Highbrow literature has acquired a fandom. To succeed, writers need to manage it.

Recently I hung out for a few hours with one of my readers: Arjun. This man, Arjun, is a twenty-three year old engineer who reads three literary newsletters: Woman of Letters, The Republic of Letters and The Metropolitan Review .

And Arjun had some questions about the contents of these newsletters. He asked me: "What is white male writer discourse? I am so baffled by this discourse. I hear all about these white male writer books, and I go to read them, thinking they will be something reactionary, but then they are not reactionary. They are just the same as all the other books!"

It was so funny. He had a series of jokes, all on this topic, about how baffled he is by lit-world discourse. This guy should be a stand-up comic.

Anyway Arjun was exaggerating his confusion somewhat for comic effect, but his essential point was that these three newsletters (Woman of Letters, The Republic of Letters, and The Metropolitan Review) often spend a lot of time reacting to perceived iniquities in the publishing industry. For instance, in a recent review of Emily St. James’s novel, Woodworking, I had a long preamble about how this novel was the kind of book that doesn’t get any critical attention.

I can easily imagine that Arjun might’ve found that post to be confusing. After all, he is reading several thousand words about this book, Woodworking. That constitutes critical attention—he is reading more about this book than he has probably read about any other work of fiction published this year.

I was so struck by Arjun’s critique that I tried to tell my friends about this guy: "To him, we are the literary world. He doesn't get why we're so angry, because to him we are this world."

But my literary friends honestly didn't get it. They somehow thought that Arjun doesn't read books, and that I was educating him about literature or something.

That's not what I am saying at all. Arjun reads books. I am sure the books he reads are very smart books. If I didn't exist, he would continue to read books and be perfectly fine.

Our literary culture has lost faith in ‘the general reader’

Since starting this newsletter, I have become very familiar with people like Arjun: intelligent people who read books and are interested in literature, but are not connected to lit-world discourse.

However, I find that, in practice, it is very difficult to convince the literary world that folks like Arjun actually exist. They believe readers exist, but they tend to think most readers are stupid and don’t like to read smart books. They think that readers of smart books are an endangered species, and that a critic’s primary role is to convince the readers of dumb books to read smart books instead.

But, recently, literary people have started to lose faith even in this rather-condescending goal. Nowadays, literary people have started to conceptualize reading itself as being an endangered activity—they believe that the general public’s actual ability to read has somehow been diminished by the rise of smartphones.

On one level, the amount of doom and gloom in the publishing industry is somewhat strange, given that book sales are doing okay. In fact, book sales rose during the pandemic and although they’ve fallen in the last few years, they’re still above pre-pandemic levels.

Nonetheless, if you talk to many literary people, they will insist that the novel is doomed. Why is this?

Well, there is certainly data that reading scores have gone down. But I would argue the much bigger impact on the publishing industry is that sales of newly-released books are way down. Which is to say, book sales are flat, but sales of newly-published books are down. In 2010, 54 percent of book sales were backlist (i.e. books that were published over a year ago). In 2024, that had risen to 70 percent. This trend has hit debut writers the hardest. That’s why debut novelists are having increasing difficulty ‘breaking out’ (i.e. achieving commercial success).

Personally, I’d argue this is a normal thing when you have an aging populace. The median age of the US in 1990 was 32, the median age in 2025 is 38. Old people prefer old things. We are an older country, so now older things are outselling newer things.1

This means that books as a whole are doing okay, even as the career prospects for writers have gotten much worse. There is a decoupling here. Going forward, it will be possible to have books and literature, without necessarily having writers.

Moreover, I would suspect that all of these trends hit the highbrow section of the industry much harder than they hit commercial fiction. That’s because commercial fiction provides a reliably satisfying product, while in literary fiction the quality tends to be much more variable. Moreover, literary fiction relies a lot on convincing the reader that reading this book will somehow improve them or make them a better person. But a book that was published fifty years ago is able to make a much better claim to being ‘important’ than any book that was just published this year.

In other words, it’s very difficult to say, about any literary book published this year, that it’s really superior to The Corrections. So…why not just read The Corrections instead?

People like Arjun are not highly attuned to new releases. They read what they like. Oftentimes these are older books, usually ones that've been recommended by friends. Word of mouth takes time to build. He might read a book published this year, but he'll probably read it five or ten years from now. He's not necessarily going out and buying it new, in hardback.

