This literary genre was dropped from the canon. But maybe it had something to offer.

Recently I introduced a friend to Dwight MacDonald’s 1960 essay “Masscult and Midcult”, and she was beyond horrified by the snobby tone. She couldn’t even finish it.

My friend is younger, and she didn’t know that this essay was extremely influential for my generation of literary critics. The essay was reprinted by the NYRB Classics in 2011, and it’s very clear that many millennial literary critics read that reprint volume and absorbed these ideas about middlebrow culture.

In this essay, MacDonald claimed that in the last two centuries there had arisen a mass-produced culture that was a bastardized version of high culture. And he described this mass culture in extremely demeaning terms:

Masscult is bad in a new way: it doesn’t even have the theoretical possibility of being good. Up to the eighteenth century, bad art was of the same nature as good art, produced for the same audience, accepting the same standards. The difference was simply one of individual talent. But Masscult is something else. It is not just unsuccessful art. It is non-art. It is even anti-art.

He won’t even allow that Masscult is the expression of some genuine artistic impulse on the part of the masses. According to MacDonald the true art of the people is Folk Art, and Folk Art has a basic honesty that's missing from Masscult. That's because Masscult is not really the art of the people, it’s an art produced for the people.

…The separation of Folk Art and High Culture in fairly watertight compartments corresponded to the sharp line once drawn between the common people and the aristocracy. The blurring of this line, however desirable politically, has had unfortunate results culturally. Folk Art had its own authentic quality, but Masscult is at best a vulgarized reflection of High Culture and at worst a cultural nightmare.

Although he doesn’t use the term in this essay, he’s talking about the middlebrow—a concept that is summarized by Phil Christman in a very comprehensive essay for The Hedgehog Review. As Christman puts it, MacDonald believes that “an ersatz culture, aimed at the half-educated, is crowding out the real thing.”

And I have to say, this concept of the middlebrow—stuff that was made for a mass audience, and which was supposed to be smart and elevating, but was actually bad—I found this conceptto be very attractive in 2014 or 2015, when I first read this essay, because I could perceive that lots of people were extolling books that weren’t actually good.

But sometime in the last decade I decided that calling a book ‘middlebrow’ is boring and unproductive. Because first of all, if you’re going to call something middlebrow, you’ve often got to explain the concept of middlebrow to people. And now you’re bogged down in this long discussion about this category of thing, and you haven’t even gotten to the central point, which is that you don’t like the work of Rachel Kushner.

Moreover, while everyone can agree that there are popular things which are overrated, in practice people tend to disagree about what those things actually might be. Thus, talking about the middlebrow becomes a very long way of avoiding actually having conflict with someone who might have different opinions with you about stuff. Many people might agree that the middlebrow exists, but that doesn’t mean they hate Sally Rooney or Ocean Vuong or Rachel Kushner or whoever it is that you happen to dislike.

Dwight Macdonald faced this same problem himself! He originally wrote “Masscult and Midcult” for The Saturday Evening Post. The editors of that journal pressed him to list The New Yorker as an example of Midcult—something between Masscult and High Culture, which is even worse than Masscult, for reasons MacDonald explains at length. He refused, because he did not think The New Yorker, where he often wrote, was Midcult—in part for this reason, the Post did not print his essay and he published it in a journal with a much smaller circulation, The Partisan Review.1

In my life I have definitely toyed with calling certain things ‘middlebrow’. Like I said, this essay was very influential for people like me. But I tend not to use the term today, purely because it doesn’t strike me as being very rhetorically effective.

Let’s quit judging the middlebrow and start describing it

However, there’s also been an attempt over the last thirty years, at least in academia, to rehabilitate the idea of middlebrow. Some academics argue that there was a distinct middlebrow culture, and that this culture had its own canon, its own aesthetic criteria, and its own tastes.

