We need myth-makers, not just myth-busters

From the ages of ten to twenty-two, I exclusively read science-fiction and fantasy novels. And these novels are almost always about exceptional people whose talents are, for whatever reason, not recognized by their existing milieu. As a result, they travel to some different society or engage in some kind of adventure, in which their true value is demonstrated.

When I was younger, I literally wanted to be a sci-fi hero. I wanted to go to space. I wanted to travel to different countries. To have adventures. But, like many sci-fi fans, I was bookish and shy—not really the adventure-having type. So instead I sublimated these desires and decided I wanted to be an art-hero. I would write great novels, and that's how my exceptional talents would be recognized.

I wrote a few science fiction novels, but after starting an MFA in creative writing, I fell out of love with science fiction. I decided the genre only existed to flatter the prejudices of its readers. The readers were like me, we all thought we were secretly exceptional. And the most successful writers were the ones who somehow fed that belief. Something about this didn't seem respectable to me.

I kept thinking, "What if we're not exceptional. What if we're ordinary? What then?"

What if a regular boy, who didn't have secret magic powers or martial ability, was sucked into a fantasy world?

I spent years trying to write various versions of this trope. And it never quite worked because...it's obvious what would happen: they would die. They would encounter some magical foe and be killed.

To survive exceptional circumstances, you need to either be very skilled or very lucky (or both). And if I was committed to writing about people with ordinary luck and skill, then I couldn't write about exceptional circumstances. That's why all my published books have been realist novels—they're the only kinds of stories that I could make work.

Falling back in love with exceptions

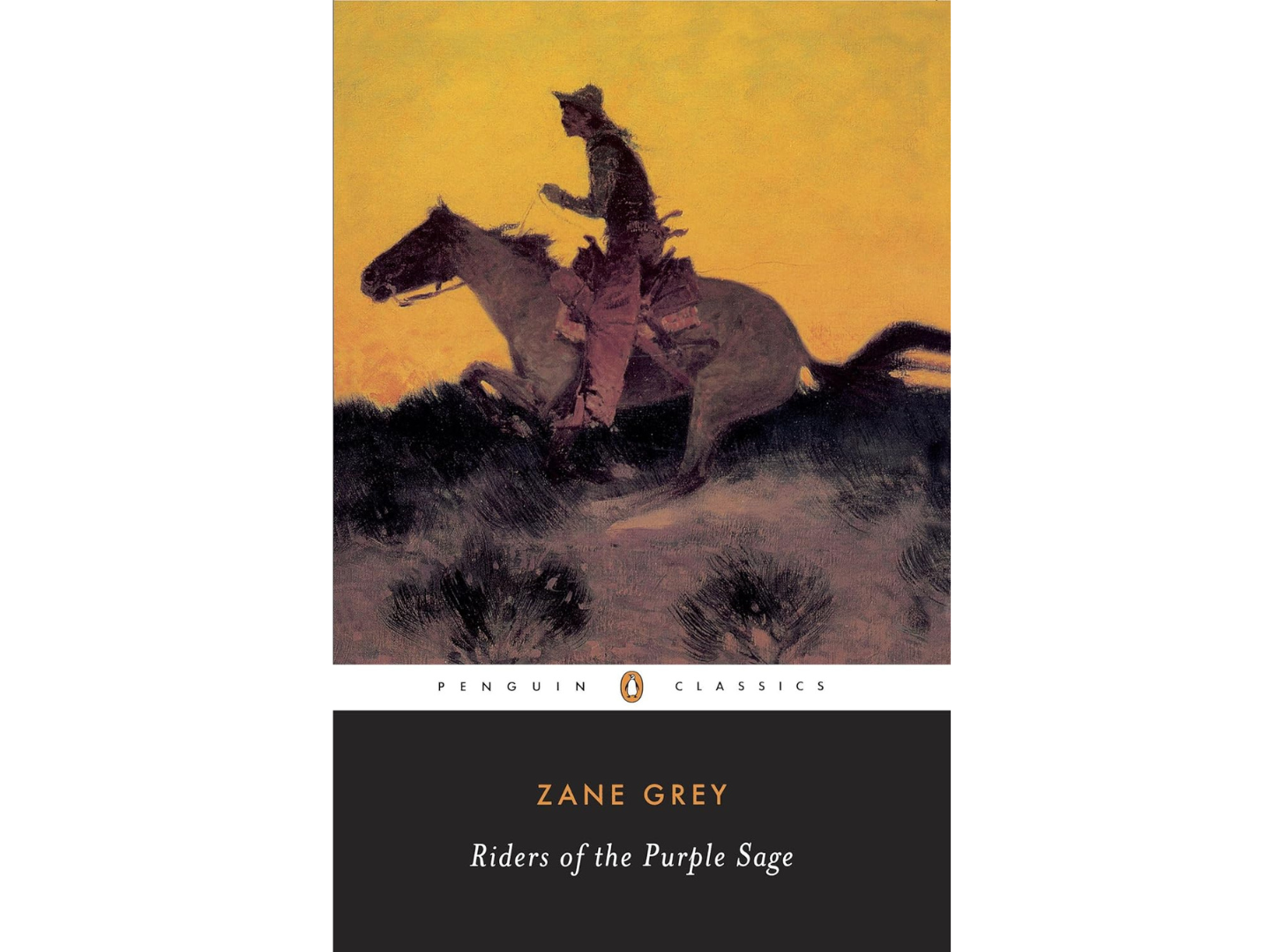

But about a month ago I decided to investigate the Western. And this led me to read the foundational text in the genre, Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage (1912). The book is about a Mormon woman who teams up with a lone gunman to resist a local magnate who’s trying to pressure her into marriage. And this novel really brought back my childhood memories of being enthralled by sci-fi stories.

That’s because these novels, these Westerns, deal with a core fantasy that is similar to the core fantasy that animates sci-fi novels. In Westerns, the fantasy is that in a world without the rule of law, a certain kind of skill and courage and goodness would rise to the top of society.

For the past fifty years, our highbrow literary culture has done its best to interrogate and deconstruct these kinds of fantasies, but…are they actually untrue? Obviously, every society goes through periods of lawlessness or anarchy. During these periods, people struggle to reassert some kind of order. And during these periods—goodness quite often wins. It’s not at all uncommon, during these periods, for moral leaders to arise who sway the people, through their skill and cunning and personal goodness, and set society back on track.

This is a process that is well-represented by the most famous literary work of all time, the Gospels. These are stories about a man who is alive during a time of political and religious tumult—a time when old myths have become unsatisfactory. And this man has no martial strength. He has no army. He has no church. Even his magical powers are somewhat marginal. He can’t really use them to kill his enemies. Instead, he has the power of his personal goodness and his dramatically different moral approach. Whether it’s healing the unclean woman, cleansing the temple, or saving the adulterous woman—he behaves in ways that radically contradict existing authority and moral teaching. And he succeeds, changing the world.

The Gospels are the core story of the West—the story that’s at the root of all our other stories.

In The Mahabharata, there’s something similar. You have Yudhisthira, who is personally not as strong as his opponents. But he is the Dharma Raja—the Dharma King. He understands dharma better than anyone else on earth; he has more wisdom than anyone else on earth. As a result of this wisdom, he gains the following of the world’s most powerful people, whether it’s his brothers or Krishna or the various Gods, and he ultimately prevails.

