The trauma plot has lost faith in itself

One of the hot books of 2014 was a novel by Jenny Offill called Dept of Speculation. This was one of those wikipedia realism books that interspersed little factoids (in Offill’s book the facts were usually about animals or science) with short, descriptive passages about the life of the unnamed writer-protagonist—a mother who felt somewhat stifled and frustrated.

For a while, these books that mixed confessional writing and critical analysis were all the rage. Another similar entry in this canon was Kate Zambreno's Heroines, a 2012 memoir / essay about a woman who was dragged by her husband's job to a little town in Ohio. This writer-protagonist dealt with her frustration by trying to reclaim the stories of the wives of modernist writers—trying to understand and relive the frustration they must've felt, functioning as side-kicks to their more-famous husbands.

Both of these books were essentially kunstlerromane. They were about the development of the artist. In this kind of book, all the pain feeds into the art. Everything you suffered is redeemed by the act of artistic creation.

Another kind of redemption was offered by the outpouring of narrative that followed the #MeToo movement. Women went online to share their stories of harassment and rape, with the promise that this pain would be redeemed by the creation of a world without rape. The patriarchy would be defeated, and the future would be better than the past.

These kinds of trauma narratives attempted to give meaning to trauma by implying that something good might arise from it.

Fast forward a few years, and suddenly, we're not so sure if trauma leads to anything good. In 2025, many women still have to subordinate their own dreams to those of their husbands and kids. And MeToo doesn't seem to have led to a world without rape.

Does this mean that Heroines and Dept. of Speculation are bad books? No. But the force that animated those books—the sense that women’s pain could be made to explain itself—seems to have dissipated.

In 2021, the critic Parul Sehgal wrote an essay for The New Yorker that was about the trauma plot. She decried a perceived trend of writers who seemed to have little to offer besides their trauma:

The enshrinement of testimony in all its guises—in memoirs, confessional poetry, survivor narratives, talk shows—elevated trauma from a sign of moral defect to a source of moral authority, even a kind of expertise.

At the time, I felt like this essay was a bit much. Plenty of the books mentioned in this essay (the Patrick Melrose novels, A Little Life, the work of Knausgaard) are pretty good! I also think Heroines and Dept of Speculation are quite good. Many things can be spun into art. Many writers have a formative experience that they revisit over and over. It's their subject matter, they can write about nothing else. Think of Dickens and all his penurious fathers and orphans forced to work too early. Think of Tim O'Brien's eighteen month tour in Vietnam. Or Sherwood Anderson's bursting free from his bourgeois life in Ohio. Some writers are so affected by a brief time in their life—by a small set of experiences—that figuring out how to explain these experiences becomes the work of a lifetime.