This line of criticism takes seriously the MacDonald taxonomy, which divides art into Folk Art, Masscult, and High Art, but it takes away the negative emotional valence. If Masscult exists, then let’s study it. What are its themes, its traditions, how was it understand by its own audience? As a result, there is now a thriving group within humanities academia that studies middlebrow culture. One of the stated aims of this group is to:

To examine whether there is such a thing as a ‘middlebrow aesthetic’ in literature, the arts and entertainment. If so, to analyse its relationship to prestige and popular cultural movements, to processes of canon formation, and to class hierarchy and discourses of taste.

This group tends not to make value judgements. It doesn’t seek to rehabilitate its objects of study and say, oh actually these books are great. Instead it’s mostly descriptive–it aims to quantify and describe, without judging.

However, there are also at least a few literary critics who’ve argued that the middlebrow is a category of literature which has aesthetic value, and which a person should consider actually reading. Rich Horton is someone who’s always in my comments talking about how maybe ‘middlebrow’ is more than just an insult. Maybe there are good middlebrow novels that one can enjoy reading because they embody aesthetic properties that only middlebrow literature has developed to their highest level.

I have been somewhat resistant to this notion. My feeling is that if something is good, then it’s good. For instance, MacDonald derided H.G. Wells as “Masscult”, but actually he’s just good. H.G Wells was a highly-acclaimed, highly-influential writer for a reason, and that’s the same reason that he remains beloved today. Because his novels do whatever it is that good novels ought to do.

The Middlebrow Aesthetic

But I am starting to come around to the idea that there is a variety of goodness that middlebrow books can possess, but which contemporary highbrow critics tend to be unable to recognize.

