This working-class writer has turned into a symbol of elitism

If a college student is interested in learning how to write fiction, they will often take a class called "Intro to Fiction" or "Intro to Creative Writing".

In this class they will usually be asked to submit a short story to the professor, and this story will in turn be evaluated both by the professor and the class in a collective discussion exercise called "workshopping".

Preparatory to writing this story, the student will often be assigned a number of exemplary texts: short fictions that are meant to teach them what a good story might look like. And, in my experience, one of these exemplary texts will quite frequently be a short story called "Cathedral" by Raymond Carver—the final story from his 1983 collection of the same name.

This story is narrated by a married man whose wife is expecting a visit from a friend. A male friend. A friend who happens to be blind.

He was no one I knew. And his being blind bothered me. My idea of blindness came from the movies. In the movies, the blind moved slowly and never laughed. Sometimes they were led by seeing eye dogs. A blind man in my house was not something I looked forward to.

The blind man comes over, and they spend some time chatting. Then they all smoke marijuana, and the wife passes out. The narrator and the blind man start watching a documentary on TV—a documentary about medieval cathedrals. The blind man asks the narrator to describe the cathedrals, but the narrator can't do it—he doesn't really have the words. So instead they engage in a collective drawing exercise, where the blind man puts his hand over the narrator's, and the narrator attempts to draw his cathedral.

The meaning of the story is somewhat clear. The narrator can see the cathedral, but he can't really see it—he can't experience its essence. Paradoxically, it's only by closing his eyes and engaging in this collective exercise that he's able to experience the soaring quality that defines the cathedral experience.

The story ends:

My eyes were still closed. I was in my house. I knew that. But I didn’t feel like I was inside anything.

"It's really something," I said.

I would say this story is a good model for what the typical American literary story is trying to achieve. The story has very little overt conflict and nothing in the way of stakes. Nobody will be hurt at the end of this story. Nobody is even going to get divorced. But something is submerged here, some hurt or absence in the narrator, and somehow by the end of the story that thing is brought out into the light.

Why are we talking about Raymond Carver?

About two weeks ago, Alex Perez wrote a post on Substack telling literary men that they really ought to read Raymond Carver (“Hey, what you should do, if you want to get hip to the American literary tradition, is read the short stories of my guy Ray Carver”).

I was extremely impressed by the way literary Twitter responded to this post: many people had a visceral, negative reaction to Carver's name.

I attribute this reaction to Carver's odd position in American letters. Carver simultaneously represents elitism and the working-class. He is a writer who was nurtured by elite institutions: the Iowa Writer's Workshop, Stanford, Esquire, Knopf, The New Yorker. And he's a writer whose memory is kept alive because he is frequently assigned in college creative writing classes. At the same time, he himself was from a working-class background (his father was a sawmill worker and Raymond worked for a time too in lumber camps), and his characters often have a down-and-out quality, even if they're usually not explicitly working-class.

I also find that within the MFA world, Raymond Carver tends to be championed by a cadre of professors who really value the knowledge that is preserved by these institutions—the knowledge of how to write good literary fiction—and they feel that this knowledge is under threat in various ways, usually by some democratizing force that is trying to 'dumb down' literature.

Personally, I have a lot of respect for this viewpoint.1 When I was doing my MFA, I generally got along best with the kind of professor who really liked Raymond Carver, and I tended to get along less well with the kind of professor who tried to be hip and current.

In any case, because of these associations Raymond Carver's name carries a lot of baggage—probably much more so than any other American short story writer (besides perhaps Hemingway).

Indeed, because of all this baggage, I was passively quite well-disposed to Carver. This kind of old-guard professor might have narrow tastes, but whatever they enjoy is usually very good.

However, although Raymond Carver is one of those writers that I felt like I'd read, in actual fact, I had not read a book by him—I'd only read the two or three stories of his that get anthologized and assigned in class.

