A Dilemma

Erdric had never heard of slavery.

"It's very similar to serfdom," Andras said. "You have serfs in your village, no? Some of the farmers—they owe customary duties to their lord."

"But that is no different from a rent. That is not forced."

"They are required to give it," Andras said. "And are bound to the land, unable to move. If they leave, they can be hunted down and taken back."

"Why would they leave their land? It is their land. You don't leave land, you keep it."

This was somewhat absurd of Erdric to say, since he himself was an eldest son who had left behind his father's land, but the Paladin could be inconsistent sometimes.

Anyway, the concept of slavery made no sense to Erdric. To keep someone chained up, to force them, through violence, to work for you. It was wrong. He had never heard of such a thing. It was what ogres did in stories—human beings didn't do such things.

But it was necessary to make Erdric understand that slavery was, in fact, permissible in their kingdom, because Erdric had recently heard about a terrible crime: a Marcher lord, one of the little knights who lived on the border of recently-conquered pagan lands, was taking pagan women captive and doing things to them.

Everyone in this region was familiar with this lord, Damien, and with his women. Even Andras knew about them. This lord had a chamber in his home—his seraglio—where these women were kept, and he invited his knights to participate in the things he did to them.

"The women are said to be quite willing," Andras said. "They were trained in these things—the women—it is what they know."

But Erdric was not convinced. He set his course, walking to the castle of this lord. He intended to kill the man.

Normally, the Paladin and Ser Andras slept outside, and they ate only their special bread. But Erdric had also learned to recognize homes that kept to the old ways: their lintels often sported special runes. And in these homes, he could often rest and get his food.

However, in one village, Andras insisted that they linger for a while in a different home. It was a bad home, poorly kept, where the straw was rotten, and the children shivered in a corner, far away from the coals.

Erdric did not want to stay in this place, where the woman was silent, where the children were sullen and did not play. In the morning, Erdric stopped for a moment by a source of running water, and he scrubbed his hands and face, trying to wash the evil away.

"That man was a bad man, no?" Ser Andras said.

Erdric remained silent.

As they walked, his companion kept harping on the subject. "That father, that husband, that man in the hut—he was bad. And in your own village, you knew men just as bad. But you did nothing."

"Women do not want their men to be harmed. If she had somewhere else to go—some family, someone to protect her—then she would be with them."

"And it is the same with these pagan women. They have nowhere else to go. With Damien, they are fed, taken care of. It is their lot in life."

"But it is wrong."

"Why is this wrong? Ser Damien, he is a great knight, a great lord. He has pushed back the frontier by twenty miles in his lifetime. The pagans treat equally with him in a way they never did with his father, with any other lord. He has brought peace and prosperity. And what will you do?"

The argument continued as they walked. Erdric’s friend believed that in this world some had been decreed by God to rule and some to serve. And that rulers were the ones who had the deepest moral burden, because it was their responsibility to rule well, which was difficult. Sir Andras said that the bulk of people—those destined to serve—did not understand the difficult cup from which the rulers drank, the terrible responsibility that came with their position.

This was the religion that Andras had been taught. For a time, his family had intended him for the priesthood, so Andras was better-educated than most of his class, and he knew many complex arguments about the religion of the so-called “One God”.

But Erdric did not belong to this particular religion. He had never belonged to it. Growing up, he had worshipped the local saints, whose spirits dwelt in holy places: streams, caves, and crossroads. But Denrickson, his mentor, had explained to him that these saints were just another name for the ancient gods of the common-folk. That, in worshipping these saints, he was worshipping something quite different from the “One God” of the nobles.

The Paladin had stopped worshipping the saints, but he did not worship the god of the nobility either. Instead, Denrickson had taught him to worship Rightness itself—the all-pervading force that governed the entirety of existence.

Personally, the Paladin did not have strong beliefs about the nature of the universe or cosmology or all that stuff. He worshipped rightness, and that was enough. He knew what was right, and he obeyed it. He derived his power from certain practices: not eating meat, retaining his semen, and eschewing intimate knowledge of women. And these practices could give anyone power. You didn't need to know how they worked, because they did—everyone knew they did.