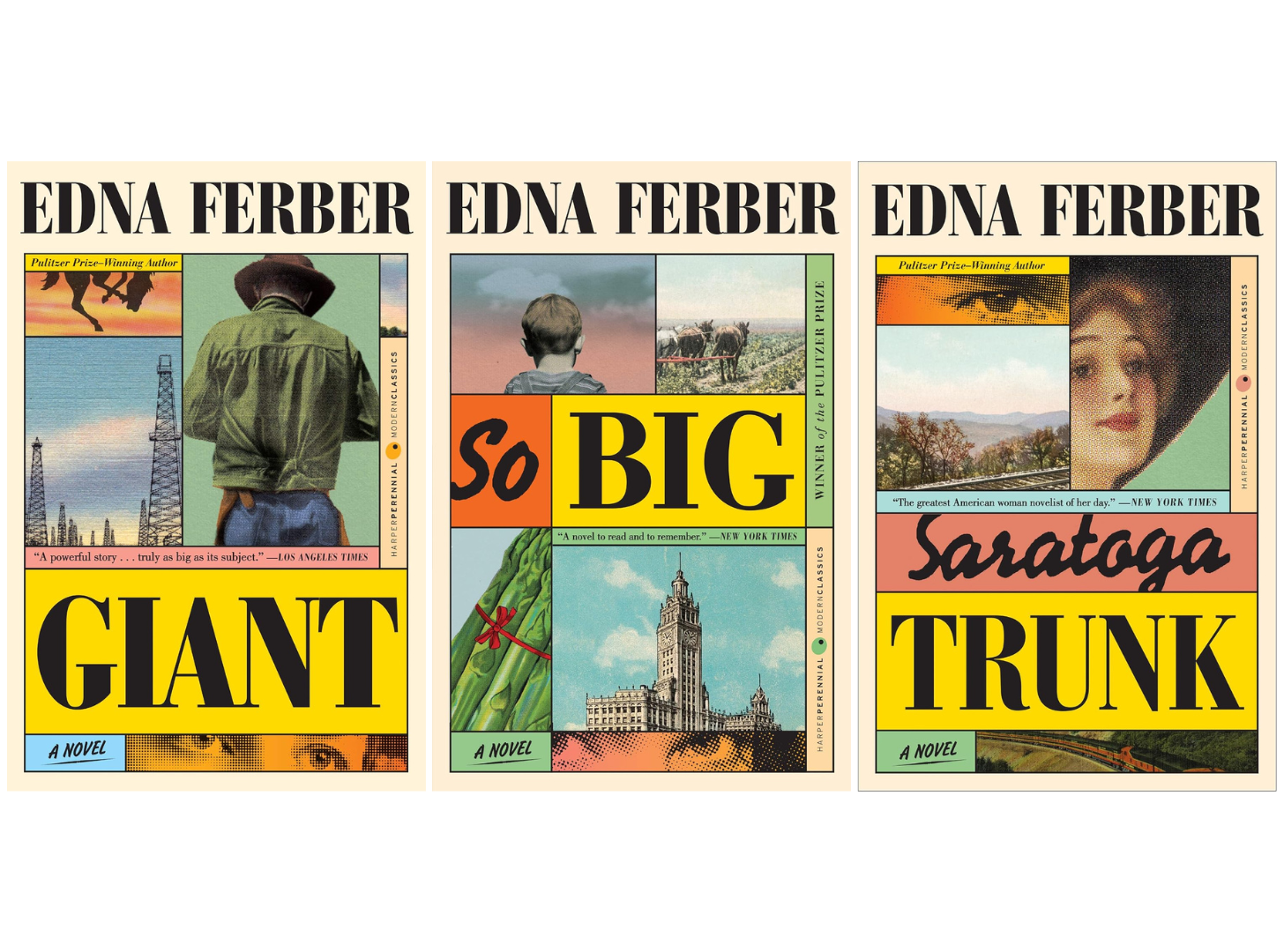

And that’s because, for the last two weeks, while I’ve worked on my nonfiction book, I’ve been reading the novels and stories of Edna Ferber, who was an extremely popular, highly-acclaimed novelist and playwright during the twenties and thirties. (She even had a late-career hit during the fifties with Giant.) For many decades, she was well-respected name in American letters.

Ferber was born in 1890 in Michigan, grew up in Wisconsin, and was the daughter of an unsuccessful storekeeper. Her family couldn’t afford to send her to college, so when she was eighteen she became a newspaper reporter. But then she got sick, and went home to recuperate. While she was resting, she started selling short stories to the sorts of popular periodicals I mentioned in my O. Henry piece, and for the rest of her career she supported herself by writing stories and novels.2

Aa her fame grew, she was increasingly derided as middlebrow—she is mentioned by name in the first paragraph of the MacDonald essay—but if you actually read her work, it’s not easy to dismiss.

For starters, I would not say that her work is overtly sentimental. Her novels are usually about women who marry a powerful guy that’s not quite right for them, and the resulting marriage could certainly be described as ‘troubled’, but the woman usually manages to find some fulfillment anyway.

Her best novel, So Big, was the top-selling novel of 1924 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1925. In So Big, you’ve got this woman, Selina, who takes a job as a school-teacher in a Dutch community in rural Illinois. This woman has no money, she’s the daughter of a disgraced gambler. And she gets romanced by this local farmer, Pervus DeJong, who’s a bit of a lummox:

He looked helpless as only the strong and powerful can look. Selina’s heart melted in pity. He would look down at the great calloused hands; up at her. One of the charms of Pervus DeJong lay in the things that his eyes said and his tongue did not. Women always imagined he was about to say what he looked, but he never did. It made otherwise dull conversation with him most exciting.

He is a bit slow. And he is poor. And he is not a great farmer. But…like…nobody else in this town was gonna marry her. Everyone in the town is a bit suspicious of Selina, who is a penniless outsider, whereas the lummox actually loves her.

Life with him is hard. She becomes a farm-wife, does farm-work. And what’s harder is that she has ideas about how to live a better life. Their land is not good. It needs to be improved, but her husband doesn’t see that—he wants to farm the way his father did.

Her husband, Pervus, has a lot of ideas about how their marriage should work. But he’s such a lummox that he doesn’t know how to be domineering and keep her in line. She has some money saved, and she begs him to switch up their crops:

“…Let me put my own money into it, I’ve thought it all out, Pervus. Please. We’ll under-drain the clay soil. Just five or six acres, to start. We’ll manure it heavily—as much as we can afford—and then for two years we’ll plant potatoes there. We’ll put in our asparagus plants the third spring—one-year-old seedlings. I’ll promise to keep it weeded—Dirk and I. He’ll be a big boy by that time.”

