Hinduism doesn't exist

I met a white woman at a reading recently who told me she was Hindu. I said, “In what sense?” She said, “In the sense that I’ve had real experiences of seeing Kali, and I worship her.” I said, “Oh okay that’s great…” but in my mind I was thinking that’s not really Hinduism, as I understand it.

Sometimes Hindus take pride in not being a proselytizing religion: believe whatever you want, we say! Your God is as good as our God.

But it’s not entirely true that Hindus don’t proselytize (look at Osho or ISKCON). What’s more accurate is to say that Hinduism doesn’t really exist. There’s no way to convert to Hinduism, because there’d be nothing to convert to.1 Hinduism, to the extent that it exists, is a set of practices that are largely communal, so it’s almost impossible for someone who wasn’t born Hindu to truly practice the religion.2

I think for Christians this is difficult to understand, because Christianity is very heavy on dogma, but low on ritual. This has proven a problem. Because the practice of Christianity is nothing more than the affirming of a set of beliefs, Christians have historically been willing to war on each other over very minor doctrinal differences (like whether Christ’s nature was fully divine or if it was simultaneously human and divine).

Hinduism is somewhat different. Hinduism revolves not around metaphysical dogma but around rituals intended to increase personal purity. Some people and some practices are considered impure by nature. The brahminical caste is the most pure and acts as the arbiters (for many Hindus) of what is pure and impure. Your metaphysical beliefs are much less important than your adherence to the purity practices of your community. That’s why you have the phenomenon of 19th-century Hindu reformers who are extremely heterodox in their views (some are basically monotheist), but in their practices they are orthodox brahmins.3

It’s very difficult to define Hinduism other than through a set of practices that different groups of people follow to different degrees. I’m obviously a Hindu. My parents, though atheists, are savarna (i.e. they are from the higher castes). My extended family tends to practice vegetarianism and engage in a number of ritual observances that are adjudicated by brahmins.

The tricky part comes when you evaluate lower-caste people and indigenous people (adivasis). Many of them do not have contact with brahmins. They often have their own gods, which have different names than we associate with traditional Hindu gods. The degree to which they identify their religion as being the same as my religion often varies wildly. They usually are not vegetarian and as a community do not keep to various taboos (against dogs, corpses, handling excrement, etc).

But oftentimes these lower castes and indigenous people do aspire to adopt brahminical Hindu practices! Historically, there are two processes that bring fringe groups into Hinduism: brahminization and kshatriyization. brahminization comes when a social group starts to adopt various purity taboos associated with the brahmin caste. This happened to a large extent amongst the caste and geographical group I share with Gandhi: the banias of Gujurat. Gujarati banias are kind of mad for purity taboos: they’re very into vegetarianism, not drinking, studying scripture, adopting celibacy, doing ritual observances, etc. But to a lesser extent this happened to vaishyas all across Northern India—sometime in the last two thousand years, we (the merchants and traders, the proto-bourgeois class) turned ourselves into mini-brahmins and got upgraded on the purity totem-pole, reaching a place where we could access scriptural learning and mingle (one some level) with brahmins. That’s brahminization.

The other phenomenon, kshatriyization, is named after the warrior caste, the Kshatriya. This is what happens when fringe groups (often indigenous people or Sudra) adopt Hindu dogma without adopting these purity observances. These groups might pray to the traditional Hindu gods and study the Vedas and Vedantas and other holy texts, but they still eat meat, slaughter animals, and generally don’t engage in observances designed to maintain purity.

To some extent, this is practical. I personally don’t engage in all the purity observances, so I cannot even begin to tell you what they are. There are so many though! There are rituals for everything! From my point of view, they all seem to involve taking a statue of a God and smearing red paste on it, then bathing it in milk, waving some incense around, and chanting in Sanskrit. How’re you gonna do that stuff if you’re a low-caste person who brahmins won’t even talk to? All that ritual observance isn’t something you can learn from a book—it’s not even homogenous across India. It’s very specific to each time, place, and social group. You could develop your own rituals, I suppose, but what’s the point, if nobody else recognizes them as actually being purifying? The ritual is only meaningful if it’s social.

These processes contains considerable social benefits! For one thing, it makes you legible to the ruling class. The higher-caste people in your community or region (clerks, landlords, government officials, etc) might know you’re a tribal or lower-caste person, but your religion has become legible to them. The God you worship is really Rama. Your religious rituals have similar names and a similar ‘feel’ as higher-caste ones. It just lessens the amount of friction that comes when the two cultures interact. Caste always remains as a divide that cannot really be bridged, but some castes are more impure than others, and to the extent it’s possible, brahminization and kshatriyization reduce the practical and social consequences of your lower caste (and allow you to move up, vis a vis other castes that haven’t engaged in this process).

My acquaintance from the reading is engaging in a practice that more or less resembles kshatriyaization. She’s worshipping Kali—a relatively minor, but recognizably Hindu, God—without engaging in traditional ritual observance. My impression is that some form of kshatriyaization is quite common for Indian hijras. Even hijras who were originally Muslim will often worship Indian gods, and hijra communities have developed their own rituals and forms of observance that serve to fit them somewhat into a Hindu framework, even though nothing can really expunge the impurity of being a hijra.