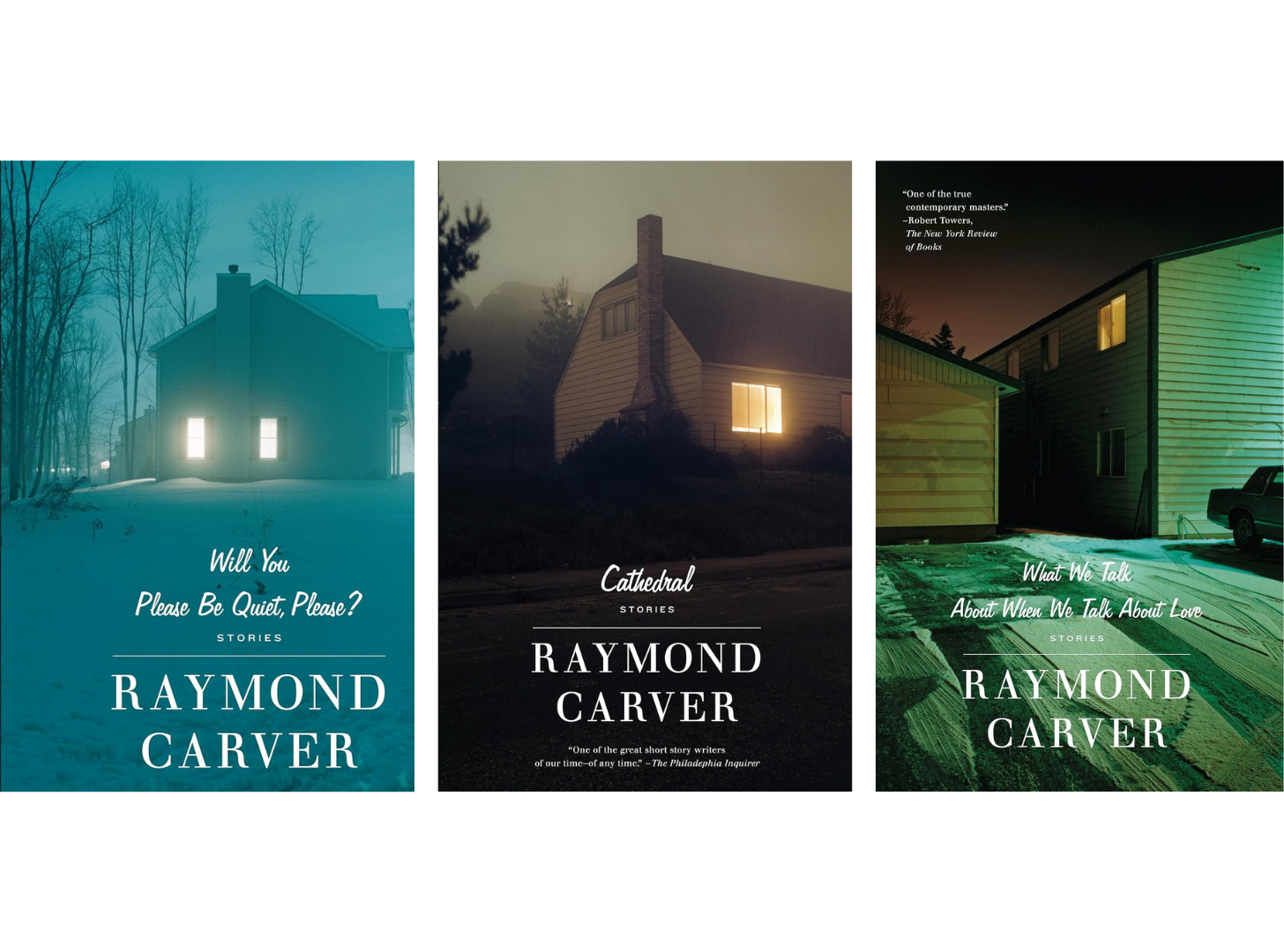

That’s why I decided to read Carver’s first three fiction collections, which comprise the vast majority of the stories he published in his lifetime. With Carver, we also have this very bizarre situation where there exists a book of alternate versions of the stories in his second collection, and I've read many of these alternate versions as well.

These stories are beyond mysterious

Two terms tend to get paired with Carver's name: "K-mart realism" and "minimalism". As always, with literary terms, these aren't necessarily words that Carver used to describe his own work. Nor do they mark Carver as belonging to some coherent movement. Instead, they're tendencies that critics identified in his work, which they linked to broader tendencies that were common in other literary works at the time (the 1970s and 1980s).

"K-Mart realism" is the less coherent of these terms. K-Mart is a now-bankrupt department store, a competitor to Wal-Mart. It's difficult to track down what "K-Mart realism" entails, but according to George Saunders, work that was described in this manner was being "praised for its frank, unabashed inclusion of elements then supposedly unusual in American literary fiction—television, brand names, pop culture, apartment complexes, malls, etc."