But in the midst of all this work, Pervus dies, and instead of renting the land out to someone else, Selina decides to farm it herself, which the neighbors think is insane. She takes a cart to the market to sell their produce, and it’s a terrible experience, nobody will buy from her. She starts to get a sense from one vendor of how she could perhaps create a business selling cabbage to fancy households and restaurants in Chicago, but…she’s going broke.

Luckily, she meets an old school-friend who’s now rich, and this friend’s dad gives her a loan, which Selina uses to improve the farm.

Then the novel starts to move at a faster clip, and it begins to focus on the life of her son, Dirk. He wants to design buildings, and he works for some years at an architectural firm in Chicago, but he’s in love with a rich girl—the daughter of the school-friend who helped his mom—and she gets him a job selling bonds. He becomes really rich, and he begins an affair with the rich girl (who is married).

Selina, his mother, disapproves of how he’s acting. She asks him point-blank:

“Dirk, are you ever going back to architecture? The war is history. It’s now or never with you. Pretty soon it will be too late. Are you ever going back to architecture? To your profession?”

A clean amputation. “No, Mother.”

She gave an actual gasp, as though icy water had been thrown full in her face. She looked suddenly old, tired. Her shoulders sagged. He stood in the doorway, braced for her reproaches. But when she spoke it was to reproach herself. “Then I’m a failure.”

She had wanted him to lead a good, honorable life. The kind of life that combined ambition, self-expression, and some kind of financial success. The kind of life that she herself, after all her trouble, had managed to lead.

We, the readers, can see that there is a kind of grandeur to Dirk’s mom. That her marriage to his dad was ultimately good. And that she built something strong, in this farm. And she touched many lives for the better. There is a goodness to her that is missing from her son.

The Edna Ferber formula

Most of Ferber’s novels are less accomplished than So Big, because most of them feel structurally a bit lax. Like in Show Boat, a novel about a carnival that’s on a Mississippi riverboart, the core of the story is these two mismatched couples: Parthenia and Andy Hawks, and Gaylord and Kim Ravenal. But getting these couples in the same place at the same time requires a lot of maneuvering and set-up that exhausts some of the energy of the book.

In her novels, you usually have these men—Andy Hawks and Gaylord Ravenal in Show Boat, or the dimwit farmer in So Big, or Clint Maroon in Saratoga Trunk, or Jordan Bennett in Giant, and these men have very strong ideas about how the world works. And those ideas are usually somewhat-incorrect. Like, Gaylord Ravenal thinks he can make money gambling. Andy Hawks thinks just because he owns this boat, he’s really in charge. Clint Maroon thinks that because he’s got a gun, he’s tough; Jordan Bennett thinks because he has a sense of history, and a sense of his ranch’s place in the world, that time will stand still for him.

And then you’ve got these women who have different ideas. Often the women start out with some traditional notions. Parthenia Hawks believes in eastern respectability and domesticity. Kim Ravenal believes in letting her man have his way. Selina DeJong believes she ought to say yes to life, say yes to adventure. Clio Dulane believes she ought to marry for money; Leslie Benedict is intoxicated by the bigness and grandeur of Texas.

But when these notions come into contact with reality, the women are usually able to bend somewhat, in a way that allows them to retain their essential character and come out on top.

It’s very hard to describe the nature of the alterations that occur in these women, because this is exactly where Edna Ferber’s art lies. It’s in precisely the way that she allows each of these woman characters to change and to compromise, without completely losing their integrity.

That balance between integrity and realism—between your principles and your aspirations—is at the core of middle-class life. Edna Ferber knew it was possible to make a lot of money in ways that were dirty, but she also knew that it was possible to make money honestly. And she knew that in both cases, you eventually needed to lose some of your illusions.

But you need to retain some of them too. You can't lose them entirely, because then you end up like Selina’s son, who don’t believe in anything–who think there’s no difference between different kinds of work, different kinds of behavior.

