement.

In the months since my big moment, I’ve come to realize my situation is not unprecedented. There are many people who’ve self-published their short fiction in various ways and gotten mainstream attention for it (Kelly Link, for example). And there are many people who’ve gotten attention for work published by very small or micro-presses. Lightning does strike. Chee is an example! His first book, Edinburgh, came out from a very small press that went bankrupt shortly after release, but the book was a hit and got republished in paperback by a big press.4

And oftentimes, though not always, there’s some element of social power underlying the seeming Cinderella story. You’re read initially by your friends and by your community. You have to impress them first, and then they amplify your work. If your friends have more power, more connections, then that amplification power is greater.

That’s why if you’re on the fringes of the lit world (not quite in and not quite out) one way of getting ahead is to start your own journal. You start a journal with a clear mission and a clear editorial voice, and this journal gets a lot of buzz. Suddenly it’s the journal to read, and a lot of influential people read it to keep current with the field. During the summer when I really grew as a writer, Substack became the place where there was heat, and more people needed to pay attention to it.

I say all this not to discount my talents, but because there were paths to success that I didn’t understand, which I only understand now, in retrospect. And I walked one of those paths without really knowing it.

Building the journal that I needed

Woman of Letters is just like N+1 or The Drift or The Metropolitan Review. It is a journal that offers a number of well-differentiated ‘verticals’ (article types) that are linked by shared worldview. And just like these journals, people have to buy into the whole concept. You subscribe, and then you get everything: you get the whole issue, you get every article.

All the above journals contain a mixture of book reviews, personal essays, literary essays, and fiction.

Woman of Letters is exactly the same. It has four verticals: essays about classic literature; reviews of contemporary books; personal essays and ‘takes’; and short fiction.

In Woman of Letters, the short fiction is quite unique and very different from any other journal. It’s a well-crafted product that maintains a consistent feel, even though there’s a lot of variation in style and content.

I’ve been reading many New Yorker stories, and what’s clear is that the editors of The New Yorker also had a very strong vision for the fiction section of their journal. They wanted to publish a particular type of story, with a particular feel, and they were not shy about communicating their vision to their writers—often doing so in voluminous rejection letters—and helping these writers to meet that vision. Much of the work of being a fiction editor at The New Yorker was finding writers who were able to consistently produce a product that comfortably fit the tone of the magazine.

There were often multiple fiction editors at the journal, and they published different kinds of writers. Not every story in the journal was the stereotypical “New Yorker story” about suburban angst. You had Robert M. Coates with his crime stories. You had Isaac Bashevis Singer, with his fables and fantasies and shtetl tales. You had Donald Barthelme, whose short fictions were often published in the spot the New Yorker reserved for humorous pieces. Writers had the opportunity to sell the journal on their vision, and the most successful writers were the ones who produced something uniquely their own, which nonetheless felt like it could’ve only been published in The New Yorker.

Some of these writers produced work that also stood alone. You can read Alice Munro without ever thinking about The New Yorker. Other writers, like Sally Benson or Alice Frankforter, produced stories that worked much better in the context of the magazine than independently. The smartest writers produced both types of stories. Cheever broke into The New Yorker with a lot of sketches in the early New Yorker style, but when it came time to produce his red book, he largely ignored these early tales in favor of his later stories that tended to be longer and more developed.5

It’s the same with me. I have tales that perform really well online and are shared widely—these stories build the audience for the tale style. But my legacy depends on this longer story, this novella, that didn’t actually perform particularly well or get much engagement in its initial publication. I was definitely happy with its readership, but it didn’t grow the journal as much as other early tales did.

Is it really viable to self-publish your short fiction?

After The New Yorker thing happened, I had two concerns. The first was to avoid portraying myself as some sui generis genius who was so good that they got plucked out of obscurity. I don’t think that’s accurate, and that’s not really what happened. I don’t think my novella, just plopped alone onto the internet, without the surrounding apparatus of this newsletter and without other tales to pave the way, would’ve gotten much attention. If you’re going to self-publish online, I think the key is to have a consistent fiction product, something that is always changing and improving, so that you’re continuously building an audience for your fiction and you’re not just waiting to be discovered. My original plan was to publish a novella every year, though this got short circuited by the New Yorker buzz.