This would not be a good description of Carver's stories, which are generally not about buying things or consumption, and which rarely feature any of the above elements (including apartments!). However, the stories do seem, to some extent, to be about the kinds of lower-middle-class people who might shop at K-Mart.

Generally speaking, the characters in Carver's stories don't have clear occupations. When they do, they tend to be teachers or salesmen. There's one postal worker, and I can recall two motel managers and several men whose wives are waitresses. Two stories ("Feathers" and "Tell The Women We're Going") feature characters who seem to work in factories, but their work is not a major part of the story. Several stories are about men who've lost their jobs or are otherwise out of work. One story, "Vitamins", is about a woman who's in some kind of MLM where she sells vitamins.

But most of his stories are not specific about the characters' occupation or class status. And that's because of the second term associated with Carver: "minimalism".

I've often heard that Carver's writing was an example of "minimalism"—telling a story while describing only the barest minimum of visual detail, character motivations, and backstory—but I'd somewhat discounted that idea, because I'd read his most famous story: "Cathedral". And this story is not particularly minimal. The narrator of this story not only describes his wife's history extensively (including a description of her marriage to her ex-husband, an Army officer), but he also describes his own thoughts and motivations in a fair amount of depth, at least to the extent he's able.

What I hadn't grasped was that "Cathedral" was from Carver's third collection. And that the stories in Carver’s second collection, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, are really what gave rise to the ‘minimalist’ descriptor.

For these stories, that description is very accurate. These stories are so stripped down, they are beyond mysterious.

In these stories, you get virtually no description of the character's lives except what is necessary to establish their relationships to each other. For instance, in the first story, "Why Don't You Dance?", a man has moved his bedroom furniute to the front yard:

In the kitchen, he poured another drink and looked at the bedroom suite in his front yard. The mattress was stripped and the candy-striped sheets lay beside two pillows on the chiffonier. Except for that, things looked much the way they had in the bedroom: nightstand and reading lamp on his side of the bed, nightstand and reading lamp on her side.

His side, her side.

As we read the story, it becomes clear that this is a yard sale. It seems obvious that this man's wife has left him, so he's selling all their stuff. A young couple come to look at the garage sell, and he gives them whiskey, plays a record (he's run an extension cord out to his front yard), dances with the girl.

The story ends:

Weeks later, she said: “The guy was about middle-aged. All his things right there in his yard. No lie. We got real pissed and danced. In the driveway. Oh, my God. Don’t laugh. He played us these records. Look at this record-player. The old guy gave it to us. And all these crappy records. Will you look at this shit?” She kept talking. She told everyone.

There was more to it, and she was trying to get it talked out. After a time, she quit trying.

This is a fantastic story. It is so good! Can you imagine? This was the first Raymond Carver story I'd read ever since reading "Cathedral" and a few other stories ten years ago during my MFA.

And that's sort of what the stories in this collection are like. There is a lonely person. They encounter someone else. They engage in some kind of mysterious, emotionally-fraught activity. And then the story just ends.

In "Viewfinder", the lonely man is at home when he encounters a door-to-door salesman who tries to sell people pictures of their homes. The man gets the salesman to take pictures of him all around the house, and the implication is that the man wants to use these pictures to entice his family to come back.

In "Mr. Coffee and Mr. Fixit", a man goes to stay with his mom because his wife is having an affair. But the mom is also kissing some guy. The man goes home and his wife makes him coffee. The story closes with an ambiguous statement he makes to his wife:

“Honey,” I said to Myrna the night she came home. “Let’s hug awhile and then you fix us a real nice supper.”

Myrna said, “Wash your hands.”

That's the end of the story! "Wash your hands." The final line of the story. That is pretty bold.

Like, you're not really supposed to end stories this way. Even today, if I posted a story and that was the final line, you, my readers, would say "What the fuck? Where did the rest of the story go?"

"Gazebo" is the most straightforward story in the collection. A guy and a girl are motel managers, and they're trying to make good, but the guy has an affair with one of the maids, and both the guy and the girl start drinking heavily and neglecting their job—the girl tells a story about an old couple they met once on a drive. And they both realize they'll never be like that couple.