In Edna Ferber’s case, she made her money honestly. These are good books. They have true art in them. However, most of them could’ve used a little more craft—So Big starts off strong right away, with a heroine who’s in peril and has a strong central conflict, but many of these other novels toodle around for a hundred pages, getting the hero and heroine together and establishing their conflict, in a way that ultimately dissipates a lot of the energy of the book.

Okay but should I read So Big?

It’s definitely worth a try! This book is very different book from most other novels that I’ve read from this period. It’s very distinct from even the work of Sinclair Lewis, much less Fitzgerald. So Big is so much less cynical, so much more hopeful.

In searching for more information about Edna Ferber I came across a book called What America Read. The author, Gordon Hutner, argues that the dominant category of fiction in America from the 1920s to the 1960s was something called “Middle-Class Realism”, and that this genre is wholly unrepresented in our mental map of American literature.

Hutner says that the tendency, even in the academy, is to conceive of this period as a battle between modernism (Faulkner) and social realism (Steinbeck), and that modernism somehow ‘won’, but actually both these strands were much less popular than Middle-Class Realism, which was the genre that tended to dominate awards and bestseller lists at this time. In comparison to middle-class realism, even westerns and crime fiction were also relatively marginal genres.

What’s striking, to me, about Middle-Class Realism is that it doesn’t feel like failed modernism or failed social realism. Instead, it seems systematically different, in aim and style and worldview, from the fiction of that era that has tended to survive.

Look at Edna Ferber. Look at So Big. This novel came out the year before The Great Gatsby, and it treats very similar themes: it’s in part about a guy who is lured into the fast life by a rich girl.

But…in Ferber’s work the moral vision is completely different. She does not think America is poisoned—she just thinks this one guy, Dirk DeJong, made some terrible choices. Because in Edna Ferber’s work, someone really can work hard and succeed and be proud of the life they’ve led.

And that carries through to the style too. Everything about the way these books are written is simple and unpretentious. There’s neither an overt message nor any complex imagery. There is a lot of attention to the details of things, especially the details of occupation and business. The book trusts that the drama will flow organically from its depiction of a thoughtful person attempting to make a living under difficult circumstances.

Even to this day, there’s a section of the reading public that is hungry for these books that have middle-class values. Those are books they don’t get from the highbrow establishment, but which they do get from various authors that contemporary critics consider to be subliterary.

In modern times, a great example would be Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow. This is a vastly-popular book about two game designers who actually experience some fulfillment through artistic creation within the capitalist system. It is difficult, and there is struggle, but they are not ruined by this process. Just like Edna Ferber’s characters, the characters in Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow struggle to retain their integrity, but they do manage in the end to lead lives that they can be proud of.

With Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, the problem is the same as with the later Ferber novels—the book is baggy and feels repetitive. The author could’ve pushed themselves harder to get all the pieces into place and tell the most concise version of this story.

This does seem to be a problem with lots of middlebrow books. James Michener suffered the same problem. The books became so long. But highbrow authors can also get very self-indulgent, especially after they succeed, and their self-indulgence is a lot harder to read.

I think that’s why with middlebrow writers, their first breakout is usually the best. For instance, Fredrik Backman’s A Man Called Ove—a book about a crotchety old guy who becomes his immigrant neighbor’s protector—this book is so well-structured. Everything really works. Same thing with Ferber’s breakout, So Big.

When these writers are good, they also have a tendency to turn their goodness into a formula. That’s why I kept reading so many of these Ferber books even though none was as good as So Big! I just enjoyed the regional color—each book is set in a different part of America—and the hilariously mis-matched couples, even as I was frustrated by the increasingly-worse structural issues.

I cannot quite rehabilitate Ferber

With some of the previous bestsellers I’ve written about (The Last of the Mohicans and Uncle Tom’s Cabin), I genuinely felt like people should go and read them, and that they were underrated. With Edna Ferber, the problem is that Willa Cather does exist, and she treats similar themes of middle-class aspiration and contains a similar mix of realism and idealism. To some extent, the existence of Willa Cather would seem to militate against my claim that “Middle-class Realism” never made it into the canon. I would say…Cather is an exception, but a great one.

