A writer's career can be rooted in real power or in fake power. Real power is better.

A few weeks ago, Compact published an article—“The Vanishing White Male Writer”—about how there’s no white men writing literary fiction anymore.

I found this article insanely funny, because of the following graf:

The more thoughtful pieces on this subject tend to frame the issue as a crisis of literary masculinity, the inevitable consequence of an insular, female-dominated publishing world. All true, to a point. But while there are no male Sally Rooneys or Ottessa Moshfeghs or Emma Clines—there are no white Tommy Oranges or Tao Lins or Tony Tulathimuttes.

After years of masculinity discourse, the sticking point is being redefined. Now it’s not just men who are missing, it’s white men.

It is wild. It is so funny.

Because…this maneuver is quite familiar. This is just how identity politics works. Your demands for representation get finer- and finer-grained, because ultimately the demand isn't about masculinity, it's about literary spoils—getting book deals for people like yourself.

Let me give you an example from my own experience. Ten years ago, in 2014, YA writers started a hashtag campaign called #WeNeedDiverseBooks. They wanted books with more diverse protagonists. The publishing industry duly responded by buying books with more diverse protagonists. But many of these books were written by white women. An example was Simon Vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda, one of the first breakout queer YA romances. It was written by Becky Albertalli, someone who was not a gay male. As a result, YA authors began another hashtag campaign, called #OwnVoices. Diverse protagonists weren’t good enough. Now you needed protagonists written by authors who had the same positionality as their characters.

This continued, with the demands getting more and more specific. Eventually there were a fair number of YA trans books, but most of them were by and about transmasculine characters, so transfeminine authors groused, saying we needed more representation—at one point there was a controversy because a YA trans anthology didn’t have any trans-feminine voices.

You know how it is. You were all there. But…I do feel like a lot of the people engaging in male-writer discourse actually weren’t there. They didn’t participate in identity politics during the 2014 through 2024 period, so this is their first time! And it’s so funny to see them go through all the identity politics beats all over again.

Personally I am not offended by white male identity politics in the cultural sphere. White men are something like 35 percent of the country, so they should probably be represented in all the major art forms, no? But…I do see some problems.

As many people have noted, white men are well-represented in every sphere where there are actually white male consumers. White men like to listen to podcasts, watch movies, watch TV shows, and play video games. They also like to read crime novels, military thrillers, and nonfiction. As a result, all these fields have plenty of white male representation.

In contrast, white men don’t particularly like to read literary fiction, and that’s the major reason white male representation is relatively low amongst the ranks of the most successful literary writers.

That’s not necessarily a barrier to further representation; it just means that a call for white male representation is, fundamentally, a demand on the attention of female readers.

Trans women performed this same maneuver

In this, it’s the same as when trans women wanted recognition. We wanted people to pay attention to us, and to think about us. And to a large extent, we succeeded. Ten years ago, there were no transfeminine authors with book deals at Big Five imprints. This year, in contrast, a number of novels by trans women have already come out out from big imprints. Nicola Dinan’s second novel came out earlier this year. So did Torrey Peters’ novella collection Stag Dance. Jennifer Finney Boylan has a memoir out. Andrea Long Chu’s essay is out this month. Jamie Hood has one of these memoir / cultural criticism coming out. Denne Michele Norris has a novel out in May. Those were all from large presses. When it comes to smaller, but still decent-sized presses: Emily St. James Woodworking came out a week ago, and Jeanne Thornton’s A/S/L dropped just last week. That’s pretty good. That’s only in the first half of this year!

