A creative-writing degree can be quite useful

For as long as I’ve been online, I’ve heard writers asking, "Should I get a Master of the Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing?"

Generally the responses to this question aren't particularly helpful. They're something like, "The degree won't magically turn you into a great writer, but it gives you time to work on your craft."

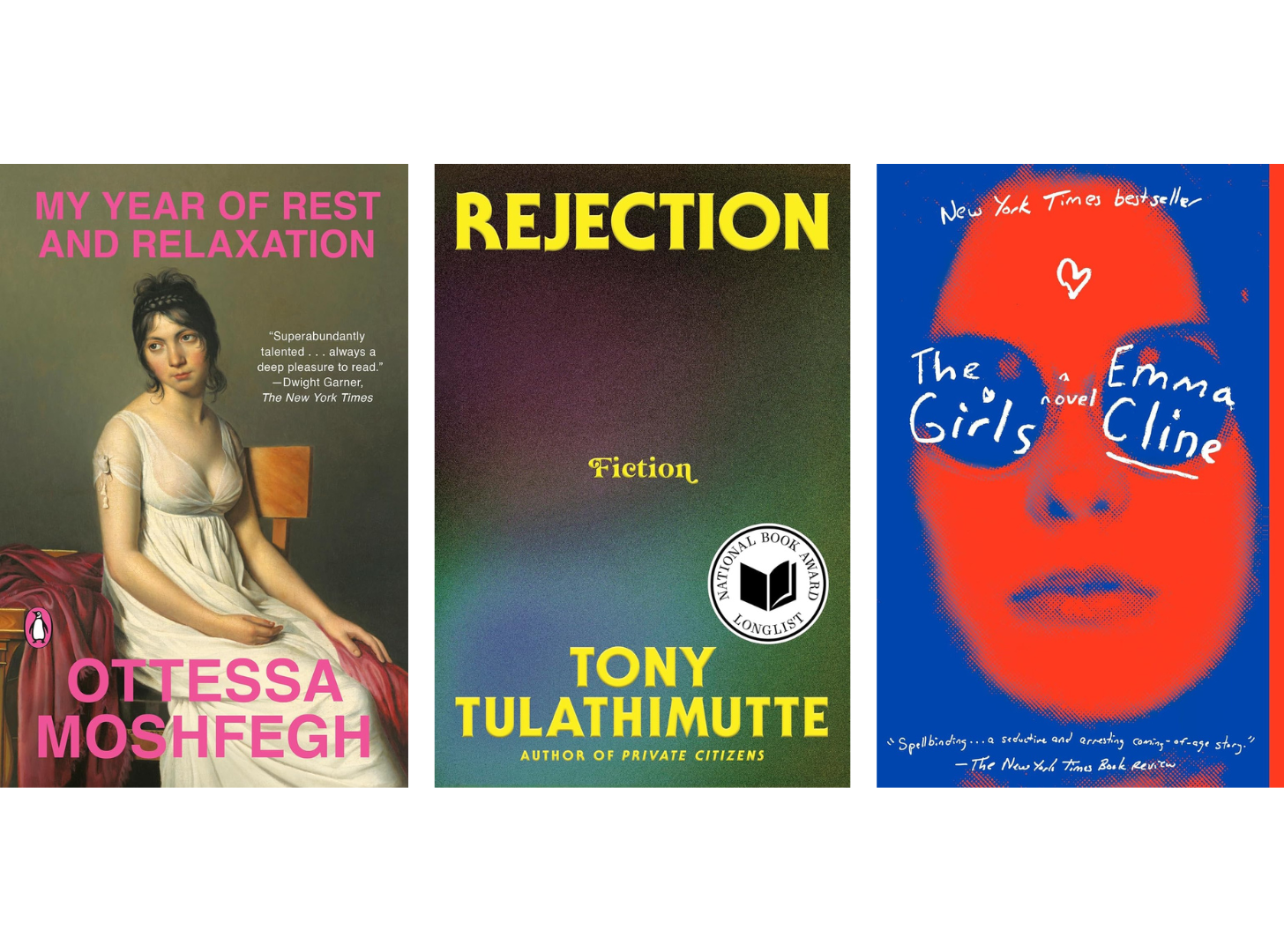

However, this answer seems to ignore the real reason people ask this question. It’s because for the past twenty or so years, many of America's highest-profile literary fiction writers have had MFAs: Junot Diaz, Brandon Taylor, Raven Leilani, Kiley Reid, Tony Tulathimutte, Ottessa Moshfegh, Garth Greenwell, Emma Cline—they all have this degree.

