Back when short stories were popular, they were also bad...but in a good way.

Every year Penguin Random House publishes an anthology called The O. Henry Prize Winners. These books notionally contain the best short stories published in America in the preceding year.

There is no actual winner of the prize. All the stories are collective winners, and their award simply consists of publication in the anthology. I found it somewhat confusing. The prize also doesn't have a website. It's very unclear if anyone actually reads this anthology, but presumably many libraries buy it, because the O. Henry Prize has a long history—it was founded in 1919.

Most people who write short stories are aware of this prize. And they're aware that it was named after an extremely popular early 20th-century short story writer who wrote under the pseudonym "O. Henry". This writer, an ex-con named William Sydney Porter, was the most popular short story writer that has ever existed in America. For three years, he published a story every single week in the New York World's Sunday supplement. This supplement had a circulation of more than 500,000. Every single week it contained a story by O. Henry, for three years. He also published stories elsewhere, and many of his stories were syndicated widely.

The Sunday World wasn't the most popular periodical that existed at this time. There were several magazines that had higher circulations: Murnsey's and Lady's Home Companion may have had a higher circulation. But none of them published any writer with the frequency with which New York World published O. Henry.

During his heyday, which lasted from 1903 to his death in 1911, O. Henry got a lot of critical respect. He was known for writing plot-driven stories that often had surprise endings. Some critics did not like this, but many were enthused. He was called "The American Maupaussant".1 If you liked fiction in 1905, you had probably enjoyed at least a few O. Henry stories.

Almost immediately upon his death, O. Henry began to be derided as sentimental and kind of a lightweight, someone who relied upon cheap tricks for an effect.

I chased down a retrospective published about O. Henry in 1912, where this writer, Frederic Taber Cooper, tries to describe the O. Henry phenomenon. It's not a takedown, but it’s clear that even the year after his death, people are starting to agree that he was a minor writer, not particularly worthy of notice:

The meteor has blazed, and burst, and burned itself out ; and the interesting question not unnaturally arises, To what extent was O. Henry’s vogue justified? Is the popular verdict greatly in error? Does his fame of the passing hour rest upon a solid foundation?

The article is appreciative, but ultimately dismissive: O. Henry is destined to be forgotten.

Actually, O. Henry has had a long afterlife, because one of his stories, "The Gift of the Magi", is often taught in schools. I have no idea what they teach kids about this story, but most of us probably read it at some point early in middle school: it's about a couple who want to buy each other a Christmas present. The girl, Della, sells off her long, luxurious hair to buy a chain for her husband's antique pocket-watch. When she gives him the present, she learns that he's sold his watch to buy her some combs for her hair.

A lot of O. Henry stories are like this. "The Cop And The Anthem" is about a vagrant who's trying to get arrested so he'll have a warm place to spend winter. When his attempts fail—he can't even get arrested in this town!—he decides to turn over a new leaf and go find a job, only to get arrested for vagrancy.

In "Man About Town", the protagonist goes around trying to decipher this phrase. Who is a "man about town"? These seem to be people who aren't quite gentlemen, but aren't quite common, but who are these actual people? Can you point to one? At the end of the story he's hit by a car, and in the hospital he opens a newspaper story about the accident and sees himself described as "a man about town".

In many of the stories, the trick isn't nearly so easy to describe. In "The Duel", two friends debate whether the other person has sold out and become commonplace. We think we're on the side of one friend, who keeps saying, essentially, that this city destroys people:

“This town,” said he, “is a leech. It drains the blood of the country. Whoever comes to it accepts a challenge to a duel. Abandoning the figure of the leech, it is a juggernaut, a Moloch, a monster to which the innocence, the genius, and the beauty of the land must pay tribute..."

But then at the end, a girl sends this guy, the hater of New York, a telegram saying that if he leaves the city she will marry him, and…he doesn't do it. This is the ending to the story:

He kept the boy waiting ten minutes, and then wrote the reply: “Impossible to leave here at present.” Then he sat at the window again and let the city put its cup of mandragora to his lips again.

