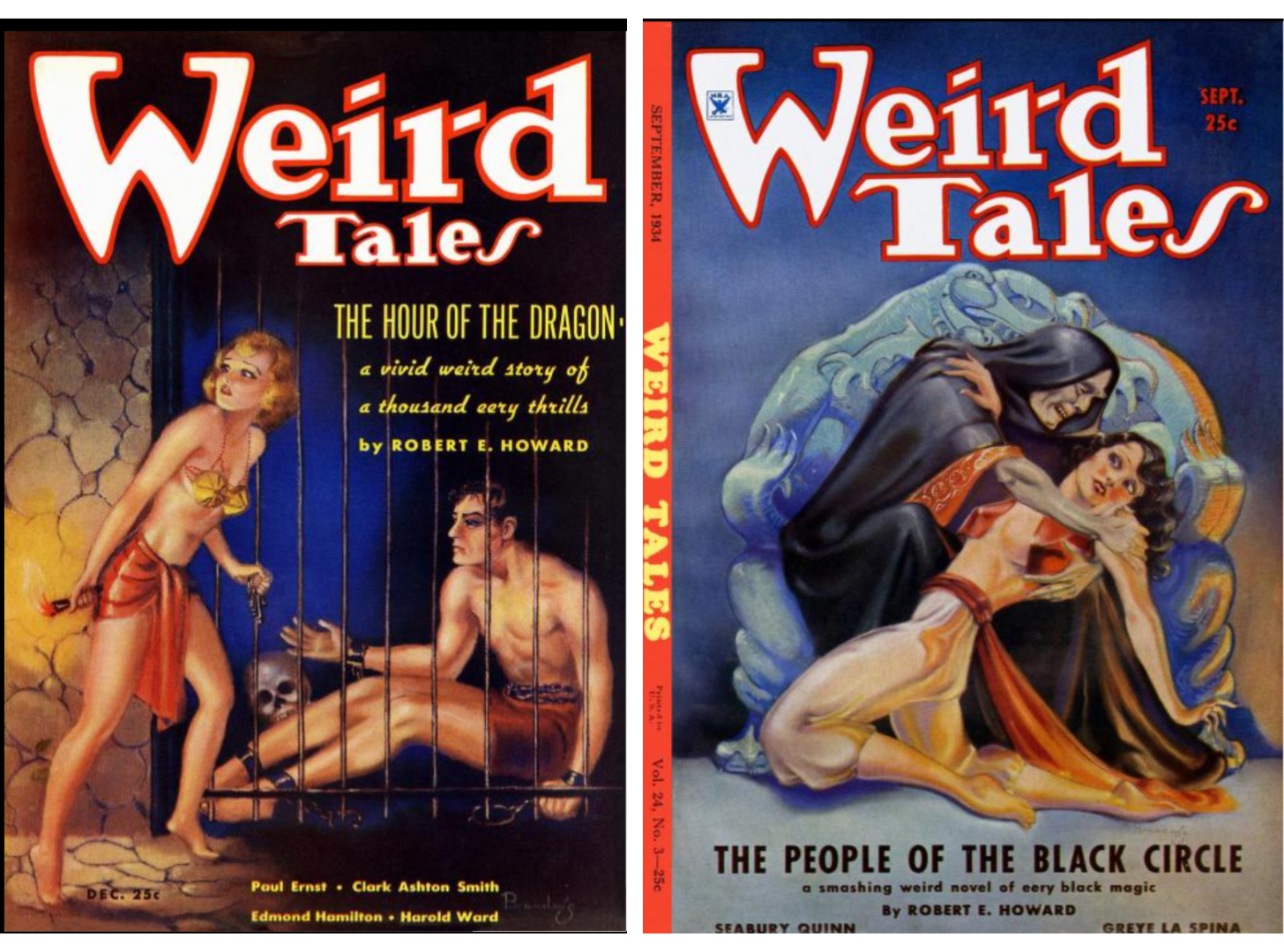

This pulp fiction journal had sleazy covers and a low circulation. But it still produced an iconic character.

For the past week, I’ve been reading a set of stories, written by Robert E. Howard in the early 1930s, about a tall, brawny, sword-wielding adventurer named Conan.

These stories take place in a fantasy world that resembles the early Iron Age, and in these tales, Conan is sometimes a thief, sometimes a war-leader, sometimes a King, sometimes a pirate, but he is always a simple guy who doesn’t care for civilized ways, and who tends to get into a lot of conflict with the assorted nobles, wizards, merchants, and other rich, settled people amongst whom he finds himself.

