What do I mean by "The Great Books"?

I actually mean a list composed by two old white English professors and published in 1999

The most common question I get when telling people I’m writing about the Great Books is “What do you mean by ‘The Great Books'?”

It’s a question I initially found confusing and perplexing. I’m like, “you know, Aristotle and Plato and Shakespeare and Milton and all the super-classics that you hear about but never read. “

But some people have no idea what I’m talking about. They’re like…”mmm…okay?” This room just does not exist in their brain. They never had any concept of “Western Civilization” or “The Great Conversation” or even “The Canon”. They understand that some books are old and were held to be quite important, but the notion of a concatenation of all the great authors from throughout time and space, all in conversation with each other, is not something they understand. Nor are they familiar with the idea that you can overhear and eventually participate in this conversation.

That’s the first reaction. The second reaction I sometimes get, equally puzzling, is that they want to know what books I specifically mean. What books am I talking about? What are their names?

This is more understandable, but it’s also a bit perplexing. Like, do the details really matter? You can quibble about the names, but I’d think any reader could draw up a list of Old White Guys in about twenty minutes: Sophocles, Aeschylus, Euripides, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Herodotus, Cicero, St. Augustine, Descartes, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Milton, Austen, the Brontes, Dickens, Whitman, Melville, Dickinson, Tolstoy, Gogol, Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, Rousseau, Flaubert, Voltaire, Stendhal, Balzac, Henry James, Willa Cather, Edith Wharton, Faulkner, Hemingway. That’s about a third of them, and I listed them in ninety seconds.

When I talk about the Great Books I’m generally not that concerned with the specifics, and more with the difference between these books and the contemporary books we normally see discussed in review pages and book clubs. But people insist on wanting to know the specifics. Partly, I think, for racial and gender equity reasons: out of the folx I listed, I think there are five women. And all are Western. My definition for the Great Books includes a lot of non-Western works, but it’s still heavily tilted towards the male and the West. To me that’s implicit in the idea of the Great Books. You can’t really make them diverse and representative, because we’ve only preserved written literature from a few societies, and in most of those societies women had structural disadvantages that prevented them from writing great literature and prevented their literature, even when it was great, from being preserved.

But getting all these questions has made me realize I really do need to be more specific about exactly which books I mean.

And that’s fine! In fact I realized after reading Eric Adler’s fantastic Battle for the Classics that more often than not proponents of “culture” like to keep mum about exactly which books they want everyone to read. This is true of both right-wing and left-wing polemicists. Allan Bloom, for instance, spends five hundred pages bemoaning the fact that students aren’t reading the right books, but, crazily, never tells us which books they ought actually to read.

That’s because getting caught up in specifics is dangerous. To say that students should read more classics or engage with more “high” culture is unobjectionable. But the more manageable and readable the list is, the more objections it raises. For instance, if you were to say every American ought to read Paradise Lost, Anna Karenina, The Social Contract, Moby Dick, and the poetry of John Donne, you’d look foolish. Why these specific books? Why Moby Dick and not The Ambassadors? But if you start broadening your list, then you’re suddenly including books that are very hard to read (e.g. Plato’s Timaeus or Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit) and books that are very long (e.g. Thucydides or Herodotus’s Histories). This is an inescapable problem: the most important books in Western civilization are much too difficult for most people to read, and it’s much too difficult for any one person to read and understand all of them, unless they’re a rather exceptional person. Thus, the Great Books program either founders under its own lack of realistic potential as an educational program, or, in restricting itself to a relatively small number of readable texts, the program loses its grand claims to being inclusive of the world’s greatest authors and becomes much less conceptually exciting.

But if reading the GBs is unrealistic, how do all those erudite New York Review of Books types learn to pepper their essays with so many references. Well, I’ve realized most people tend only to read the GBs that are germane to their field (if that) and then a sprinkling of others that catch their interest. For instance, a literary writer might attempt the Russians. A cultural commentator might read Max Weber and Thorsten Veblen. A conservative intellectual will almost certainly read Plato. But almost nobody is reading the Greeks AND the Russians AND Kant AND Hegel AND Milton AND Shakespeare. And if they are, then they’re likely a freelance intellectual like myself (established intellectuals have too many reviewing, teaching, research commitments to spend their time on a far-reaching GB reading program).