I would say most of his stories have more ambiguous endings like this. Endings that are harder to describe, but still feel somehow surprising, like a reversal of our expectations.

The Fall and Rise of a Minor Writer

At this point, you're probably thinking, "Why am I reading about O. Henry?"

The answer is that I've gotten very interested in the American short story, so I decided to read a volume by the foremost practitioner of the form—the man who is the namesake of one our oldest short-story awards.

O. Henry isn’t quite forgotten. In fact, I’d say his critical life-cycle is typical of many 19th and early-20th century writers. Basically, there was this wave of extremely judgmental critics—Dwight MacDonald is an example—in the 30s, 40s, and 50s who cleared a lot of writers out of the canon and dismissed them as being unworthy of critical attention: O. Henry even comes in for a mention in MacDonald’s influential essay on middlebrow culture, “Masscult and Midcult”.

Then in the 1980s and 1990s, people got bored of studying the big, canonical writers, so some academics went further afield and started to focus on popular writers. In O. Henry’s case, there was a volume published in 1993 that attempted to study his narrative techniques. This book led to a number of papers that attempted to analyze O. Henry’s appeal, and this steady increase in academic attention culminated in 2021 with the release of the Library of America volume, a selection of stories edited by Ben Yagoda. The release of this volume provided an occasion for mainstream reviewers to reevaluate O. Henry: the book was praised by Louis Menand in The New Yorker and Michael Dirda in The Washington Post, amongst others.

Thus, we stand squarely in the middle of a provisional O. Henry revival. At this moment, his reputation is higher than it’s been at any point since the 1930s. Whether his stock increases or not—well, it’s hard to say.

Okay, but should I read it?

I own the aforementioned Library of America volume, O. Henry: 101 Stories. More specifically, I read the forty stories in the section entitled "New York Stories", which contains stories from his New York period, when he got famous.

And I really enjoyed reading these stories. I liked them for the same reason the readers in 1905 enjoyed them: O. Henry writes about people from many walks of life. He writes about shopgirls, swells, criminals, immigrants, writers, actresses, and the moneyed elite. His characters speak in a variety of registers—it's hard to pin down any specific O. Henry 'type'. The dialogue is sometimes naturalistic, but equally often it's artificial and highly-elevated—in fact there's an O. Henry story where an editor criticizes a writer for always writing characters who speak in an elevated register during moments of tragedy.

The endings are fun! I like how they snap shut, bringing the story to a thunderous close, and they leave you thinking. In many cases, they leave you thinking, "Wait a second...is this actually a good ending?"

Because the O. Henry story is, in 2025, the definition of a bad story. The stories I've been describing are bad stories, by 2025 standards, because they rely for much of their effect on these surprise endings that, in many cases, don't flow organically from the plot. They feel contrived and artificial, like the authorial hand is at work.

But...that badness is also exactly why they're good. Because they're so different from any other story you're likely to read. I can read volumes upon volumes upon volumes of 'good' stories, and they'll all be good in the same way. They'll usually end on some carefully-chosen image, calibrated for the perfect level of ambiguity, that leaves a bell ringing in your head. What they're not going to do, is end with a joke, like "Man About Town" or with a contrivance that reveals the protagonist is a hypocrite, like "The Duel", or with a sentimental coincidence, like in "Gift of the Magi".

O. Henry arose from a very different fiction ecosystem

I was equally fascinated to learn about the magazine world that supported O. Henry. There are a number of journals from 1905 that have names we recognize: Harper's, The Atlantic, Scribner's. These journals published fiction, and most of the early 20th-century story writers whose names have endured—they were published by these journals. I am talking about Henry James, Edith Wharton, and Willa Cather. These journals had circulations in the 50-150k range.2

But then there were these other journals, like Munsey's, Lady's Home Companion, and the Sunday supplement of the New York World. And these journals published writers like O. Henry and Edna Ferber and Dorothy Canfield Fisher (two other writers I’ve been reading)—writers who are largely unknown today.