These Conan stories were originally published in a pulp fiction journal called Weird Tales that specialized in fantasy, science fiction, and horror stories. And the most interesting thing about Weird Tales, and about pulp fiction in general, was that it was a niche product.

In the larger fiction journals, like The Saturday Evening Post, there were stories for men, women, boys, girls—the whole family. That wasn’t true with Weird Tales. It was a journal targeted to young men and boys. And it was a journal with a relatively small circulation, by 1930s standards, which struggled financially and often had difficulty paying its writers.

Nonetheless, we still read Conan today because he resonated very strongly with this niche of readers. These readers, some of them, built a part of their identity around liking these stories, and they fought for decades to republish these stories and to give them some broader critical attention.

I have to say, having now read a number of Conan stories, I also feel a desire to explain how and why they’re good. Because on the surface, these stories are not good. That’s because the writing is quite overwrought and full of cliches. For instance, here’s a description of Belit, the Pirate Queen:

She was slender, yet formed like a goddess: at once lithe and voluptuous. Her only garment was a broad silken girdle. Her white ivory limbs and the ivory globes of her breasts drove a beat of fierce passion through the Cimmerian’s pulse, even in the panting fury of battle. Her rich black hair, black as a Stygian night, fell in rippling burnished clusters down her supple back. Her dark eyes burned on the Cimmerian.

This passage is a typical example of how these stories write about women. Usually at the first introduction of a woman, there’s a long passage where the narrator tries to convey that she is extremely hot.

The narration generally takes this world, and this life, extremely seriously, and will often break out into a long description of how awesome and cool Conan is.

War was his trade. Life was a continual battle, or series of battles; since his birth Death had been a constant companion. It stalked horrifically at his side; stood at his shoulder beside the gaming-tables; its bony fingers rattled the wine-cups. It loomed above him, a hooded and monstrous shadow, when he lay down to sleep. He minded its presence no more than a king minds the presence of his cup-bearer. Some day its bony grasp would close; that was all. It was enough that he lived through the present.

If you were submitting stories to a science-fiction or fantasy journal today, in 2025, and you turned in a story written this way, it would get rejected, because amongst fans of contemporary sci-fi short stories, this sort of writing is a source of derision.

Nonetheless, I have to say…I enjoyed reading Conan. I even enjoyed reading these passages. The very passages you’ve just read—they are the passages I clipped out as being unusually good! Because these are the most Conan-like passages I came across, and the whole reason to read Conan is for passages like these.

Nor am I alone in enjoying Conan. He is beloved by a surprisingly large number of people! When I wrote about him on Substack Notes, I got tons of people saying they love Conan too. And all of us have this same confusing desire to try and explain how it is possible for him to be good.

The world that created Conan

As I mentioned earlier, Weird Tales was one of the first magazines to specialize in stories of fantasy and horror and science fiction. These kinds of stories had existed for a long time, since Edgar Allan Poe, and they were a mainstay of several other adventure-story magazines like All-Story. But Weird Tales was founded in 1922 as a journal that would exclusively publish these kinds of fantastic, horrifying stories.

During the 1920s and 1930s, there were three types of fiction magazines:1

The slicks published on slick, glossy paper. Examples are The Saturday Evening Post, Redbook, Collier’s, McCall’s.

The highbrow journals used to publish on book paper, a high-quality matte paper like what you’d find in books. Examples are Scribner’s, Harper’s, The Atlantic.

And the pulps published on cheaper pulp paper. Examples are Weird Tales, Adventure, Black Mask.

It is not a simple matter to distinguish these journals. For one thing, there were a number of writers, like Tennessee Williams and William Faulkner, who wrote for all three of these categories. For another, at least one of these categories—the slicks—was extremely heterogenous in terms of what it published: the slicks published adventure stories, and they published highbrow authors, and they also published their own category of middle-brow short story (which I’ll describe in another post) that was unique to these journals.

Generally speaking, the slicks had higher circulations, in the one to two million range. They also had more colorful covers, more complex layouts. The highbrow journals had often had simpler covers, fewer advertisements, simpler layouts, and circulations under 150k.2

The pulps were the most marginal of these categories

Pulp journals were cheaper to produce—they were printed on cheaper paper and paid their contributors less—which is probably what enabled publishers to put out niche, special-interest journals like Weird Tales. It was rare for a pulp journal to have a circulation above 200k, and many of them (including some of the most iconic) had circulations that were far less.