Damien's castle was large, and it was getting larger—a team of workmen had come from some distant shore, lured here by Damien's gold. They spoke in their own tongue and ate their spicy food. There was also a caravan—many carts hitched in the courtyard—much swapping of goods. Erdric saw an animal with a long neck and soulful, sad eyes. Damien was known to love strange beasts. And inside the hall, indeed, they were three large colorful birds.

When they reached the abode of this lord, they were welcomed, given food and drink, and a chamber of their own. Andras was a knight, after all, and his family was known to Damien.

At dinner they sat far from the lord, and Andras was subtly mocked for his lack of valor. One knight in particular, Ser Galwin, had a particular way of making merry at the expense of Ser Andras, and the Paladin was somewhat amused by the raillery, because he was tired of Ser Andras's vanity.

The way Ser Galwin mocked Ser Andras was by saying, "Have you come to take service with our lord? Come to fight in the wars?"

"I'm afraid that I remain a tournament knight," Ser Andras said.

"Never fought in one," Ser Galwin said. "I have heard sometimes men die."

"Regrettably," Ser Andras said.

"The clash of lance against lance," Ser Galwin said. "It is like nothing that the wars can offer. We fight against the pagan. For them, it is a mere shower of arrows, and then they fly. There is no straightforward combat."

"All of your life collapses to that point," Ser Andras said. "The point of the enemy lance. And after you've broken one, it does not end. They come and come until someone is unhorsed."

"Tell me, is it true, you broke twelve lances against the Lady's Girdle?" This was apparently the name of a famous knight.

The rest of the table was composed of men who had faced battle, faced death. But they were smiling and appreciative, and they urged Ser Andras to speak at length about his tournament bouts. They were mocking him, which Ser Andras didn't seem to recognize.

Thankfully, they tired soon of this sport, and they turned their attention elsewhere. The castle was host to a visitor: a dignitary from the interior of the kingdom.

Pointing to the stranger on the dais, Set Andras said, "That man, Theodoric, is one of the King's closest advisors."

"But who is he?" Ser Galwin said. "You do not call him ser."

"He is not a knight, but his family—"

"I do not care about his family," Ser Galwin said. "But I want to know...where is he from?"

Ser Andras seemed puzzled. "I must confess, I don't understand."

"If this Theodoric is not a knight, then whose man is he? Who does he serve?"

"He serves his own interests..." Ser Andras said. "He has certain trading concessions with the courts. And he owns considerable land."

"And where is this land?"

"All over the kingdom, but largely near the capital."

Ser Galwin frowned. He did not understand. Neither did Erdric. Ser Andras had tried to explain to him that there was a new class of men in this kingdom, and they had power that arose neither from birth nor from martial valor, but the concept made no sense to Erdric. If these new men were not strong or well-born, then the moment they tried to dominate better men, they would be killed. No amount of wealth could protect someone from a slash to the throat. But Ser Andras claimed that somehow it did.