My other concern was to not get distracted. I love running Woman of Letters. It is a lot of work to produce this newsletter, but it’s work that I am happy to do. The tales are my baby—they’re the most unique part of the journal, and they require the most courage and the most vision. But they’re not actually the most work. The nonfiction part of Woman of Letters takes maybe 75 percent of my effort, and the tales only 25 percent.

The nonfiction pieces really anchor the Woman of Letters value proposition. Because of these nonfiction pieces, I am confident that anyone who subscribes to the journal is getting a good deal—they’re learning something that is valuable to them. Otherwise, I’d worry that I’m just sending them an endless stream of stories that they don’t really want.

My readers have different orientations to my fiction, and for many of them the tales are not the major highlight. That’s the same as for any journal—there aren’t many people reading The New Yorker just for the stories.

But the tales are also critical. They’re what make the journal valuable to me. The tales are my long-term investment in my own future. In ten years, nobody will care about my review of Big Fiction, but my unique voice as a fiction writer will still differentiate me from other writers. That’s the basic Woman of Letters bargain. Readers get high-quality posts about contemporary and classic literature, most of which aren’t paywalled, and in return I get to try out various experiments and see if I can catch their interest.

This is basically the bargain offered by most journals. They’re always trying something new, seeing if it’ll spark some interest, win awards, or grow their readership. But they also offer some core, reliable content that they know people will like. I do the same thing as any other journal, but I write all the content myself.

Which brings us back to whether it’s a good idea to submit your work to literary journals. Personally, I agree that writers need journals. But most of the pre-existing fiction journals are either highly-selective or moribund (and sometimes both!). That’s why I created my own journal, Woman of Letters, and it worked out pretty well.

It won’t work if you dislike the readers

One major reason I’ve succeeded on Substack is that I actually like the people I meet on this platform. In the literary world, I struggled to relate to people, because they were mostly excited about contemporary literature and I don’t read much of that. With LitStack—the literary corner of Substack—it’s completely different. There’s some kind of sympathy that exists between me and this community. People on LitStack tend to be suspicious of contemporary fiction, they tend to prefer small-press and older books, and they just have a very earnest, middle-class attitude toward literature. They really want to learn, understand, argue, improve themselves. It’s how I imagined the literary world would be, back when I was twenty-three and just setting out to read the Great Books.

I understand that many people don’t feel at home amongst this Substack community. They feel like it is argumentative and full of petty resentments. That’s fine. Those people should go find some other community where they do feel more at home. There’s no point sharing work with people you don’t respect: luckily, I really respect my readers and my peers on this platform.

When I started out, John Pistelli and Ross Barkan were both very welcoming. They read me, linked to me, recommended me. They’re not the only supporters I’ve had on this platform—BDM and Celine Nguyen and Henry Oliver and Sam Kahn and John Warner and Daniel Oppenheimer—but John and Ross both had good years, in exactly the same way that I had a good year, and it really feels like we grew together.

Both John and Ross released books this year, and during the run-up to their book releases I interviewed them for Woman of Letters. They both wrote big, ambitious books, and they received mainstream critical attention of the type that small-press books don’t normally get. One of my best experiences of the last year was hearing John Pistelli on Daniel Oppenheimer’s podcast.6 John seemed so happy with the year he’d had, and with the attention he was finally receiving. He really deserves every bit of it. He is one of the most generous people I’ve ever encountered—he really takes people seriously and treats them with respect, and I know I’m not the only writer whose life he’s touched like this.

Ross Barkan is also a consummate community-builder. He has given a home, in The Metropolitan Review, to a legion of writers who otherwise had nowhere to publish. He has given so many people their shot. There’s Alexander Sorondo, of course, who works at a grocery store in Florida, and moonlights as 2025’s most exciting writer of in-depth author profiles. But in the last few months alone, he’s published incredible essays by Theo Lipsky and Aled Maclean-Jones, two writers I’d never known before, but who I am sure have a great future ahead of them.7 He really trusts his writers and gives free reign to their vision. And he’s become a real friend—I am happy he’s in my life.