In Raymond Carver’s fictions, there are often these stories or anecdotes that the characters tell each other. Sometimes their interlocutors understand their meaning, and sometimes they don't, but usually the reader kind of understands what they're getting at.

Some of these stories are way too mysterious. For instance, in "I Could See The Smallest Things", the first-person narrator, a woman, wakes up in the middle of the night, goes outside and has a chat with her neighbor, Cliff. Her husband has been having a feud with this neighbor, and they don't really talk to him anymore. But Cliff is outside, pouring bleach on these pale white slugs. Cliff and the woman have a chat. Then she goes inside, and her last thought is that she's left the gate unlocked.

I did not understand this story at all.

Luckily, for the stories in this collection, there exist alternate versions. After Carver died, his widow, Tess Gallagher, published a collection called Beginners. These consist of the seventeen stories in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, but the stories are all quite different from the first-published versions: they're dramatically expanded, with much more description and backstory.

In other words, these are non-minimalist versions of the stories.

In the Beginners version of this story, we learn that Cliff has an albino son who's always sick, which puts his eradicating the pale white slugs in a totally different light. The story also ends with the woman waking up her husband and trying to tell him that something in her life needs to change, because she's not happy.

This version is completely comprehensible. Not mysterious at all.

But very few of the stories in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love are as incomprehensible as the slugs story. For most of them, you don't need recourse to the expanded versions.

The only other story that really made no sense to me was "The Calm", in which a man in a barbershop tells a story about a hunting trip, and then everyone gets mad at him. I had no idea why they were mad.

But when I read the expanded version, I realized they were mad because he'd gut-shot this deer and left it to die slowly instead of chasing it down and killing it quick. This is a piece of hunting etiquette I did not know about, and the expanded version had a line that clarified the fact that there was some implicit rule here.

The title story of this collection, which is also frequently anthologized (and which I'd read before), is one of the longest and least-mysterious stories in the collection. "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love" is about two couples who've gotten together, and they're sitting around the kitchen table drinking, and they start talking about the nature of love. And one guy, Mel, describes his wife's ex, and how this guy was a psycho who threatened to kill Mel and his wife, Terri. And they debate whether that psychotic attachment to Terri really constitutes love.

And as they're debating, it becomes clear that all these people are divorced. They're all on their second marriage. They all had first loves that they thought, at the time, they truly loved. And now, with the second go-around, they hope it's love, they hope it'll work, but...they don't know. They can't say for certain if they understand what love is.

Excuse me, did you say there's an expanded version of these stories?

Okay, so I've been writing about Carver's second collection, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. This collection came out in 1981, and it really made Carver's reputation. This collection was released by Knopf, where it was edited by Gordon Lish, who'd previously been the fiction editor for the magazine, Esquire.

Carver died in 1988.

Then, in 1998, ten years after his death, it came to light that Lish had heavily, heavily edited Carver's manuscript before publication.

This was something that people sort of knew beforehand, because Lish had been telling people for years that actually Raymond Carver's genius was Lish's creation. That Lish was just as much responsible for the greatness of these stories as Carver was.

But people generally didn't believe it, because people often say that kind of stuff about a genius (for instance, Truman Capote apparently claimed that he'd really written To Kill A Mockingbird). But then in 1998, a journalist decided to go and see for himself. Lish had sold his Carver papers to a university library, and this journalist, DT Max, went and examined them:

What I found there, when I began looking at the manuscripts of stories like ''Fat'' and ''Tell the Women We're Going,'' were pages full of editorial marks — strikeouts, additions and marginal comments in Lish's sprawling handwriting. It looked as if a temperamental 7-year-old had somehow got hold of the stories. As I was reading, one of the archivists came over. I thought she was going to reprimand me for some violation of the library rules. But that wasn't why she was there. She wanted to talk about Carver. ''I started reading the folders,'' she said, ''but then I stopped when I saw what was in there.''

This ignited a firestorm of controversy. People wanted to know, was Carver the genius? Or had he been created by Gordon Lish?

The level of editing went way beyond what is typical in these cases:

In the case of Carver's 1981 collection, ''What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,'' Lish cut about half the original words and rewrote 10 of the 13 endings.

Personally, I've published four books with traditional presses and about 60 stories in various literary periodicals. All of them were edited, but I've never had an editor rewrite the ending to any of my stories! That is wild! It is insane! That kind of thing simply does not happen.