Most of these books are downstream of the success in 2021 of Torrey Peters’ novel Detransition, Baby. That novel was both a commercial success (selling at least 500,000 copies) and critical success—it was reviewed well and was nominated for the UK’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. That is by far the most successful novel by a trans woman. The next most successful is probably Ryka Aoki’s 2021 sci-fi novel, Light From Uncommon Stars, which seems to have sold in the 200k range. There’s another 2022 sci-fi novel, Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt, that’s sold over 100k copies. After that, I don’t think any book by a trans woman has cracked 100k. The closest is probably Nicola Dinan’s first novel, Bellies, which has, I think, sold between 50,000 and 100,000 copies.1

The problem with identity politics is that it can succeed up to a point. Trans women convinced cis-gendered women to pay attention to us. But…how many books are you really going to read out of obligation? Probably just one, if that. Most people who’ve read Detransition, Baby didn’t feel a strong need to read another book by a trans woman. They didn’t even feel a need to read Torrey Peters’ second book, Stag Dance (which is excellent, by the way)—Stag Dance has been out for a month and seems to be garnering a fairly muted reaction.

The white men will not have it so easy

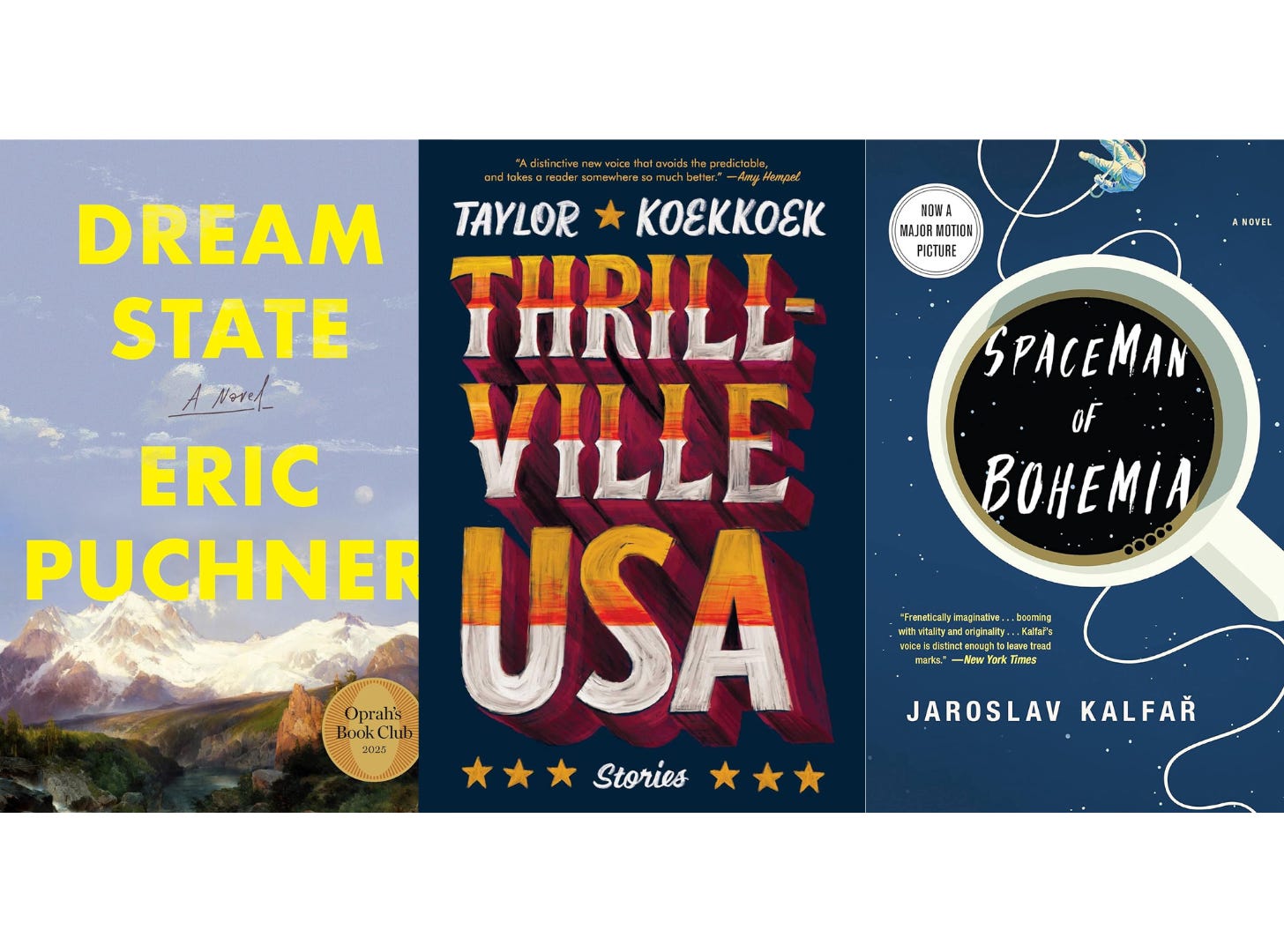

With white men, the problem is that white men do get published, but the resulting books tend not to succeed with readers. One graduate of my MFA program got a six-figure deal for his story collection, which flopped. I know about another guy who got more than $500,000 for his novel, which also flopped (and then got turned into a Netflix movie that also flopped!) Right at this very moment, a former professor of mine has a novel out that’s an Oprah pick! You have not heard of any of these writers or their books, most likely, because…their work just didn’t arouse any excitement. My professor’s novel literally hit the NYT bestseller list in the same month as the Vanishing White Male Writer article, but it didn’t even merit a mention in the article.2 And rightfully so, because…yes, the publisher invested a lot in it. But it doesn’t really seem to be having a cultural impact.

White men often get published. And when the books come out, they’re often reviewed well! But…readers don't actually get excited about them.

And there’s a reason for that. It’s because most readers are women. And most women don’t necessarily feel obligated to inform themselves about the inner life of white men.

So…the purpose of this white male identity politics is to create that obligation. To make women feel like they’re uninformed if they’re not reading contemporary white men.