In India there’s also a community of women, largely from higher-caste backgrounds, who’ve tried to distinguish being trans from being a hijra. They’re very adamant about saying I’m not that thing, I’m this other thing. Instead of fleeing their communities and giving up their caste, like a hijra, they attempt to retain their former practices and social station. I genuinely have no idea the degree to which this is possible. Even the most-westernized Indians are not as westernized as you’d think, because the most-westernized Indians are often brahmins and, thus, have a lot invested in the caste system! Thus the people most likely to be in a milieu where everyone would be familiar with trans women and the concept of trans rights are also the people whose milieu would likely include the most rigid purity taboos.

My understanding is that westernized high-caste Indians have their own set of purity practices that give lip service to Western ideals of inclusion without ever affirmatively engaging in impure practices. They will work with scheduled-caste (i.e. Untouchable) people at the office, but won’t invite them into their homes. They will mingle with meat eaters, or dabble in meat-eating, but will maintain vegetarian households, with vegetarian cooks. Especially since many households are both multi-generational (i.e. you have older and traditional people coming over) and are multi-class (you have servants living in the household who would observe if you engaged in impure practices), there’s a strong temptation to make the household the site of orthodox practice.

In India there are also castes and tribal groups that’ve not engaged in the brahminization or kshatriyaization processes. These groups have ritual observances very different from Vedic Hinduism. Their Gods have different names! Their stories are different! I once read a book by a dalit with the title Why I Am Not A Hindu. He said growing up we never considered ourselves Hindu. We worshipped our own gods. We didn’t know about or read the Hindu epics. In school they tried to tell us we were Hindu, but we knew it wasn't true. Yet according to India’s legal system, dalits are considered Hindu.

Similarly, there are the Jains—an ancient religion that dials up purity-culture to the nth degree. Jainism isn’t a Vedic religion—they do not accept the oldest Hindu holy books, the Vedas, as a particularly privileged source of truth (orthodox Hindu regards them as authorless, given to us directly by the divine). But Jainism looks and feels a lot like brahminical Hinduism, particularly in its practices: vegetarianism, non-violence, a focus on pursuing your dharma (the right action for a person in your position). And Buddhism, though it rejects the caste system and a lot of the ascetic practices of Vedic Hinduism, historically looked a lot like Hinduism—but in modern-day India this is complicated because most Indian Buddhists are neo-Buddhists (lower-caste people who converted to Buddhism in the modern era to try and escape the caste system).4 In practice, it’s very difficult to find a line that would clearly separate Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism without also cleaving from Hinduism many groups that do regard themselves as Hindu (just like it’s very difficult, in practice, to figure a definition of Christianity that would allow Mormons to be Christian while excluding, say, the Muslims or the Cao Dai).

Further Reading

To some extent, this post is prologue to a bunch of stuff I want to discuss over the next few months. I’ve been reading the unabridged Mahabharata in the new Bibek Debroy translation, and it’s incredible—a font of stories and philosophy like nothing I’ve ever seen before. Just unbelievably fertile. At the same time, I’m very aware that almost none of my readers are going to read it. All they’ll ever know about it is what I say. So I’ve been thinking about what exactly I want to write about these books for my audience. Most of my audience grew up in a Christian context, even if they don’t actively affirm those faiths, and I think there’s a strong tendency for Christians to categorize other faiths by their dogma, rather than by their practice. In general, the habits of mind that you develop when you’re dealing with exclusive religions are pretty useless when dealing with polytheistic religions, and I thought it’d be good to unpick some of those assumptions before I started talking about the Hindu holy books.