When it came to the pulps, the tendency was towards an increasing variety and proliferation of titles. At the beginning of the century, you had high-circulation adventure journals like Argosy, which had 500,000 readers, but as time passed, more and more pulps were created, and they often had very specific niches. For instance, there was a whole category of sports pulps, which only had sports stories. And even within that category, there would be pulps that were solely about a single sport: Fight Stories only had boxing stories, for instance. In the 1930s, there were around two hundred pulp fiction journals, most of them publishing monthly (though weekly pulps also existed).

The pulps are in some ways the most difficult of these categories to understand, because there were so many, and there was no journal that dominated the rest, the way The Saturday Evening Post came to dominate the slicks, or The New Yorker came to dominate the highbrow journals. Although combined sales of the pulp fiction journals probably equaled those of the slicks, the sheer number of titles meant that any given pulp usually had a relatively small readership. From 1922 until it ceased publication in 1954, Weird Tales rarely exceeded a circulation of 50k (whereas in 1930 the The Atlantic had 150k in circulation and or The Saturday Evening Post reached two million). Weird Tales tended to pay Howard somewhere between $70 and $130 per story—only a fraction of the $300 to $500 that The New Yorker paid, to say nothing of the $3000 to $5000 an author could get from The Saturday Evening Post.

Writing for the slicks and highbrow journals not only paid more, it also offered a longer-lasting career. The highest-regarded writers for the slicks and highbrow journals often won awards, were reprinted in Best American Short Stories, were reviewed in major periodicals, and saw their works collected into books that sometimes became bestsellers in their own right. In contrast, this treatment was rarer for pulp writers—its not that pulp fiction authors didn't come out with books, they definitely did, but they generally had a harder time getting publishers interested, especially if they were writing science fiction or fantasy. With Conan, the stories never appeared in book form until the 1950s, long after the author’s death.

Physically speaking, the slicks and highbrow journals were designed to last—it was not uncommon for families to bind these journals into yearly-volumes and keep them in numbered sets in a bookshelf—while the pulp journals were inherently disposable. They were like newspapers. You read them, you got rid of them. So not only could you only read the Conan journal in the original publication, but even that original publication was inherently disposable and not designed to last.

This general disposability meant that writers like Robert E. Howard were simply never mentioned in mainstream literary periodicals, not even sneeringly, and had essentially no literary footprint. If you were reading the archives of the major literary periodicals of the day, you might not even know such a thing as Weird Tales existed, much less run across the name Robert E. Howard.

As a cultural phenomenon, the pulps also had the shortest run. By the 1950s, the pulp era was largely over, replaced by comic books. It took until the late 1990s for the slicks to lose their cultural relevance, and the highbrow journals continue publication to this day.

The pulps gave rise to fan culture

However, the pulps have one advantage over these other categories, especially over the slicks, in that they gave rise to an intense fan culture. This means that pulp authors, pulp themes, pulp stories, have continually been reinjected into our culture because of these fans. Fans of pulp fiction created various communities dedicated to perpetuating the art found within this stories. The community where I began as a writer, the science fiction world, had its beginning in these pulp journals. Because of the patronage of this community there is one science fiction journal whose publication has continued uninterrupted from the early pulp era (Analog) and there are two other journals that have been published continuously since the late pulp era: Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. There are also a number of other journals publishing today that trace some spiritual lineage to the pulp era.

In the 1930s, these fans started to have conventions. They created fanzines: amateur publications that they mailed to each other, where they would discuss topics related to pulp stories. At the World Science Fiction Convention, they began to give out awards for the best story published in the previous year.

In the 1948, two science fiction fans started Gnome Press, with the aim of republishing some of these classic pulp stories. They published the first collections, for instance, of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation stories. They were also the first to reprint the Conan stories in book form. The press was troubled by financial difficulties, had issues with distributing books and paying its authors, but it proved there was a market for these books, and shortly thereafter some better-capitalized publishers started sci-fi/fantasy lines. The Conan stories were subsequently republished by Ace in the 1960s, by Berkley in the 1970s, by Tor in the 1990s.

What’s interesting about Conan is that fans have kept him alive for a hundred years, and there’ve even been critical volumes (created by amateur literary critics) devoted to discussing his style, themes, literary genealogy, and impact, but…he has never quite crossed over and become canonized.