I have my doubts about whether it’s actually possible to create this kind of obligation. My understanding is that the central problem of the white male writer is that you’re raised with some mythology of yourself as a powerful person, but at some point you realize you’re actually weak and impotent. Yet you’re in a culture where in order to succeed, both professionally and personally, you need to project power.3 So you end up feeling weak and insecure. White male writers would like to convey this struggle in fiction, but…fiction is subject to the same problem. Female readers are repelled by men who seem pathetic, and if your protagonist is too self-loathing or weak, then women won’t want to read them.

In this, contemporary writers aren’t uniquely cursed. All white male writers have faced the same struggle. This is literally the central struggle in Knausgaard for instance. That’s why he spends the last book ruminating on Hitler. Because Hitler was the ultimate man, completely self-created, and yet he was also the ultimate monster. Knausgaard saw both the good and bad sides of himself in Hitler.

Writers generally succeed first with their core constituency

Okay, but Knausgaard exists. So do Updike, Roth, Mailer, Franzen, DFW, Chabon, Lethem, Eggers, etc. All of these people dealt with the same crisis of masculinity. All of them made careers. All of them have plenty of female fans. So why should it be any harder for a contemporary writer than it was for them?

Well…in my experience, great writers tend to succeed first with their core constituency and then build from there. All of these writers succeeded first because other men loved their work. That core male readership provided them with a base from which to grow their audience.

Contemporary male writers don’t really have that male audience to appeal to. Contemporary male writers instead need to succeed by pleasing a female audience. And that’s tough. It puts you on shaky ground.

I recently read an article by Glenn Loury where he came out against affirmative action. As he puts it:

Putting my concerns plainly, there is "fake power" — deriving from one's ability to protest and to issue demands if one is not "included"; and there is "real power", deriving from having attained mastery over the technical materials at hand. I — Glenn Loury — prefer to root the standing of black Americans’, over the longer haul, in "real power" not "fake power".

I sometimes feel similarly about a literary career that's rooted in the politics of representation. If you’re writing about a group, but not being read primarily by that group, then it’s quite hard to write authentically.

