All of my literary success is due to reading this one classic text

Whenever a post goes viral and I gain a new burst of readers, I have to break in and remind people that actually…this is a Great Books blog. It was originally started in 2023 to promote my book (hopefully coming out from Princeton University Press in 2026), about reading the Great Books.1

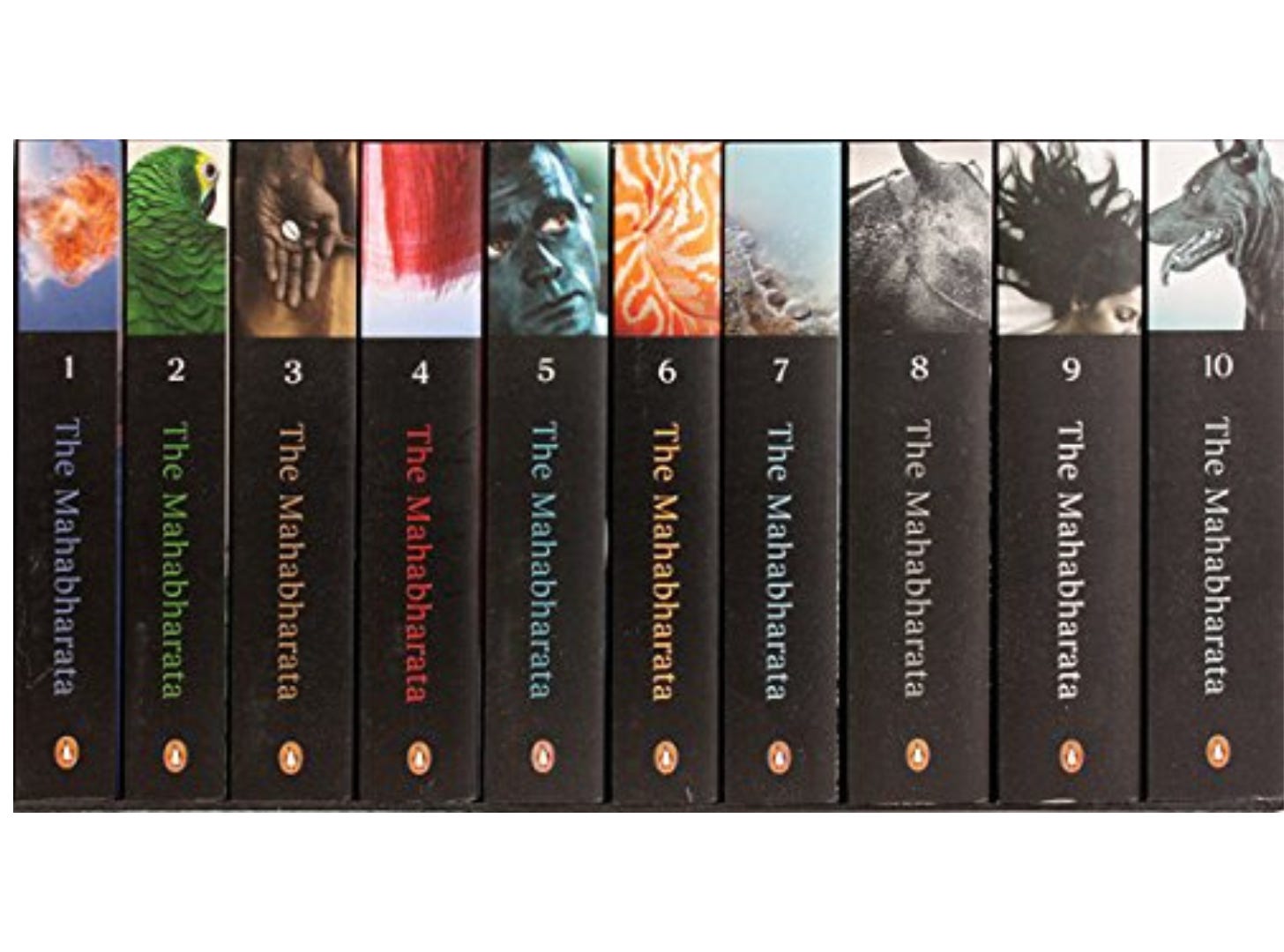

Yes, I publish my own fiction here, and I often write about contemporary literature, but I still post primarily about the classics. And the major classic that I’ve posted about for the last year has been the Bibek Debroy translation of the complete Mahabharata—a two thousand year old Sanskrit-language epic.