It’s been a long time since I read Willa Cather, but I went through a phrase where I read a number of her books. I loved her most famous books—My Antonia and Oh Pioneers—but I also really enjoyed her more minor works, especially A Lost Lady (about a railroad tycoon’s very-sad wife). Critics have decided that Willa Cather is unambiguously superior to Ferber, and I’m willing to accept that this is a correct judgement.

Anne Trubek has a great round-up of Cather’s career in this two-part series:

The works for which she is known today were not the ones that made her significant money during her lifetime, and the ones which did throw off huge royalties are no longer known or much read, nor were they critically acclaimed when initially published. There are broadly two Cathers: the one who wrote O Pioneers! And My Antonia, for which she is known, read, and written about today but did not make her famous or rich, and the Cather of One of Ours and Sapphira and the Slave Girl, which are largely forgotten, but providede her with money, awards, and notoriety.

It is possible to have a meaningful life under capitalism

Nonetheless, So Big was quite enjoyable, and I’ve been feeling somewhat inspired by it. This book deeply connected with audiences a hundred years ago, just as it connected with me. It’s easy to classify this book as an example of “Middle-class Realism”, but I don’t know much about the other books in this genre, and it’s hard to believe that there were a lot of books that were as good as this one. This book is the perfect mix of realism and romanticism. It’s about a person’s singular, indomitable will to make a life for herself, but…she does it by growing cabbage.

This was not a sort of book that people had read before. Edna Ferber and her publisher were both surprised that such a slow, quiet book managed to achieve such success. But that’s because the book really felt fresh and different.

And it still feels very fresh now. There is something quite appealing about the values espoused by Selina DeJong. It’s very hard to have integrity under our current political and economic system, but I do think it’s possible, and I don’t think integrity and success are mutually exclusive. It does require luck—Selina freely admits she would’ve gone bankrupt without a loan from her friend. But so what? She deserves that luck, in a way that her son Dirk is never quite able to deserve the much greater fortune he receives.

One cannot read the canon without noticing the tendency in many canonical novels to be highly critical of bourgeois life: it’s a major theme in Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, Catcher In The Rye, Huckleberry Finn, The Great Gatsby, Custom of the Country, Fathers and Sons, “Bartleby the Scrivener”, and many other works.

Whereas what seems relatively rare, at least amongst canonical novels, is to read books that feel any sense of hope and optimism about the possibility that middle-class people can lead honorable lives.

In contrast, when I read So Big, I feel like I am reading about characters who approach life with the same sense of hope and expectation that I do, and I am reading about a world where it is possible for human beings to succeed, within our capitalist system, in leading some kind of meaningful life.

That doesn’t mean these other highbrow books are bad, but to me it does mean that So Big is quite good.

Samuel Richardson Prize

Entries have been flowing in for my prize for best self-published literary novel. Just as a quick reminder, the deadline is July 31st to enter. There is no entry free and no cash prize. All that happens is that your book gets considered by one of our judges, and hopefully it gets reviewed and discussed by a few members of our panel. Full details here.

Some Links

As a reminder, I have a standing offer that if you review a book I’ve written about in the last two months, then I’m happy to post a link to it here.

Zach Dundas wrote a post about the psycho-geography of Raymond Carver, and how he’s rooted in a particular place: Northern California and the Pacific Northwest. This is true, I also get that feeling from his work, although I will note that because of the minimal style there are usually very few overt markers that the stories take place in a particular region, state, geography, or urban/suburban locale.

He was born in Clatskanie, Oregon. He died in Port Angeles, Washington. Both are coastal logging towns wedded to the Northwest woods, places where to this day you can feel the rainy grit and gray-sky mood of a throwback Northwest. They were places, post-New Deal, where working people could make a go of it, but of course those people remained vulnerable to errors of judgement, personal pathologies and romantic trials. There are probably a hundred comparable towns in the Far Corner.

Michael Patrick Brady reminded me of his review of the breakout literary novel of this year, Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection. I think Brady’s review captures the ambiguity of this book, and his preferred reading of it is also my own.