I talked to Arjun about this supposition, and he confirmed that the most recently-published work of literary fiction that he’s read was The Road, which was published in 2006.

Literary publishers have oversupplied the market

Seen in this light, the problem with the publishing industry is not a problem with our underlying society and it’s not a problem with the readership as a whole—it’s merely a problem of product-market fit.

What you have are a set of companies that are selling a product: newly-published literary fiction. And this product is not moving off the shelves. They are having a lot of trouble getting people interested in this product.

And one solution is for these companies to just publish fewer books.

But, each of these companies has built its business model around publishing new books. As a result, they employ many editors whose job it is to acquire new books from authors like myself. Each publishing company has its organizational processes set up to print and distribute a certain number of new books per year. These editors' job is to ship product, and in order to keep their jobs, they need to pretend like there is a strong demand for new books.

As a result, we have this situation where publishing companies are shipping truckloads of this product (literary fiction) in vastly larger quantities than people actually want.

But why does this lead to Arjun being confused by the strident tone of what he sees in my newsletter?

Everyone in this industry has become desperate

Well...there is a whole ecosystem that has built up around this product. There are graduate programs and summer conferences and continuing education classes that teach people to produce this product. There are residencies and fellowships that go to people who are good at producing this product. There are prizes that are awarded to people who are good at producing this product. There are fancy parties and reading series that are used to fete the best producers of this product, literary fiction.

And all of the people in this world are feeling the squeeze. They all understand, on some level, that their days are numbered. Each year the amount of energy in this ecosystem goes down. And people are desperate for some way of staving off the end.

The people in this ecosystem have a vested interest in conflating their own activity with "literature as a whole". So they don't think I am selling a particular product—new literary novels—for which the readership is dwindling. Instead they think, Nobody is interested in literature anymore. And, ironically, this coping strategy on their part is what has convinced them that readers like Arjun don't exist.

And the overall desperation within this ecosystem has created opportunities for myself and for others on Substack. Everyone else is losing readers, but we are gaining readers. Why? Well...I would say it's because we're offering a better product—we are able, for one thing, to focus on older books, while most literary periodicals primarily focus on newer ones—but others would say it's basically because Twitter and Facebook and Google used to funnel a lot of traffic to various literary websites, and now because of changes to these platforms, that traffic has dried up and those websites’ underlying business model has been disrupted.

In any case, a lot of the activity that you see in this corner of literary Substack only makes sense once you understand the desperation within the literary fiction industry.

I can't speak for the editors of other newsletters, but here at Woman of Letters I have sometimes toyed with literary populism. As my audience has grown, I've become aware that what I say is taken more seriously within this industry. And I personally have a bone to pick with the kind of literary fiction that big presses put out. I think most of it is very boring and is highly over-praised.

I find it a little offensive that this industry blames the readers for the fact that nobody wants their product when, if you talk to them in private, most of the people involved in writing, producing and evaluating this product are also not that interested in reading contemporary highly-touted new releases.

And I’ve tried to make the case that if this field was more attentive to the pleasure of the reader, then maybe there’d be more interest in its books. This is a drum that I beat upon most recently in the previously-mentioned review of that novel, Woodworking.

I have a tendency, I’m aware, to write my posts with a dual audience in mind. I have many general readers, like Arjun. But I also have many subscribers who are critics, agents, editors, writers, etc. And I know these insiders pay attention to me in part because my subscriber count creates the perception that there’s a large cadre of disaffected readers who agree with what I say about the industry.

This is classic populism. I'm only taken seriously by insiders because I purportedly speak for outsiders like Arjun.

But, in reality, it’s a shell game. Arjun has no interest in all this literary politics. He doesn't really care what big publishers put out. He's just reading this newsletter over his morning coffee, because he's mildly interested in hearing what's going on in the literary world.

Okay so how would you fix everything?

However, I’ve really tried over the last six months to tone down the populism. That’s because I’ve realized that I don’t actually think publishers have a simple or straightforward path out of this mess.

Some of my friends are convinced that if you publish more men, then that would be good and would revitalize interest in literary fiction. I don't know. I have no idea. Nor do I think ‘just publish better books’ is a serious answer.

Personally, I think the problem with publishing is the same as the problem with everything else: oligopoly.