Goodness has power in itself. Goodness, by itself, can prevail over evil

And that’s also the story of the classic Western. In all of these books, there are evil lawless people with guns—and those people outnumber the heroes, but the hero, because he devotes himself to what is right, is able to prevail in the end.

It’s an extremely powerful story, and it’s one that has been lost, at least in the literary world, because in the literary world authors are often celebrated for tearing down myths instead of building them up.

The Death of the West(ern)

The most famous thing about the Western is that, as a literary genre, it has died.

Yes, novels are still published that have Western themes, but what has vanished is the dedicated Western reader. There are no readers left who will sit down and read Western after Western, week after week, month after month.

Genres exist in order to serve these dedicated readers. Right now, there are several genres that have readers like this: romantasy, mysteries, romance, domestic thrillers. There are many people out there who are willing to read 10 or 20 books from these categories in a year.

When you have dedicated readers like this, it creates opportunities. Not only do these readers drive a lot of sales themselves, but they also create room for midlist writers. If folks are only going to read one book in a particular category in a year, they'll probably read whatever is the biggest, most popular book. If you've only read one domestic thriller, you've probably read Gone Girl. But if you're going to read twenty of these books, then suddenly you have room for a lot more writers.

But of course the genre is also a straitjacket, and it's often experienced as such, because the most popular writers in the genre tend to be those who meet genre expectations most closely, and the success of these writers means publishers often put pressure on other writers to conform more closely to what the bulk of readers seem to want.

Once these dedicated genre readers disappear, the genre disappears as a coherent entity. In the aftermath of its collapse, a genre or a literary tradition is remembered because of just one or two examples. For instance, early Weird Tales is remembered primarily because of H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. These two writers stand in for a huge number of other writers who appeared in the pages of this journal.

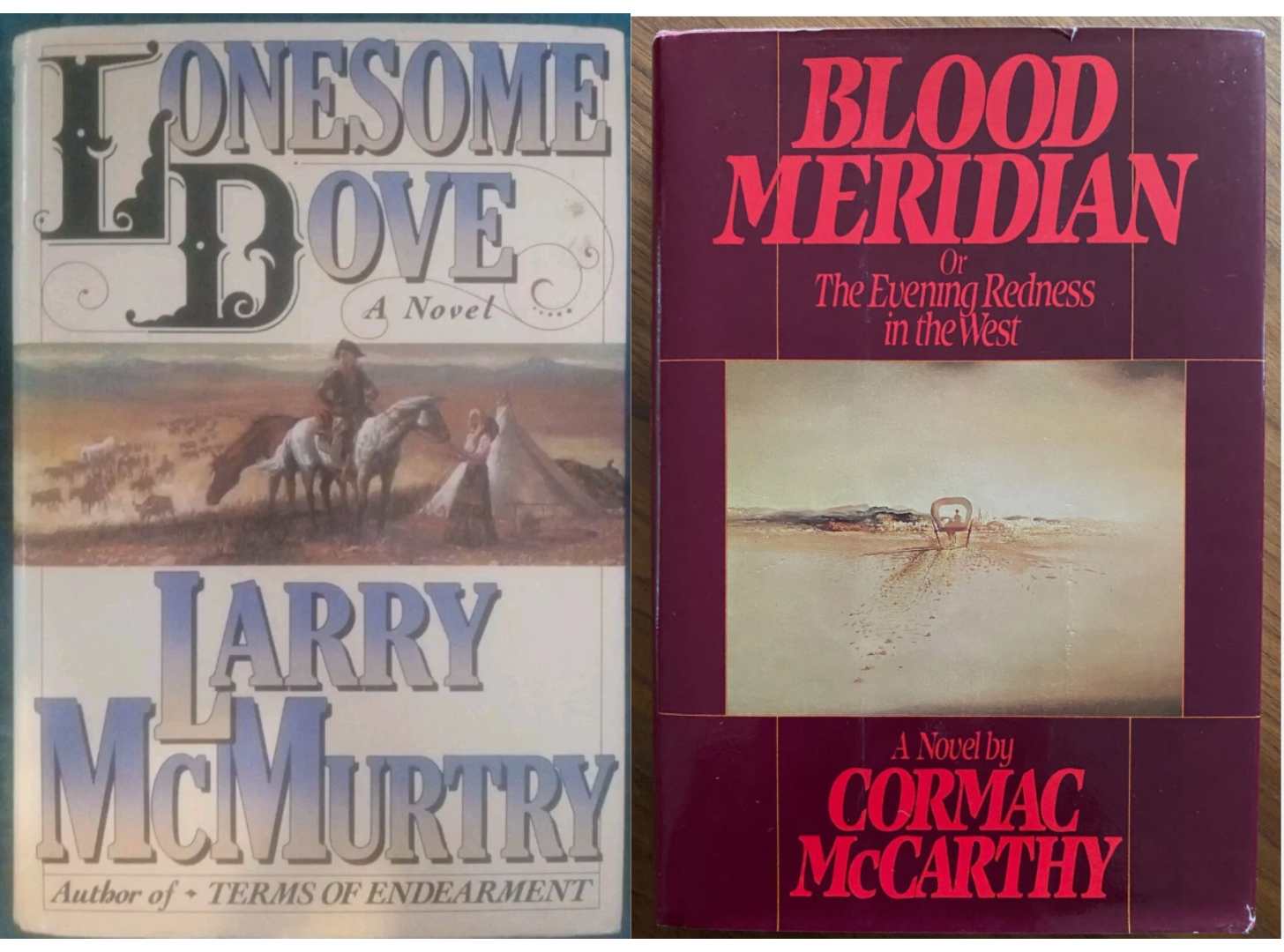

When it comes to the Western, this picture is even more complicated, because today the Western fiction is primarily associated with two writers, Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry, who didn't really write for an audience of dedicated Western readers, and who were both extremely cagey about their relationship to the Western genre.

Moreover, both of these writers published their defining works in 1985, when the Western genre was already in terminal decline, and both these books are celebrated primarily because they call into question many of the fantasies that underpinned the Western-fiction genre. As such, it seems silly to say their books were Westerns, because although they used Western themes, they were written outside the cultural and economic context that produced most written Westerns.

