The Great Books are a source of power

I continue to wake up at 5:45 AM each morning to read the Mahabharata. Last week I finished the third volume, which contains (amongst other things) a retelling of the entire Ramayana story. I also try to reflect each day on what I’ve been reading, just so I can organize and retain it somehow. And today I thought about how the Mahabharata is at least in part a guide on how to accumulate spiritual power.

Every powerful character in the book engages in austerities and prayers. Karna, for instance, will give a brahmin anything they ask for. When Indra appears to him in the guise of a brahmin and asks for the earrings and armor that make Karna invincible, Karna cuts them all away from his body and wins great fame and merit for himself (as well as the use of a weapon capable of killing Arjuna). The whole reason the Kauravas lose in the end is that their leader, Duryodhana, does not engage in austerities and pieties. He has more temporal power than the Pandavas, but much less spiritual power.

This was Gandhi's philosophy too. He believed that his side could win through spiritual power. The British had the guns, but they did not have right on their side. By purifying themselves and never engaging in wrong action (whether it was meat-eating, oath-breaking, sexual incontinence, or violence), he believed that his own side could strengthen their rightness and turn it into satyagraha (truth-force)—a power that would inevitably win out against their enemies.1

In this sense, satyagraha strongly resembles the magical weapon that Indra gives Karna as a result of his piety.

I think satyagraha is a very powerful and true concept. Over time, the side that believes more strongly in its own rightness is liable to prevail against that which doesn't believe. Look at the early Christians—they believed in their own religion. They believed they were going to rise again. They didn't have any warriors. They didn't have much riches. But they prevailed because the Romans didn't really believe in their own civic religion anymore—it'd become an empty set of rituals.

Similarly, I remember when all the tumult was happening on campuses about, say, speech codes and call-outs and whatnot. And professors would be like, "I live in fear of saying the wrong thing." But the professors had the power! They controlled the universities!2 They didn't have to listen to the opponents of free speech. But on some level, the professors didn't really believe in the worth anymore of what they were offering. And that's because many of these colleges genuinely weren't a good deal. They were charging undergrads too much for too little. And they were admitting too many grad students, all of whom hoped to become professors, and were exploiting these grad students for their labor, even as they knew that these students had little chance of getting permanent jobs.

Operating their institutions dishonestly had eroded the truth-force of these professors, so they were no longer able to genuinely say "No, this is an institution dedicated to truth, and we aren't going to fire or expel people for speaking unpopular opinions."

As a sidenote, this is why the University of Chicago has done so well during the free speech wars, because it has clear principles, and it trusts to its own worth as an institution and to the value that it provides to its students. They are very willing to outline the principles that direct their treatment of various forms of protest, and although their moves are controversial, they stick to them, because, ultimately, they claim that free speech is at the core of why they continue to exist as an institution. And people more or less believe them!3 Ultimately I think this will pay a lot of dividends for Chicago, and I would not at all be surprised if in thirty or forty years they’ve dethroned Harvard as America’s top university.

Reading and paying attention to the Great Books is a way of strengthening one's spiritual power. At some point, a God (Dharma) asks Yudhisthira what is supreme among riches, and Yudhisthira says "Knowledge of the sacred texts is supreme amongst riches." And I really do think that is true. I don’t think that the Great Books merely provide wisdom and consolation—I think reading them increases your own power to persuade people and to effect change in this world. Because when you read the Great Books, you are devoting yourself to something that has tremendous spiritual power.

I've been struck lately by how much practical gain has accrued to me from my knowledge of the Great Books. When I was starting out as a writer, I wanted to read the Great Books so I would become a better writer. I do think they've had that effect, but the ways they've made me better have often made me less salable. Because of the Great Books I know that there are ways to tell stories besides the highly-embodied, allusive, indirect style in vogue in literary fiction. As a result of those influences, my fiction often reads as poorly-written to editors or agents. So the Great Books have certainly led me away from my initial goal, which was to write well by the standards of my time.

But...because I have knowledge of the Great Books, I am able to argue in favor of other ways of telling stories. Because I have knowledge of books that people respect, I have a book deal with Princeton Press, and I have a Substack readership upon whom I'm able to inflict my own fiction.