Basically, during the 2010s, global interest rates were low and money was cheap. As a result, the largest companies—not just in the literary world, but in every field—borrowed money and bought their competitors. In the literary world this resulted in five companies, the Big Five, that collectively control about half of the U.S. market for books, and which tend to dominate the bestseller lists and bookstore shelves.

This means that you have less competition. It means that companies are very large, and individual imprints, particularly those that are operated primarily for reasons of prestige (i.e. because the company feels titillated by the idea of publishing Salman Rushdie) are not that responsive to the bottom line.

Moreover, these big guys can stay in business by purchasing their mistakes. Whenever a smaller company manages to exploit a missed opportunity and get some traction, it just gets bought up by the big guys and subjected to a homogenization process that, over the course of five or ten years, destroys whatever made it unique (a process happening currently to Algonquin Books, amongst others).

Without oligopoly, companies that produced a bad product would go out of business. But in the world of oligopoly, large companies can limp along for decades, living a kind of unlife, and dragging down literature as a whole. Basically, all of the imprints that produce all this boring literary fiction are tied, financially, to big companies. And because they're backed by the deep pockets of these big companies, these boring literary imprints are able to crowd their smaller competitors off the shelves. And, at the same time, because they have their corporate daddy's checkbook to draw upon, these boring literary imprints aren't really incentivized to create a worthwhile product that’ll actually sell.

And this whole "we're keeping literature alive" story is just a line that editors need to say in order to flatter their bosses. These bosses are human too, and they like to think they're in the business of preserving culture (so long as it's not too expensive). But eventually those bosses will pull the plug and get out of the literature business.

Now, if this happened, would it suddenly revitalize front-list sales? No, probably not. But it would open up some space on bookshelves, and smaller, hungrier publishers could use this space to take some risks. For instance, it is quite striking that the biggest literary trend of the past five years—romantasy—has been driven primarily by small presses who revamped their entire business model to focus on generating BookTok buzz or on partnering with self-published authors.