Later on, the dominant fiction magazines would be Lady's Home Companion and The Saturday Evening Post, which both had circulations in the range of two million, and out of the people who regularly published in these journals in the 1920s the only person whose reputation has endured is F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Of course people like Edith Wharton and Willa Cather did occasionally publish in these more-popular journals, but their reputations weren't associated with these journals in the way that O. Henry's was associated with the New York World, or Fisher's was associated with Lady's Home Companion, or F. Scott Fitzgerald was associated with the Saturday Evening Post.

People like Edith Wharton and Willa Cather generally derived their reputation from their publication in higher-brow journals, which were often far older, had long-established reputations, and catered to the pre-existing educated class.

These new journals, in contrast, catered to the new middle class. This is obvious when you look at them. Here, for instance, is a page from the a 1911 issue of the Sunday World:

There are articles here about taking a pleasure trip to Coney Island or about how you should walk around barefoot. It’s all about fun, cheap thrills. Stuff that felt very new and daring to the middle-class audience. The content is inviting and appealing—it speaks directly to the reader.

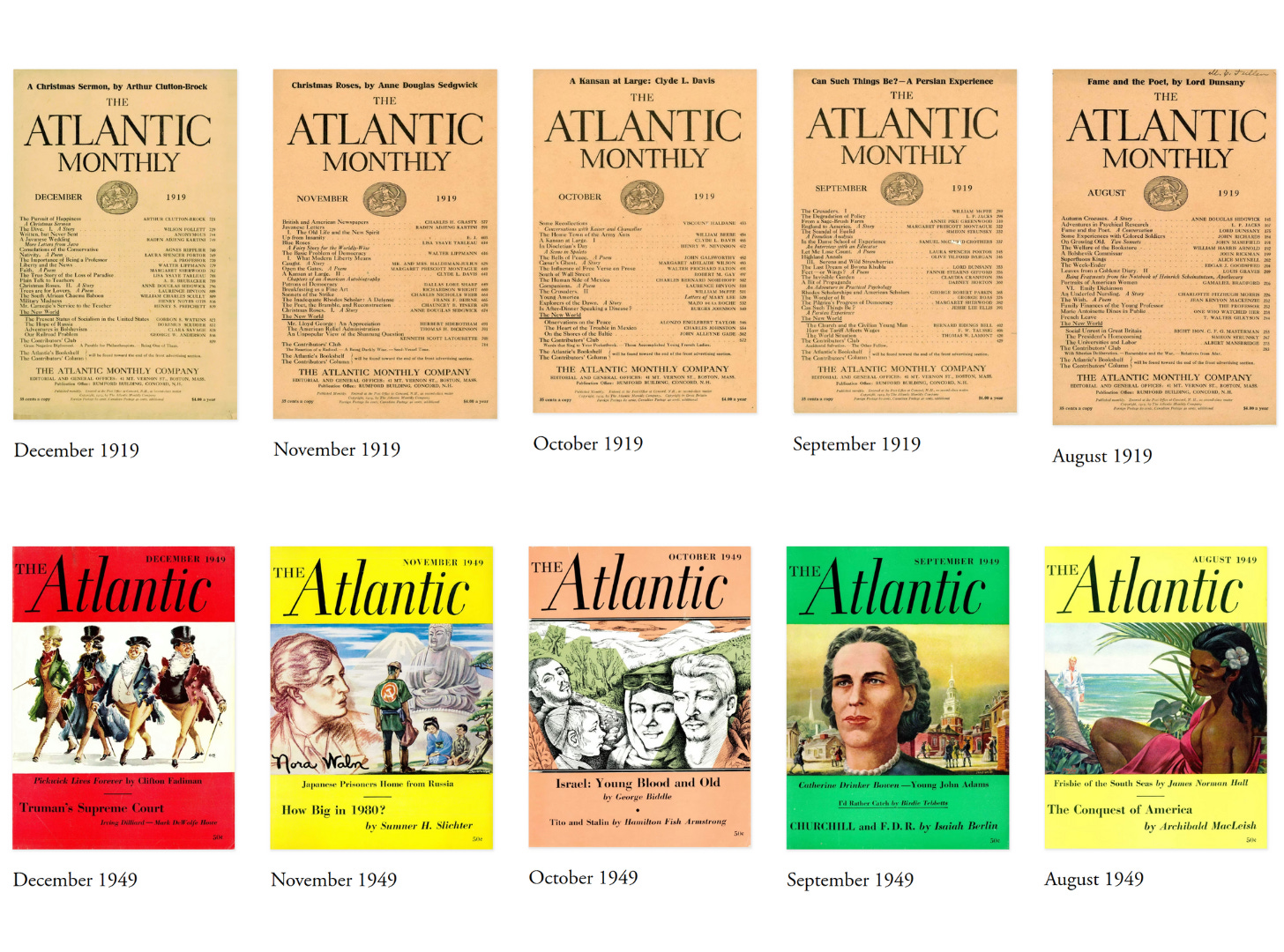

In contrast, look at a 1911 issue of The Atlantic.

As far as I can tell, this is what the Atlantic really looked like. It was all text. There were no images anywhere in the magazine, aside from a few pages in the back for advertisements. The articles are extremely serious: there’s a short story that ends “Andoni never saw her again” and some article about Robert E. Lee and his army.

Even the cover wasn’t an image! The cover looked like this! It wasn’t until 1947 that they finally started putting full-size color images on the cover.

Imagine you’re a housewife in 1910 who’s graduated from secondary school but never gone to college. Your husband owns a store. You want to know more about the world. Now think about what journal you’re going to subscribe to. Are you really going to subscribe to The Atlantic? Of course not—the journal is so forbidding! It’s basically got a Keep Out, Pleb sign on the cover. In contrast, The Sunday World is extremely inviting—it’s a journal written with you in mind.