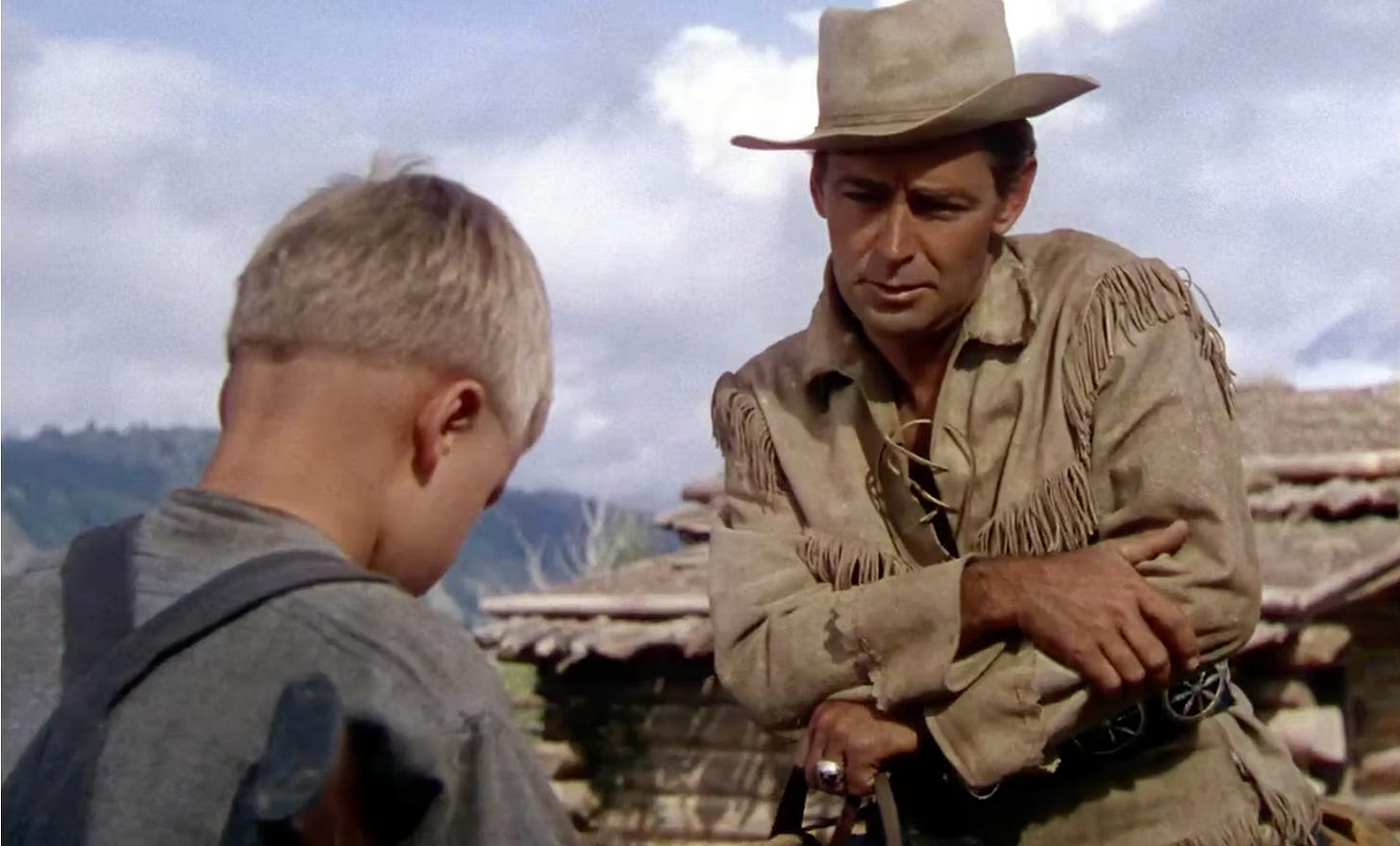

In my reading, I really tried to look for other novels that are of equally high quality, but which are more respectful of classic Western themes. And my belief is that I’ve found at least one: Jack Schaeffer’s Shane.

But the story isn’t as simple as saying literary books came along and messed up a classic genre by deconstructing it. That’s because the best of these classic-style Westerns, like Shane, were not actually considered un-literary when they were published. In fact, when it comes to the Western, the whole concept of literary and commercial has a very complex history that it’s taken me at least a month to understand.

The first Western

Genres are often formed due to the influence of a single bestseller. In 1912, a book called Riders of the Purple Sage was released. Zane Grey's novel wasn't the first book with Western themes, but it does seem, in my opinion, to be the book that really created the Western formula: a woman is being victimized by evil, the law is helpless, there is a danger that brute force might win out over justice, but then a lone gunman rides to the rescue, supports the force of right, and uses his strength of arms to ensure that justice wins.

Riders of the Purple Sage is so excellent. It's immediately compelling. It's told largely from the point of view of Jane Withersteen, a Mormon, who is being terrorized by one of her church elders into acceding to a marriage she doesn't want. She gives shelter to a gunman named Lassiter who's on a mysterious mission of revenge (he's hunting the man who abducted his sister). The woman pleads with Lassiter to put aside his guns, but he says:

Gun-packin’ in the West since the Civil War has growed into a kind of moral law. An’ out here on this border it’s the difference between a man an’ somethin’ not a man...Why, your churchmen carry guns. Tull has killed a man an’ drawed on others. Your Bishop has shot a half dozen men, an’ it wasn’t through prayers of his that they recovered. An’ today he’d have shot me if he’d been quick enough on the draw. Could I walk or ride down into Cottonwoods without my guns? This is a wild time, Jane Withersteen, this year of our Lord eighteen seventy-one.

Of course, Lassiter falls in love with Jane and takes her side against her community, and they eventually win out in the end.

Lassiter and Jane are an electrifying pair. They light up the page. It really does feel, when you're reading this book, like something new is happening. The book is also noteworthy for its attention to the landscape, and the way it evokes the many colors of its desert setting, but without the storytelling the landscape description would fall flat.

It's not important who was first

Many would say that Riders of the Purple Sage is not the first Western. They would say that honor belongs to Owen Wister's The Virginian. This 1902 novel was a runaway bestseller. It also features a rough cowboy type who fall in love with a more refined woman. That book is also powered in part by her abhorrence of violence: in the novel's most gripping sequence, the titular Virginian participates in the lynching of some cattle rustlers, and when his girlfriend learns about these events she is quite horrified.