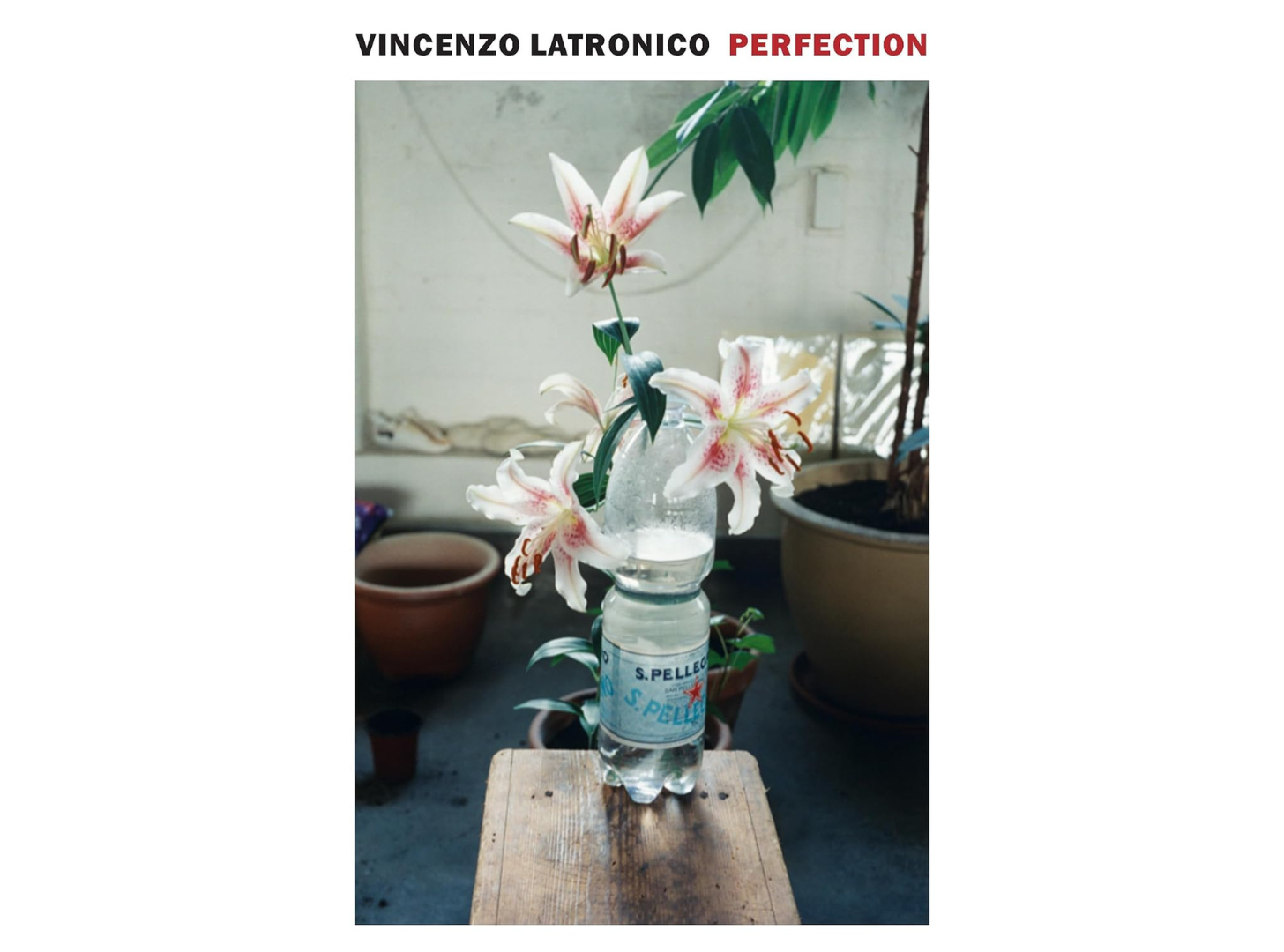

Similarly, many indie imprints over the last twenty years have had commercial success selling translated novels. Elena Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard were both initially published in America by small presses, and just this year there was a novella, Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection, that came out in America from a small press, NYRB, and is out-selling a lot of much-hyped big-press literary novels that had bigger advances and marketing budgets.

How can we serve the reader?

I started this post by writing about Arjun. Fundamentally, this guy is the consumer that literary publishers are desperate to find and cultivate. Right now, we, on Substack, have his attention.

What should we do with that attention?

Personally, I no longer think it’s worthwhile to try and sell Arjun on this literary populism stuff. This idea that somehow the publishing industry will change what it publishes and that this’ll be good for Arjun? It just doesn’t make any sense—he has a lifetime of books that he can read, and he doesn’t care if any new ones are published.2

I do think that because he’s interested in literature, he is somewhat interested in the nature of the literary world. And he’s drawn to these newsletters because they demystify that world and make it accessible.

On a broader level, I also think he’d like to be a part of that literary world. For a long time, highbrow culture didn’t really have a fandom. All the fan activity happened offscreen—at readings in New York or in the pages of literary periodicals. Now that’s different: there are a large number of people on Substack, and on TikTok, who are reading and discussing highbrow literature.3

This is quite different from the highbrow literary world that existed when I did my MFA in 2014. Back then, all our attention was oriented upwards towards gatekeepers. If we were going to succeed, we needed to please admissions committees, editors, agents, critics, awards juries—the reader was really quite secondary.

But now, that old career path—appealing to gatekeepers—has faded. Yes, you can get the fancy agent and the big book deal, but then what? In 2019 or 2020, a publisher could acquire a debut novel for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and there was a decent chance that the book would break out and you’d manage to have a career. Now that kind of breakout debut doesn’t really happen anymore, at least for highbrow books.

In 2025, highbrow writers need to appeal directly to readers. That is something that makes many highbrow writers very uncomfortable, but it’s something they’ll need to learn. External authorities simply cannot confer the kinds of rewards they used to. The pool of readers who will buy a new novel just because The Atlantic says it’s good—that pool is really dwindling. Instead, books can only succeed if they somehow manage to attract the attention of this newly-emerged online highbrow literature fandom.

As a newsletter writer, I think my role isn’t really to influence the publishing industry—they’re too big and slow to change—but to participate in the very exciting online culture that has developed around highbrow books.4

In that culture, I do have something to contribute, because I know a lot about the industry and where books come from. But, going forward, when I write about the industry, I really want to do it in a way that is accessible, informative, and not quite so polemical.

I don’t know where our literary culture is going, all I know is that we’re going there together.