Which is to say, magazines then were just like magazines today. Each magazine had their own brand. Their own type of content. Today, if you're a centrist who loves being upset about stuff, you read The Atlantic. If you want salacious gossip about how New Yorkers live, you read New York. If you want to feel mildly-educated about a large number of topics, you read The New Yorker. If you want to read summaries of various recently-published nonfiction books, you read The New York Review of Books. If you want takedowns of hot literary novels, you read The London Review of Books.

What differentiates the modern world from the world of 1905 isn't that there are different magazines that offer different products, it's that in 1905, these journals (Munsey's, Lady's Home Companion, The Atlantic, Harper's, etc) all published fiction. Even the newspaper published fiction! O. Henry was basically published by the newspaper!

But today, almost none of the journals I've named, aside from The New Yorker and Harper's, regularly publish fiction on their print edition (The Atlantic publishes stories in its online edition). There are a number of high-circulation journals that used to publish fiction until quite late in the 20th century, but which no longer do: journals like Cosmopolitan or Good Housekeeping or Reader's Digest or Esquire. Other large circulation general-interest journals that used to publish fiction—Playboy and Redbook and Lady's Home Companion and McCall's—have gone out of business entirely.

Generally speaking, with the exception of The New Yorker and Harper's and the online fiction section of The Atlantic, the only journals that publish fiction today are literary journals—they are journals whose explicit purpose is, at least in part, to share short stories. The most popular of these journals (Paris Review and Granta) seem to have a circulation in the 20k range. And that is the sum total of the audience for short stories. Large-circulation magazines don't publish short stories because their perception is that there isn't a particularly large subset of their audience that wants to read them. Even The New Yorker, the largest-circulation magazine that publishes fiction, has steadily reduced the number of short stories it publishes per year, and many weeks the story it publishes is really a novel excerpt.

The rise of the short story

In learning about O. Henry, my main question was, "Wait a second, why were there short stories in the 1905 equivalent of New York Times Magazine?"

Well, the short answer is that people wanted to read them. O. Henry usually got paid between $250 and $500 per story. That was a lot of money: somewhere between $10,000 and $20,000 in modern terms. If they could've paid him less, they would've. They paid him this money because their perception was that an O. Henry story could drive circulation numbers and sell some copies of their magazine.