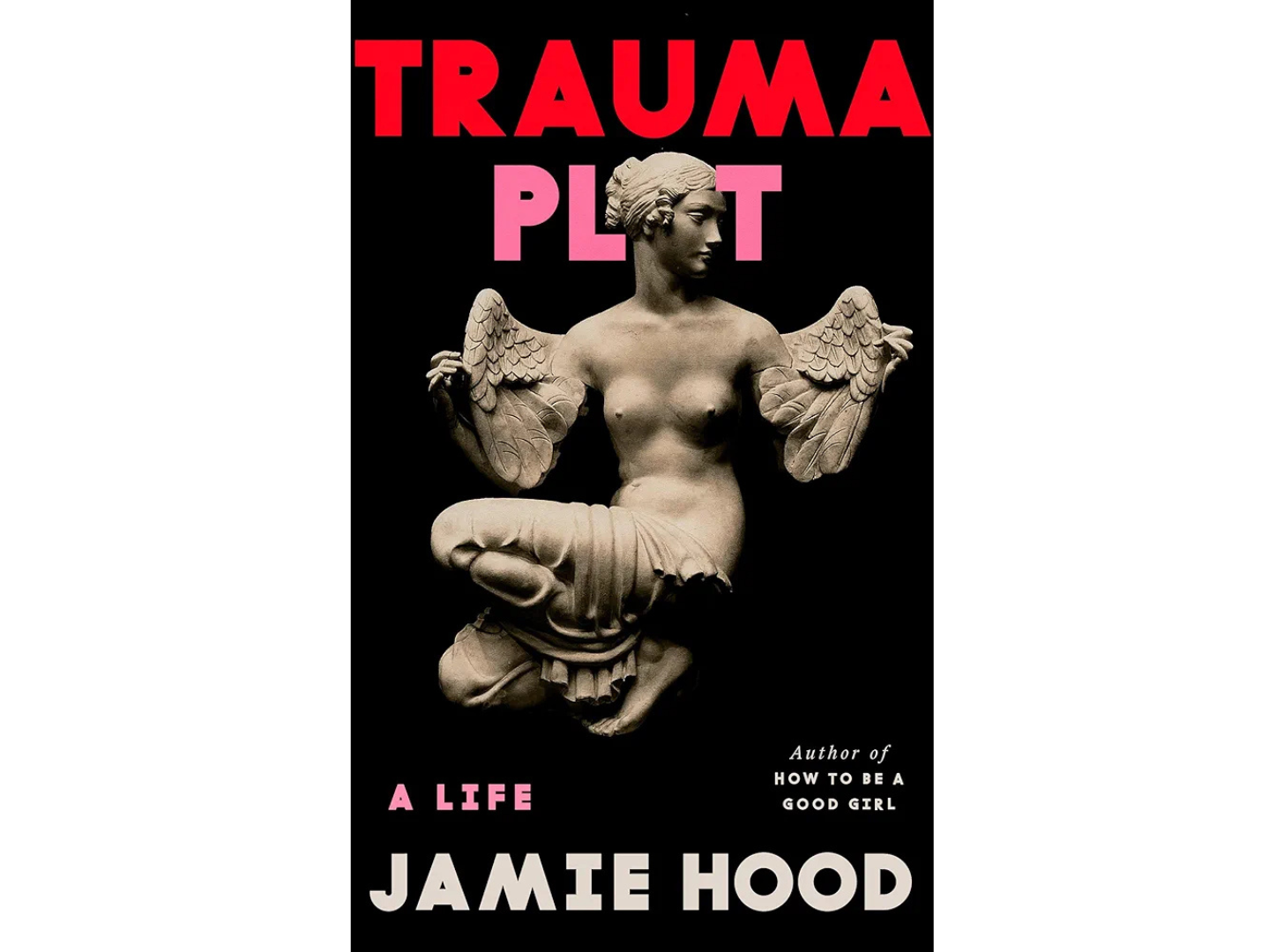

Recently I read a memoir entitled The Trauma Plot. The author, Jamie Hood, was raped three times, in separate incidents over the course of about three years, and the book is an attempt to write a Zambreno-style work of cultural criticism / memoir that attempts to process these incidents.

I found the book interesting and readable. I liked the details, liked the voice. When the story begins, Hood is enrolled in a PhD program, trying to write a dissertation on confessional writing. At the same time, she is partying quite hard, taking drugs, hooking up. Her life seems extremely precarious. She is from a working class background and has no safety net. Meanwhile, it's become clear that she's unlikely to become a professor, so what's next? What will happen to her?

Against this backdrop, she gets raped first by an acquaintance at a party. Then, later that year, she is brutally assaulted, all night, by a man who must've drugged her at a bar somewhere. These two incidents send her into a spiral that leads her to drop out of her PhD program and move from Boston to New York City. She becomes a sex worker, and she gets assaulted again, in an incident even worse than the previous two.

Mixed in with the narrative, she details her attempts to make sense of these experiences. The book takes a variety of approaches: it's kaleidoscopic both in its playing with point of view and narrative distance. Sometimes we're embodied within the Hood of the narrative, going through her life with her. Other times, we're distanced. Hood tries to argue with Sehgal, to insist on the importance of confessional writing.

At the same time, she does not believe in the possibility of justice (and in any case is against the carceral system). Nor does she seem to believe in the chance of a better world, where women don't get raped. Moreover, she wonders at times if she's imposing more meaning on these rapes than they really merit:

At moments I wonder if my writing this book—digging through your history in this way—is unethical or dishonest, if I’m exposing you. I wonder if the rapes were less disruptive than I’d imagined. Do I thrust on your experience a traumatic significance that wasn’t there? Is it my job, or perhaps my crime, to assemble plot, to force on your behavior an ineluctable causality? It’s entirely possible I gather your confessions from the wreckage of your accounting to pathologize you, to frame your actions like the motion of a rubber band snapping back.