When I posted about the Mahabharata for the first time, I had fewer than a thousand subscribers. Surely some of those have unsubscribed in the intervening time, so that means only maybe 800 of you have been around for the full journey.

Yes, I am saying ‘full journey’. I finished reading the Mahabharata this weekend!

What’s funny is that when I started reading the Mahabharata, I wrote some extremely dismissive posts about the Hindu faith (I am Indian and from a Hindu background). But over the course of reading this book, I have started believing in and practicing Hinduism. Like…I go to temple now. That’s how far it’s gone.

Reading the Mahabharata has been the best decision I ever made. There’s a reason the text has lasted. It is incredible, life-changing. I would compare it to the Bible, another book that also astonished me once I finally read it—long-time readers will know I regard the Bible as essential reading for literary people.

I would say reading the unabridged Mahabharata is somewhat rarer than reading the Bible, because in Christianity there are certain faith traditions that are built around reading the Bible in translation, whereas in Hinduism this is less common—my impression is that it's much more common for Hindus to read an unabridged version of the other Hindu epic, the Ramayana, either in the original Sanskrit or in a very popular vernacular translation that is a classic in its own right.

But I’m glad I read the Mahabharata. This text has radically changed my life. I’ve written a little in various places about the understandings I’ve gotten from it, but I really think, especially if you’re from a Hindu background, the best thing is just to read it yourself.

The experience of reading the Mahabharata

The difficulty with reading this text is that…well, okay, the first four books are very fascinating, almost effortlessly engaging, but after those books the reading experience becomes much more difficult. The next three books are an almost unfathomable slog, through mindlessly repetitive battle stuff. However boring you think it might be, it’s actually ten times more boring than that. It is amongst the most bored I’ve ever been in my life. I definitely did some skimming.

Then, for the remaining volumes, the Mahabharata gets into all the details of dharma, kingship, vedic cosmology. It really stops being a story and starts being a philosophical text.

My theory is that all the battle stuff is intended to force you to forget about the story—it’s there to kill your expectation that reading the Mahabharata will be at all interesting or engaging. It kind of cleanses your mind, so that when you get to the philosophical stuff, you’re ready to listen. It’s hard to describe, but these ten volumes really do work as a cohesive reading experience. There’s a reason it has lasted.

I have no idea what non-Hindus would make of the Mahabharata. It is so alien, this world. There is nothing recognizable in it for the Westerner. Robert Boyd Skipper has been making a go of reading it (he is up to volume six), and I have to say I am very impressed. I had my doubts that any Westerner could actually read it.

For a person from a Hindu background, you’ve often heard the story of the Mahabharata so many times that it gives you something to hold onto. Like, I have heard of many of these characters and incidents before. I have also read several abridged translations of the Mahabharata. As a result, I am not coming to it fresh—I am really coming to it as a way of enhancing a story that I already know.

I know that I have a fairly large cohort of Indian readers, and I highly recommend that you start reading this. Just do what I did and wake up at 5:30 every morning and read for thirty minutes. Eventually it’ll be over. I did kind of slack off with this last volume, and it took much longer for me to read than any previous volume, but I got through it eventually.

What exactly have you been reading?

The edition of the Mahabharata that I’ve been reading has about 2000 chapters. And each chapter has a speaker and a listener. Oftentimes a chapter begins with a question from the listener—sometimes in the question the listener asks the speaker to elaborate upon the previous chapter.