Except, in Carver's case, it did.

Lish and Carver's relationship began when Lish was at Esquire, where he published some of Carver's stories (giving them this treatment), continued at McGraw-Hill, where he published Carver's first collection, and came to its climax at Knopf, where Lish performed surgery on this second collection.

At some point, shortly before this collection's publication, Carver wrote a despairing letter, trying to get Lish to withdraw the book—Carver was embarrassed because many of the stories had been published previously or circulated to his friends, and he knew people would wonder at how much they'd been changed before publication.

He had a love/hate relationship with Lish's editing. He sometimes accepted that the stories were better afterward, but with his third collection, Cathedral, he pushed back heavily and didn't allow Lish the same leeway. And what's why Cathedral appears to be written in an entirely different style from his previous work—more free-wheeling, discursive, with much more backstory and visual detail.

Several people have asked me: in the cases where we have two versions of these stories, which version is better?

Carver's could write pretty well on his own!

This question, I think, misses the heart of the matter, which is that the worldview of the two collections is entirely different. What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is so cold. These characters lead bleak, empty lives, devoid of connection, and the stories usually end on a moment of disconnection or alienation.

The stories in the manuscript version, Beginners, are quite different. For instance, remember that story that ended with “Wash your hands”? In the Beginners version, that story continues for another page! The wife makes a bed for her husband, and she discusses his mom’s love life with him, and she starts talking about how her husband really ought to do something for himself. You realize it’s really his alcoholism that’s driving them apart, not her affair, and you have hope that maybe something good will happen for these two!

Similarly, in the slugs story, which originally ends with the wife remembering she’d left the gate open, now it ends with her talking to her husband about her feelings, and she thinks, “Just so many words, you might think. But I felt better for them.”

And this difference is replicated across virtually every story. In most cases, the Beginners ending is much warmer and more hopeful than the one that actually got published.

And that more-hopeful worldview is what we tend to see in Carver's third collection, Cathedral. This collection was also very well-received when it came out, and it was nominated for the Pulitzer. The stories in Cathedral just tend to be much warmer. For instance, the first story, “Feathers”, is about one couple visiting another couple. The first couple is childless, and when they see the second couple's baby, they're very struck by the nice, warm wonderful life the second couple has built, so they go home and try to get pregnant themselves.

It doesn't work out that well. As the narrator puts it:

The truth is, my kid has a conniving streak in him. But I don’t talk about it. Not even with his mother. Especially her. She and I talk less and less as it is. Mostly it’s just the TV. But I remember that night. I recall the way the peacock picked up its gray feet and inched around the table. And then my friend and his wife saying goodnight to us on the porch. Olla giving Fran some peacock feathers to take home. I remember all of us shaking hands, hugging each other, saying things. In the car, Fran sat close to me as we drove away. She kept her hand on my leg. We drove home like that from my friend’s house.

There's still that coldness and loneliness, but there's also a moment of hope. He can remember that feeling of being excited about life.

In "Careful", a husband is separated from his wife, but he goes back to her when he has an earache, and she rustles around the house looking for things to put in his ear to somehow relieve the pain. The story ends: "Judging from the angle of sunlight, and the shadows that had entered the room, he guessed it was about three o’clock."

It's not morning, but it's not midnight either. There's still some time left for them.

Oftentimes the stories are sad, but there's usually a moment of genuine human connection in them. For instance, in "Fever", a man's wife has left him, and he's desperate to find a babysitter. Calling long-distance, his wife recommends a woman she knows, an old lady, who comes over and puts his life into order, giving him breathing space, before finally leaving, because she and her husband have decided to retire to their son's farm.

In "The Bridle", a motel manager interacts a down-and-out couple who've rented a room. The husband is depressed, doesn't really leave the room. The wife works as a waitress nearby. The motel manager does the wife's hair, and they're initially friendly, but then they grow distance. When the couple leaves, the motel manager understands:

“Thanks,” I say out loud. Wherever she’s going, I wish her luck. “Good luck, Betty.”

When people talk about Carver, they always compare the draft versions of his stories to the ones edited by Lish, and they usually conclude the Lish versions are better. There was obviously something very fertile in their collaboration.

But what Carver was able to do on his own, in his subsequent collection, was also very good. The finished stories in Cathedral do not feel as baggy or expansive as the draft stories in Beginners. They feel like Carver has gained a lot of confidence, and he has some new vision for what he wants to accomplish with his stories. They feel like Carver is finally editing himself and articulating some vision for what he wants his finished stories to look like.