Other pulp fiction writers—Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith (the latter two published primarily in Weird Tales)—made the jump. They got reissued by Penguin Classics. They got Library of America volumes. They got some kind of professionalized literary attention. Robert E. Howard never did.

Howard is part of what I like to call “the shadow canon”—writers that are really old, continuously in print, highly-beloved, but which are generally not taught in universities or discussed by academics. The shadow canon is smaller than the regular canon, but it includes Asimov, Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, Dale Carnegie, Roots, and I’m sure many other books that are slipping my mind. The shadow canon exists because intergenerational word-of-mouth exists—universities and book reviews and reading lists are not the only place people find out about books. I started reading The Foundation because my mom read it as a girl in India—now the TV show is surely introducing the novel to a new generation of readers.

Conan was serious business

I think what struck me most about Conan was this: I used to read submissions for a sci-fi/fantasy journal, Strange Horizons—over one year I read about 900 stories—and many of these stories used themes, settings, characters that were somehow inspired by Conan; however, in an almost all cases, the stories put some spin on it—they attempted to deconstruct or subvert this hero. They either played him for laughs, or they gave him some kind of angst. They never played it straight. It’s kind of like princess tales. You never see a princess anymore where she just sits around and gets rescued by a man. She’s always taking matters into her own hands—she’s always tough and independent.

Similarly, with fantasy stories today, you never see a story that just wholeheartedly believes in its strong, hunky barbarian protagonist. They almost always put a spin on him.

Whereas these Conan stories are so serious! The author, Robert E. Howard, was quite young when he wrote these stories: he died by suicide at age 30, so he was in his mid-twenties when he wrote most of the Conan tales. And they seem like a very naked fantasy of unlimited power, strength, sex appeal. They go down directly into the id.

There is no super-ego here: there is no doubt, no self-censorship—a fact one of the stories remarks upon. At some point Conan is fighting a beast, and the narration says:

The monster below them, to Conan, was merely a form of life differing from himself mainly in physical shape. He attributed to it characteristics similar to his own, and saw in its wrath a counterpart of his rages, in its roars and bellowings merely reptilian equivalents to the curses he had bestowed upon it.

Conan is a beast himself, and as such he's always dead certain of his course of action. Moreover, he is a beast who always wins, always gets the girl. It’s really very stimulating.

And for this kind of tale, the writing also needs to have zero doubt. This writing is filled with a fanatical sense of conviction. Every line screams out that this story is deadly important and needs to be taken seriously—there is no subversion, no winking to the camera. It is a really impressive performance.

And…that’s why Conan is good.

It’s no surprise that academia hasn’t taken him up, because what is there to say? Conan is awesome. It’s all written right on the surface.

I will say, I read one critical volume about Conan, The Dark Barbarian, that was edited by a fan, Don Herron, and this volume had an essay that tied Conan to the hard-boiled tradition. That Conan is basically a hard-boiled detective hero (a la Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op) transferred to a fantasy world. There was another nice essay about the existentialist philoosophy that seems espoused by Conan. There’s plenty of smart things to say! In fact, I am sure a better critic than me could say something very interesting, about the way this writing, on the level of the line, is perfectly calibrated to the needs of the story.

But when it comes to preserving and enjoying these stories, all this apparatus is unnecessary. The simplest explanation for his appeal is the truest one: he is a naked power fantasy, and…these kinds of fantasies are very fun.

The types of Conan stories

There are three major Conans. There’s Conan the thief, Conan the adventurer, and Conan the King. In some stories he is young: he’s a hired-hand, scrabbling for adventurer in the interstices of the settled world—in these stories he’s often plotting to steal something, or he’s on the run from someone. In other stories, he’s more established: he’s the Captain of the Guard or the leader of a war-band. And then at some point in his timeline, he is serving as a mercenary captain in the army of the King of Aquilonia, and he kills the King, overthrowing him, and usurping his throne, and there’s a set of stories where King Conan fights to keep this throne.

The three Conans seem quite different. In the King Conan stories, he is distinctly middle-aged, more cautious—he’s weary of war and conquest, anxious to make sure his citizenry is happy under his rule. His portrayal is clearly very influenced by King Theodoric, the Ostrogothic King who usurped the Western Roman Empire, and who (at least reputedly) went to some lengths to integrate his people with the existing Roman elite. The best of the King Conan stories is “The Phoenix on the Sword”, where Conan struggles haplessly against the rebellious undercurrent in his subjects.