This is hard even for trans people. There are so many trans memoirs published, often multiple of these books each year, and they never really succeed, because…they have no real constituency. Trans people don’t read these memoirs because they’re all trans 101, explaining stuff that we already know. We all transitioned. We have our own transition drama—we have the transition drama of our friends—we don’t necessarily need to read about some celebrity’s experience. I have no doubt it’s possible to write a trans memoir that would appeal to trans people, but it’d need to complicate the coming-out / transitioning story in ways that would probably make it less accessible to cis-gendered people.

Meanwhile, cis-gendered people have also heard and seen a lot of trans stories at this point. And their level of interest in further exploring the trans experience is quite limited. As a result, they don’t necessarily buy these books either. But because these memoirs are written for a cis audience that doesn’t exist, they’re unable to appeal to the trans audience.

With white male books, the problem is even harder, because the reading public is composed of women. And many of these women aren’t just indifferent to masculine stories, they’re somewhat hostile to them. So the book needs to be written in a way that bypasses or soothes that hostility (this is what the latter half of the Vanishing White Male Writer piece is about), but then this handicaps the book when it comes to pleasing the male audience (which, admittedly, is not very large).

The solution is, honestly, to be like John Pistelli and ARX-Han and Caleb Caudell and Delicious Tacos and Alexander Sorondo. Self-publish. Whatever audience actually exists for these books—you publish for that audience.

This too is how trans writers started out. Two of the most successful trans woman writers, Gretchen Felker-Martin and Torrey Peters, got their start self-publishing their work for an audience of other trans women. Even to this day there’s a cottage industry of self-published books by trans women. Self-published authors like Alyson Greaves persist in their popularity even though trans woman writers have so much representation now at the big presses. And that’s because the trans books that come out from big presses don’t necessarily serve the actually-existing community of trans readers. Moreover, when trans writers genuinely target trans readers, then they can market to them in a much more granular way.

Self-publishing is depressing, but so is chasing mainstream attention

Last year, I realized that whatever success looked like as a trans writer, I was not achieving it, so I decided to pivot away and to put more into this Substack. In my newsletter, I've largely avoided discussion of my gender identity, and I think almost none of the characters in my tales have been trans.

People read my work because I write about stuff they care about: highbrow literature and the Great Books. I have derived some attention because I'm one of the few non-white people writing in this space, but honestly my posts about the Mahabharata are not necessarily a big driver of growth.

It’s been a relief to stop playing the diversity game. I'm glad that I got out. I think the broader lesson is that you need to build your own readership if you're going to feel truly good about being a writer in 2025. If you’re a trans writer who write for trans readers (like Alyson Greaves) or a male writer who writes mostly for other men, then you’re not really playing the diversity game at all, any more than, say, a Bulgarian writer is playing the diversity game when they publish in Bulgarian for a small, domestic audience.

That's what Glenn Loury means by comparing real power versus fake power. Real power comes when you provide genuine value to an audience that deeply desires what you're giving. Fake power comes when you're just being propped up by an institution that feels a need to meet some quota. With real power, you have fans for whom your voice is irreplaceable, whereas with fake power, you're just a box to tick and you can be replaced by any other authors with the same demographics.

I certainly believe there is also an audience of people out there who is genuinely interested in other viewpoints. Knausgaard exists, after all. His crazy Hitler book only came out in 2018 in America—not that long ago. There’s definitely some partial appetite even amongst female literary readers for an honest treatment of the white male experience. And I believe that institutions can elevate a certain voice and bring them to the attention of people who are actually looking to read something out of the ordinary. But when you orient your entire career around the idea that you’ll be picked by those in authority as the avatar of your identity group, it often feels quite hollow.

White male identity politics in literature is driven by anger. These men feel angry that they can’t reveal their true selves to women. And I sympathize with that anger and think it’s well-merited. But…what comes next? Yes, there’s always a hope that some writer will be a big enough genius that they can win over editors, critics, awards juries, etc. But this seems to be asking too much of any writer. No writer can ‘solve’ masculinity and create some perfect, appealing blend of power and insecurity that’ll please men and women alike.

But when you write for other people like yourself, there’s so much more freedom to maneuver. Suddenly you don’t need to write a perfect man; now you can just write a man who seems real and good. And, paradoxically, that freedom to be honest and genuine is what will allow writers to strive for true genius.