Celine Nguyen is also a phenomenon. I feel like I don’t need to sell Celine to you. I regularly meet women here in SF for whom Celine is their idol. She is an aspirational figure. She is so cool and so polished. I’ve learned a lot from observing how she operates on this platform. But she has also become a very close friend and has seen me through a lot.

I probably owe the most to Henry Begler . I think this is his first year of writing, but he taught me that it’s possible to write in plain language about iconic authors and to summarize them in a way that’s fair and dispassionate, a way that’s neither a glaze nor a takedown. A lot of what you see in the nonfiction pieces on my blog is my attempt to imitate what he does.8

There are countless other people who I’ve met through this journal. Some have become friends, like BDM and sympathetic opposition and Quiara Vasquez. With others, I remain merely their fan and admirer. I even pulled one of my closest real-life friends, Courtney Sender, into this Substack world.

Earlier this year, an article came out from Vox that was mostly about Pistelli, Barkan, Lincoln Michel, Matthew Gasda, and a few others on Substack, and it asked, in essence, What does this literary community stand for? I was quoted in the article, but I never really linked to it on this newsletter, because I didn’t have a great answer myself. This LitStack community isn’t a coherent artistic movement. It’s not linked by ethos, politics, or temperament. And there are many vibrant parts of literary Substack that were not mentioned in that article, whether it’s the internet princesses like rayne fisher-quann or the kids at The New Critic, or the alt-lit folks at Zona Motel, or whatever’s happening over at Romanticon.

I spent years trying to make sense of the world of literary journals, and that world just felt like the same few people talking to each other, with no room for people like me. But here there’s a sense of possibility, the feeling that if you communicate well, you can actually reach someone who might not otherwise hear about you.

The worm

But of course I’m bound to enjoy a place where I am popular and successful, right? If I’d been regularly getting published in those literary journals, I’d probably feel much more charitable towards them.

I don’t think submitting to journals is a waste of time. Maybe good things will happen! Journal publication is one of the few ways for someone without an MFA to get a legible lit-world credential. I definitely know people who didn’t do MFAs and submitted through the online slush portal to places like The Kenyon Review and got accepted. If that happens, you have a much easier chance getting an agent and selling your literary novel. So it’s certainly worth trying.

But if it’s not working out, then it’s also worth doing something else. Journal publication is not the only game in town, even for a short story writer.

This is my last post of 2025

Thank you all for reading! I appreciate your time and attention, and I think that I’m relatively careful with it.

At the beginning of this year I had around 3,200 subscribers, and I told myself that if I had 7,000 by the end of the year I’d be happy, and if I had 10,000 I’d be ecstatic.

I crossed ten thousand a few weeks ago, so I am duly ecstatic. Here is my graph: I’ve marked the approximate day when the New Yorker review landed.

This is also my ninetieth post of the year! Ninety!

Last year I wrote mostly about the Mahabharata, but over the Christmas break, I re-read Huckleberry Finn, and that started what I am sure my readers found to be a very strange pivot to 19th-century American literature. I went on a rampage, posting about Twain, James Fenimore Cooper, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Washington Irving, Richard Henry Dana, Herman Melville [1, 2, 3, 4], Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Susanna Maria Commins.

At some point I felt like I’d run out steam with 19th-century America, and I was going to pivot to something else (I toyed with finally reading Tristram Shandy). But then...I read Raymond Carver, and I went on another tear, writing all about short stories and the 20th century American magazine world. I used various authors as a vehicle for writing about different aspects of the early 20th-century publishing world. There was O. Henry (commercial short fiction), Robert E. Howard (the pulps), Raymond Carver (MFA fiction), Edna Ferber (middle-class realism), and John Cheever (the New Yorker story).

I also tried my hand at a listicle, my list of the best classics-reprint publishers, which I thought came out really well. And I did some essay-writing too—the best and most popular of my essays this year were my long pieces about pathways to a highbrow literary career and about the different strands of the Western-fiction genre.