People respect the Great Books. The narrative over the last forty years has been that the youth don't care about books by old white men or whatever. That they don't care about outside authority. They just want to tear it all down.

But I don't find that to be true. People want to be told that the sacred texts are worth studying. They don't necessarily want to study these books themselves, but they do not want everything destroyed and deconstructed. They are happy to hear that there is value here!

Books gain spiritual power because they have some connection to a living tradition or culture. As I mentioned in my world literatures post, one area where liberal academics have been very successful is in championing books by Black American authors. Even the most conservative school or university will read Martin Luther King or Ralph Ellison or Frederick Douglass. Everyone acknowledges that these writers have spiritual power.

The current politics of 'representation' has led to attempts to counterfeit that kind of power. A lot of people have tried to fashion themselves as the voice of some community or other (I'm sure you can think of examples), and over time their attempts tend to fail or fall flat. Which unfortunately leads to the idea that maybe representation itself is a counterfeit ideal. I don't think that's necessarily true, but I also think it’s not the job of the publishing industry to decide that someone "represents" some community. Nor does a community 'need' representation in the publishing world.

If a group of people is getting together and gathering as a community, then a literature will form. It might not be recognizable to outsiders as literature. It might not take the form of, say, stories that you can print in the New Yorker, but it will exist and it will have power because that group of people genuinely wants and enjoys it. Any group of people that's at all healthy does not really need Scribner or FSG to tell them who their real voice is.

The function of the critical, academic, and publishing apparatus isn't to invest objects with spiritual power, it's simply to recognize what things out there already have that power, and to discuss, criticize, celebrate, and disseminate them.

Personally, my task as a critic is relatively easy, because I don't need to convince anyone that the Mahabharata is worth reading. In contrast, if I was writing about The Americans, which is a show I'm watching now with my wife, I'd wonder, "Do I genuinely think someone should sit down and spend sixty hours of their precious life watching this undeniably-brilliant show?"

In my case, my wife likes it a lot, and it's bringing me closer to her—it's something to do together. So we're going to watch it. But I doubt I'd watch it on my own. If you're a critic who's writing about The Americans, what are you really doing?4 I guess you're recognizing that we as a people have chosen to invest a lot of our energies into television. And that this show is the most delicious fruit of that form. In the case of The Americans, I suppose I'm glad people take the time to write about television, because this is a show that only exists because of the critics! If it wasn't for critical acclaim, shows like The Americans wouldn't be made. And then I wouldn't have a great show to watch with my wife.5

Who knows? I guess someone has to write about TV. Someone has to perform that task of safeguarding and shepherding popular things.

For instance, during the Anglo-Saxon renaissance in the 10th-century in England, for some crazy inexplicable reason, a bunch of monks WROTE DOWN BEOWULF.6 Like, can you imagine? What the fuck did they imagine they were doing? Most of the time they're copying down, I dunno, Anglo-Saxon medical texts or some kind of spiritual material (there's a great Anglo-Saxon retelling of the book of Genesis)—these are things with a concrete, practical use. What in the world were they thinking when they copied down Beowulf? Like it must've taken, what…at least a thousand hours? They spent a thousand hours copying down this extremely pagan Anglo-Saxon epic poem. It's so different from anything else that we have from that era—it kind of staggers the mind—Beowulf is probably the oldest European vernacular-language literary work that exists. It's just so different from everything else that survives from that era—The Saga of King Hrolf bears a strong resemblance to it, but that's a work that was written down more than three hundred years later! In the tenth-century, nobody in Europe was writing down stuff like Beowulf.

Maybe some of these monks didn't think it was worth doing. Maybe they were like—this is in the local tongue, which is already an iffy thing to be copying down, and it's not even religious! This is just a story in the same vein as what the local storytellers have been telling for decades. Why is our abbot even telling us to do this?

In other words, Beowulf is the equivalent of TV.