Every time I write something like this, I get responses that’re like, “Just tell your authentic story, write for yourself, don’t worry about who’ll read it.” But…I have many years of experience subjecting ‘my authentic story’ to readers who have never experienced the things I’m writing about. For instance, with my second YA novel, I felt very strongly that the queer boys in YA novels were too chaste! It was all hand-holding and yearning glances. There was no sex. It just didn’t seem at all true to the queer boy I once was. So I wrote boys who had sex and…it was a big turn-off to a readership that was mostly composed of girls. In fact everything about these characters was a turn-off to my readers.

In some other world, where I’d been writing to a readership of boys, I could’ve developed my style and continued writing about their sexuality in a way that seemed true to me. And perhaps, after a while, I could’ve achieved a level of mastery that made my characters persuasive even to female readers.

But because of the way the book performed, I didn’t get those extra chances. I sent around a YA proposal two years ago, from a queer male perspective, and editors weren’t interested. Too uncommercial, they said.

That’s what it means to have a career that’s not based in real power. It saps your ability to write with confidence and to develop your own approach to your subject matter.

I’m not following my own advice (I never do)

Of course…I don’t write for other trans people. This newsletter has some trans readers, but not many. The truth is that I spent ten years submitting my work to agents, editors, and readers who couldn’t really relate to it. They read it with interest, but not enthusiasm. And because I was so invested in trying to stimulate their enthusiasm, I didn’t engage much with my own community. I was very psychologically invested in the idea that I’d be one of the winners. That I’d be different from and better than other queer writers of color. That I’d write something uncompromising and universal. And as a result of that desire to go it alone, my work pleased nobody.

After giving up on being the voice of my generation, I could’ve tried to cultivate a trans readership, but…instead I began to aim for a certain level of universality. In this I’m like Ted Chiang: one of America’s most prominent Asian writers—I don’t think he’s ever written an Asian character, because race just would’ve gotten in the way and kept a part of his audience from empathizing with his characters.

For male writers, there’s limited benefit to getting that big book deal or big award. This idea that if you just write a beautiful-enough novel, then people will forget their preconceived notions about whiteness and masculinity—it’s absurd.

And giving up on the chance of being selected means you’ll find other ways to connect with people. For instance, I was talking to another trans woman once about history podcasts, and about how they’re almost all hosted by white men, and how they give off such a genuine, wholesome side of masculinity. These men almost always started these podcasts in their twenties, and if you listen long enough, you hear the man grow up, get older, gain confidence, find a wife, have their first child. It’s so heartwarming! These men are ineluctably masculine: they love the Byzantine Empire or Rome or Chinese History or what-have you, but the nature of their trade forces them to connect with people in a way that’s immediately quite disarming. Their will to power is constrained by their subject matter. I mean…I listen to one podcast where this guy has spent years talking about Napoleon. Literal years of his life. He is obsessed with Napoleon, just like Knausgaard was obsessed with Hitler—this podcaster’s obsession is powerful and fertile without being frightening.

Look, if I was a young white male writer I’d be gunning for that big ‘voice of my generation’ book deal. I know that’s what I’d do, because as a young queer writer that’s exactly what I did! At AWP I met plenty of queer writers who still want that deal. Some of them will get it, most won’t, and the ones who don’t get it will probably have longer careers than the ones who do. I expect this crop of white male writers to have similar struggles. Moreover, if the trans writers are anything to go by, the white writers who eventually prove to be the most commercially successful will be the ones who hone their product first by self-publishing it for a small clique of people who are truly invested in this form of fiction.

Unlike Glenn Loury, I find myself unable to turn against diversity politics. I don’t think that trans writers have suffered, as a class, from our increased career options. Yes, it’s true that many peoples’ creative abilities have probably been ruined by getting big book deals for underbaked books. But…most writers are ruined by something or other anyway, and being ruined by money seems better than being ruined by poverty or despair. For my own sake, however, I’m thankful to be finished with the diversity game, and I imagine many white male writers will look back in ten years and feel the same.