When I overthrew Numedides, then I was the Liberator – now they spit at my shadow. They have put a statue of that swine in the temple of Mitra, and people go and wail before it, hailing it as the holy effigy of a saintly monarch who was done to death by a red-handed barbarian. When I led her armies to victory as a mercenary, Aquilonia overlooked the fact that I was a foreigner, but now she can not forgive me.

In the war-leader stories, you have the most classic Conan—strong and confident, somewhat brash, anxious for war and conquest. He’s always defeating other chieftain and captains and pirate kings and usurping their bands, or carrying off women and doing classic barbarian stuff. The best of these is “A Witch Shall Be Born”, where Conan literally gets crucified by a usurping witch-queen, then comes down off the cross and takes the city by storm.

Then in the Conan the thief stories, he usually seems a bit more hapless, more confused. The best of these is “The God in the Bowl”, where Conan gets caught robbing a temple and gets involved in a murder-mystery.

Some Conan stories also have a cosmic-horror element, where the hero encounters some eldritch foe from another time and place. The best of these tales was “The Slithering Shadow”, where Conan stumbles on a city full of hapless dreamers, who are being stalked by a terrible demon. As one of the women in the city explains:

For untold generations Thog has preyed on them. He has been one of the factors which have reduced their numbers from thousands to hundreds. A few more generations and they will be extinct, and Thog must either fare forth into the world for new prey, or retire to the underworld whence he came so long ago….They realize their ultimate doom, but they are fatalists, incapable of resistance or escape.

That was a particularly good story, which I highly recommend.

Some of the stories are better than others. There are a few Conan stories where the pacing feels a bit slow, and the adventures seem somewhat rote. This is particularly true of the two longest Conan stories: “The People of the Black Circle” and “The Hour of the Dragon”.

If you’re looking into reading Conan, all the original stories (i.e. those completed by Robert E. Howard during his life) are reprinted in these three volumes: of these, I recommend the first (The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian) and the third (The Conquering Sword of Conan)—the middle volume (The Bloody Crown of Conan) is primarily comprised of the two long tales that I don’t recommend.

At his worst, Conan can be pretty tedious—just a lot of running around, meeting and killing various interchangeable enemies. But at his best, Conan is like James Bond, and he is good for precisely the same reason: the continuous juxtaposition of sex, danger, and decadence. In Conan, you have these fantastically old cities and temples, that reek of immense age, which are often haunted by gods and demons and wizards, and then you have this simple guy who cuts through all these complexity with the force of his blade, and who gets the girl while he does it.

Is Conan literature?

You know…the term ‘literature’ is useful for getting people to read stuff that they wouldn’t otherwise read. People wouldn’t read Proust if they didn’t think it was literature, and they should read Proust, so it’s good to have that term. But with Conan, the term seems so unnecessary. There is still a lot of life left in Conan. He still acts on the modern nervous system exactly the way he acted on the nervous system of young men in the 1930s. There’s no need to mess around here, try to rehabilitate or revive him. He is strong, and he is healthy. There is a good chance he will outlast us all.

The racial politics of Conan are not good

Conan’s treatment of race is difficult to ignore. There are many, many Conan stories that feature hordes of nameless Black people. And in at least three stories (“Hour of the Dragon”, “Queen of the Black Cost”, and “Jewels of Gwahlur”) you have the same thing, where you’ve got these nameless black people that are ruled over by a white person. There’s also repeated mentions of Conan’s whiteness, in a way that makes the subtext very clear: he is a white-skinned barbarian hero who runs around physically dominating savage Black people and decadent brown people.

I will say, there is another famous writer whose work appeared primarily in Weird Tales: H.P. Lovecraft. And Lovecraft’s work seems much more racist than Howard’s. Lovecraft has several stories that are very explicitly about non-white people being terrible and evil—I’m thinking particularly of “The Horror at Red Hook”, which is about some non-white people in Brooklyn who are demon worshippers and are kidnapping women for their cannibalistic rituals.

In contrast, it's true that the Conan stories partake of some kind of racial paranoia or power fantasy, but it doesn’t feel quite as bad—the effect is similar to watching the Rocky movies, where you’ve got poor, downtrodden Rocky Balboa, and he’s always beating up these rich, powerful Black guys, and you’re like…what are these movies trying to say? Well…it’s obvious, but it feels good-natured enough that it’s still possible for non-white people to enjoy it.3

The death of the short story

Lovecraft is the other iconic writer produced by Weird Tales. I hope to read his stories at some point and write about him as well.