But why did people have this taste for short stories? Why was this something people wanted to read at all?

Well, to learn the answer to that, we have to go back to a hundred years before O. Henry, to the early 1800's, when the print periodical first arose in America.

My understanding is that in a lot of early journals and newspapers, fiction and nonfiction weren't that clearly delineated. You were reading a journal. It contained various pieces, about various sorts of phenomena in the world. Some of these pieces were basically fictional: they might be told in the first-person, but they were about things that hadn't happened.

Sometimes this was clear, and sometimes it wasn't. Out of the writers we still read, Edgar Allan Poe, is our best glimpse into this early magazine ecosystem. Poe sometimes published stories that his editors, at least, claimed to actually think were true (“The Balloon Hoax” is an example). Other authors and other journals did the same thing. Although he wrote sensation tales himself, Edgar Allan Poe also satirized these kinds of stories in a piece entitled: “How To Write A Blackwood Article”.3

Many times a story would be related as an anecdote or discovery, or as a local legend or folk tale. You knew the tale was fictional, but you were told that it was a real fiction that already existed in the world (i.e. it hadn’t been invented by the author)—Washington Irving’s most famous fictions, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, were supposedly stories he’d overhead in upstate New York.4

And even many things published in the 19th-century as truth were fictionalized or embellished or even fabricated in various ways. Over time, people became sophisticated. They started to understand which types of pieces were likely fictional. And stories started to develop various traditions and conventions.

And then, in America in particular, there were a bunch of literary critics throughout the 19th-century who argued that the short story was a literary form that was deserving of more attention. In the late 19th-century, William Dean Howells argued that the Americans had perfected the short story:

I am not sure that the Americans have not brought the short story nearer perfection in the all-round sense that almost any other people, and for reasons very simple and near at hand…The success of American magazines, which is nothing less than prodigious, is only commensurate with their excellence.

A number of guides appeared in the late 19th-century that were about how to write a good story. As The Cambridge Companion to the American Short Story relates:

In what could be considered the birth of creative writing, the first guidebook was published by Sherwin Cody in 1894, How to Write Fiction, Especially the Art of Short Story Writing; within two decades, nearly all of the educational publishing houses in the country were issuing them for aspiring authors. An important early bibliography lists fifty-nine works devoted to the genre published between 1898 and 1923.

Subsequently, in the early 20th-century, there was a major push to build institutions to recognize the short story. That's when The Best American Stories and The O. Henry Prize were both founded.

Basically, the short story was something that arose from the pages of magazines and journals. It was something people read to be informed and entertained. After short stories had been around for a few decades, people started to consider the idea that maybe these things had some literary merit. Then, after a century, the idea that stories had literary merit got formalized.

The short story wasn’t killed by TV

Now...why did the short story disappear from the pages of these journals? Well, that is a question without an answer. It can't be attributed to the rise of radio and print and movies, because if that was the case, the journal itself would've disappeared, and, as we know, there are still plenty of high-circulation magazines around.

Moreover, I will note that many of these journals still publish first-person pieces that very much resemble stories (the New York Times's Modern Love is entirely composed of such pieces). These stories are purportedly true, but they contain dialogue and images that the reader knows, on some level, are fabricated, because we know that human memory is quite fallible and unreliable and it’s impossible to accurately remember the past in such detail.

However, a convention has arisen around these pieces where so long as nothing in them can be explicitly contradicted by documentary evidence, we are allowed to keep believing they are true. Basically, you can lie, but you have to do it believably.

And people are often very interested in these pieces, these personal essays. They quite frequently go viral online and are shared widely. They are a major driver of subscriptions and revenue for many journals. The best writers of these pieces often get book deals and achieve lasting literary success, in various forms.

My point of view is that the Modern Love story is the closest analogue in modern times to O. Henry's tales. It is a simple form, that offers easy, reliable pleasures. It depicts a broad swathe of humanity, but people are portrayed in universal terms that show we are all ultimately the same. And each column usually has some trick or innovation that makes it slightly different from the others. Yes it's different, because these stories are purportedly true, but we also know that this difference, between truth and fiction, didn't necessarily matter to earlier generations in the same way it matters today.