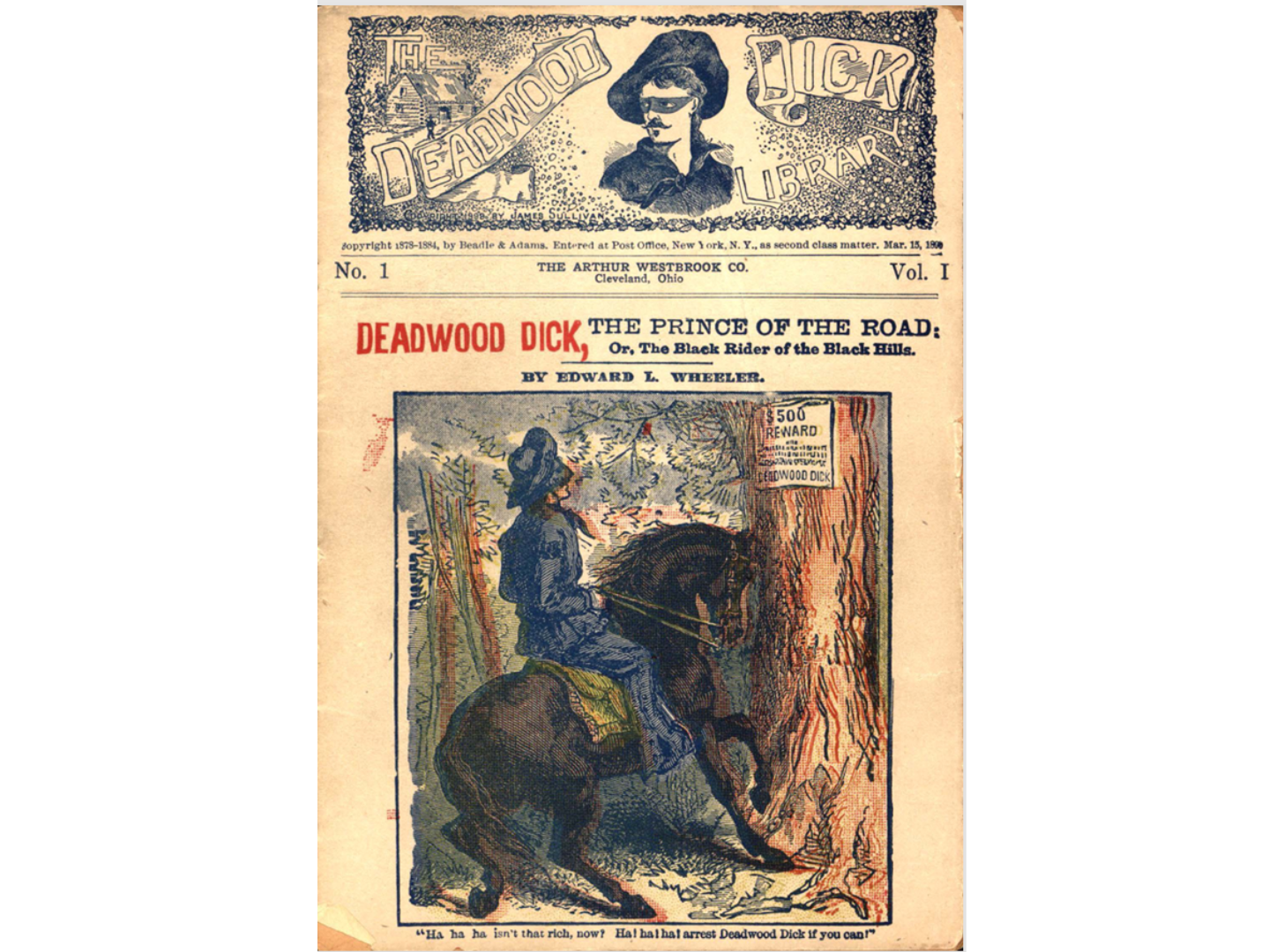

But...Wister's novel couldn't really be first, because it was preceded by the dime Western. The dime novel was a cheap pamphlet, often under 100 pages, with a soft cover—it was often sold at news-stands and general stores. This format was popular between 1860 and 1915, and Western themes were common amongst these novels. I read one of these books, Edward Lytton Wheeler’s Deadwood Dick, Prince of the Road. This dime western was published in 1877—it takes place in Deadwood, South Dakota, and it is all about these mythic heroes (Calamity Jane makes an appearance) saving women and fighting against railroad barons. These books strongly resemble Western fiction, at least to me, but for some reason aren't considered the start of the Western genre.

I don't think it's that important to debate where the Western genre arose. Obviously there is a lineage here, some set of themes and symbols that was transmitted through the written words. In many cases, newspaper stories and travelogues were probably an equally effective transmitter of the myth of the West. Earlier this year I read Mark Twain's Roughing It (1872), his account of his years as a prospector and journalist in the West, and his book is full of stories of gunfights and outlaws.

Butt Zane Grey was the writer who successfully shaped this material into a formula that other writers could copy: the mythic Western—the archetypal Western story about a woman who lives in a place where the law is powerless (or evil), and where she is menaced by bad men; a woman who is ultimately saved by a good man with a gun—a man who, despite his commitment to violence as a way of life, is somehow able to choose the side of justice.

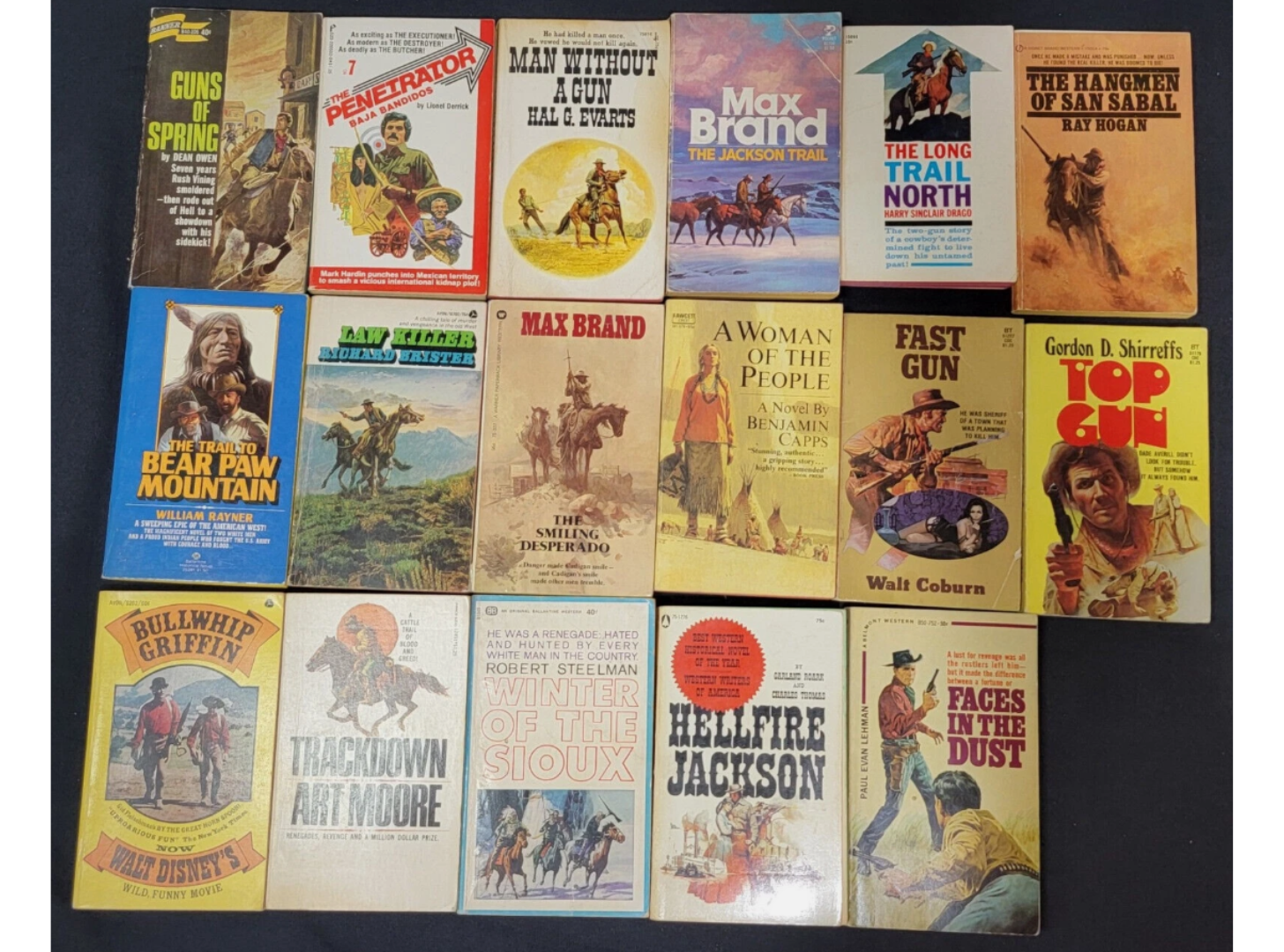

This formula became very popular. Zane Grey himself wrote over 100 novels and became the best-selling novelist of the 1910s and 1920s. A number of Western pulp magazines appeared in order to capitalize on the audience for this kind of fiction, and a few writers who came out of that pulp tradition—Max Brand and Luke Short—became bestselling writers in the 1930s and 1940s.

The myth of the West relied on cheap paper

The story of the Western is intricately tied up with the changing formats in which fiction was delivered to Americans. Hardback books—bound volumes with hard covers—have a long history in America. But these books are relatively expensive. A hardback volume cost a dollar. A dime novel would have perhaps half as many pages, but only cost ten or fifteen cents.