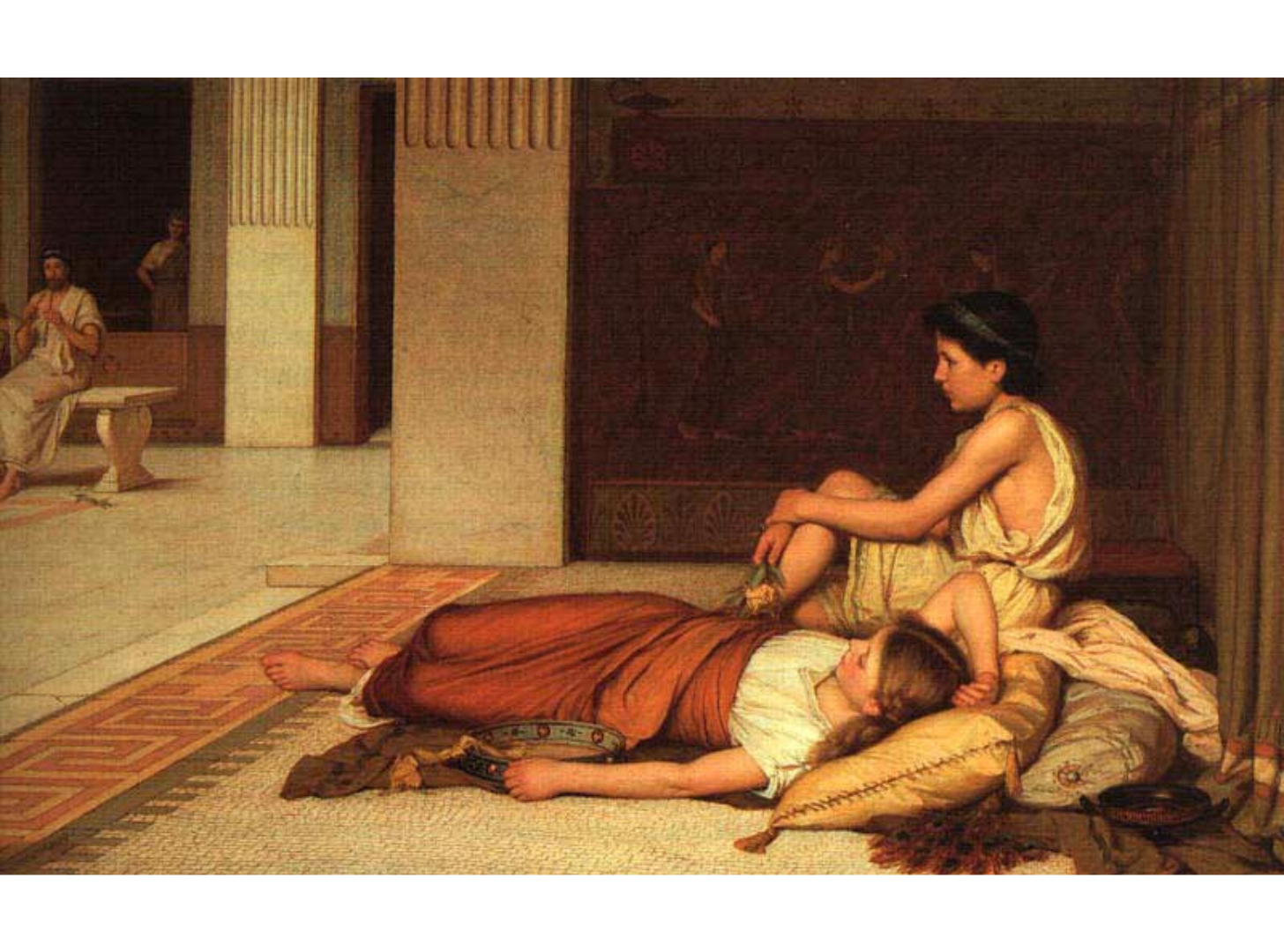

Up at the table, they saw this man, Theodoric, in his robes, and he was laughing and chortling with Damien. And these two men were in the prime of life: large, broad-shouldered, running to fat—powerful men. Damien himself had an air of easy command, easy deference. But it would be a lie to say that any attention was on them. The attention instead was on the women: five of them, who were attired in silk that showed most of their body. They were very young, smooth-skinned, somewhat dark, with flowing hair and large eyes. They were like nothing Erdric had ever seen before. They seemed more like nymphs than human women. And they were hanging over these two men, caressing them, fawning them, and the men's hands cupped the women with an air of possession.

And everyone in this hall, although they were diverted and titillated by the display, seemed to accept it as a natural thing.

"Who are these women?" Erdric said.

"His playthings," Ser Galwin said. "His harem. His seraglio. He found them on our last campaign. Rescued them. But it's the only life they know. Previously they served some pagan lord."

"Where do they live?"

"There are apartments in the castle."

"I do not believe this tale," Erdric said.

"It's true," Ser Galwin said. "What is there not to believe?"