Not every high-profile Anglophone literary writer has an MFA. Elif Batuman does not have one, for instance, nor do most British, Canadian and Irish writers. People who don't have the degree often wear that badge proudly. They claim for themselves some kind of authenticity that comes from not having gone through a writing program.

But aspiring writers still want to know: will doing an MFA help me in achieving success as a writer of literary fiction?

Typically there is a lot of scoffing at this point, and then the discourse about the MFA often spins off into an argument about whether the degree has a homogenizing effect: many would claim that graduate school ruins writers, by forcing them to write lyrical realism or affectless autofiction or whatever other trend people think is destroying literature.

When it comes to the highbrow writing world, there’s a tendency for questions about career and about art to get mixed together. Ultimately everyone wants the same thing: to produce work that is so powerful and singular that the culture bows at your feet and…err…showers you with commercial and critical success.

And we perceive that there is a path to this. For instance, I like the work of Torrey Peters. She got published by a major press, Random House, and she's been nominated for awards and sold plenty of books. So obviously it's possible to be both good and successful. Even if you don't like Torrey Peters, you can probably think of at least one writer who achieved success by writing work that's actually good.

Furthermore, when we look at the careers of these literary stars, we generally see the same pattern behind their success. Typically, before their breakout, they sold a book to a large press and their publisher invested a lot of money into marketing that book.

Now, this isn't a guarantee: many highly-touted books fail to get traction. Moreover, many of these writers weren't necessarily the most highly-anticipated books their publishers released that year. I get the sense that the degree of Torrey Peters' success was a surprise to her publisher, for instance. Nonetheless, she was published by a big press, and there was considerable pre-release excitement for her book. At least for the past ten years, very few literary writers have achieved breakout success without first selling a book to a big publishing house.1

But it’s very difficult to sell a literary novel. In my experience, every stage of a lit-fic career is at least twice as competitive as the comparable stage of a career in the commercial-fiction world. For instance, when I was looking for an agent to represent my second YA novel, I got an offer in a week. A few years later, I was looking for an agent for my debut literary novel, and it took fifteen months and 150 queries. Similarly, my YA novels all sold on their first round of submission. My literary novel took three rounds and forty editors.

I've had several friends who wrote what they considered to be literary novels, but their agents would only submit the books as young adult novels, simply because at that time publishers were much more willing to take a chance on a debut YA novelist (this may no longer be true, because the YA market has flagged).

Thus, I find that when you're trying to sell a literary novel, you need credibility—some sort of external evidence that you're a genius. That’s because literary novels can only succeed if they manage to meet the approval of a gauntlet of intermediaries: critics, booksellers, awards committees, and literary influencers like me. And publishers don't necessarily know what kinds of things those intermediaries will like. So if you come to them with some undeniable credentials—publications in major journals, big residencies, big fellowships—they're more likely to believe you’re capable of getting the attention of literary taste-makers.

This means an aspiring literary writer cannot just develop their voice and write their book—they also need to spend a few years accumulating enough social and/or cultural capital that they can credibly convey the image of being a highly-talented writer.

The MFA is not only a source of credibility in itself, it's also the way you enter the literary world, make yourself legible to it, and learn how to find other sources of credibility.

But to explain exactly how the degree functions, first I need to talk about the four major paths to literary success:

anointing;

grinding;

online popularity;

being part of the New York literary scene.

I don’t think anyone else has described these paths in detail—surely not in the terms I am about to do so—and it’s reasonable to think what I’m saying is a bunch of hogwash. These are just my opinions, based on my observations and the experiences of my friends, and anyone out there is free to disagree if they want.

How I learned about the literary world

During college, I wrote sci-fi stories and submitted them to sci-fi journals. The summer after my sophomore year, in 2006, I attended a six-week writing workshop for sci-fi writers, Clarion (which cost less than $4k). Over the next six years, I sold stories to Nature, Clarkesworld, Apex, Daily Science Fiction, and some other journals that don’t exist anymore.2 I also participated in various online fora associated with the sci-fi writing community.