So this brings us back to the question: What do you mean by “The Great Books”? Why did you try to read them? And why do you evangelize for them?

The answer to the second question is something I tried to answer in the essay for the LA Review of Books that led to my getting the book deal with Princeton Press: essentially, I thought that I was supposed to. I thought that if you wanted to be a writer or thinker in the US, you needed to read all these books.1

To summarize, my entire middle- and high-school education at the St. Anselm’s Abbey School (a Benedictine school in Washington, DC) was suffused with the idea of the Great Books. Starting in 6th grade we learned Latin. Before middle school ended, we were translating Cicero. Whether it was in Latin or Church History or English or European Civilization class, we were inculcated with the idea that there was a great tradition of learning that we were heirs to.

But, in a much more specific sense, I imbibed the idea of the Western Tradition and the Great Authors in Dr. Downey’s year-long Humanities class in 10th grade, which, as far as I can remember, began with Petrarch and ended with Italian Futurism (which, in retrospect, seems like an insane breadth of coverage).

Due to this education, I was primed, when I later wanted to fill in the gaps in my own education, to think that I ought to go back and read all the old books I’d never read before.2

But, on a broader level, where did Dr. Downey get the idea to have a class like 10th-grade Humanities? Why did our Catholic school decide that an education combining secular Latin writers (Cicero, Vergil, Catullus, and Ovid) with Greek Philosophers (we read The Nicomachean Ethics in our Christian Ethics class), 19th century novels (Pride and Prejudice in 10th grade, along with the usual Shakespeare across various years) and modern classics (I recall Black Boy, Animal Farm, Brave New World, and Cat’s Cradle, amongst others).

This is not how high school was traditionally taught either in America or in Britain. Typically, the main focus of British secondary schools was to prepare one for a university education. The main focus was on Greek and Latin, almost to the exclusion of all else. You could enter Oxford or Cambridge as soon as you could test into them, and students as young as fifteen could matriculate (this was also true of early American colleges). Serious reading happened in college. Moreover, the reading in college was almost entirely in Latin and Greek: until relatively late in the 19th century there was little focus on the English classics.

At the same time, Protestant dissenters were barred from the Oxbridge schools and from the major English secondary schools, so they formed their own network of educational institutions that primarily taught the English classics (they didn’t have the skilled instructors to teach Latin and Greek, nor could their students utilize Latin and Greek, since they were barred from higher society). This dual-track model continued in America, where only something like 3% of high schools in the late 19th century required Greek and Latin, but all the oldest and most prestigious colleges had Greek and Latin requirements.

The canon of English classics (e.g. Shakespeare, Milton, Johnson, Dryden, Wordsworth, Coleridge, etc) developed primarily due to the demands of vernacular-language high schools. My understanding is that novels weren’t considered worthy of study, so even at this time most of what we’d consider the 19th century classics (Middlemarch, David Copperfield, etc) were not studied. Some colleges might teach French and German (Harvard did, Yale didn’t), but all reading was done in the original. Classics in translation weren’t taught, and oftentimes English translations were out of print or didn’t exist.

This meant education was either in Greek and Latin classics or in English language poetic, dramatic, historical, and philosophical works.

So when did everything get collapsed together into the unholy melange that St. Anselm’s Abbey School adopted?

Enter: The Great Books movement.

The funny thing is that a movement dedicated to recovering our intellectual heritage—a movement that prides itself on attention to tradition and on the long lineage behind its choices—is itself ahistorical.

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that the idea of a trans-historical, cross-cultural canon developed. Matthew Arnold most famously recommended culture, in the abstract, as our bulwark against anarchy, writing:

The whole scope of the essay is to recommend culture as the great help out of our present difficulties; culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world, and, through this knowledge, turning a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits, which we now follow staunchly but mechanically, vainly imagining that there is a virtue in following them staunchly which makes up for the mischief of following them mechanically.

But it’s one thing to recommend “The best which has been thought and said in the world”. That’s pretty uncontroversial. It’s another thing to define what exactly that is.