"I believe that he brought these women home from a campaign. But I think he killed their fathers, killed their husbands, and that he is holding them against their will."

Ser Galwin smiled. "This is war. We are finally winning it. They've taken our kind for decades—for centuries—and now we're pushing them back. Doing the same as they've done to us."

"So you admit it."

"They have always done it," Sir Andras said. "These Marcher lords have always taken captives from raids and sold them to other pagans up north. I have told you, Erdric. This is the custom in these lands. Not often practiced, yes, but allowable."

"It is wrong."

"How is it wrong?" Ser Andras said. "You cannot explain. It is the legitimate spoils of war."

"It is wrong," Erdric said. And he repeated the words, speaking not to Sir Galwin and not to Sir Andras, but to this entire table of knights. "You are sworn to protect women's chastity. These women have no husbands. What we are witnessing is wrong."

"And what'll anyone do?" said one of the knights, an older man. "Nothing."

"God will judge this behavior," Erdric said. "You will weaken. You will fall. You will lose in war. This behavior will destroy you. Everything you have in this hall—it will be destroyed by this behavior."

"How?"

"Because justice prevails," Erdric said.

"Easy words," the knight said. "Go and stop it then, if justice prevails."

And Erdric looked at the men on the dais, at Damien and Theodoric. They were two of the most powerful men in the kingdom. This castle belonged to them. All of these knights served them.

The Paladin had no doubt that he could kill Damien. He did not fear this man, this Damien, who was reputedly a famous war-leader. Erdric had met many of these men already in his life—these noblemen who were so used to deference and command. And Erdric knew nothing of war, but from what Andras had told him, in war you were surrounded by other men who protected you. And if you survived the experience, and your side won, then you were accounted brave and good. Erdric knew nothing about that—perhaps there was some particular skill in war that this man possessed. But Erdric knew about struggle with arms, and he knew that in any combat, on any terms, he could beat this Damien.

But then what? Look at these men—they hungered for these girls. If Damien was dead, these men would hurt these girls. They would have their way with them, and ultimately the girls would suffer horrible deaths. The Paladin knew this to be true. So, as bad as Damien was, his existence protected the girls to some extent.

That night, the Paladin told Ser Andras to stay in their chamber, no matter what happened.

"Why?" Ser Andras said.

"Because that knight, Ser Galwin, he will come with several of his men to kill me," Erdric said.

"But...why?"

"I do not know."

"Will...will someone be paying them?"

"No."

The Paladin could just tell. He could tell it in Ser Galwin's manner. That they would come looking for him in these hallways, and they would beat him, and they would kill him. Because this castle was lawless. When the lord considered himself above the law, then he had no ability to enforce it on others.

So that night the Paladin went out into the halls. He knew his sword would be useless in these close quarters, but he took two knives. And he waited there, standing, for several hours. And then he saw Sir Galwin, drunk, and a crowd of other knights—five in total.

"You," Sir Galwin said. "You spoke roughly to a knight."

"I did not," Erdric said. "I exhorted you to remember your oaths."

"You impugned our honor."

"Yes," Erdric said. "I impugned it. The behavior in this hall is foul. It will be punished by God."

These knights had come with clubs, but weren't used to being toughs. This environment in this castle was new as well to them. They had grown up in good families, trained in the knightly arts. In their homes, people might fight with fists, but they didn't assemble in mobs to murder people. And Erdric knew that if he had wanted, he could have talked them down, convinced them to turn away.

But instead he hid the knife in the fold of his cloak, and when they approached, he stabbed Sir Galwin in heart. Then he wrenched the club from Sir Galwin's dying hand, and he leapt upon one of the other toughs, hitting his head. The others ran, but Erdric chased them. He stabbed one in the back, and then he leapt upon a fourth, battering his head against the wall. One made it further, running blindly in these halls, and the Paladin thought he had lost him, but he came across a servant woman, who subtly gestured with her eyes. And the Paladin followed her her lead, chased the man down and beat him until he was dead.

This hall contained perhaps forty armed men. Erdric had killed five of them. And in this hall, there was fear. Nobody went out into the halls to see what he had done.