In this reading of the story, Anna and Tom’s ability to put all that angst aside and make peace with their talents as conjurers of the spectacle isn’t a tragedy at all, but a triumph. They’ve realized that their guilt-ridden pursuit of some deeper, more meaningful purpose is futile. There is no greater meaning. Contentment can be an end unto itself. In this reading, one must imagine Anna and Tom happy.

Happy to post more, so please hit me up if you write about Edna Ferber, O. Henry, Maya Martinez, Raymond Carver, Matthew Specktor The Golden Hour or Matthew Gasda’s The Sleepers.

I got this story from Louis Menand’s 2011 review in The New Yorker of the MacDonald essay collection. By the way, now that I know the kinds of short stories the Post usually published (they published many Ferber stories, for instance) it is insane to imagine MacDonald’s essay ever appearing there, because it is basically an attack on the Post’s readers and the kinds of fiction they enjoy.

I should note that Ferber was Jewish—she’s the earliest Jewish-American writer I've read—but none of the four novels of hers that I’ve read are about recognizably Jewish characters.

I still have a lot of thinking (and hopefully writing) to do about what I think about middlebrow. But the first writer I thought of when you were talking about Ferber was Willa Cather (who is one of my favorite American writers.) And I believe that Cather was, for a time, dismissed as, essentially, middlebrow. (Though the term often used was "regional", which is fair in a sense but was, I think, used rather condescendingly in Cather's case.) All that changed after a while, and Cather's reputation became rehabilitated. (I read Anne Trubek's pieces, which I enjoyed very much, but I think she slightly overstated things in suggested that only her weaker novels, like One of Ours (her Pulitzer winner) and Sapphira and the Slave Girl, received attention in her time. One of her best novels was, I think, also very well-received back then: Death Comes for the Archbishop. (Her lovely novella A Lost Lady deserves more attention, too.))

You make a very good point about some middlebrow writers descending into formula. (Frederik Backman is perhaps my wife's favorite writer, by the way.)

I wonder if the center of "middlebrow" in the early 21st Century could be called "Oprah fiction" -- the books Oprah Winfrey chose for her book club. (That being why Franzen got so mad when she picked him!) And some of those books are very good.

There is a list of once very popular and critically acclaimed writers from the '20s through the '60s who are now perhaps called (disparagingly) middlebrow -- Cozzens. O'Hara. Maybe even Dos Passos, though I see James McLoughlin in the Republic of Letters is trying to rehabilitate him!

It’s funny that MacDonald was influential through that reprint. I remember reading that essay and thinking that it certainly got at the middlebrow culture and aspirations of, say, my dad, who believed in literature and being cultured and loved Faulkner (he grew up in the south) but mostlu read books that were solidly in that populist aspirational realistic mode. He loved Peter Taylor who is a better than middlebrow writer but who wrote about the middlebrow; and that it was really just the Frankfurt School of Adorno and company in its scathing and very performative elitism (did you know Auden liked to read detective novels? So much class and other distinctions that don’t matter). Ultimately what I see in stack is that the Substack Boyz and their enablers are basically middlebrow tastes, wanting realism and Art and cultural sanction that fundamentally came from the middlebrow culture existing. Because the secret is that middlebrow readers didn’t ONLY read middlebrow books, at least not all of them. It was an aspiration to cultured refinement. Enough critical attention to a Faulkner or a Mailer or a Yates or a Cheever (three writers who I think were borderliners) and middlebrows would try them. They would pay attention to the critics but also feel a bit huffy that the critics didn’t like Wouk or Michener much.

A lot of writers derided by Substack Boyz litcultism basically ARE middlebrow, like Rooney or Zavin (someday we are going to fight about Kushner, whose Flamethrowers and Mars Room are two of the best books of the last 25 years) at the same time the authors they flog as great are ALSO middlebrow…middlebrow could have plenty of sex and be surface anti-bourgeois too. Lots of writers didn’t know they weren’t reaching the heights.

Bret Easton Ellis and Donna Tartt are two examples of the latter, writers who think they are literature and are really missing the mark.

It’s all a kind of tribal signaling and it can be useful when trying to define or analyze, but always has to be remembered as contingent and unreliable