She also feels the sting of Sehgal's critique. Is this book really worth writing? The book itself is mostly the record of an attempt to write a book:

Like, why would anyone care, besides me and the people who love me? To tell “my” story demands exceptionalism, it’s premised on the notion that my particular life has, or should have, a range of possible audiences—different people with whom the narrative can connect. Art, in my view, should transport those who encounter it, should be larger than itself. The act of turning my rapes into an art object, making of them a kind of thing, presupposes that this thing does more than record or relay a sequence of events. The thingness of my survival mandates import.

With this book, it's easier to excerpt the more manifesto-like elements—the parts that seem to be in Hood's omniscient voice—because the story elements are told in a variety of modes and variety of voices. Sometimes this can be confusing, and it can be difficult to situate oneself within the narrative, but it's mostly fine.

My critique of the book is the most obvious one: the trauma seems meaningless, inexplicable. As a result, the book is very depressing.

This critique is a bit unfair, I suppose, because this is a book that's about the perceived enervation of the trauma plot. Once upon a time, ten years ago, we believed that telling women's stories mattered. Then, somehow, we stopped believing that, because fashions changed. This book purports to be a defense of the notion of confessional writing—it tries to square the circle, restoring us to a world where we think testimony matters.

But I think it's a mistake to say that we ever believed in the abstract notion of 'testimony'. With testimony, the aim was always for some some broader effect, some sense that this story adds up to more than a recitation of trauma, either because it formed a human being who is good and strong, or because it'll lead to a world where other people don't have to suffer like this.

I don't think that belief in a better world—a belief that suffering has meaning—is something that an author can (or should) fake. But absent that meaning, a trauma plot becomes unbearably sad. Hood is a great writer and a brilliant woman—her life was thrown into disarray by these terrible events, and she will never regain what sexual assault has cost her. It's just so senseless. There's no meaning to it.

Personally, I found the book interesting and enlivening, but quite depressing, I would love for someone else to read this book and tell me that I'm wrong, and that there's more here than I perceive. That somehow there is meaning in this attempt to struggle with whether or not this story is worth telling at all.

Perhaps it's silly and shallow of me to expect more from this book. This story was Hood's obsession. For her own sake, she needed to tell it.

The whole final section of the book consists of her attempts, with the help of her therapist, to attempt to write the book we are reading. She considers and rejects many of the arguments in favor of the trauma plot, just as she rejects many of the arguments against it. Her powerful intellect is easily able to argue that of course women’s stories are important. At the same time, it's able to interrogate that desire and argue against the idea that there's any true cure, any true ability to get over the trauma. And if that's the case: what's the point of writing about it.

She's left only with the force of her own compulsion. Right or wrong, this story is one that she needs to tell. As a writer, it is her subject matter. And whether it's good or bad, it's all she can write:

Rape muted me for many years, but when I began to write into the chaos, I couldn’t stop. I needed to puzzle through it in every way, in tweets and poems and essays and criticism. Public and private. Because every form was stained. All art was.

And I feel mindful of the critique that this story is too intensely personal and doesn't have much to offer the reader, because essentially the entire book is written defensively, precisely to forestall that critique.

Every possible criticism of this book is brought to the surface, but the effect is only to cement those criticisms in the reader’s mind. For instance, on the idea that the book might be too raw, might be lacking in art:

But why should I make my rape book artful? Why be cowed by this obligation. Shouldn’t trauma be a mess? What if I let it be a performance, a public flaying—is it not better to provoke than appease? I won’t prettify it. And I can’t trust any impulse to aestheticize my violation. It’s an unsettling imperative. It pivots on the belief I might make my rapes beautiful, and then who would I be?

Or, regarding the idea that this trauma might have made her a stronger person:

I tell her, of that cliché about surviving trauma. That it makes you stronger, or makes you the person you are, teaching you profound lessons about the sort of life you should want to lead. Instinctively I retch—it’s grotesque and patronizing, like you’re some fairy tale dolt who can’t see the moral of a fable until you’ve been savaged and left for dead in some sad forest. I could easily have been a strong, resilient, astonishing person without having endured decades of violence.