Now as for the broader question: should you read O. Henry’s stories yourself? Well...it's not a bad way to spend an evening. They're easy to read and quite entertaining.

But as I was reading, I had a devilish idea: These stories are in the public domain. I bet I could steal O. Henry's tricks for my own tales and nobody would see them coming. So I wrote down a list of about forty different tricks he used, and I hope to deploy them over the next year or so (with proper credit given, of course.) I am pretty sure these tricks will work just as well in 2025 as they did in 1905, but either way I'm very interested to make an experiment of it.

Elsewhere on the internet

During my hiatus, Woman of Letters got mentioned twice in mainstream publications.

In Vulture, Emma Alpern listed my newsletter in the article: “Substack Is Where Writers Go To Be Weird”. Was nice to see The Republic of Letters and Marlowe Granados mentioned as well. They have good newsletters, but more importantly they both seem to be having a lot of fun, if you don’t subscribe, you really should.

In The New Statesman, Henry Oliver mentioned my newsletter as a reason why we shouldn’t feel depressed about the state of literature.

Also, I sent out one of my paid posts last week. It’s all about the process of putting together my latest book: What’s So Great About The Great Books?

P.S. I think I’m back from my hiatus, but I am also making a final push this week to turn in the aforementioned book, so I reserve the right to take off next week if I need to.

Mary Moss, writing a review of one of his collections for The Atlantic in 1905, said the comparisons were well-merited: “Even a book notice which claims for O. Henry the best qualities of Dickens and Maupassant (one wonders what Dickens would say to that yokefellow) is not enough to overweight The Four Million.”

I got these figures from a book entitled: The Magazine Century.

Longtime readers will know I’m not the biggest Poe fan. I wrote more about him here.

This is kind of an amusing post for me to read, because when I was in HS almost all my friends read O. Henry! I don't think this was typical for high schoolers in the 2010s, but the reason for this is that they all played quizbowl, an academic trivia competition that happened to have a lot of O. Henry questions. O. Henry got asked about a lot because he was in a perfect sweet spot: he was "accessible"—that is, even a middle schooler could get something out of reading his stories, but he also wasn't one of those authors like Edgar Allan Poe where ~everyone~ had read his greatest hits. And his stories were also quite easy to write about in a clear way, so writers didn't have to spend as much effort on such questions. The end result is that O. Henry was one of the top 25 most common authors to appear as an answer in competition, and maybe even top 5 at lower levels.

People who got deeper into quizbowl didn't consider O. Henry to be "high literature", but he was one of those authors that you could always casually reference since just about everyone had encountered his stories in one way or another.

Here's an example of someone dropping an O. Henry reference in a competition question in an almost meme-like way:

> A musical artist who gained fame under a stage moniker named after these objects claimed in one song that he, “had a sit down with Farrakhan” and “Turned the White House to the Terror Dome.” Della sells her hair to buy Jim one of these objects for his watch in "The Gift of the Magi", and in calculus, a rule named after these objects states that the derivative of (*) f of g of x is f prime of g of x times g prime of x. The Communist Manifesto claims that the Proletarians have nothing to lose but these objects, and The Social Contract begins, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in” these objects. Fenrir was bound in, for ten points, what metal objects composed of several connected links.

ANSWER: chains

(source: 2017 Ladue Invitational Spring Tournament https://quizbowlpackets.com/1978/)

(I'm planning to write a post about quizbowl at some point. Even though I would expect most Gen Zers on Substack to have at least heard of quizbowl, I don't get the sense that older readers really know much about what was going on inside this somewhat unusual subculture.)

Short stories are always popular because they give a reader the essence of life in the short form, and if you love a story, you could read it endlessly, as I do with Chekov's "Boring Life." I remember O. Henry's "The Gift of Magi" for over 60 years; this story was so romantic and dear to our Soviet children. To read such a light opinion of yours now, "I have no idea that they teach kids about this story," is very strange. And we still reread Edgar Allan Poe, in English, now.