Perfection

This is an Italian novel, only 125 pages long, about a couple, Anna and Tom, who live in Berlin. They’re freelance creative professions: they design websites and marketing campaigns basically. It’s basically about people like me: millennials who moved to the big city in the hopes of being at the center of things. For a while, in our twenties, we were able to convince ourselves that our lives were indeed cool and trendy, but eventually the financial precariousness takes a toll, their friends move away, and Berlin stops seeming so glamorous.

I talked to a friend about this book, and she critiqued it the same way I critiqued Gasda—basically that we all know modern life is vacuous and empty, and this insight isn’t enough to power a whole novel.

Personally, I didn’t think the novel was without sympathy for Anna and Tom. They seem perfectly normal—better than normal. Some of the passages are a little cruel, as in this one that describes their new-found interest in cooking:

All their friends shared this interest. Mysteriously enough, they had discovered homemade fermentation kits, fire-roasted cauliflower, and umami at exactly the same time as Anna and Tom. As they had grown older, the nights out—drug-hazed nights spent sandwiched between tourists—had been gradually replaced by lazy lunches on summer afternoons or candlelit dinners behind frost-covered windowpanes.

But other passages are much more neutral, like this one about how their friends often disappear suddenly:

Periodically someone would disappear. It was more common in winter. Sometimes their landlord would break the lease agreement. Sometimes they would get a job back home. And sometimes there would be no apparent reason at all. At first the friend would stop showing up at openings or replying to messages. Their German number would go straight to voicemail. Soon enough Anna and Tom would hear—either via Facebook or word of mouth—that their friend was back in Marseilles, or Athens, or Copenhagen. Sometimes there would be a proper leaving party with a rented sound system and a plant auction. But more often, what was supposed to be a quick trip home would drag on for months, until the friends who had agreed to keep their bicycle for them would receive an email putting them in touch with some guy driving a van from Berlin to wherever the bicycle owner had returned. We’ll definitely be back, these emails would say, as soon as we find an apartment or a job, once the PhD or the winter is over, once the baby is weaned. And the ones who had stayed would reply, See you soon, can’t wait, so jealous of the warm weather down there, when really they knew their friends weren’t coming back.

Personally, I think the emotional heart of the novel is that these two characters always have each other. You kept expecting their bond to fray or break—for them to have an affair or an argument—but, well, you’ll see what happens.

It’s probably the literary novel that’s gotten the most buzz this year, so it’s worth checking out for that reason alone.

Other Takes

I’ve issued a standing offer that if I cover a book, and you’ve written a Substack post about that book, then I’m happy to link to it. Two readers sent me links to their reviews:

Robbie Herbst had mixed feelings about Matthew Gasda’s novel The Sleepers.

“Time escaped in strange ways, excusing itself like a guest at a party, never really saying goodbye, shutting the door before he could say goodnight,” Gasda writes. “He felt ashamed, and horny,” Gasda also writes. Somewhere between these poles lies The Sleepers: elegant and vulgar, confounding and provocative.

Ashley Honeycutt had a favorable opinion of Jamie Hood’s memoir, The Trauma Plot:

If rape is a societal phenomenon, the thing Hood calls (after Rebecca Solnit) “the longest war,” it’s one where we can talk about how our failure to protect children and young people has consequences for their adult lives in the same way as poor nutrition or a lack of early literacy education. And letting it happen on a large scale, which we do, is not just a personal tragedy, but a squandering of human capital. Hood’s memoir puts a human face on that abstract idea, telling a story about what that looks like in the life of an actual person—a person who closely and tenderly observes the people around her, a smart person who loves learning and thinking.

I think in the last two months I’ve written about Ted Chiang, Woodworking, The Trauma Plot, Hawthorne, Emerson, Thoreau, The Mahabharata, The Sleepers, and, now, Perfection.5 So if you end up writing about any of these books or authors, please let me know!

P.S. I have a deadline for my nonfiction book, What’s So Great About The Great Books, so there won’t be a post this Thursday. That means my next post will be on Tuesday, June 17th.

I’m aware that what I’m writing sounds a lot like Ted Gioia stuff. I like his newsletter! I find it interesting. I think he just puts way too much weight on some abstract theory of ‘cultural stagnation’ and not enough weight on the fact that our population is aging. To me, the aging population is enough, by itself, to account for the trend of older art outselling newer art—a trend that, interestingly enough, even holds true for a relatively new art form, the video game.