Elsewhere on the internet…

Daniel Oppenheimer and myself closed out our thoughts on anti-wokeness. It was a good discussion, but I was surprised that Daniel Oppenheimer thinks left-wing cultural spaces are still unable to tolerate dissent, and by the extent to which he was unwilling to really engage with left-wing ideas about race. As I told him:

It seems now we have this two-step where people, yourself included, simultaneously say woke ideas predominate in the cultural sphere and that these ideas are so clearly unconvincing that they're not even worth debating. The natural corollary of this belief is that the cultural sphere must be eliminated. You can't have it both ways. You can't argue that the cultural sphere is important, and that it's dominated by people with self-evidently false beliefs who are impenetrable to logic.

If those things are true, then the only way to recover the cultural sphere is to bring it into line by force. And that is exactly what Trump intends to do.

I estimate sales by multiplying the number of Goodreads ratings by 7x. This highly scientific method is one I developed by looking at my own Goodreads ratings and my sales figures—it holds up best for YA novels, because that’s a readership that uses Goodreads extensively. For literary fiction, it probably represents a significant under-count. Nonetheless, the figure is true-ish.

Any book that’s picked by Oprah is going to hit the NYT list, so that doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a lot of intrinsic interest in the title. In this case, it debuted at 12 and only stayed on the list for two weeks.

Caleb Caudell summarizes the difficulty of white male identity politics in his note on the topic.

I know it sounds sour to reactionary ears (I have a pair myself) but white men who want power and influence and wealth still do pretty well for themselves, if they have the stuff for it. They usually go into finance, politics, energy, sectors with high stakes. The competition is brutal, undoubtedly, but they hold their own, and not on account of concerns over representation and identity. Bemoan it all you like, but the fact that much wealth and power is still in hands of white men will make sympathy for novelists a hard sell. Representation in art works much like a tribal reservation, only now it’s not imposed, but desired and demanded. In fact, we know things aren’t all bad for white men specifically because they’re not prominent as authors right now. If they started winning literary prizes, then we’d be right to worry about them.

Click through to read in full, I found his thoughts on the topic quite interesting.

Great read. I experienced a version of this identity-based fake power cycle on a smaller scale a few years ago. I started submitting my short fiction for publication in a more focused way in 2020. I was writing quiet, literary stories that drew on my Korean family's history and spoke to the immigrant experience. When Asian representation and #StopAsianHate blew up in 2021, I thought (cynically): great, now is my time. They are going to open the floodgates to Asian American writers and I will ride this wave to literary stardom. And then... that didn't happen. I published a couple of stories in small literary journals. A handful of Asian Americans got book deals, mostly about intergenerational trauma and strong women. Quotas were met. Winners were chosen. Interest faded.

I also thought the Compact article was funny. At one point, he narrows the parameters even further to make some point about award nominees. Now, it's not just white male writers who are underrepresented-- but STRAIGHT white male writers! The gays don't count. I could feel the unspoken assumption lurking in the background. Straight, white, men-- you know, NORMAL people. Everyone else is a deviation.

I am a little torn because pretty much all of my favorite writers are white men. Also, full disclosure, I'm married to a white man. I'm sympathetic to the grievance. I think our society would be healthier and the culture more vibrant if more straight white men were engaged in reading and writing literature, and didn't feel shut out of those cultural spaces. But I'm not convinced that we need affirmative action for white male writers.

You talk about "the central problem of the white male writer" but then you describe your own struggle to publish stuff that authentically reflects your experience as a trans person. I think authentically expressing yourself is the central problem of every writer, or maybe every person.

It's interesting that girls were turned off by the depiction of sex in your YA novel. I tend to think we're going through a moral panic against male sexuality. It's all rather tiresome. You get the sense women have become very frightened of something they secretly desire. Sometimes I think the quantity of extreme sexuality available on the internet leads people to try to create a safe, sexless space elsewhere. But safe art is usually not very good.