Last year I wrote a lot of angry pieces about the publishing industry, but at some point I realized that most of my readers are not writers, and that meant most of them didn’t really care about my various petty resentments towards the industry. So this year I swore to write about the industry in a more objective, even-keeled, accessible way.

That meant I wrote fewer discourse pieces this year, but I think they were higher in quality. The best was my male novelist discourse take: my opinion was that clamoring for more male novelists is basically identity politics, but I engaged in identity politics when it was good for me, so fair is fair. My pieces on Big Fiction and on Ocean Vuong’s Emperor of Gladness also piggy-backed off some strands of literary discourse.

And I wrote a weird, unclassifiable discourse post about how high-brow literature has a fandom. What I was trying to articulate in that post is that the audience of sophisticated readers is much broader than the audience for contemporary literary fiction. Because lit-fic is a shrinking, failing genre, the people who write in that genre often start to think that audience for literature is equally anemic, but I don’t think that’s true.

This year I experimented a lot with my tales, because my ambition was to turn them into drivers of subscription growth (i.e. I wanted to write tales that might potentially go viral and reach a broader readership). I tried various experiments along this line. I wrote a number of first-person tales. I started writing linked series of tales. And I tried experimenting with different forms and different sorts of endings.

What has worked best for me is to write short, realist tales that have cunning endings, which I sometimes steal outright from O. Henry stories. I’ve written three of these, all of them much more popular than the average tale.

My most popular tale this year was a discourse tale, piggybacking on ‘college kids can’t read’ discourse. It’s the most-liked and most-read post of my entire blog! I was surprised, I can’t say exactly why this one caught on so deeply. I think it’s because people actually do enjoy reading takes, but they’re also happy when a take moves in an unexpected direction. I’ll have to think harder about how to replicate this success.

With tales, it’s up-and-down. I’m always experimenting. Some things work really well, other things not so well. My most sustained series was my four Johanna tales—autofictions where I worked out my frustrations about the Trump regime. These usually got a lot of engagement, but they also lost me about 40 or 50 subscribers (each), because my newsletter until this year was very non-political, and I think some people don’t like to read about Trump stuff (which is fair enough).

I also posted three tales about Erdric, the Paladin who’ll lose his powers if he has sex; two about Darren, the nerdy male novelist; and two about the teenage boy living in the unnamed fascist country (that’s definitely not America). I think that I’ll probably continue the teenage boy series at some point and perhaps develop it into a novel, but we’ll have to see.

But some of my best tales this year were the stand-alones: my pseudobibliographical tale “Lonely Island Adventures” where I invented an entire fake genre; my tale of the burgeoning Indian immigrant community on Mars; and my story about what happens when DEI hits a school for sexy sorceresses

See you on January 6th

And that’s about it! I read many books. Not sure about the exact number, because I haven’t counted. But I’ve written on my blog about most of the important ones.

My newsletter’s growth was insane—my subscriber count increased 250% in one year. Most of that was due to The New Yorker mention. In the month after, I got 3,000 new subscribers. I don’t really think I can generalize much from that experience—certainly not enough to give advice to anyone else about how to replicate it.

Thanks so much for reading me! You definitely don’t have to, and I’ll understand if you stop, but I appreciate your attention. A year and a half ago, I started posting my tales on this newsletter, and that moment was a real low point for me. The success of this newsletter has been an incredible, unforgettable experience. I love working on it, and I hope that I can continue to do so for a long time.

Next year, I have a book coming out! **What’s So Great About The Great Books **is out May 19th from Princeton University Press. It’s my thoughtful defense of the Great Books movement. If you can imagine an eighty thousand page book where I lay out the arguments both for and against reading the classics, then you’re basically imagining this book. It’s a pretty good book! There’s really nothing else like it, that’s written by and for the autodidact.

If you preorder the book, it’ll go a long way to convincing my publisher that they should do a bigger print run.

Eighth Sam Richardson finalist announced!