In my mid-twenties, I decided to attend an MFA program. At that time, Kelly Link was a very popular writer in the sci-fi world and was beginning to have some mainstream attention too, and she had attended an MFA program, at UNC-Greensboro. Another popular sci-fi/fantasy short story writer, Rachel Swirsky, was a graduate of Iowa. So I knew there was some room for science fiction and fantasy in the graduate creative-writing world.

In 2011, I applied to a number of programs, using one science fiction and one realist story as my writing sample, and I accepted an offer of admission to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. This was a two-year fully-funded program. I paid no tuition and received a $22,000 stipend each year.

My aim in attending this program was to learn how to be taken seriously as a writer. I wanted to get a profile in the New York Times where I was photographed wearing a sweater and sitting on the steps of a brownstone. I wanted people to say that I was the first great Millennial novelist. I wanted to have stories in The New Yorker and get a Paris Review interview.

These accolades occasionally accrue to science fiction writers, but they more often come to writers of literary fiction. And, as I’ve written about before, I wanted to write the kind of science fiction that could pass for literary fiction.

During my time at the program, I had two professors who were very squarely in the mainstream of the literary world: Matt Klam was a story-writer who had published six stories in The New Yorker and put out a well-received collection, and Alice McDermott was a novelist who had been shortlisted three times for the Pulitzer.

The program was structured around a weekly workshop. Every semester, each student submitted three stories to be discussed by the class. There was also a readings course, where we read and discussed some set of assigned books. We each also taught an undergraduate section of Introduction to Fiction and Poetry. That was it. That was the program. It was less than 15 hours of work per week.

What I found fascinating about this world is that you can't just ask, "How do I become fancy?" That's because: a) the industry has changed a lot since your professors broke in, so their answers might not work anymore; and b) the rhetoric in these programs is that you're supposed to develop your voice, and, once you're ready, publication will come.

At our program, the professors did not play favorites. I am certain they thought some of us were better writers than others, but that opinion was never obvious.

Our professors were very clearly not in the star-making business: they did not send our stories to Deb at The New Yorker—that was not on the table. Many of my classmates were disappointed by this, but I thought it was the right way to run a program, and I really respected their way of remaining aloof from the students’ career aspirations.

Success through the 'anointing' process

However, in the writing world, there is a distinct anointing process that begins at the MFA. When I was applying, there was a Facebook group for prospective MFA students, and each year there would be a few students who would be the hot-ticket students. They would get into many programs and be able to take their pick.

These same students often went on to place stories in high-profile journals, get agents, and sell books to big publishers.

This anointing phenomenon is something every person who's done an MFA has witnessed: you see some names recur over and over, in fellowship lists, in high-profile journals, and on awards lists.

In my experience, these anointed stars quite frequently fail at the finish line: they publish books that are not particularly well-received by readers, and then their star starts to fade. But I assume that's not always the case: surely some anointed people manage to succeed.

Anyone who enters the MFA world usually wonders, "How do I get anointed? How can I become that person?"

I don't know. Nobody knows. Even the people who've been anointed usually don't know. It's just an impression that they've learned to give off with their writing—the impression that they have great talent. Oftentimes that impression is perceptible from the very first line of their work. They're able to do something that is very attractive to editors and to admissions committees, prize committees, and grants-giving committees of all sorts.

Many people would say that 'something' is their voice. It is their talent. It is their skill.

And perhaps that is indeed the case, I have no idea.

Success through grinding it out

The most successful graduate of my MFA program was Gwen Kirby, who's now a professor at Carleton College. I always thought she was a talented writer, and I often told her so. But I would not say that she was anointed. Everything about her gave off a distinctly scrappy vibe. She submitted her work tenaciously, and she had many more rejections than acceptances. It's not my role to tell her story, but I don't think anyone expected her collection, Shit Cassandra Saw, to have the success it did. This is a book that immediately resonated with readers and moved a lot of copies, at least by literary fiction standards.

Other people who were thought to have much more promise—their work did not achieve nearly the same level of success.

Gwen sold her collection by grinding hard, submitting stories to journals, accumulating a few marquee credits (I think she was published in One Story), getting an agent who was willing to send out her collection, and finding an editor who believed in it. Her agent is Sarah Burnes, who was also the agent of Alice McDermott, one of our professors, but that's not a guarantee—Burnes has turned me down several times and has turned down other people who went to Hopkins.