The kind of reading that powers the creation of a genre—the kind where you consume many different books that share the same formula—is somewhat price-sensitive. That's why genres first tend to coalesce around cheaper formats. This is true even today. Modern romantasy has strong roots in fan-fiction, which is free to read online, and self-published kindle novels, which often cost only $2.99.

In fact, for a long time, genre didn't really exist in the world of hardback books. Until sometime in the 1970s or 1980s, hardback novels were shelved together in bookstores, in a single fiction section. It was really in the softcover formats that the concept of genre started to take shape. During the 19th-century, a number of softcover fiction formats appeared: most notably, the penny dreadfuls, story papers, and dime novels. These were different formats, but they were all basically different kinds of pamphlets and newspapers that were sold at newstands, drugstores, and general stores.

And it was in the dime novel, in particular, that the Western really took shape as a genre.

The story of the Western runs through three softcover formats: the dime novel (1870 to 1915), the pulp magazine (1915 to 1955) and the Western-fiction mass-market paperback (1955 to 2000). These formats all succeeded each other and used similar distribution channels—they tended to be sold at news-stands, general stores, railway stations, especially in small towns or suburbs where there weren’t many bookstores.

During all of these eras, there are a number of writers who published primarily in these formats. Edward Lytton Wheeler published dozens of dime westerns between 1877 and 1897. Max Brand serialized most of his novels in pulp journals: All-Story, Argosy, Western Story, and a number of other pulp journals. In the mid-20th century, several publishers (Bantam, Ace, Signet, and Gold Medal) established Western lines that would publish paperback originals: novels that appeared first in paperback without ever appearing in hardback or serial form. The most famous writer to be published as a paperback original was Louis L'Amour, who is also, by far, the best-selling writer of Western fiction.

The other tradition of Western-fiction

But the complicated thing about the Western is that cheap, popular Westerns aren't the only Westerns. There is another literary tradition that runs parallel to the above: the mainstream novel with Western themes. These are books that look and feel like Westerns, but aren't necessarily written for the Western audience.

A modern-day parallel might be the science fiction novel. Nowadays, in America, we have a genre sci-fi tradition that draws a line of descent from Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, and all those guys, and this style of science fiction appeals to a relatively small audience that tends to read a lot of these books.

And then there's also a mainstream science fiction tradition, books like Annie Bot or Station Eleven. And these books tend not even to be shelved in the sci-fi section of the bookstore. They're in the General Fiction section, because they're not geared towards the genre sci-fi reader.

In the same way, there are a number of Western novels that are not really part of this genre tradition that I am talking about. The classic examples are Blood Meridian and Lonesome Dove (both 1985). Neither of these authors had written for the Western pulps. Neither of these books were published by Western-fiction paperback imprints. Instead, they were published in hardcover originals by mainstream publishers. And these hardcover-first novels often (though not always) pride themselves on the way that they complicate or deconstruct or evade the Zane Grey Western-fiction formula.

The pulp tradition didn't make it into the canon

During the hey-day of the Western-fiction genre, there was a certain element of mixing or cross-over between genre Western and the mainstream Western. For one thing, during the 1910s through the 1930s, many novels that were originally serialized in pulp journals (e.g. the novels of Max Brand and Luke Short) were reprinted in hardcover, where they often became huge bestsellers.

However, books with these pulp roots usually weren't taken seriously by the literary establishment. Max Brand and Luke Short were virtually never reviewed by mainstream journals and got no literary/critical attention. Zane Grey got a little attention, particularly towards the end of his career, but it was often glancing or slighting, or was mostly about Grey as a bestseller phenomenon, rather than about his individual merits.

And there's a reason for this. It's because the most popular Western-fiction writers (Grey, Brand, Short, and L'Amour) tended to write a lot of novels, often upwards of 100 novels, and usually there wasn't much to differentiate them from each other. Moreover, although each novelist had a few books that deviated from their own formula, they all wrote books that don't necessarily feel that distinctive. L'Amour's most famous novel, Hondo, feels like it could've been written by Grey, Brand, or Short.

This isn't a knock on those writers: what they did was extremely valuable and good. Zane Grey, in particular, was an innovator. He developed this tremendously fruitful formula. And all of these writers used their talents to make a lot of money—in some cases (Brand), that's all they cared about. They told themselves they were just writing for the money. In other cases (L'Amour) it's clear they desired a literary respectability that never truly came.

There was a path to respectability for a genre Western writer. But in order to achieve it, you needed to slow down a bit and to play around with the formula somewhat. And, not only that, you needed to break into the slicks.

The two traditions met in the slicks

The real path to respectability for a genre Western writer was to publish in the slicks. This is a category of mass journal that had circulations in the millions and which published a variety of fiction. Some of the slicks (Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post, in particular) published a lot of adventure fiction.

As part of my reading of Westerns, I read a volume from the Library of America called Western Novels of the 1940s and 1950s. And out of the novels in this book, three of them (Warlock, The Ox Bow Incident, and The Searchers) were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post. Another, Shane, was serialized in another slick. In fact, many of the most famous literary Westerns from the slick era originally appeared in the Post.

The Post was the perfect place to serialize a Western, because readers of the Post were familiar with the tropes of the Western, but they weren't wedded to them. They read the Post precisely because they wanted to read a larger variety of things, and they wanted to read things that challenged them. Although today the Post is considered passe and middlebrow—that's not necessarily how its own readers viewed it. They didn't necessarily consider it to be inferior. They felt like they were reading smart stuff.

And they were right! These novels that were originally printed in the Post—and the writers who flourished there—seem, to me, to be distinctly more interesting than the writers who primarily published in the pulps.

And I am not alone in thinking that. The Western Writers of America—an association of Western-fiction writers—released a list in 2021 of the best Western novels of all time. Their list of twenty-five novels has no dime westerns, no novels originally serialized in the pulps, and only two paperback originals. All of their entries were either printed originally in the slicks or were hardcover-originals.

As a sidenote, when I write about the Westerns, I am going to use the term 'genre Western' to refer to novels written for dime / pulp / paperback original publication and 'mainstream Western' to refer to novels that first appeared in the slicks or were published straight to hardback.

The genre Western has made no direct footprint on literature

There is something kind of depressing about this story. Between dime novels, pulp journals, and paperback original lines, there was a vast amount of Western fiction that was produced for this Western-fiction audience. And not a single writer who wrote primarily in these venues has really achieved any kind of critical respect. Maybe the sole exception is Elmore Leonard, whose first few novels were Westerns writing for paperback original lines, but his reputation really arises from his crime novels, not his Westerns.

However, I do think that the genre Western was valuable. First of all, I've read a number of genre Westerns now by Brand, Short, and L'Amour, and they're good. This core story, they tell, about a man who is tested by the elements, and who is tempted by evil, but who chooses good—who puts his life on the life to protect what is good—that is a great and inspiring story.

That's the thing about the West. These people, these gunmen and cowboys, they often didn't have exceptional abilities. They were just men. They carried guns, because everyone carried guns. They grew tough because of their circumstances, not because they were essentially tough. In some ways, these stories have the same appeal as post-apocalyptic fiction. They make you think...well...maybe if I faced exceptional circumstances then I too would find a way to rise to the occasion.

My favorite mainstream Westerns are the ones that use mythic tropes

Moreover, this core Western story, which was developed and upheld by these men—it became extremely influential in our society, to the point where virtually every literary Western was forced to comment upon it or play with these tropes—the lawless frontier, the woman in peril, the harshness of the elements, the lone gunman who upholds what is right. The genre Western is really what drove interest in these tropes.