Which brings me around to the initial question: “What do you mean by the Great Books?”

The first attempt to define and publish the Great Books was at the beginning of the 20th century from Harvard President Charles Eliot, who developed his five-foot (later six-foot) shelf on the thesis that an American workman, reading fifteen minutes a day, could read all the classics of Western civilization (in English translations) in ten years. Ironically, Charles Eliot was the person who reformed the educational system at Harvard, replacing the fixed curriculum with electives and a system of majors, and dropping Greek and Latin requirements. Before he came on the scene, the education at Harvard was famously tedious: one of the sophomore year requirements was that students learn to recite, by memory, twenty chapters of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

The second set of Great Books evangelists arose in response to Eliot’s educational reforms. John Erskine at Columbia developed the Core Curriculum: a study of the Western classics (in translation) that is still a major part of Columbia’s curriculum today. The innovation was not popular with the faculty. Nobody wanted to teach translations: the Classics, French, and German departments all felt that teaching literature in translation was not a worthwhile activity, and that it was equivalent to not reading the literature at all. What’s notable here is that relatively few people could read Greek AND Latin AND French AND German to a level needed to read all the relevant classics: before dropping its language requirements, Yale’s required curriculum (all students took the same classes) didn’t even include French and German.

And this was by far the most common critique of the Great Books curriculum, as envisioned by Erskine and later by Robert Hutchins and Mortimer Adler at Chicago. Not that it was too elitist, but that it was too democratic. It covered too much. It was ahistorical (F.R. Leavis) and middlebrow (Dwight MacDonald).3 For a time in the 50s and 60s, the Adler / Hutchins Great Books of the Western World sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and at the peak of the movement, fifty thousand Americans were enrolled in Great Books reading groups. But by the end of the sixties, sales had cratered: one issue was that the print was small, the books had no footnotes, the translations were outdated, and many of the selections were fairly esoteric (for reasons that are still unclear, Adler and his colleagues insisted on including “classic” works of science, like Appollonius of Perga’s On Conic Sections).

Long before all the current hullabaloo about the classics and about whether the Old White Men (OWMs) are racist, the idea of a classical education had died not once (with the abolition of Harvard’s Latin and Greek requirements) but twice (with the increasing disinterest in the Great Books movement). What is at stake today when people debate “liberal education” or “the canon” is not any specific educational program, but a highly abstract idea about whether modernity—the various economic, social, and technological achievements that made the 20th century different (and, frankly, a lot more pleasant) than previous eras—can be directly traced to some unique endowment of culture from the past. Some argue that we became modern by jettisoning ancient wisdom; others argue that modernity was only achieved by embracing lessons from the Great Authors. (And, of course, some other people argue that modernity is bad, but let’s leave them aside for now). What’s at issue in this discussion isn’t peoples’ reading habits, but their assumptions about modernity. Very few people involved in this debate seriously think that an ordinary person is going to sit down and read Kant.

Incidentally, I don’t think that either! What I think is that if you want to read Kant, you’re probably not ordinary! I don’t think about the Great Books from a social engineering standpoint. I am not concerned with constructing an ideal education or an ideal society. My question is: if you’re an intelligent person, who is seeking wisdom and some sort of truth about the human condition, what ought you to read? And I think that the Great Books program provides a very good answer!

You don’t have to read them all. There’s no checkbox, there’s no test. I haven’t read half the books myself.4 I just think that by now, at this point in 2023, the Great Books program has attained a historical status. And, frankly, there isn’t another equivalent course of self-directed reading that a person can readily follow. The choice isn’t between reading the Great Books and reading some other set of extremely diverse and equally productive classics. There is no set of one hundred demographically and racially representative classics that you can pick up. The Great Books program works precisely because so many of the names are familiar, and there is so much agreement about the merits of at least half of the list.5 Yeah you don’t have to read Hume or Locke or Kant or Fielding or Richardson or Austen or Tolstoy to be educated, but if it’s a choice between picking up those books or some NYT notable book published last year, you probably can’t go wrong with the former!