This call-and-response structure tends to be elided from most abridgments of the Mahabharata. This structure is also what makes the Mahabharata infinitely extensible and creates a sort of anthology structure. At any point, one speaker or the other can interject, asking a question, which in turn creates a digression, during which the speaker can tell a story or teach a lesson. For instance, at one point Bhima encounters Hanuman, and Hanuman tells him an abridged version of the other Sanskrit epic, the Ramayana.

As a result, the Mahabharata often resembles a series of debates or discussions.

What is the story of the Mahabharata?

The core Mahabharata story is about two sets of cousins, the Pandavas and the Kauravas, who have a dispute over which will inherit the kingdom of Hastinapura. The leader of the Kauravas, Duryodhana, is brave and strong, but he’s not good. He undertakes a series of dirty tricks to dispossess the Pandavas of their kingdom. Ultimately, he wins it from Yudhisthira, the leader of the Pandavas in a dice game. And during this game, he dishonors Draupadi, the wife of the Pandavas, by forcing her to disrobe.

As a result of this dishonor, the Pandavas find themselves more or less forced into a war with the Kauravas, the Kurukshetra War. The leader of the Pandavas, Yudhisthira, really doesn’t want to fight, doesn’t want to kill his cousins. He is devoted to dharma—right action. He doesn’t think it is right to fight and kill to win a kingship. There are many extensive discussions where his wife and mother and brothers attempt to convince him that, as a prince, his dharma is to fight and become king. He allows himself to be convinced, and the resulting war is terrible in its carnage: millions of people die, including many of the older generation of warriors who had served as mentors to both the Kauravas and Pandavas.

How does the unabridged version different from most abridged versions?

There is a core Mahabharata story that every Hindu is familiar with. It includes the above, and it also includes a number of incidents from the Princes’ childhood, from their time in hiding, from the war, and from the aftermath of the war.

This core Mahabharata story is only about a fourth of the unabridged Mahabharata. The rest of this ten-volume collection is taken up with the following things:

An older substrate of stories and tales, involving sages like Vasistha, Vishvamitra, Parashurama, Bharadvaja, Asita-Devala, Jamadagni, etc.

After the war starts, thousands of pages of lovingly-detailed (though somewhat repetitive) fight scenes.

A large section, set after the war, where Bhishma, the uncle of the Pandavas and Kauravas, gives advice to Yudhisthira on the nature of dharma.

In addition, the unabridged version tends to be told in long, lush paragraphs, and there’s often a lot of repetition—for instance, in one section Krishna is trying to tell Yudhisthira to shape up and not be so sad about all the deaths that resulted from the war, and to make this point Krishna decides to talk about twenty different mythic kings whose sons died, and how these kings didn’t succumb to despair.

Why read the unabridged version instead of an abridged version?

It’s difficult to imagine anyone coming first to the Mahabharata by reading the unabridged version. In practice, most Hindus have already heard the story so many times that it’s impossible for us to come to the story fresh. For us, reading the unabridged translation is a chance to come as close to the source material as we’re likely to come.

If you’ve never heard the Mahabharata story before, then starting with an abridged version is probably best. I actually purchased the six most popular abridged versions earlier this year. and I’m hoping to compare / contrast them for a future post about what kind of reading experience is offered by these texts.

Personally, I had a religious experience while reading the unabridged version. This never happened, for me, with any of the abridged texts. So…I would say that's the major difference. There is definitely some level of spiritual insight in this unabridged version that you cannot get from the abridged texts.

Thematically, the Mahabharata is largely concerned with dharma—determining the right action in a given situation. And this unabridged version has lots of open discussion of dharma. It has lots of little tales that deal with dharma. It has hundreds of pages—ones usually cut from most abridgments—that are a direct discussion of the nature of dharma.

I think if the point is to get some deeper understanding of dharma, this unabridged version is one of the best possible ways.

And then of course…there’s the religious reason

One continual refrain in the Mahabharata is that just through reading this book, you can gain religious merit. It hasn’t escaped me that during the year I’ve spent reading and writing about this book, my subscriber count has gone from under a thousand to over seven thousand, and my profile as a writer has gone up immensely.