Now it was Damien's turn to do something. He had a dignitary in his halls, Theodoric. He needed to stop this menace, or the King would hear that Damien was weak. So the lord summoned the knights in his service, and he conferred with them. But he did not know what was happening outside, nobody did. His servants, who ordinarily would have come and informed him of Erdric's movements, because this castle was their home—they did not come to him.

Instead Erdric had simply disappeared. And what could Damien do? He put two men outside Ser Andras's room as a guard. He had a household guard, Sir Odric, a trusty knight who had served him in many wars, and Sir Odric had sworn to hunt down and kill the Paladin. So Damien waited in his rooms. And because he was bored, he ordered for the presence of his women.

There were five women now, but once there'd been more. They knew what he did to women who displeased him, so they did not complain. Damien did not see himself as bad. He was just doing what all men would do if they had enough power. He'd gone to war, and things happened on campaign—things everyone knew about. So why shouldn't they happen at home? Instead of selling these girls onwards to the Northlanders who put in sometimes at little coves, Damien decided to keep them instead, as the spoils of war.

But he did not realize that very few men would actually want the kind of relationship that he had with these women. That yes, he could goad his men into participating in these rites, but it was a shameful thing, and many of these men told themselves that the women participated willingly, or that they were a different kind of woman, who wanted such things. Few men were willing to confront the truth of what they were actually doing.

Even me, the author, writing about these women—I know that I ought to enter into their psyche and humanize them, give them agency, but it's genuinely quite difficult, because the reality of their circumstance is so dire. Several of their number have killed themselves. One is pregnant, she hopes that a baby will alleviate this circumstance somehow. Damien spends a lot of time on campaign—in summer, he will be gone, and perhaps he will be killed. That is what the women tell themselves.

What Damien doesn't understand is that in order to make this situation work, he has to make the experience of these women somewhat tolerable. Or he needs to constantly replenish their number through victories at war.

But if he made their situation tolerable, then at the very least he would have to account for their children, provide for them somehow. And he isn't really rich enough to do that.

One of these women, Alamanse, has learned Damien's ways, and she seems to participate most enthusiastically in what he wants. That's why he often sends her to the room of dignitaries. And from one of these dignitaries, who felt sorry for her, she has learned that Damien’s religion prohibits keeping someone of this same faith in captivity. She told the man that she would be happy to convert, and the man conferred with Damien, who laughed and said of course she would claim anything—a pagan could never truly understand the Lord's word.

Damien believed that God was happy with him. He believed this because his castle’s priest generally seemed happy with him, and said he was a savior of their faith, since he warred with the unbeliever.

But Alamanse had learned from some of the palace servants about the teachings of Damien’s deity, the “One God”. These servants claimed that there was a God who punished bad men and sent them to hell. That in the afterlife, men like Damien went to hell. On this, the palace servants were quite adamant. And people like Alamanse went to heaven, where they were rewarded.

Alamanse found this somewhat baffling. Her native belief system was just like the childhood belief system of the Paladin: you worshipped native spirits and asked them for concrete, earthly rewards—health, wealth, and strength. But this new belief system, with heaven and hell and punishment after death, was very exotic, very strange—Alamanse worried there was a language barrier, or something she didn't understand.

But the palace servant who'd been put in charge of the girls and their needs—this servant claimed no, she'd once seen a vision of hell. She'd seen it herself, had seen Damien's father, the old master, and he'd been burning there. And the servant's deceased mother and father were up in heaven, feasting and having a great time and sometimes spitting on Damien's father.

"You saw it?" Alamanse said.

"I saw it myself," said the servant, Therese. "Some people are given this vision of the afterlife, if they pray hard enough and are good."

So Alamanse started to pray. She started to learn. She questioned other people about this belief, and she learned, rather incredibly, that everyone in this castle believed that powerful people who were evil were punished after death. And good people, no matter their station, were rewarded. Many people in this castle believed it very fervently.

And Alamanse grew to believe it herself.

She did not know about the paladin.