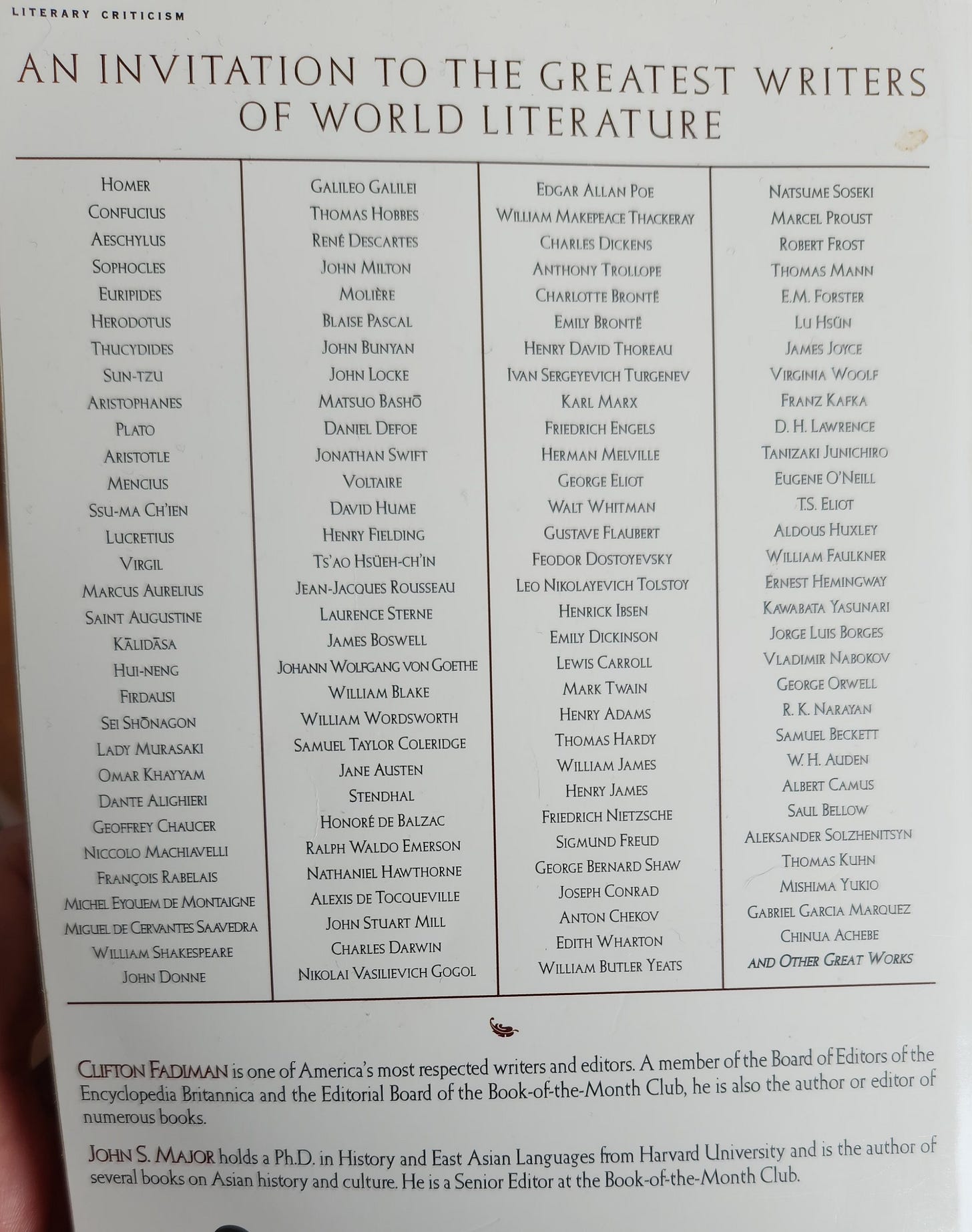

Okay, now, the question remains: What books do I specifically mean? And here the final wrinkle is that when I personally talk about the Great Books I am not talking about either Eliot’s version or the Adler/Hutchins version. I am instead talking about the version put together by Clifton Fadiman and John Major in 1999. Fadiman, who had worked with Erskine at Columbia and was a bit player in the Great Books movement, put out several editions of The Lifetime Reading Plan between 1940 and 1990. His was a version of the Great Books program that was tilted more towards readability (no Hegel) and that had more novels, fewer philosophical works, and more twentieth-century works. But in the late 90s he and his colleague John Major decided to put together a version that would also contain Great Books from East Asia, the Middle East, and South Asia. I didn’t know at the time how rare this was! I picked up the book because it was recommended at a panel (at a sci-fi convention, Readercon) by Michael Dirda, the Washington Post’s book critic.