In fact when I asked him to read this post Arjun sent me a link to a blog post, by someone named Gwern, that argues, somewhat-facetiously, “old stuff is as good as the new, and it’s cheaper; so making new stuff is wasteful.”

Eleanor Stern wrote a great article in TMR recently about how TikTok helped drive the popularity of I Who Have Never Known Men, a Belgian novel that was recently reissued by a small press, Transit Books.

On a sidenote, the most successful literary Substackers are the ones, like Celine Nguyen, who eschew grievance and populism altogether—they just focus on writing about books they love. Honestly, I owe Celine a lot of credit for the ideas in my post: she’s both an example of the fandom that is arising around highbrow literature, and she is a theorizer about the existence of that fandom—in my conversations with her, she often talks about wanting to nurture that fandom. You can see an example of how that works in her latest post, about becoming a fan of Proust.

Perfection has been Substacked so extensively that it felt pointless to collect other takes on the book. I found dozens of posts that referenced it. Nonetheless, if you’re a subscriber of mine and you posted a take that you want me to link to, please let me know!

I avoid all this drama by writing low-brow, trashy, transparently commercial fiction.

It's almost as if genre readers have been intelligent all along and there's no such thing as "literary" fiction except a desperate clinging to some imagined caste. It's almost as if "literary" readers — the actual buyers of books — read both and only blush when someone tries to publicly shame them for reading "garbage." Frankly, I've often found better literature in the garbage than whatever artisanal culinary experience is being served up by the denisons of "literary."

Midsummer Night's Dream and Moby Dick are fantasy and they're read by "literary" and "low brow" readers alike, I meet these readers at spec fic conventions and MFA programs.

Jane Austin and Edith Wharton write romance, read by all sorts of readers.

The Road and A Canticle for Leibowitz are both apocalyptic novels, ready by all sorts.

I could go on and on, but I'm reminded of the interview The Onion did with Terry Pratchett back in 1995 that Patrick Rothfuss unearthed for us:

"O: You’re quite a writer. You’ve a gift for language, you’re a deft hand at plotting, and your books seem to have an enormous amount of attention to detail put into them. You’re so good you could write anything. Why write fantasy?

"Pratchett: I had a decent lunch, and I’m feeling quite amiable. That’s why you’re still alive. I think you’d have to explain to me why you’ve asked that question.

"O: It’s a rather ghettoized genre.

"P: This is true. I cannot speak for the US, where I merely sort of sell okay. But in the UK I think every book— I think I’ve done twenty in the series— since the fourth book, every one has been one the top ten national bestsellers, either as hardcover or paperback, and quite often as both. Twelve or thirteen have been number one. I’ve done six juveniles, all of those have nevertheless crossed over to the adult bestseller list. On one occasion I had the adult best seller, the paperback best-seller in a different title, and a third book on the juvenile bestseller list. Now tell me again that this is a ghettoized genre.

"O: It’s certainly regarded as less than serious fiction.

"P: (Sighs) Without a shadow of a doubt, the first fiction ever recounted was fantasy. Guys sitting around the campfire— Was it you who wrote the review? I thought I recognized it— Guys sitting around the campfire telling each other stories about the gods who made lightning, and stuff like that. They did not tell one another literary stories. They did not complain about difficulties of male menopause while being a junior lecturer on some midwestern college campus. Fantasy is without a shadow of a doubt the ur-literature, the spring from which all other literature has flown. Up to a few hundred years ago no one would have disagreed with this, because most stories were, in some sense, fantasy. Back in the middle ages, people wouldn’t have thought twice about bringing in Death as a character who would have a role to play in the story. Echoes of this can be seen in Pilgrim’s Progress, for example, which hark back to a much earlier type of storytelling. The epic of Gilgamesh is one of the earliest works of literature, and by the standard we would apply now— a big muscular guys with swords and certain godlike connections— That’s fantasy. The national literature of Finland, the Kalevala. Beowulf in England. I cannot pronounce Bahaghvad-Gita but the Indian one, you know what I mean. The national literature, the one that underpins everything else, is by the standards that we apply now, a work of fantasy.