I'm glad they took the time! I'm sure the Anglo-Saxon medical texts they otherwise would've copied (we have THOUSANDS OF PAGES of these texts) have their appeal, but in the long run I don’t think they’ve been of much value. There's also a very readable Anglo-Saxon translation of The Consolation of Philosophy. Supposedly it was translated by King Alfred the Great, but I think scholars agree that’s probably not true. For my personal purposes, this translation of Boethius has been much more useful to me than Beowulf has, because it’s a great intermediate Anglo-Saxon text, since it has a mixture of poetic and prose passages. I think Beowulf was rather archaic even at the time it was written, whereas with the Consolation of Philosophy, the intent was to be understood! It was a translation! The translator was trying to popularize and make accessible a much-older text.7

Probably the people who transcribed the Consolation of Philosophy text were like, "This is something people actually need and care about. A classic text whose wisdom people can use. Not, like...Beowulf, which is really just an entertaining story. Can you imagine those idiots spending all that time copying down Beowulf?"

Surely someone at the monastery must've thought copying Beowulf was an insane idea. It strikes me as ridiculous even now, so I'm certain other people must've felt the same.

Ultimately it comes down to persuasion. That's all it is. Someone persuaded someone else that Beowulf was worth keeping. Writing down Beowulf was the culmination of a long line of arguments. Someone persuaded someone else that the Anglo-Saxon language itself had value. Then someone persuaded someone else that we should write in and preserve it. Anything involving any kind of institution is just a continuous process of argument and of building on what's come before.

And in that process, the person who was certain they were right had a major advantage. I imagine it was just like everything today. There was basically a committee meeting—it looked different, but it was a committee—and someone had to argue forcibly in favor of copying this text. It was a person who'd devoted their life to letters, and when they said this one thing had value, other people believed them.

Nota Bene

I don’t usually read books people send me, because…I don’t usually read even the books I buy for myself! Like seventy percent of the time when I buy a book, I never read it, so how likely am I to read a book that I didn’t even choose to buy?