Gwen was eventually able, through hard work, and working on her stories, to make the literary world believe in her talent. That's the classic model of how the MFA is supposed to work.

Success through online popularity

I, on the other hand, was not able to do that. I had a long path to publication for my novel, The Default World, and when it was released it sank like a stone. Very few people read it. Certainly it got no buzz.

However, in the year after its release I found a following on Substack. As a result of gaining this readership, one of my self-published stories was reviewed by Peter C. Baker in The New Yorker. And after I got that bit of social proof, I found a new agent who is willing to send my short story collection to New York publishing houses. It's unclear whether it'll actually sell or not, but between having New Yorker buzz, a large online following, and a high-profile agent, my odds are much better than they were a year ago.

Getting popular online takes various forms. There was a period of about ten years when it was possible for an article in a literary periodical to go viral and get a lot of attention online. Moreover, these periodicals had a hunger for content, and they were willing to take pitches from anyone, anywhere. During this time, you could develop a fanbase by writing articles that were widely-shared online, and then using those credits to pitch bigger and bigger outlets.

The pieces that went viral were almost never fiction, they were usually essays of some sort, but if you did well enough with these pieces, agents and editors would often be interested in your fiction as well.

During this period, Twitter also became a factor. If you started getting a lot of attention for your online pieces, you could also start tweeting and collect twitter followers. If you became good at tweeting, you could increase your mind-share in the literary community and increase the chances of your pieces being widely read.

It was possible to have this kind of online literary popularity and not live in New York, but most folks who got popular online ended up moving to New York, because online popularity tends to grease the wheels of in-person networking. I speak from experience here: it is much easier to talk to people at literary parties when you know that many of them have already heard of you, and people tend to be much nicer to you when they know you have online clout.

Moreover, in media industries there's a strange phenomenon where you meet people who have a fair amount of influence, but don't have much online clout or even great personal career prospects: in New York, if you're young and popular online, you'll meet assistants, junior editors, book reviewers, and all kinds of other people whose opinion really matters, but who haven't established a name for themselves and who probably won't even be working in the industry in ten years time. If you are well-liked by this younger crowd, it goes a really long way.

Still, it is possible to be popular online and to turn that into a literary career without moving to New York. That is definitely doable. Patricia Lockwood is an example of a writer who did it that way.

Success through living in New York

Then there's a fourth category of people who aren't popular online, but who are popular in New York literary scenes. I am talking old-fashioned popularity: the sort where everyone knows your name, and they are all abuzz talking about you. I'm talking about it-girl status, or whatever the equivalent is for men. I cannot speak to the details of how this works. Maybe somebody can fill us in someday about how you become an it-girl.

Success in the provinces

There is also a form of this game where you get popular in one of the provinces and that somehow translates to social proof that is legible in New York. This is what Torrey Peters did. She belonged to a circle of trans writers based in Seattle, and she self-published several novellas that got buzz among this subculture of trans writers. She does have an MFA from Iowa, but my recollection is that it's in nonfiction, which is a separate program from the famed Iowa Writer’s Workshop, so it's not necessarily a huge source of credibility in the fiction world.

I hesitate to mark this as a genuine path to success, simply because it doesn't seem to have worked for that many writers. New York literary publishing definitely has an eternal thirst for whatever seems underground or indie or authentic, but usually it's able to drink up that authenticity from some wellspring in Lower Manhattan or Queens or the Bronx—it rarely feels the need to look as far afield as Seattle.

What if I'm not anointed, don't live in New York, and I'm not popular online?

When I was in my MFA, a book was released called MFA vs. New York. It was all about whether writers should get an MFA or should move to New York. This book was great because everyone in this volume clearly believed that there wasn't really a third route to success as a literary writer—I found the honesty to be refreshing.

However, we've now established that there is indeed a third route: getting popular online.

But is there another route? Can you be a successful literary writer without being popular online, without entering the MFA world, and without living in New York?

Essentially this is asking: can you have the kind of voice that is immediately compelling to agents and editors, and still get you an agent and a book deal even though you don't have any other traditional markers of the up and coming literary writer (the Iowa degree, the Stegner Fellowship, the Paris Review story, etc)?

Well...I am told that this is possible, but I have my doubts.