And the Paladin didn’t really believe in this stuff about afterlives. He was the remnant of a quite different religious tradition that was much more vague about what happened after you died. In the Paladin's faith-tradition, there were lots of people who believed you transcended the earthy plane if you were pure enough, but the paladin didn't know about that stuff, and most of the people who did know that stuff were dead.

Ultimately the Paladin's faith-tradition wasn’t rich enough to support an apparatus of people who theorized about cosmology. The paladin survived because he wasn't a proselytizer of any sort. He didn't have any vision for how society should be organized differently. He was just an avatar for what was right. And most people understood that God, however they conceptualized him (or her) had chosen the paladin.

Damien remained in his rooms for a while. But, unbeknownst to him, his chief knight, Odric, had been talking to the other knights about killing him. They had all agreed that Damien needed to go. But the sticking point was the girls. What was to be done with them? The chief knight knew that ultimately, if they murdered Damien then...the girls would need to disappear. They would be inconvenient. One way or another, they would need to disappear.

Damien didn't have a wife. He had an heir, but the heir was weak—the King would probably intervene, reapportion the lands and responsibilities attached to this domain. And the girls were an inconvenience. They would have to disappear. But Odric was worried that if he made the girls disappear, then the Paladin would kill him. So he felt very stuck, very trapped by this circumstance.

But Odric was really over-thinking things. Because ultimately the girls did indeed disappear. During the confusion, they escaped.

You see, the palace servants did not hate these girls, they sympathized with them. This was a border region—territory was constantly changing hands. People who looked like these girls had lived here for years. These girls were racially distinct from the ruling class, but not from the ordinary people, not really. So the girls simply walked out, under the protection of the Paladin. They walked to the border with the Paladin, and he took them home.

It was never more complicated than that. They had a home, and he took them back to it. In their home, people spoke a different language, so the Paladin required the girls to interpret for him, but that was really the only barrier. And in this place too, ordinary people recognized the goodness in the Paladin—they had their own tales of people like him, who served justice—and they understood a holy mission.

As for Ser Andras, he remained behind under guard for a while. But when the girls were gone, the chief knight killed Damien and released Ser Andras, so he could tell everyone that Damien’s death had been well-merited.

When Ser Andras was free, he decided to make inquiries about the Paladin’s current whereabouts. The paladin was famous—a certain kind of person generally knew where he was. Ser Andras went down into the villages and looked for lintels with certain runes, and eventually people directed him to the Paladin.

When they rejoined each other, Ser Andras still wouldn't shut up about the hut they'd passed, where that man had clearly been mistreating his wife and kids.

"You saved these captive women, because they were being harmed by one of my kind, by a nobleman,” Ser Andras said. “But this other woman, this wife, because she was being harmed by your kind, by a villager, you did nothing."

"And do you think that you could solve this problem?" the Paladin said. "I act upon my beliefs—let me see you act upon yours."

So they went back to the village. And Ser Andras haunted that untidy hut. Everybody got so tired of Ser Andras asking, "Is there not something troubling about that household?"

The wife insisted nothing was wrong, but everyone in the village thought her husband was probably beating her too much. There was a certain amount that was okay, but this man was probably exceeding that amount.

And the village headman said: “Well, if we intervene, what will happen? This man, the husband, Hendrick, is a strong worker. His fields are productive. He has a good tenant-right, cash-rent, no customary duties, and the cash-rent is very low, hardly anything. If she wanted to leave, then she could. But she is from a village two days away. We don't know her parents, maybe they are dead, but in any case there is obviously something wrong with her home family, or she would go to them. So perhaps this is the best she can do. If he dies, then who inherits the lease? The lord will require some payment, some bribe, to transfer the lease, and whoever can pay the amount will get the land—His sons will lose everything.”

Other village elders reiterated these points: “Perhaps if she had friends in the village, she could appeal to them, but she keeps to herself….He is bad somehow, but there is nothing to be done. It is not a solvable problem.”

However Ser Andras was such a busybody about this, and they spent so many weeks on this—endless weeks while everybody had better things to do. And then during the nights, he would be so self-important, saying to the Paladin, "See, villages are not self-governing. They do not solve all their own problems."