Now the broader question is...would Carver be famous today if all we had from him was Cathedral? Well...probably not. The stories that were edited by Lish, the stories in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, are so eerie and so strange, so different from other stories, that it's no surprise they made an impact. The stories in Cathedral don't immediately strike one, in the same way, as being unique. If there's a reason I'm reading Carver now and not, say, Frederic Barthelme (a contemporary who was also said to practice "K-Mart Realism"), it's probably because of the stories in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. But that doesn’t mean Cathedral Carver is bad, just that he might not be that much better than other great, highly-acclaimed late 20th-century story writers.

What about the working class people?

Okay, but this whole post has been about style. And meanwhile, I'm reading Carver because I’ve been told he’s got insight into two groups: working-class people and men. Is that actually true?

I don't know...I feel like Carver is undeniably from a working-class background, but he was working within an elite context, and he was writing for a largely middle-class audience. As a result, most of his stories have the social class filed-off. The characters might be working-class, might be lower-middle-class, might be middle-class, might even be upper-class. When they have jobs, it's often very ambiguous. For instance, the character in "Sacks" is a textbook salesman. Is he some down-and-out salesman going door to door, going broke peddling Encyclopedia Britannica? Or is he selling textbooks to school districts, making a decent living. We don't really know, but I suspect he's more like the latter, because he's flying a lot for business trips.

In some cases, the un-edited versions of the stories make it very clear that the characters' are better-off than the edited version might suggest. For instance, the story "The Bath" doesn't give economic details about the family, but in the un-edited version, "A Small, Good Place", we're told the father is a partner in an investment firm.

Even when characters have a well-described job, as with characters who are teachers, motel managers, postal carriers, they often seem to have a more-or-less middle-class lifestyle.

In this New York Times article, D.T. Max says that Carver's collections "are mostly about the working poor — unemployed salesmen, waitresses, motel managers — in the midst of disheartening lives."

This is not really true. Some of the stories are about "the working poor", but those stories are a minority. Most of the characters are believably middle-class. Some are wealthy. Even in cases where the characters are down-and-out, it's often due to a lay-off, alcoholism, or divorce, not because the characters weren't able to make money. Obviously there is a lack of social and cultural capital implied in the fact that you've been knocked so low by alcoholism, but it's only implied by the circumstances—there is usually not enough detail to accurately assess the characters’ class status.

The stories also don't have a strong sense of place. Some of them are explicitly set in small towns in Northern California (Eureka and Arcata come up several times). Two stories that I read ("The Compartment" and "Everything Stuck To Him") are set in Europe, and one story ("Put Yourself In My Shoes") seems to be in an urban environment (perhaps Palo Alto or San Jose, where Carver spent a lot of time). But mostly the stories feel like they're in some generic suburbia or small town.

I agree that there is a lonely, bereft, precarious, down-and-out quality to many of these characters, but with most of them you can't put your finger on anything that's definitively marks them as working-class.

Okay, but what about the masculinity angle?

A striking thing I haven't mentioned is that a small minority of Carver’s male characters are truly unhinged. For instance, in "Tell The Women We're Going", the two main characters pursue two women they see on the side of the road, with tragic consequences. And in "They're Not Your Husband", a man bullies his wife into losing weight, then goes to the diner where she works and tries to convince other men to objectify her.

There's a few stories like that. I tended to really enjoy those stories, although they're a minor part of the ouevre (Carver also tells a number of stories, quite ably, from a female viewpoint).

I would say that many men in these stories have been left by their wives and are often haunted by the loss of their families—this is the main driver for at least ten of the seventeen stories in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.

On that level, I don't know how relatable the stories would actually be for the contemporary man. That book was published in 1981, the year that American divorce rates peaked. Whereas in 2025, age at marriage is up, and divorce rates are down—the contemporary man spends much less of his life married, and he's less likely to get divorced if he does get married.

But of course not everything needs to be relatable. As a driver of tension, it's a great device. And there is a lot of pathos in how lost and helpless and angry these men seem to be.

There's a real darkness at the core of What We Talk About..., a sense of violence that simmers just underneath many of these stories. Although it only occasionally breaks out into the open, that violence really haunted my whole experience of reading these stories.