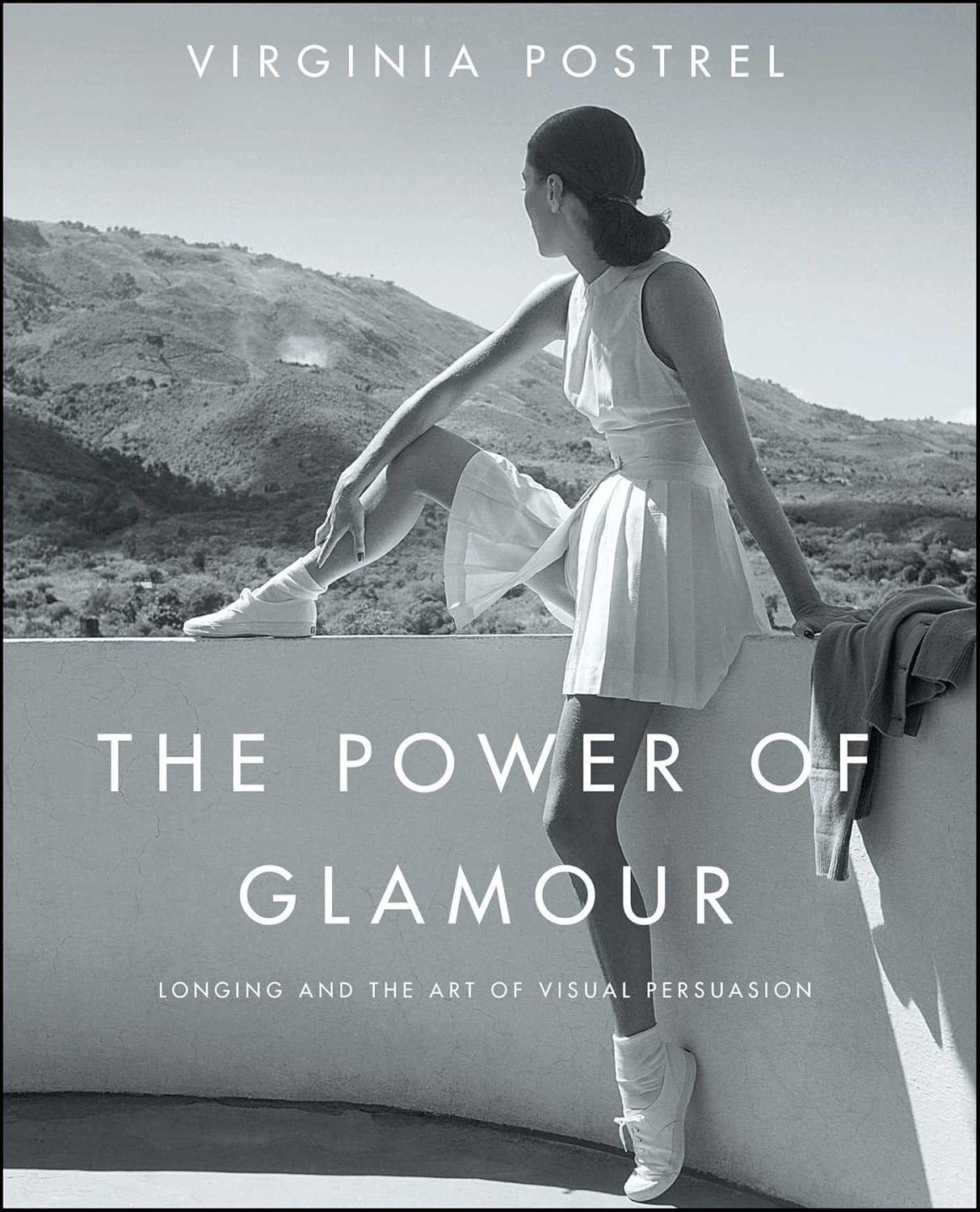

But Virginia Postrel for some reason sent me her nonfiction work The Power of Glamour, and I happened to glance at the first page after I’d opened the envelope, and I was hooked! I read the book over the course of a day—a Saturday, at that, which is normally quite a hectic day for me. It helps that the book is beautiful, printed in full color, with glossy images. I mean you’re essentially looking at pretty ladies and nice clothes and fancy houses, which is just an inherently diverting to do.

The book is quite unlike anything I’ve ever seen—it’s a treatment of the visual rhetoric of glamour. The history of glamorous images, and the way that they function for the viewer—how glamour often works by creating a sort of empty or null viewpoint figure (e.g. a woman with her face concealed or turned away) and allows you, as the viewer, to situate yourself inside the glamorous image. I think the key insight was that glamour is primarily visual. It doesn’t even operate at the level of the concept: glamour is pictures. It’s about imagining ourselves inside certain vistas or in certain situations. It sounds obvious, but when you stop trying to turn glamour into a story or into a concept, then you’re freed up to really analyze how it works. And the inclusion of so many pictures in the text allows you to see the truth of what the author is saying. You can literally follow your own eye as it does the things she’s talking about.

Advance Copies and Blurbs

Although I’ve allowed people to send me books in the past, I’ve recently changed my policy. Ever since my Greenwell review I’ve had a few people want to send me ARCs. I don’t really review books, honestly.8 If you’ve written a book you think I’d be interested in, please send me a direct message or email and give me a link to the book’s page on Amazon. If I like the way it looks, I’ll preorder or buy it myself (I’ve already done this several times). That way you get at least one sale, and I don’t have to feel bad about taking up one of your free copies. I treat free books the same way I treat all my books, which is to say, I might read them today or tomorrow or in fifteen years (or never). I had a copy of Midnight’s Children that my middle school history teacher gave me (in middle school!) that I finally read on vacation in India when I was twenty-four. I have a copy of The Hours that a friend gave me ten years ago. He died! I cannot give it back—I still haven’t read it. But I will someday, I imagine.

It does occur to me that someone out there might want my blurb. Believe me, my blurb does not sell books or impress anyone, and it is utterly meaningless in every sense—the only function of my blurb is that it might make you as the author feel better, like your book isn’t coming out totally alone and unloved. But obviously that’s reason enough to do it! So if you have a small-press literary novel or nonfiction book coming out and you want my blurb, please feel free to email me and tell me about it.

I wrote about Gandhi (and how he’s an incredible writer) in a previous Substack post.

Professors will sometimes say, “But we don’t control this institution! The administrators do.” Well…but isn’t that just another way of saying you operated this institution dishonestly? You allowed control of it to slip away, because it was expedient. I’m not saying any one person was at fault, but somewhere along the way, the institution became dishonest, and this is the result. I wrote about this a bit in a previous post.

Henry Oliver recently had a paid post about how Succession isn’t King Lear. I’m not really that sure, myself! I certainly would not want to spend my time arguing that Succession is great art, but I did enjoy the show quite a bit, and I do think it should probably be someone’s job to figure out which shows are worth preserving! But, honestly, it seems like time will tell. If people are still excited by Succession in twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, or a hundred years, then we’ll know that it was great art! Right now the only TV show I can think of that really excites people in a way reminiscent of great art is Twin Peaks (which I’ve never watched).