If someone didn’t have an MFA, wasn't living in New York, and wasn't popular online or in any in-person literary scene, and they still wanted to write literary fiction, then my sense is their approach would look something like Gwen's. They would have to grind it out. Send their stories to journals and work up to higher-profile publications. There's a tier of journals that is quite accessible through their submissions portal, but which carry cachet in the eyes of agents. If you have had stories in The Kenyon Review, The Missouri Review, Ploughshares, A Public Space, Zyzzyva, American Short Fiction, One Story and about a half-dozen other journals, then agents will probably take notice. There are some fellowships and residencies that are somewhat accessible to people outside the MFA world: Breadloaf, MacDowell, Yaddo, amongst others. These would also carry cachet.

Then, of course, there's the project itself. There is a category of literary novel that still has mass appeal. If your book outwardly resembles the kind of literary novel that is hot these days, then agents might be more excited. For a while, these literary science fiction novels (think Station Eleven) were the rage. Nowadays if you had something similar to All Fours, then maybe people would be more interested—Karin Gillespie describes these dynamics quite well in a recent post.3

Basically, it's a lot easier to sell people something that they know they already want. And it's a lot easier to pitch a kind of book that editors are already looking for. So if your book seems like an easier sell than the typical literary book, agents will probably pay more attention.

But trends move so fast that you just can't bank on them, unfortunately. That's the problem with that I'm describing: it requires a lot of waiting. You're submitting stories for years, hoping to get the credits you'd need to make an agent take your work seriously. Then you need a project—likely a novel—that also feels enticing. It's a lot of waiting and a lot of luck.

Of course, the other routes also involve a lot of luck. Most people I know who did MFAs still couldn’t get publishers interested in their books; most people who moved to New York to become stars didn't make it; and most people who post online don't become popular.

So where does the MFA fit in?

The key to a career as a highbrow writer is credibility. You can't just be good; you need some legible proof, either through credentials or online popularity or indie buzz, that you’re good.

This is quite different from being a writer of commercial fiction. With commercial fiction, the manuscript really does speak for itself. Agents and editors trust their own judgement a lot more when it comes to commercial fiction. They feel confident in their own reaction, and they feel confident that readers will share that reaction.

With commercial fiction, readers are also a lot more willing to take chances. Readers of commercial fiction choose books just by opening the book, looking at the first page, and seeing if they like it. That direct experience of the text is really what sells it.

With literary fiction, the choice of what book to read is mediated by perception. It has to be a brilliant, talented, insightful book. And how do you know if it's brilliant? Because other people say it is.

That means if you're selling yourself to the world as a literary writer, it really helps if you have proof that other people think you're brilliant.

A prestigious MFA is by itself a powerful form of credibility. Furthermore, an MFA also gives you entrance to a world where it's possible to get other forms of credibility. You meet other writers. You observe what they’re doing. And then you start assembling the rest of the ‘talented writer’ package (fellowships, PhD programs, journal publications).

Can't the writing speak for itself?

Look, if you're choosing to write literary fiction, then usually it's because you're aiming to create a kind of aesthetic experience that requires some form of credibility.

My YA novels never succeeded in part because they were pitched to readers as being a certain kind of novel—books that delivered certain simple, reliable pleasures—and my books didn't deliver those pleasures. If they'd instead come to the book thinking, "This is going to deliver some kind of elevated aesthetic experience", then readers probably would've liked them a lot more.

On the other hand, I also stopped writing literary fiction because I realized that I was never going to get the credibility I would need in order to make a literary story work. As a result, I started writing my tales, which don't rely on credibility at all, because they're just simply-told stories about stuff that people already care about.

This is depressing

I'm aware that some people are reading this, and they're feeling kind of hopeless and bad. I would love to be wrong about what I'm saying. I would love if somebody could sit in their study in Gulfport, Mississippi, and spend ten years writing a literary masterpiece and send it out to agents, and then suddenly they're the next Faulkner. That would be fantastic. I hope we live in that world.

But I fear that we do not live in that world, because agents aren't going to want to read that book.

So the person spending ten years in Gulfport should probably do something different. Start a Substack, write for TMR, pitch a piece to George at The New Statesman, then use The New Statesman credit as an entry-point to start pitching widely to all these fancy literary periodicals like The Hedgehog Review and The Point. Start reading the pieces of your peers and sending them appreciative emails. Accumulate a modicum of social proof so that your work might someday be taken seriously.

Or...put together a writing sample and apply for an MFA.