In fact, genre Westerns and the mythic Western are so closely-related that I am tempted to use the two terms interchangeably. But I don’t do so, because there are definitely some mainstream Westerns that also used mythic Western tropes.

This Library of America volume only contains mainstream Westerns, but the two books that I enjoyed most were the ones that were the most respectful of the mythic Western tradition. Shane was the first work of fiction by Jack Schaeffer. It was originally serialized in a slick and then had a hardback release. The Searchers was by a writer, Alan Le May, who had written for the western pulps, but who transitioned to writing for the slicks—The Searchers was originally serialized in The Saturday Evening Post.

Neither of these books were breakout bestsellers when they were first released in hardcover, but they sold respectably. Today, they are best-known because they were the basis for two movies that are amongst the most highly-acclaimed and best-remembered Westerns that Hollywood ever made.

Both of these books served their authors' purposes. These writers were both primarily authors of Westerns. They wrote other books that were well-received and were often adapted for the screens. Since their deaths, these books have had a spotty publication history—most of Schaefer's work is out of print, but Shane has been kept in print by UNM press. The Searchers was out of print for a while, but was reissued in the 21st century by Kensington Books, whose Pinnacle imprint has the last remaining dedicated Western line at a decent-sized press.

Both of these books are well-known amongst lovers of Western-fiction. If you enjoy this type of fiction, then you probably think Shane and The Searchers are amongst the best examples of it—Shane in particular appears on almost every list of best Western-fiction novels. However, the number of people who even care enough to peruse such a list…well, that number is unfortunately dwindling every year. As a result, Shane and The Searcher need to either make the jump into the regular canon—the jump made long ago by Blood Meridian and Lonesome Dove—or they'll be forgotten entirely.

Shane is a perfect novel

Of these two books, the best is Shane (1949). This novel is absolutely perfect. It is very short, almost 40,000 words. And yet it proceeds at a deceptively quiet pace. For starters, the book is narrated by a man, Bob Starrett, who is remembering events from his youth. He tells us about something that happened when he was six years old. A stranger came to Bob's home, an isolated farm in Wyoming.

This stranger, Shane, is immediately charismatic, magnetic. Bob's father, Joe, really takes to the stranger, and they spend several chapters trying to get rid of an old stump in the yard:

[My father] picked a root on the opposite side from Shane. He was not angry the way he usually was when he confronted one of those roots. There was a kind of serene and contented look on his face. He whirled that big axe as if it was only a kid’s tool. The striking blade sank in maybe a whole half-inch. At the sound Shane straightened on his side. Their eyes met over the top of the stump and held and neither one of them said a word. Then they swung up their axes and both of them said plenty to that old stump.

The dad invites Shane to stick around the farm. And although the narrator doesn't say it outright, because he doesn't understand everything that's happening, we as the reader know that Shane is tough, and that the father wants him around the father is being menaced by a local rancher, Fletcher, who wants the father's land.

However, Shane has a mysterious past. There's something about him that's sad and haunted. The boy notices that, unlike everyone else in the West, Shane doesn't wear a gun. But the boy's father advises him not to ask Shane about it:

There are some things you don’t ask a man. Not if you respect him. He’s entitled to stake his claim to what he considers private to himself alone. But you can take my word for it, Bob, that when a man like Shane doesn’t want to tote a gun you can bet your shirt, buttons and all, he’s got a mighty good reason.

The tension builds and builds. We come to realize that the narrator's mother has fallen for Shane, though of course she won't do anything about it because she's too honorable. Meanwhile one of the other local farmers is killed by a gunman hired by the evil rancher. The father, Joe, prepares to confront the rancher. Despite the short length of the novel, everything builds very slowly. There's a whole sequence where Shane refuses to get into a fight with some toughs employed by the rancher, and the town castigates Shane as a coward.

Eventually, of course, Shane picks up a gun and rides to the rescue of this family. And you can tell he's doing it because he sees something honorable in this father. That he, Shane, wishes he could've had a father like Frank and a home like the one Frank has given to his son. We see that although Shane had sworn he would never kill again, he realizes that in this case he needs to.

It is so haunting, so sad, because there's such a sense of loss. In order to defend this household, Shane loses a part of himself. And as a result, he's no longer fit to stay with them, so he chooses to ride on (there's also a suggestion that Shane has received a mortal wound in the final battle and is riding onwards to die quietly).

The narration concludes:

He was the man who rode into our little valley out of the heart of the great glowing West and when his work was done rode back whence he had come and he was Shane.

This book is so good. It is wildly good. It is amazing! It was such a pleasure to read this novel, and I have no hesitation in saying it's the best out of the fifteen Westerns I’ve recently read.1

Shane is clearly working within the parameters established by Zane Grey, but there is something so simple and so taut about the book that it really feels like this novel is the absolute perfect, best example of this kind of fiction.

I think a lot of the magic comes from two things: first, the point of view of this kid, who sees Shane with a child's eyes. And second, the character of the dad, Joe Starrett, who is a brave and good man, but who isn't a gunslinger like Shane. That's the whole point of the book—if it was just Joe out there, facing the ranchers, then he would be dead. The magic of the book comes from that transference: we can see ourselves in Joe and his son, and we can imagine being respected and befriended by a man like Shane.

The Searchers is also very good

This 1954 novel is about two guys in Texas who spend five years searching for a girl who's been kidnapped by Comanches. The striking, affecting quality of the book comes from the vast span of time and distance that it covers. They wander out on the trail of this band, and before you know it, years have passed. They learn how to speak Comanche. They become traders of trinkets and goods. They cross into Mexico. They participate in raids and skirmishes. They are absolutely indomitable.

But at the same time, the younger man, Martin, starts to worry that his companion, Amos, doesn't really care about finding this girl, that he's just addicted to the idea of revenge. And there's the implication that in this search they've become brutalized and unhuman. That by dedicated themselves to this idea of civilization and womanhood, they have themselves become uncivilized, and Martin, at least, has forgone his chances at a family of his own. There’s a sense of loss, a sense that the West has destroyed these men, and, moreover, this destruction was good and necessary, because it's only by becoming hard that they're able to protect other people.

But because Shane is so much better, I won't describe The Searchers at length.

The Saturday Evening Post also serialized my least favorite Westerns

Shane and The Searchers are a kind of book that is extremely hard to find: the taut, well-crafted action thriller. It's very rare, in my experience, to find a book that uses the tools of adventure fiction and turns them up to eleven, delivering a story that is combines taut pacing, high emotional stakes, and thematic depth. Instead, many action thrillers, especially when they're written by genre writers who work at a fast pace, often seem somewhat baggy and overwritten, and this is the problem with many of the genre Westerns that I read—Max Brand, in particular, has inventive plots, great characters, and a way with language, but his books are just too long for their content, and the energy tends to leak out.

But, on the other side of the coin, when mainstream writers attempt an action novel, their books also tend to be over-long and boring, because the novelists are so focused on adding moral complexity that they forget to write characters who feel real and have genuine emotional stakes.

It was impossible for me to avoid these negative thoughts about mainstream Westerns because this volume, this Library of America compendium, also included two other Westerns. And these two Westerns were quite different from Shane and The Searchers. These two Westerns, Warlock and The Ox Bow Incident, were also serialized in the Saturday Evening Post. They were also the basis for films. Their authors also primarily wrote Western fictions.