Or, regarding the idea that perhaps there is some justice that's possible for her:

I never reported, and I’ll name no man in these pages. My dream isn’t any longer of vengeance, and if I know anything, I know what the carceral system metes out isn’t justice. Policing is the opposite of futurity.

The end result is somewhat frustrating. The book defends the telling of these stories, but it's unable to say why telling these stories is important. The book can only say that because trauma victims find it to be necessary to say these things, then these things must be said.

I don't know. I've read memoirs of many kinds of traumas, but almost always they're stories about some kind of escape or redemption. With The Trauma Plot, the escape felt so empty, so provisional, that it really seemed like it evacuated the trauma plot and ended up proving the point it set out to argue against—this author was so haunted by these events that she was trapped forever, circling within them, until she could publish a book about them. And the implications seems to be that if bad things happen to you, then…you're just stuck. You're marked forever by what's happened to you, and there's no escape. Which might be true, but it's quite depressing.

Perhaps this is just my perspective, but I've come to realize that unadorned truth isn't necessarily a worthwhile artistic effect. Ultimately, it's quite easy to make the world seem bleak and hopeless. What's difficult is to make the world explain itself somehow. In the end, this book is a rejection of the various kinds of stories that can be told about trauma. But if trauma truly cannot be made to yield any meaning, then this book can only function as a comprehensive rejection of the trauma plot itself.

It should be noted that Hood is trans. This fact goes unremarked-upon within the marketing materials for the book, and it is only mentioned glancingly in the text—an inattentive reader could easily miss it.

I'm not totally sure what to make of the fact that transness has been elided from this text. I feel like the book will mostly be of interest to other trans people—that's exactly the reason I'm reading it after all—and that by trying to make the story more relatable to cis audiences (who will likely never encounter it), the book's appeal to its primary audience has been reduced.

But I've also written before on the ways that writing trans fiction can feel like a trap, and I can more than sympathize with the desire to escape that trap. And some trans readers, I know, will enjoy that the trans identity isn't so front and center. We like to read about ourselves, but at the same time it can be nice to read ourselves written as women, no different from anyone else. So, ultimately this aspect neither works for or against the book—its just a fact I thought it was worthwhile to mention.

I've focused mostly on the exegetical scaffolding that Hood wraps around her story, because her arguments about the trauma plot itself are the thing that's easiest to discuss in a book review. Without those arguments, I'm not sure I would've kept reading, because the core story is so dark, so awful. To be raped once is one thing, but to be raped again and again is another level of horror. And then that story is combined with a level of economic precariousness that I'm used to, from knowing so many trans women, but which is still hard to confront head-on.

On that level, the book certainly worked. Hood’s attempts to tell this difficult story were compelling enough that I was willing to read through to the end, just to see if the plane would land successfully. In the end, I'm not sure it did, though I'd love if some other BookStacker read the book and told me I was completely wrong and that it does somehow manage to fulfill its promises to the reader.

I’ve created a graphic memoir about my experience of being diagnosed with breast cancer aged 37 (I’m 40 now and recovered, but this was traumatic for sure). My book will be published later this year.

I used to disagree with the idea that you have to suffer to create art. Then I suffered, and created the best art I ever have.

I still disagree with the idea that suffering is essential to art. How do I square that with my own work? I think it’s because I made decisions and creative choices. It’s a story that’s truthful, but it’s a story. I processed my trauma through therapy. Not in the pages of my book. I needed a little distance from my story to tell it well - but not too much, because I also wanted that rawness and urgency.

It’s a fine balance between “authenticity” and “creativity”. Memoirs are stories, just like any other story. You still have to think about the reader. If you want people to buy it and read it.

I think I shy away from trauma plots where it feels like the author is just recounting miserable experience after miserable experience with no light at the end of the tunnel, or if it feels like the trauma is there for shock value. But literary trauma that's carefully treated and deconstructed can be much more meaningful to me than other works. There's a balance to be struck between naively romanticizing trauma and writing glorified grimdark. You're right that the raw trauma life throws at you isn't often artistically valuable. But the best authors will take that raw material and glue or reforge it into something that's particularly meaningful to them in the process of recounting it on the page. And the reforged, reinterpreted substance is what I'm interested in.