I’m extremely thankful that I chose this particular edition of this particular book. It’s because of this book that I’ve read Dream of the Red Chamber, Pillow Book, Tale of Genji, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, R. K. Narayan, Junichiro Tanizaki, Yasunari Kawabata, Natsume Soeseki, Confucius, and others from East and South Asia. Because of this list, when I think about “The Great Books” I don’t see the term as having a western bias. Nonetheless, as you can see, even this list is mostly composed of Westerners. To my mind, the Great Books has this bias just because it’s a book made in English, for English-speaking Americans. It’d be weird to expect a Chinese person to read Beowulf, but it’d be equally weird if an English-speaking person left it off their list. Not every book is equally important for every culture.

There’s a lot more to say about where this list comes from, and how it was made, but at the end of the day, when I say “The Great Books” I mean the selections from this book”.6

Further Reading:

The best popular nonfiction book on this subject is Alex Beam’s A Great Idea At The Time, about the GB movement. I’ll need to write a separate post about this one sometime.

Eric Adler’s Battle of the Classics is where I got most of my notions about the development of the American educational system. Another highly readable book, even though it’s by a scholar.

Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind is still the classic “These kids don’t read good books today” polemic. Memorable especially for long tirades against rock music and multiculturalism. I have a soft spot for Bloom because of the loving portrait of him in Saul Bellow’s best and least self-indulgent novel, Ravelstein. Bellow, by the way, is the most famous author associated with the GB movement: he helped compile the index to the 1952 Adler/Hutchins Great Books set.

And, of course, my still-favorite list of GBs: Clifton Fadiman and John Major’s New Lifetime Reading Plan.

Upcoming:

Thank you to the huge number of people who’ve signed up! This Substack has only been in existence for one week, crazily enough, and it’s getting 10x the viewers that my Wordpress site was getting. To anyone else who’s considered switching, you absolutely must. My next post will be a shorter one about Nietzsche and the resonances between his thought and that of an Indian epic, The Mahabharata.

Then I’ll also write my first paid post, which will be about On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and the infuriating dualism of Ocean Vuong’s writing (whenever he tries to write well, he’s awful, and whenever he tries to write plainly, he’s great!) Unfortunately his mistakes have been replicated ad nauseum lately, and they’ve become one of the tics by which PoC writers display “talent” and gain attention of the publishing industry. The post will, hopefully, be less of a critique and more of an exploration of the way that the demands of the publishing industry shape what kind of fiction gets purchased and extolled.

As a PS, my last newsletter went out with a huge typo in the first sentence (since corrected in the online version). Sorry about that. I am used to writing for free, and the addition of a paid option has me worrying more over the presentation of the blog. Will try to proof-read more in the future.

I know much more now about the Great Books and the development of the English and British education systems than I did when I wrote the essay, and if I was rewriting it, I’d clarify the complexity of the 19th century educational system, and the differences between secondary and college education. But I stand by the basic conclusions: reading the Great Books for pleasure has never been an elite activity in the way conceptualized by myself and the Great Books program and my Catholic high school.

Sometimes I think that what Allan Bloom was arguing for, in his Closing of the American Mind was not for genuine engagement with the classics, but for the continuation of this priming effect. He wanted college students to venerate the Great Books even if they didn’t read them. He seemed, at times, to view college as the last time a student might be truly alive, before they were lost to trade or the professions. It was a very Platonic view of humanity and very at odds with the democratic spirit of the GB program. As he puts it: “What image does a first-rank college or university present today to a teen-ager leaving home for the first time, off to the adventure of a liberal education? He has four years of freedom to discover himself—a space between the intellectual wasteland he has left behind and the inevitable dreary professional training that awaits him after the baccalaureate. In this short time he must learn that there is a great world beyond the little one he knows, experience the exhilaration of it and digest enough of it to sustain himself in the intellectual deserts he is destined to traverse. He must do this, that is, if he is to have any hope of a higher life.”