After all, if you do an MFA, maybe you'll get anointed. I think the right MFA really does anchor the anointing process: it’s way easier to believe someone has sui generis talent if they’ve gone down the Iowa MFA to Stegner Fellowship to Breadloaf Fellowship track—if they’ve accumulated all the markers that scream ‘talent’ to a contemporary agent or editor. If you just have the kind of voice that gets you anointed, but you don’t have an anointed CV, then I think the effect of that voice is attenuated.

But even if you're not anointed, an MFA can be somewhat useful in terms of social proof. For someone like Gwen, even though she wasn't anointed, I do think the MFA helped a little bit. It probably cut a few years off her journey, helped her be taken more seriously by editors of literary journals, etc.

However, I know that people have jobs. They have careers. They have families. They can’t take two years off from their lives to do this degree. It’s hard enough to find time to write, but at least you can just do that in the mornings and evenings. Now you’re told that to be taken seriously as a writer you’ve got to do this stupid degree—It’s infuriating.

We are afraid of arousing a sense of anger and hopelessness on the part of aspiring writers of literary fiction. And that’s why nobody ever says, “You need to do an MFA to be taken seriously as a writer.” People instead say, “Of course what matters is the writing.” That’s what they say. But…I don’t think it’s the truth. To make it as a writer of literary fiction, you need more than just good writing.

Have you benefited from your MFA?

The MFA degree gave me exactly what I wanted from it, which was the ability to understand this highbrow literary world that always seemed so opaque. Even now, the highest echelons of the literary world are so shrouded in mystery. In interviews, very few people talk business. Very few talk in an unvarnished way about their journey to publication.

Nowadays I know a lot of literary writers, so I am familiar in many cases with the story of how people got their agents and sold their books, and usually there’s something about it that wouldn’t sound great to an outside reader—often, they’re a friend’s agent, or they’re someone you met at a conference, or they're an agent who reached out because they’d already seen stories of yours.

It’s not that people can’t get agents by a cold-query, it’s just that even if they do, there’s usually something—some credential or connection—that makes agents take notice. And I’m no different. My current agent, Alia Hanna Habib, has a newsletter herself, and I knew she was a subscriber to my own newsletter, so when I got that New Yorker buzz, I reached out to her.

Now…is that a cold email or not? I would say…probably not.

Sometimes I feel a little frustrated trying to describe the difference between the commercial fiction and literary fiction worlds: in the commercial fiction world, people also often get agents through referrals, through meeting agents at conferences, or through other even more off-beat routes. I got my first agent by placing second in the Tu Books New Visions Contest. The winner, Valynne Maetani, was nice enough to introduce me to her agent, John—a guy who’s now a huge powerhouse kidlit agent. This came after a year of fruitless querying where I got very few manuscript requests. I still feel very grateful to Valynne, who was truly exceptional as a connector and a mentor not just to me, but to lots of other people.

So I don’t want to say the commercial fiction world is completely democratic, or that the literary world is totally undemocratic. That’s not true. All I know is that if I meet someone here in San Francisco who is working on a thriller, I am excited for them, because I know it’s possible to get an agent excited about a good thriller. Whereas if they’re working on a literary novel, and they don’t have all these other literary credentials, then I feel afraid, because I worry that even if the book is good, it’ll be very hard to get an agent interested.

What about programs where you pay?

Over the last few decades, four MFA programs have produced the lion's share of the most-acclaimed literary writers in America: Iowa, Michigan, NYU, and Columbia.

Iowa and Michigan are very difficult to get into. If you get in, you should go. They give assistantships to everyone. You get money, you don’t pay money.

At Columbia, virtually everyone pays, and they charge a lot of money, something on the order of 150k for the two-year degree. You can probably get into Columbia. They admit fifty fiction writers per year—it's genuinely not that difficult to get in. My perception is that at Columbia there are stars and there are rubes. The stars often get some form of tuition assistance, while the rubes are paying full freight. Most people at Columbia are rubes.

Nonetheless, Columbia's MFA program does produce a lot of published writers. I think being in New York really helps. To some extent, the program injects you right into the New York literary scene. Some people are rich and are willing to pay 150k for it. Others go into debt. The existence of these stars means nobody in New York publishing can discount someone with a Columbia MFA out of hand, because who knows, maybe they're the next Karen Russell or Emma Cline.