And I mean that as a compliment!

Can students learn to write like this?

As I said, in 2025, the memory of Raymond Carver is mostly kept alive by a certain subset of creative-writing academia. He matriculated at the Iowa Writer's Workshop (though he never graduated) and for a time was a creative-writing professor at Syracuse. His early stories were often published at small literary journals which were sometimes associated with universities, and his was friends were with other writers, like Tobias Wolff and Richard, who also taught in creative writing workshops.

When young writers attempt to write their first stories, they are explicitly given Raymond Carver as a model. And at least in the graduate program that I attended, his was a model that was still present in the minds of some of the male writers who were at that workshop with me.

Over the course of my life, I've now read many American short stories that were basically Carver stories: someone is really sad, but you don't totally know why; they do some mysterious things; at the end, the reader is plunged into rhetorical ice-water—we realize the character’s life is even more abysmal, empty and hopeless than we had originally imagined.

It feels like a tradition that is somewhat played-out, just like many other traditions have gotten played out over the years. We understand this type of story too well. We've read it too many times. Even during Carver's lifetime, this story was extremely common. His (and Gordon Lish's) innovation was that they reduced this story to its most minimal constituent parts.

Anyone else who attempts to write stories on this model will need to make some similar innovations if they're going to impress me.

So what does that mean? Is it impossible to write new stories?

Well...no.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most stories were written on a much different model. You have a person, and they have a problem. They attempt to solve the problem. The tension comes from wondering whether or not they will solve it. In the end, they solve it in some unexpected way.

This is a form of story that is ever-green, albeit one that you'll find fairly difficult to publish in a traditional literary journal.

Where do I start with Raymond Carver?

Start with his second collection, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Then if you want to read a very different Carver, read his third collection, Cathedral. In his life, he also published a “Selected Stories”, which takes the best stories from all his collections. This compilation volume, Where I'm Calling From, is where most people would be tempted to start, I think. But I generally feel like "Selected" or "Collected" stories risk having kind of an unstructured or ramshackle feel, and in this case his second collection hangs together so well, and it's so cohesive, that I highly recommend starting with it instead.

The first collection, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?, is also quite good, and because Lish only edited a few of the stories in that collection, it has an odd mix of the two Carver styles.