True story, this award only arose because someone in my subscriber chat clued me in to the existence of an award for best self-published fantasy novel. I looked up the award and thought the structure was so elegant. Then this subscriber, Ani N, suggested that we do something similar for literary fiction!

Ani offered himself up as one of our judges, and now he’s announced his pick finalist pick, Eric Giroux’s Zodiac Pets:

Zodiac Pets is a piece of metafiction, featuring a college student named Wendy Zhao writing her senior thesis on the dramatic events of her middle school life in suburban Massachusetts. The mystery of the novel revolves around the town newspaper (run by a lonely ideologue and staffed by middle schoolers, including Wendy), and a conspiracy involving the town Wendy lives in. The meta-narrative features our protagonist improving her thesis through revisions and interviews with fellow newspaper staffers, while the main story is the story of the events of that time, structured in the form of the supposed senior thesis.

I am excited to read it! You can also check out our other finalists below.

Elsewhere on the Internet…

I did an interview with Sam Kahn at Republic of Letters. He’s a great interviewer. I admire his chutzpah. He asked me how I make money! That’s great—nobody else does that kind of thing. You can check out the interview here:

How far afield do you now feel from the current literary mainstream? How committed are you to being in a kind of alternate literary space?

It’s hard to tell. I can see my own subscriber list, so I know that a good portion of my subscribers are authors, editors, agents, critics. I have a number of subscribers who are editors for places that I would never even consider pitching, because they’re much too austere and difficult to break into.

…I think this highbrow, prestigious end of the business can be very resistant to salesmanship. It’s different from commercial fiction in that way. With commercial fiction, if you come to an agent with a very commercially-viable book idea, they’re always interested. With highbrow stuff, there’s more suspicion—there’s a feeling that if you were really good, you wouldn’t need to be selling yourself. That means once I started to maintain distance from the industry I became a little more attractive to it.

Chee wrote about story submissions in his recent post “What do you do with your stories”. Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah wrote a response post, which reiterated the importance of journal submissions, called “In defense of submitting”

The first story was called “Therapy isn’t the (only) answer.”

Chee’s highly-inspiring story about Edinburgh is related in this old post at The Awl.

I found an editor at a small press on my own a few months later, at a panel we were on together at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop (communities matter, is a lesson to the side here) and when, to my shock, he said he wanted to publish it, he referred me to someone we’ll call Agent 2, who drew up the contracts.

Things finally went well for my first book, scouts were excited, reviews went well, the paperback rights went to an auction that had publishers who’d rejected it in hardcover asking to see it again (11 of the 18 asking to see it had rejected it).

And then my small press went bankrupt, owing me a great deal of money from the Picador sale and it seemed I’d never get it. Agent 2 said, essentially, I can do nothing for you there. I fired her, because I needed someone who could do something for me.

To confirm this statement about Cheever’s early work, I went back and read Cheever’s first story in The New Yorker, and I was shocked by how good it was. Even from the beginning, this guy knew how to do it.

The podcast episode with John Pistelli and Daniel Oppenheimer was called “Rust-Belt Hero”. I really like Daniel’s podcast by the way. He’s another person who’s been very welcoming to me.

Theo’s piece is about Herman Wouk’s “The Caine Mutiny”. Lipsky says there should be more novels that valorize people who obey the rules. Aled’s piece is a review of the latest Mission: Impossible movie. It seems impossible that such a review could be good, but it’s a great piece of rhetoric: he starts tossing in Merleau-Ponty and all kinds of philosophers, but plays the joke completely straight, no winking at the camera.

The Begler piece that really opened my eyes was his review of J.D. Salinger’s output. I was like, oh wow, if you can re-evaluate Salinger, then you can do it to anyone.

You've had a truly awesome year on here. I'm one of the thousands who arrived after the New Yorker review. My favorite post of yours since then was your review of Big Fiction. Excited to see what's coming in the new year!

apparently i'm in the minority here, but the tales are what i like most about the newsletter. sometimes the other pieces really hit if they happen to be about something that speaks to me, but the fiction is always interesting.

congrats on your great year :)