These two books are somewhat more famous, as books, than The Searchers and Shane. Warlock was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1958. It was out of print for a while in the late 20th century, but it was reissued by the NYRB Classics since 2005 and has seen steadily popularity since (one of my book clubs selected and read it six years ago). The Ox Bow Incident is even more popular. It's never gone out of print and is available nowadays as a Modern Library Classic. It was recommended to me by four people when I asked online for a list of best Western fictions.

Warlock was written by Oakley Hall, who got an MFA from Iowa, and taught for a number of years in various MFA programs, including at UC-Irvine. Walt Clark, the author of The Ox Bow Incident, was also a professor of creative writing for many years at the University of Montana.

Of these two novels, the better one is The Ox Bow Incident. In this novel, a cowboy is killed by cattle rustlers, and in response a group of men get together and ride off to bring the killers to justice. They catch up to some guys in a mountain pass, and they hang them. The novel is well-written and intriguing. It does a good job of portraying the mob mentality—the way that nobody in this group really wants to be out here, doing this, but they all feel pressured into it. The book is quite clearly a response to the vividly-described lynching sequence in Owen Wister's The Virginian. Walt Clark’s novel is a good book, it definitely deserves to be read and remembered.

I had a harder time with Warlock. This book is a fictionalized account of Wyatt Earp's career in Tombstone, Arizona. It's about a town that's being terrorized by a gang of cattle rustlers and ne'er'do'wells. So the merchants of the town pool their money to hire a gunfighter of their own, Clay Blaisdell. But on occasion he goes too far, kills people he shouldn't. He's also taken advantage of. The merchants try to use him to end a strike at the mines, and his friend Morgan uses him to settle personal scores. And his presence in town sets off a cycle of violence that, while it creates a feeling of control, probably results in more death and mayhem than there would've been if he hadn't been there.

The problem with Warlock is that it's told at extreme length, from a number of viewpoint characters, and it feels like there's a lot of repetition: an endless succession of petty disputes and maneuvers. It's a book with a lot of vision, but not enough craft. It really could've used some of the art that pulp writers use to make their books interesting and to hook the readers. I respected the book, I suppose, but I did feel a little offended that the author did so little to make the book interesting and move the action along.

Both books, The Ox Bow Incident and Warlock, seem uninterested in the basic techniques of fiction, where you create some kind of stakes, so the writer can get invested in these characters. There is a core conflict that is so apparent in Shane and The Seachers, where you can feel the struggle within these characters between what they desire for their own lives and what they feel to be necessary for the community—whereas the core conflict feels very muted in The Ox Bow Incident and Warlock.

I don't think writing programs are the problem here

The experience of reading this volume and having very different reactions to these two books—it really made me want to come up with some kind of theory. Why is it that the two more-famous, more-critically-acclaimed books were so much worse than the two less-famous books?

I was tempted to blame writing programs somehow, but in attempting to come up with this theory, I realized that there's nothing I could say that would be truly convincing. Yes, it's true that Oakley Hall and Walt Clark were associated with creative writing programs, and that their work does seem a bit writerly. Their books are really stories that are about other stories. They are deconstructing other stories, and the interest in their books comes from the way they up-end the reader's expectation. That's also why the books aren't good, because they also eschew expectations that are useful, like the expectation that the reader be somewhat invested in the characters and the underlying situation.

But as I started to think about it, I realized that the authors of Shane and The Searcher were really writing at the end of of one tradition—the mythic Western. And as a result, they had better control of their material and a better understanding of how to produce a mythic Western that was complex and argued against itself, while still being satisfying,

However Oakley Hall and Walt Clark were writing at the beginning of a different tradition, the revisionist Western. And this tradition would really need a few decades to come to fruition. I would say that the mistakes made by these books are what influenced later writers to make different decisions. Both Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry have a much better understanding of which storytelling expectations are useful in driving a reader's interest and which ones they wants to play around with. As a result, they create stories that are just as engaging as those of the mythic Western, but are able to situate them in a much more complex, ambiguous moral universe.

However, this post isn't about those McMurtry and McCarthy, because although their books are very good, their revisionist project means their books fail to capture a lot that is good in the mythic Western tradition.

The good man with a gun

There is a reason that I have spent a month reading these books. It's because I really responded to this story they tell, about these heroic gunmen. It's very similar to the kinds of stories that inspired me as youth.

You know...here on Substack there is a lot of talk about the New Romanticism: an aesthetic movement that seeks to turn away from some mechanized or empirical view of reality, and to return to some vision of individual greatness.

And it seems to me that here in the Western genre, we really have an encounter between two artistic tendencies: romanticism and realism. The Western genre was created from the raw material of these romantic myths about the West. Zane Grey didn't create those myths. Neither did Owen Wister. Those myths were circulating in newspaper articles and travelogues and tall tales long before anyone wrote stories about them. Even in James Fenimore Cooper, we see a lot of these same myths, about good-hearted frontier nobility and its flipside, lawlessness and evil.

And there is a cadre of Western authors (Grey, Short, Brand, L'Amour) who embraced the myth and made a lot of money doing it, but whose work seems to lack the kind of individual stamp that renders a book timeless. There's another cadre of Western authors (Oakley Hall and Walt Clark) who mostly embraced realism, and got respect, but weren’t necessarily able to inspire strong emotions in the reader. And then there's writers who mixed realism and romanticism to varying degrees, and these writers are the ones who really created some kind of magic.

We can argue, for each individual writer, about how much realism and how much romanticism is in their books, but it does seem like that mixture is really what produces a book that can speak not just to the present moment, but to a broad range of times.

Personally, I think that in our highbrow literary culture, we celebrate realism a bit too much. Probably that's simply because in popular culture, it's the opposite, it's romanticism that gets celebrated. The Western is done, yes, but we're now in a twenty-year run of these superhero films that are basically the same as Westerns: they're about powerful men who are good at heart and take the law into their own hands.

And of course I am gonna get in trouble just for saying 'highbrow culture celebrates realism', because, as Lincoln Michel noted in a recent post, the world of literary fiction has actually become a lot more friendly to genre influences in the last twenty years.

But...I will say that I have been dissatisfied with a lot of literary fiction that uses the tropes of genre fiction, because its treatment of those tropes often seems somewhat condescending or careless. For instance, last year I critiqued Rachel Kushner's Creation Lake for writing a spy thriller that 'subverted' the genre by...being boring and not very thrilling. Similarly, there are literary science fiction novels like Station Eleven that are celebrated for inject some realism into sci-fi scenarios, but which leave out the heroic, larger-than-life quality that makes those scenarios compelling in the first place.

There is a lot of highbrow literature that seeks to interrogate popular tastes or hold it up to critique—the same way the Ox Bow Incident seeks to interrogate the lynch mob in Owen Wister's The Virginian—and the maneuver is often praised as a brave deconstruction, but ultimately it's very easy. It's easy to say (as I tried to for years) that an ordinary person, if they were sucked into a fantasy world, would die. We all know that.

What's harder is to do what Alan Le May and Jack Schaeffer did, and to take what is good in popular culture and to render it down to its essential elements, turning it into a timeless object that can be appreciated even by people who aren’t steeped in the culture from which that work arose.

In the case of these two authors, they are beginning to get their just desserts. Their inclusion in this Library of America volume is a great start, and I have high hopes that it means their books will be read more frequently in the decades to come.

Genius is an illusion

One thing that sometimes troubles me about the literary culture on Substack is that it’s so wedded to the concept of genius. I first encountered this on John Pistelli's blog. He often says "it's lonely at the top". He argues that the best writers really are that much better than everyone else. That literature is a competition to become that one singular genius who is so relentlessly unique that they outlast everyone else.