There’s also, rather incredibly, another small pulp journal that also produced two literary stars: Black Mask published all of Dashiell Hammett’s novels and many of Raymond Chandler’s stories. However for these writers I don’t know if their short fiction really constitutes their best output, and I don’t have a strong desire to reread their novels—I read them all ten years ago when I went through a detective fiction phase.

My intention after I wrote about Raymond Carver was to write about some other 20th-century masters of the short story—Hemingway was going to be next—but as you can see I’ve gotten hopelessly sidetracked.

My problem is simple. There is this type of fiction we all know about—the highbrow story, the New Yorker story, the type of story you learn to write in MFA courses—and for the last thirty years, everyone in the literary world has been wondering what happened to this story. Why does there seem to be so much less interest in this type of fiction? And they look back at the 20th century, when Old Man and the Sea was reprinted by Life, and they think…what changed?

Well, to me, the answer is that Hemingway existed in a world that contained pulp short fiction and middlebrow short fiction. And that these two types of fiction were, in some mystical way, responsible for the vitality of the short story. The literary short story defined itself by not being this other kind of story. And then this other kind of story disappeared, but the literary story hung on, decade after decade, as a sort of remnant, but without the other forms to war against, the highbrow short story lost its sense of purpose.

That’s my theory, and perhaps in some later post I will develop it in more detail.

What I do, in my own short fiction, is clearly not a highbrow New Yorker type story. It’s something different—a form whose pleasures are much more immediate and much more accessible. As such, I personally have a lot more to learn from writers like Robert E. Howard and O. Henry than I do from Raymond Carver and Ernest Hemingway—I respect the latters’ work immensely, but I did an entire graduate degree (an MFA) where I assimilated their influence, and now it feels right to go looking further afield for other influences.

Which is a long way of saying that I’ve written a ridiculously-earnest Conan-type story of my own that you’ll hopefully be reading this Thursday: it’s about a virile, rugged twenty-year-old Paladin who’ll lose his powers if he has sex.

If you want to know more about this taxonomy, I recommend this extremely helpful journal article I found on the subject.

I will note that the story is complicated. During this period, many journals altered their size, paper quality, and format—so journals often seemed more pulp-like or slick-like or highbrow during various points in their history. What I am identifying are general tendencies, not hard and fast rules

I was talking to BDM about Conan, and she clued me in to Charles R. Saunders, a Conan fan who went on to write, Imaro, a distinctively African take on the barbarian trope. From his NYT obituary:

As a child he had been enthralled by the fantasies spun by white writers like Robert E. Howard, who created Conan the Barbarian, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, who created Tarzan, the white African figure embodied most famously on the screen by Johnny Weissmuller. But he came to recognize the racism inherent in such works. Imaro was the result.

Good post. The one thing missing is crediting Howard with the invention of something so compelling, out of his own youthful fervor and earnestness, that he created an entire genre which has lived on and ramified into countless stories over nearly a century. Howard was a supernova of creative energy, he burst into the world with something unique and powerful. There are very few writers who can claim to have created a genre, but he did. And, poignantly, he did it alone, in a small town where he was considered a freak, with almost no moral support or understanding, except from his pen pals, especially H.P. Lovecraft, who saw and cultivated Howard's unique creative spark.

Also: "Usually at the first introduction of a woman, there’s a long passage where the narrator tries to convey that she is extremely hot." Howard was a young man who had one girlfriend ever, and that was a chaste relationship. It is virtually certain he died a virgin. His writing about women is unmixed with any knowledge of real love or intimacy with a real women. It is adolescent dreaming of an ideal woman. And it is not just lust, it is the desire for companionship and loyalty. Belit returns from the dead to save Conan because of her invincible love for him. She is not just "hot" -- of course she is -- but Howard was dreaming of more than that, and that guileless romanticism is what makes those passages so moving.

One other detail. During the Depression, when people were starving, Howard was making a decent living off of his typewriter, which his neighbors in Cross Plains, Texas could hardly believe. His stories were popular and in demand in the pulp magazines where he published. He was a professional who bashed out the work and got paid for it.

Recommended: The Whole Wide World. 1996 film about the unlikely romance between Texas schoolteacher Novalyne Price and pulp writer Robert E. Howard. With Vincent D’Onofrio and Renée Zellweger. One of Zellweger’s greatest performances; she’s spoken about how connected she felt to Price and really leans into her Texas-ness in a way you don’t see in her better-known roles. Based on Price’s memoir.