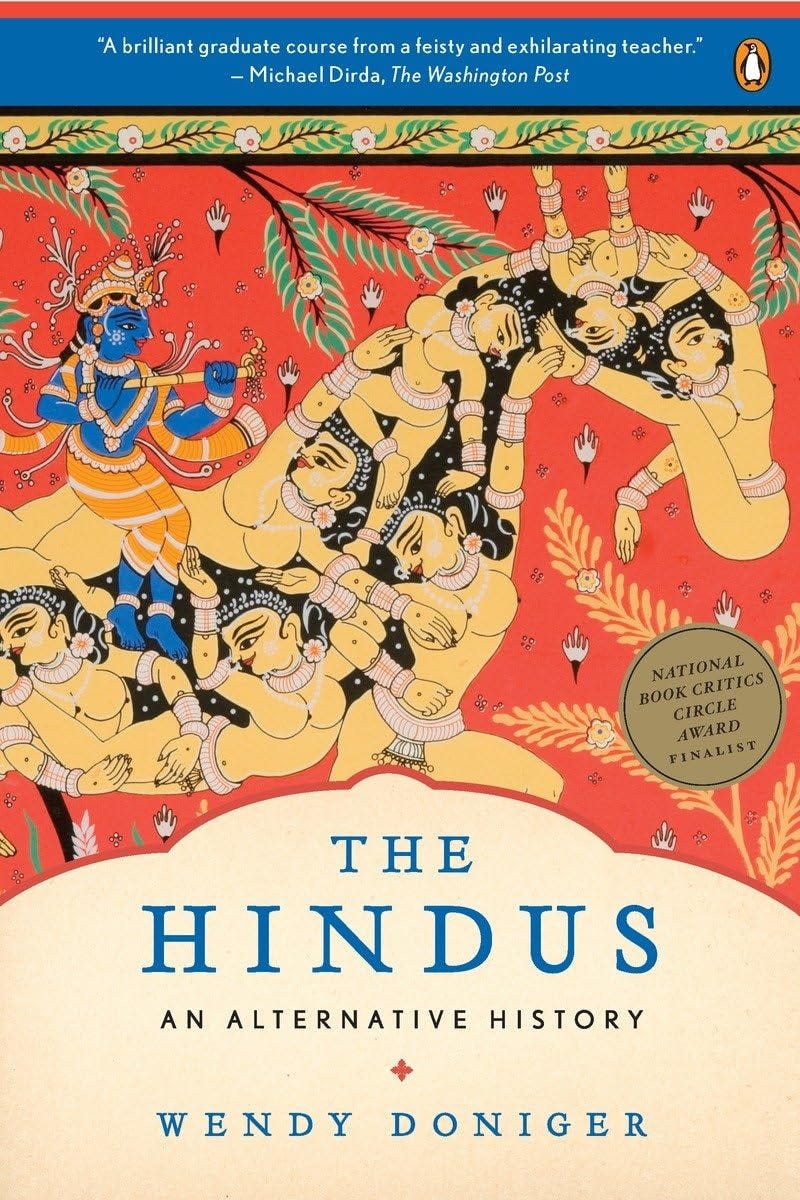

My own religious education (at least in Hinduism) has been haphazard, and I’ve been working assiduously to clear up the gaps. The best book I’ve read on the subject so far is Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternate History. This is exactly the book you want if you’re reading Hindu texts as literature. The problem with most modern-day explications of Hinduism is that the religion has changed quite a bit over the last three thousand years! The Hinduism of the Mahabharata is already quite different from that of the Vedas. But even the Hinduism of the Mahabharata is very, very different from modern Hinduism. Doniger tracks these changes over time, and does it from a literary standpoint, with lots of quotes from the literature of each time period, and with a sly, cheerful voice to boot! Doniger is probably the preeminent American academic Sanskritologist, although I know to most Indians that’s like saying she’s the most prominent American expert on reducing gun violence.

When reading about India, especially in the English language, the biggest problem is that the sources are dominated by Hindu nationalists, aligned to right-wing movements in India, who have a vested interest in white-washing every aspect of India’s past and history. To them, India has the oldest civilization in the world, it invented all the greatest stuff, it’s the most egalitarian, the wisest, etc. There’s no critical thinking at all. (It’s exactly the same as when you Google Christian topics!) There’s a not-insignificant chance they’ll get a hold of this paragraph and drag me over the coals, which would be such a pain, but I suppose I’ll live.

Hinduism is so difficult to convert to that in the 19th-century, when some Indians regretted their conversion to Christianity and wanted to become Hindu again, nobody had any idea how to make that happen. Eventually some obliging Brahmins created some ritual observances that would re-purify the straying Hindus, but I bet the effort was only somewhat-successful. Some losses of purity can only ever be partially effaced—some people in your community will always persist in thinking you are still tainted by having engaged in impure practices.

This sounds like I’m calling out cultural appropriation, but actually I’m doing the opposite. I don’t think it’s even possible to appropriate Hinduism.

Gandhi was in some ways the opposite: he believed in caste (the idea that some are born less pure and with less merit), but he didn’t believe in the rituals of purity surrounding caste—this, to many Hindus, made him impure. But when he’s evaluated by outsiders, Gandhi seems mealy-mouthed, because while he condemned the practice, he didn’t condemn the dogma of caste.

It’s actually quite shocking how marginal Buddhism is in India! Before the neo-Buddhist movement, the level of Buddhist practice in India was virtually nil.

Insightful as always. One of the interesting connections that outsiders might not notice is the way in which American Christianity has gone sideways in the two aspects which you distinguish as Hindu: individual purity and devotional rituals over theological dogma. Theology plays almost zero role in the life of the average zealous Christian in America. Praise and worship music + living "pure" is most, if not all, of what it means to be a Christian nowadays. This is not what Christianity was for thousands of years. Receiving blessed bread and wine from a priest is what it meant to be a Christian. What is considered "traditional" in America today--heartfelt devotion as a method of personal purification, primarily accomplished through long singing sessions where devotees sing repetitive songs that circle endlessly--basically became the default in the late 20th Century.

Important points. I have tended to find "Hinduism" a concept that obscures more than it reveals, though I wobble on that sometimes. (Why I Am Not A Hindu is a very helpful book.) I find that with complex concepts (whether or not they are ultimately helpful) it's usually good to go back to the concept's history - how did we get this word in the first place? - and "Hinduism" is no exception: https://loveofallwisdom.com/blog/2009/08/did-hinduism-exist/