Ross Barkan wrote similar sentiments. A great book is a result of:

…that lone ranger, the author, digging in for long days and nights, groping toward beauty. It’s up to the author to care anda believe in it. If you aren’t trying to write a great book, one that crackles with genius, what’s the point?

Personally I am also somewhat invested in the notion of genius. After all, genius butters my bread. Some of the Great Books (the Bible, the Mahabharata) are by collective authors. With others (The Iliad and the Odyssey), there is a debate about whether there was collective or singular authorship. But most of these books are by singular authors who essentially define what it means to be a genius. If literary genius means anything, then it means Herman Melville, Franz Kafka, Marcel Proust, Shakespeare, Chaucer—writers who seem startlingly fresh and outside their own time.

And this story about genius is a very convenient way to understand literature. Each age produces a few singular geniuses, and these geniuses embody whatever is best in that literary era. Oftentimes, these geniuses were not particularly popular in their own era, but they still seem to be very much in touch with the spirit of their time, in a way that makes that era legible to us now, in the future.

Moreover, many writers have themselves understood genius in this same way. So we know that Larry McMurtry looked to the great 19th-century realists (Flaubert, Tolstoy, Eliot) as models and saw himself as writing in their tradition. This means that the story of literature as a succession of geniuses has a lot of explanatory value: if we perceive literature as a set of geniuses building upon each others' work, then we're not wrong.

But...this story also misses something.

For one thing, there are entire literary traditions that are not captured by our story about genius.

Earlier this year, I spent four months writing about 19th-century American literature: it was all Twain, Hawthorne, Poe, Melville, all the time. But while I was writing that stuff I got very interested in fiction that was popular in its time but has subsequently been forgotten, and I wrote several posts about James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and the sentimental novelists.

These novelists trace a very coherent Romantic tradition—they wrote about big emotions, larger-than-life heroes, and they often had an explicitly Christian worldview—in a way that really does not seem captured or represented by our typical story about American literature.

Similarly, this whole tradition of Western fiction is represented right now by these revisionist writers, Larry McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy (and Charles Portis, with True Grit) that seem to leave out a lot of what made the Western so compelling.

Moreover, even if we regard these writers as singular geniuses whose work is able to stand in for a whole tradition, this really misses the fact that they could not have written these stories if they hadn't had that mythic Western tradition to write against. That the mythic Western is the piece of grit around which they formed the pearl.

If genius exists, I don’t think it’s a matter of individual talent. Works of genius only appear once a given tradition has reached its maturity—it's only once a lot of other people have done a lot of work, to develop certain themes and techniques, that all this stuff can be brought together in the work of genius. The art of film-making, before it could produce a work like John Ford's movie, The Searchers, needed the material provided by the book. And that book needed the material that was developed by Zane Grey, and Zane Grey needed all the stories from the dime Westerns. All of this built on itself, over time, before The Searchers, one of the greatest films of all time, could even come into existence. And with every work of genius, it's the same—it relies on a lot of other literary activity that we, as the reader, don't necessarily know about.

I do think there is a purpose that is served by various forms of writing that are considered subliterary. On this website, on Substack, I see people railing all the time against romantasy or YA or whatever else they think is popular, sentimental dreck. But those are exactly the same complaints that people leveled against dime Westerns and pulp fiction, and yet it's clear, at least to me, that the dime Western and the pulp Western created the milieu from which great books and great films arose.

This deep, basic mythic stuff, whether it is romantasy or the genre Western, operates on very powerful emotions. And there is something valuable in creating the images and scenes and archetypes that stir up those emotions. And in some ways that work is very collaborative, so you can't necessarily say, "Who first thought of the idea of the lone gunman who rescues women from peril?" That's an idea without an inventor. But I can see that Zane Grey was taking a lot of techniques from popular adventure-pulps like Argosy, and he was applying them to pre-existing Western tropes and settings. And I can see that this union was tremendously powerful and fruitful.

In my own work, as a newsletter writer, I can see the ways I am influenced by other people. For instance, my technique of re-evaluating 20th-century writers is heavily influenced by Henry Begler. My way of writing headlines is drawn from Slate and Buzzfeed clickbait articles. My style of breezy narrative summary is influenced by Celine Nguyen.

And of course I have my own stuff that I add to the mix—for instance, when I investigate niche topics like the Western, I always try and draw the story back to contemporary controversies about art and artistic creation, because that's a hook for making people care about this stuff. And I'm sure someone else out there will copy that technique of mine and do their own thing with it.

Personally, I've grown and improved tremendously because I'm part of a community of people who are doing similar things. That, to me, is really what's happening in all these pulp and popular-fiction genres. You have a lot of people making tiny refinements.

And, yeah, someone at some point puts it all together, and they get rich, like L'amour did. While other people figure out ways of taking that knowledge and pitching it to a more sophisticated audience, like Jack Schaefer and Alan Le May did. And some people learn how to please the core audience really well, like Max Brand did. Some people critique or subvert these techniques like Walt Clark and Oakley Hall did. Some people are overpraised for minor innovations, while other people's contributions are lost to history.

But in the end, whatever each person does—it matters. Even if you only contributed a little bit, and even if nobody remembers, it still matters. It is still recorded somewhere. That's what literature is, the record of all those ideas and improvements. And that record is often folded into the work of a few big names, who get acclaimed as geniuses. And that's right and good, because it ensures that their work gets read, but it also obscures the fact that when you're reading McMurtry and McCarthy you're also reading Zane Grey and Lytton and Owen Wister and Max Brand and the work of hundreds of other people. They're all in there, right alongside the geniuses, and those geniuses could not have existed without the efforts of these now-forgotten writers who worked to hone and upheld these myths.

P.S. Earlier this year, I made a list of the best reprint publishers, and I kinda talked trash on Library of America, but I really need to retract those statements now. Library of America is excellent! Their books were at the core of my recent investigations into Raymond Carver, O. Henry, and, now, the Western. If you’re looking into Westerns, you could do a lot worse than buying their compendium, The Western: Four Classic Novels of the 1940s and 50s. It’s a great book, a perfect balance of mythic and revisionist tendencies.

In order to write this post, I read the following Westerns, in the following order:

Zane Grey, Riders of the Purple Sage (1912)

Owen Wister, The Virginian (1902)

Edward Lytton Wheeler, Deadwood Dick, Prince of the Road (1877)

Walter Clark, The Ox-Bow Incident (1940)

Oakley Hall, Warlock (1958)

Alan Le May, The Searchers (1954)

Jack Schaeffer, Shane (1949)

Max Brand, Destry Rides Again (1930)

Max Brand, The Untamed (1919)

Larry McMurtry, Lonesome Dove (1985)

Louis L’Amour, Hondo (1953)

Larry McMurtry, Streets of Laredo (1993)

Louis L'Amour, Flint (1960)

Louis L'Amour, The Sackett Brand (1965)

Louis L'Amour, Conagher (1969)

I’d previously read True Grit and Blood Meridian, but didn’t re-read them for this post.

Perhaps interesting to note that of the endless parade of superhero films, the one probably most acclaimed—Logan—not only riffs on elements from Shane but directly cites the film version of Shane.

You're really doing a unique service by bringing these literary genres into the popular (well, insofar as Substack is popular) consciousness. Thank you! (And this post led to me finding what appears to be a Tanith Lee space western, so thank you again.)