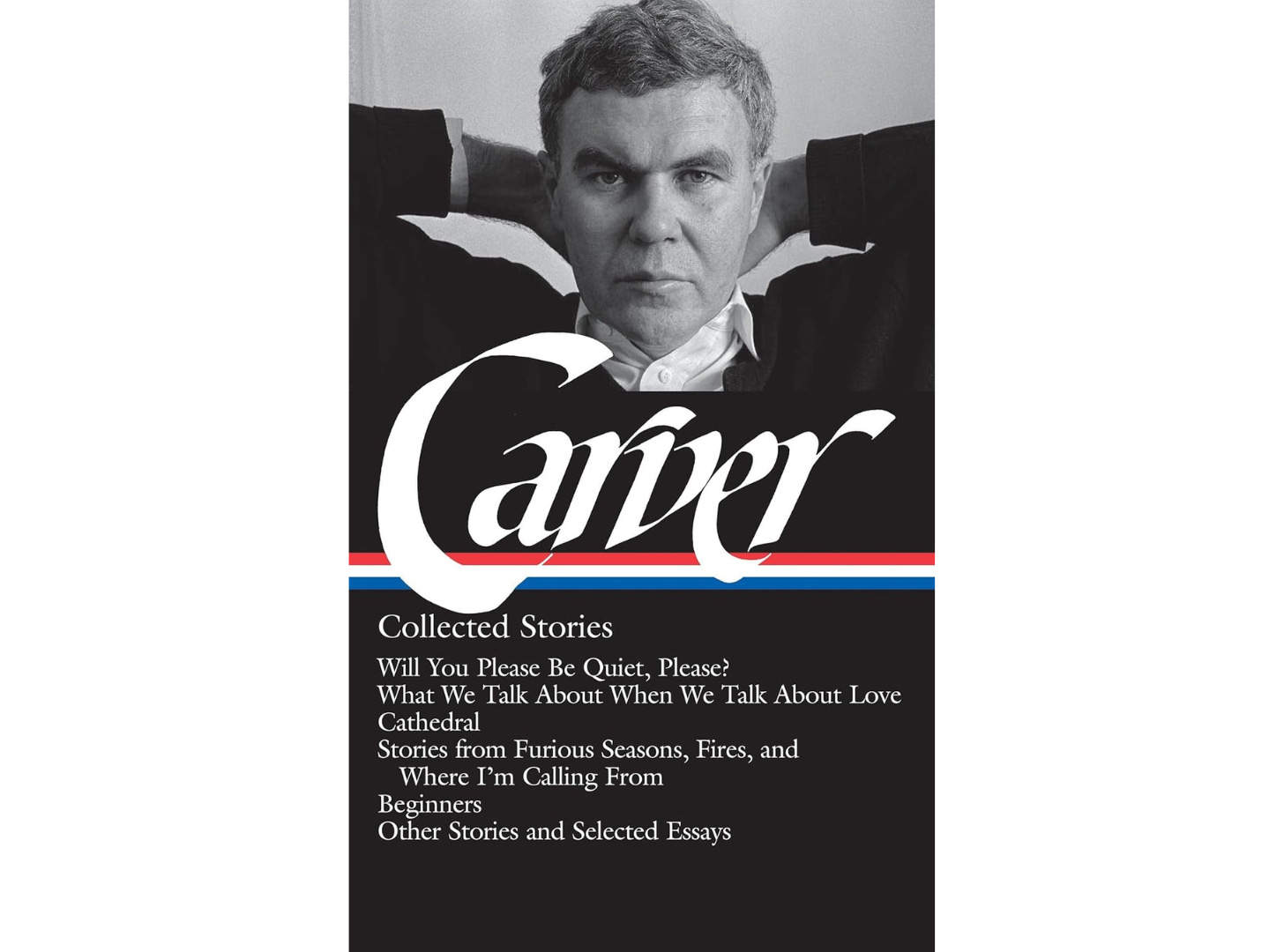

If you prefer to read paper books, I recommend getting the Library of America edition, which prints all his short fiction, including the manuscript versions from Beginners. If you prefer ebooks, unfortunately there is no ebook version of the LOA edition, but the others are available from Vintage Contemporaries.

I don’t necessarily agree that there is an external force trying to dumb down literature, but I do think that if a person is going to teach creative writing at a collegiate level, then they ought to believe in what they’re doing—they ought to think that they hold the keys to a body of knowledge that is worth preserving. And in this case that body of knowledge surely includes the work of Raymond Carver.

I think it's best to read them in order. "What We Talk About" can be kind of hard to read, so I wouldn't start with that one. They're all great. Lish is great, Carver is great. The abrupt, Lish-influenced ending of "The Bath" is brilliant. But "A Small Good Thing" is nice too. When you're done you can watch Robert Altman's "Short Cuts" which recycles the plots, but not the emotional texture.

Carver's stories are very Chekhovian. They are often about people who are stuck in a rut. The climax typically involves the reader (and sometimes the character) gaining knowledge about their situation. So it really wasn't new even when he was writing.

I think the need for formal innovation is exaggerated. Carver's stories still work just fine, as do Chekhov's. I do think stories that withhold can be a trap for writers, because there's a temptation to withhold things you don't understand, and that typically leads to boring, vague stories.

It's crazy that this story of Carver and Lish isn't central to how everyone is educated about his influence on American literature. I'd never heard about it, and I teach the anthology short stories, I took multiple American literature classes in college that featured a lot of work from the 20th century, etc. It seems like in your description of Carver's original work, he's much more open to getting into the weeds of what's going on in the world around him, but Lish (maybe because of his class background) understands that he'll have more influence on writers at elite institutions if he's mysterious. I wonder if that's because it doesn't exactly fit into a neat box around identity, politics, or literary movements. By 1981, Carver's work is probably looked as pretty conservative in every sense---it's not engaging with race or gender or sexuality in an explicit way, it doesn't engage with postmodernism, it comes out of the most elite and typical place it could emerge from (IWW). It's the opposite of literary writers like Donald Barthelme or Lorrie Moore or Jamaica Kincaid or Lydia Davis, and obviously there's a million "genre" short story writers in science fiction or fantasy that Carver's explicitly not interacting with either. But in this conflict or collaboration with Lish, there's a sense that the two of them are trying to carve out a space for "craft" in some sort of way, and they're wildly successful in most senses, especially given Carver's continued influence.