"Now I don’t know what you’d consider the national literature of America, but if the words Moby Dick are inching their way towards this conversation, whatever else it was, it was also a work of fantasy. Fantasy is kind of a plasma in which other things can be carried. I don’t think this is a ghetto. This is, fantasy is, almost a sea in which other genres swim. Now it may be that there has developed in the last couple of hundred years a subset of fantasy which merely uses a different icongraphy, and that is, if you like, the serious literature, the Booker Prize contender. Fantasy can be serious literature. Fantasy has often been serious literature. You have to fairly dense to think that Gulliver’s Travels is only a story about a guy having a real fun time among big people and little people and horses and stuff like that. What the book was about was something else. Fantasy can carry quite a serious burden, and so can humor. So what you’re saying is, strip away the trolls and the dwarves and things and put everyone into modern dress, get them to agonize a bit, mention Virginia Woolf a few times, and there! Hey! I’ve got a serious novel. But you don’t actually have to do that.

"(Pauses) That was a bloody good answer, though I say it myself."

People forget that Steinbeck's first novel was a pirate fantasy and his second novel was a werewolf thriller. They forget that Hemingway was jilted by the spec fic magazines: he wasn't good enough to sell to the pulps.

They forget because they want to be seen as academic. They want to be seen as smart. They want to have honors and awards and the privilege that comes with prestige. They want the power connected to it. The pleasure of trading favors for being inside some sort of gnostic inner circle.

But these are all proximate goods. They are not beauty, truth, and goodness. They're irrelevant to what great books are actually trying to do.

These readers you're talking about (i.e. all readers) are incredibly intelligent and they don't have discriminating tastes in the sense of genre. What they have is discerning taste: a much better sense for bullshit than the average critic for two simple reasons (1) they're not worried about their own careers in literature, generally, (2) they're curious and joyful with the things they like and don't mind telling you what's good and what sucked.

In this way, plenty of genre writers believe it's their job to improve the reader. Plenty of literary writers attempt genre without having any knowledge of the field and truly believe, for instance, that they're the first one to invent a time traveling super soldier or a nonlinear narrative about a plague or what have you. If anything, there's an ignorance in the literary crowd of the foundational works of literature that isn't present in the genre crowd because, for whatever reason, American lit has been tidally locked around 20th century cynicism for the last century.

It's eating its own tail.

Don't believe me? Take a look at all of the Pulitzer Prize winners for fiction. Ask yourself: in recent years, how many of these are remakes or riffs on classic works of literature as opposed to new stories? Certainly that's allowed — there's something downright medieval in a good way about trying to get your version of, for instance, Arthur or Virgil right — but almost all of them are. The Road was Dante's Inferno. March was Allcot. Gilead was the retelling of the Abraham / Sara story. James was Mark Twain. Demon Copperhead was Dickens.

This isn't a bad thing, but its direct parallel is Hollywood remakes.

Ezra Klein is right here too: we have stopped looking forwards. All of us, that is, but the genre writers and the readers who truly do not care. They are HUNGRY for good, new stories. They always will be — this is why great screenplays always set the pace for blockbusters. I know a brilliant producer who lives in the Hamptons. She reads classics. She reads Game of Thrones. She reads Pulitzer Prize winners. She reads romance. She reads memoir. She doesn't care, she reads it all, and she's that kind of oldschool, blunt, smoker New York lady who will tell you exactly what she thinks and why: she has the literary pedigree to know it all and to deconstruct or exalt it equally. She does. She doesn't care. She's no respecter of awards or sales or whatever.

If the folks in this business stopped talking down to people like her (she — a very educated, wealthy, and powerful reader!), erased the completely arbitrary boundary line, and saw that readers don't care for the genre distinction at all, they would actually revive both sides of the publishing industry. Both sides would benefit because there aren't sides from the reader's perspective. There are merely "books."

That's hard, of course, because both political parties thrive on the arbitrary distinction between "coastal elite" and "rural ignorance." Both pride themselves on their side.

But neither paints the truth of things. As Emerson said, "The city is recruited from the country." We are interdependent. We are interpenetrated with one another. We are, in a way, consubstantial and always-already elite while always-already ignorant; always-already urban while always-already rural. The city eats rural food. The rural folk come to the city for baseball games. It's an endless cycle and it cuts right through literature.

Literature merely means "written works" as in "letter" or "letter of the law."

To be "literary" is anything related to the written word.

That includes all genres and includes all readers, most of whom read both.