Now, my Mahabharata posts tend to be amongst my less-popular posts, but…so what? That’s just another way of saying they’re the most necessary part of the blog: they’re the thing that my readers would’ve been least likely to come across on their own.

Maybe…my reading and writing about the Mahabharata is precisely the reason I’ve had so much good fortune this year. It’s certainly not impossible. I mean…it’s literally what the book says. These are the final lines of the tenth volume:

If a person seats himself at the feet of brahmanas and hears this at a funeral ceremony, his ancestors always obtain infinite amounts of food and drink. During the day, one may commit sins with one’s senses and with one’s mind. However, subsequently, if one listens to the Mahabharata in the evening, one is freed from one’s sins. O bull among the Bharata lineage! Everything about dharma, artha, kama and moksha can be found here. What is here can be found elsewhere. But what is not here cannot be found elsewhere. Those who desire prosperity should hear the history known as Jaya, irrespective of whether they are kings, the sons of kings, or pregnant women. A person who desires heaven obtains heaven. A person who desires victory obtains victory. An expectant woman obtains a son. A maiden becomes extremely fortunate. For the sake of ensuring dharma, the lord Krishna Dvaipayana, who will not return, composed a summary known as Bharata and it took him three years. Narada recited it to the gods, Asita-Devala to the ancestors, Shuka to rakshasas and yakshas and Vaishampayana to mortals. This history is sacred. It is deep in meaning and is as revered as the Vedas. With brahmanas as the foremost, it should be heard by the three varnas. O Shounaka! A man who does this is freed from sin and obtains fame. There is no doubt that he advances towards supreme success. If one faithfully studies the sacred Mahabharata, or even if one studies one quarter of it, one is purified and all one’s sins are destroyed. In ancient times, the illustrious maharshi, Vyasa, composed this. The illustrious one made his son, Shuka, study it, with these four shlokas. ‘Thousands of mothers and fathers and hundreds of sons and wives arrive in this world and then depart elsewhere. There are thousands of reasons for joy and hundreds of reasons for fear. From one day to another, they afflict those who are stupid, but not those who are learned. I am without pleasure and have raised my arms, but no one is listening to me. If dharma and kama result from artha, why should one not pursue artha? For the sake of kama, fear or avarice, and even for the sake of preserving one’s life, one should not give up dharma. Dharma is eternal. Happiness and unhappiness are transient. The atman is eternal, but other reasons are transient.’ If a person awakes in the morning and reads Bharata, which is like the savitri, he obtains the fruits of reading the Bharata and obtains the supreme brahman. The illustrious ocean and the Himalaya mountain are stores of riches. The famous Bharata is said to be like that. If a person controls himself and reads the account of the Mahabharata, there is no doubt that he advances towards supreme success. This is immeasurable and emerged from the lips of Dvaipayana. It is auspicious and sacred. It is pure and removes all sin. If a person controls himself and listens to Bharata being recited, there is no need for him to sprinkle himself with water from Pushkara.

If you want prosperity, you read this book. I read the book, and subsequently my prosperity increased many-fold.

Elsewhere on the Internet

I recorded a podcast two weeks ago with Kevin and Gordon at Synthesized Sunsets, where we discussed one of my favorite subjects: the tale.

Index of Mahabharata Posts

Volumes 1 and 2

Volumes 3 and 4

Volume 5

Volumes 6 and 7

Volume 8

“The most important news you’ll hear about today” - This post, a sort of obituary for Bibek Debroy, attempts to contextualize the size of his achievement

Volume 9

Volume 10

I have an intro to the Great Books idea here. I also have a list of Great Books here; and if you want a more expansive list, you can check out greaterbooks.com.

What abridged version of the Mahabharata would you recommend for someone new to this world? 🙏

Just finished _Orbital_ by Samantha Harvey: gorgeous lyrical amazing read.