I’m aware this take comes off a bit dated, because TV viewership is down these days, and it’s been replaced by even more hyper-stimulating and mindless forms of entertainment (i.e. TikTok. Twitch, Youtube, etc), but…just because worse things than TV exist, that doesn’t mean that TV itself isn’t bad. I’m sure someone here will chime in with a comment about how the ancients weren’t that sanguine about reading, either. But hey, maybe they were right about that! If my choice was between talking to Socrates or reading a scroll, I’d probably say that talking to Socrates was the superior pursuit! If talking to Socrates was an option in this day and age, then that would definitely be the thing we should all be doing. Talking to Socrates seems like a very stimulating activity! This is not something we only know from Plato, by the way. A number of Socrates’ students wrote about him, although the only other account that survives is from Xenophon. His work isn’t really a work of philosophy—it’s basically just a memoir about spending time with the actual, historical Socrates. He makes it sound great. This was obviously a pretty interesting guy. On the other hand, the impression I’ve gotten is that Socrates was: a) not particularly physically attractive himself; and b) somewhat lecherous in his feelings towards many of his students. So I’m sure to a lot of people talking to Socrates was quite an unpleasant experience! I mean…they did put the guy to death basically for the crime of being annoying. So that kinda tracks, right?

I realize I’m using ‘Renaissance’ incorrectly, because it implies a rebirth, but fundamentally the English, French, and Italian Renaissances (in literature) were about the rise of the vernacular as a literary language—this is a process that had already occurred in Anglo-Saxon England beginning with the reign of Alfred the Great, before terminating abruptly with the Norman Conquest. Actually, Anglo-Saxon civilization was reborn after England was almost conquered by the Vikings in the 9th century, so I guess the term is appropriate.

I’ve still not read Beowulf in the original! I’ve read a translation once, and I read it again as a graphic novel. But look, even for me, a person very interested in Anglo-Saxon literature, the Beowulf text has limited utility! At the same time, the existence of Beowulf as a text surely anchors Anglo-Saxon’s entire existence as a literary language. If Beowulf didn’t exist, I likely wouldn’t even have bothered trying to learn the language. I certainly intend to read it in the original at some point, but who knows if that'll ever happen.

On a personal level I’ve soured on the practice of sending advance copies. I’ve published four novels, and for most of my books, the worst reviews I’ve gotten have come from bloggers who got advance copies for free. It’s okay to hate my book, but I feel like people should at least pay for the privilege.

Very much enjoyed this discussion of the spiritual power of art. It's nice to see someone argue for something like this rather than some sort of practical or utilitarian benefit of art, but it's also a challenge, because how do you talk about the spiritual convincingly in the contemporary world? As I was reading I kept thinking of the idea of faith, which I think is what you were getting at when you talked about people believing in the value of their own work. I don't mean religious faith here, just a belief that what you're doing matters, that it's the right thing, even if you have no real proof, or no proof that could be recognized as such by others (one can see how this can go wrong, too). The person who I think captures these ideas of faith and spirituality, at least imo, is Andrei Tarkovsky, and I find myself returning to his films and writing again and again. I'm just gonna include a quote from his book "Sculpting in Time" because it's full of this sort of stuff:

"Art addresses everybody, in the hope of making an impression, above all of being felt, of being the cause of an emotional trauma and being accepted, of winning people not by incontrovertible rational argument but through the spiritual energy with which the artist has charged the work. And the preparatory discipline it demands is not a scientific education but a particular spiritual lesson..."

My issue with The Americans was that the strengths of the show (the acting, the physical and social mise en scene, the portrayal of FBI and Sovet bureaucracy, the slow burn of the underlying dramatic situation, especially as regards the children, etc.) went along with some wildly overdramatic made for TV storytelling. Philip and Elizabeth were assassinating people every other episode it seems like, were personally handling wildly toxic biological weapons, etc. etc. They were a one-family crime spree in a way that is optimized for television but not for a deep cover agent. In the end I had a hard time suspending disbelief even though the way the setting was handled was masterful.