The Paladin felt the problem was ultimately the lord. The wife was afraid of losing the lease. Afraid if they showed weakness, then the lord would take away their land. But the Paladin admitted that his position was weak. Something was wrong here. Something was rotten in this village. It was exactly the same situation as with Damien—yes, many people would be happy to come and take this man's farm, but those people would not want to care for his wife and children. So she had an incentive to keep quiet.

It was a problem. And perhaps now they had made it worse. The Paladin and Ser Andras had exacerbated this situation by giving it so much attention.

In this case, the Paladin worried that the man now had a reason to kill his wife. She'd brought trouble on him, so why not get rid of her. Then he could marry again—someone from some distant village would choose him, lured by his good lands.

"These people don't need a man with a sword," Ser Andras said. "They need a good lord, who can dispense justice, and who will make provision for the unfortunate."

Despite himself, the Paladin found this to be somewhat convincing. In some cases, situations that seemed complicated were actually simple. Like with Damien's women—he had known this was a solvable problem, even if Ser Andras hadn't. But the Paladin tended to gravitate towards those situations, and to avoid other situations which were also bad but which he didn't know how to solve.

And they still didn't know what this man was doing that was so terrible! They had no idea! Everyone thought he was just beating her, but maybe it was something worse. Maybe he was hurting the children. They did seem a little hungry, a little neglected. They had a haunted look.

It was a test. It was a trial.

And in this case, the real bravery belongs to the oldest boy, who had suffered for so long, keeping the secrets in this household. Amidst all this scrutiny, he finally went to the village headman, and he confessed what was done.

In many such cases, these boys are told to go home, or they are dismissed. The father comes and tells the village it's all a fabrication, and the village accepts the story. But in this case, because of Ser Andras and the Paladin, the whole village had already accepted that something was wrong in this household. Something needed to be done.

So the village came, and they took the children away. They were cared for by other men. And Hendrick was shunned. Nobody spoke to him or his wife.

After a few weeks, Hendrick disappeared. Nobody knew where he went, and nobody cared. The wife was judged complicit for her role in covering up this neglect. She went back to her home.

When the lord asked if anyone else would take the lease, the village insisted that it be given to this boy. Because he was a man. He had shown bravery, in protecting his family. And the lord knew this boy couldn't farm it on his own. He'd hoped to get a fat payment from somebody who wanted to buy the lease off him, but what could he do? There were no offers. So he let the lease be registered to this boy.

The village worked out a deal, where other men would farm the land for some years, on his behalf, and they would claim some reward. All of this was adjudicated by Ser Andras, who had no idea what was fair, and who found all this dickering to be quite fascinating.

But the Paladin had some understanding of the amounts that made sense, and that would make the men's time worth their while, so he acted on the boy's behalf and made sure his interest was represented well in the deal. Then because nobody could read or write, they did the usual thing in this village, and they all came together and repeated the terms a thousand times and everybody swore lots of oaths in front of their various saints, and then they slapped a young child, so he would hopefully remember this day forever.

And the Paladin and Ser Andras moved on.

Once the oversight was gone, this village could've screwed over the boy and taken his land from him, but they didn't, because this village was proud of this deal, and they were proud of how they'd acted in this situation. Many people talked about it, and it became part of the legend of Ser Andras and the Paladin—a legend that the village profited from.

In the end, Ser Andras gained the most from this episode. People said, Oh this man is different from other knights. He has true wisdom, and he dispenses true justice. Not like the rest of them, not like those noblemen.

P.S. This is the third Erdric story. He was introduced as young man in “The Good Guy Always Wins”, and his sidekick Ser Andras entered the picture in “The Tournament”.

I love how the Paladin and Ser Andras have complementary approaches to solving problems. Sometimes you do need to kill people with a sword, but also sometimes you need to stay focused and make a big stink and become very annoying to get things done! Ser Andras would do very well on a modern-day city council.

Nice, and these paladin stories just keep getting better