Leavis, “A man will hardly justify time and energy spent in reading the works of Aristotle (to take one instance of the many presented by the Great Books) unless he is committed to an intensity of sustained frequentation, and to a study also of the works of the relevant specialists, that will make him something of a specialist himself. Mr. Hutchins and his friends, in fact, have not formulated the problem of liberal education as it presents itself today to anyone who proposes really to grapple with it. We are irretrievably committed to specialization, and no man can master all the specialisms.” MacDonald, “In its massiveness, its technological elaboration, its fetish of The Great, and its attempt to treat systematically and with scientific precision materials for which the method is inappropriate, Dr. Adler's set of books is a typical expression of the religion of culture that appeals to the American academic mentality.’

One suspects most of the vituperation against the Great Books came from critics and intellectuals who were angry at the assumption that they were poorly read because they hadn’t read the Great Books. Both MacDonald and Leavis freely admit that they haven’t read Aristotle, for instance. Hey, I haven’t read him either (aside from Poetics)! What’s funny is that even Hutchins and Adler hadn’t read a few of the Great Books that they included in the list.

MacDonald, “THE wisdom of the method varies with the obviousness of the choice, being greatest where there is practically no choice; that is, with the half of the authors -- by no means "the overwhelming majority" -- on which agreement may be presumed to be universal: Homer, the Greek dramatists, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Virgil, Plutarch, Augustine, Dante, Chaucer, Machiavelli, Rabelais, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Bacon, Descartes, Spinoza, Milton, Pascal, Rousseau, Adam Smith, Gibbon, Hegel, Kant, Goethe, and Darwin. A large second category seems sound and fairly obvious, though offering plenty of room for discussion: Herodotus, Lucretius, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, Tacitus, Aquinas, Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Swift, Montesquieu, Boswell, Mill, Marx, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Freud.

Although not included in this book I do tend, at least privately, to lump a few other works and authors (Kant, Hegel, Plutarch, Gibbon, amongst others) into “Great Books” category. And sometimes when I talk about the “The Great Books” I really just mean “any old book” or “any book in the canon”. As one of the GBs put it, Do I contradict myself? Very well, then let me contradict myself: I am large, I contain multitudes.

Nuanced and thorough -- appreciate this immensely. I was going to say that I was glad that Austen, the Brontes, and Cather made it into your list of Old White Guys, but I see that you've qualified that :). I agree that one can't simply ignore these works, given the imbalanced methods of textual preservation. However, when I taught American literature, I preferred the Heath Anthology model of expanding the canon. For instance, it's true that many of the voices of colonial America were white and male (Winthrop and Bradford), but it's also true that there was a rich literary tradition in North America long before European settlement. My objection with some approaches to literary studies now is that they tend to replace Winthrop and Bradford entirely with voices that formerly were marginalized. To me it's much more interesting to place Genesis 1:3 alongside, say, the Seneca tale "The Origin of Stories" or the Lakota story, "Wohpe and the Gift of the Pipe." And I also enjoyed teaching non-traditional texts like the transcript of Anne Hutchinson's trial, which is the only record I know of that preserves her inimitable voice, alongside classics like Winthrop's "A Model of Christian Charity." It's unfortunate that our current culture wars often pit zero sum arguments against one another. Mary Louise Pratt's idea of America as a "contact zone," where competing ideologies clash and grapple for power, is still useful, IMO.

As someone who loves weird platonism and whose primary non-novelistic/literary or 19th-20th philosophical readings from the GB tradition is the Platonic corpus I've always been fascinated that they included an abridged Plotinus in the 50s/60s edition of the great books. I guess it had to be there for completeness sake but it always raised the (to me comedic) image of some upper middle class brat having their mind blown by the undescended soul.