At the same time, the program is simply not that selective! It is in fact shockingly easy to get into. How much credibility can you really get from that? My feeling is that the people in New York know how to smell a rube, and that if you're paying 150k to go to Columbia, it'll count against you, but if anyone wants to argue in favor of the program, I'm willing to listen.

NYU is somewhere in between. When I was applying to schools, some NYU MFA students got tuition assistance and some didn't. Even for those who paid, it cost less than Columbia. I have a close friend who went there, and virtually everyone in her cohort has sold a book. NYU is also a lot more selective than Columbia.

But I dunno. I still wouldn't advise going—I have at least one acquaintance who racked up a lot of debt to attend NYU and dropped out, quit writing because of the financial stress, and said the decision to attend NYU ruined her life. I believe her.

If you’re paying for a full-residency program that’s not NYU or Columbia, I would think twice. Yes they might be cheaper than Columbia, but my sense is that no other pay-to-play program is really producing a lot of successful writers, However if anyone is willing to stick up for one of these programs, please let me know.

The exception is low-residency programs. In the YA world, a lot of people go to the Vermont College of Fine Art’s program for writing children’s fiction. When last I checked, this cost about $40k for a two year program, which seems insanely expensive to me, but I know many people who’ve done it and claim they’ve gotten something out of it. In general, these people are often folks with well-off spouses or white-collar jobs, so $40k doesn’t break their budget, especially because if you do a low-residency program you can still hold down a full-time job. For literary fiction, I don’t know if there’s any low-residency program that I’ve heard amazing things about, but many writers seem to go to Warren Wilson, so maybe they’re okay.

Some state schools also have pay-to-attend MFA programs that aren’t too expensive. Here in SF, we have SF State, which costs about $10k a year. That seems reasonable enough to me. But I wouldn’t do it myself, because what’re they really going to teach you? If you have the money to take off two years to pay for full-time study, you’re better off just moving to New York and trying to get in with literary people. That’ll take you way farther than doing an MFA at SF State.

When it comes to second-tier programs that are fully-funded (i.e. you don’t pay to attend), there are a lot of them that are quite selective, whose name carries a fair amount of cachet, albeit not enough to make anyone truly excited: Austin, Syracuse, Irvine, Hopkins, Cornell, Brown, and a few others. All are fully-funded; they offer tuition waivers and stipends to all their students.

Then there's a number of programs that have less of a name but are still fully-funded: Montana, Virginia Tech, Wyoming. These are also fine. Maybe you'll have a good time, maybe you won't; maybe you'll learn something, maybe you won't.

No MFA is, by itself, enough to make an agent or editor take notice. The trick is to use the prestige of the MFA to acquire the next level of social proof: fellowships, residencies, short story publications, etc. You need to create a web of credentials that tells the story of yourself as a talented person.

But it's all about the writing, right?

Look, I've experienced the literary world and the commercial fiction world, and my experience is that the commercial fiction world is strikingly more democratic, more willing to give a chance to someone without a lot of social or cultural capital. That seems, to me, an undeniable fact.

Literary people really need to reckon with that fact. Their world is not open to outsiders. Of course the writing matters, but clearly it's not the only thing that matters, because if it was the only thing that mattered, then we wouldn't be having this conversation at all, since it would be intuitively obvious, as it is for commercial fiction, that you don't really need credentials in order to sell a book.

If I was forced to guess how people justify this system, I would say that to most literary people, the MFA degree is the field’s attempt at meritocracy. Anyone can get into Iowa. People quite frequently get in who have no credentials, no connections to the literary world. The same is true of other MFA programs. If you’re nobody, the way you get into the literary world is by doing an MFA.

That's how I, a science fiction writer and YA novelist, got the credibility that allows me to make this post—I did an MFA.

I heard if you're a white guy then no amount of credibility is enough

Many people tell me that the industry is biased against white men, and, as I've written before, I am sympathetic to white guys' rabble-rousing. I would much rather white guys put their energy into getting book deals at Scribner instead of doing fascism. I would be fine if non-white people never got another big book deal, so long as it ended fascism.

I genuinely hope the white guys can mint the kinds of literary stars that they want.

But, most of you are not white guys. Most people interested in writing literary fiction are women. Almost everyone at my MFA program was white; lots of them sold books, including one white guy.

Does the MFA homogenize your writing?

This is a question that I don't have a strong opinion about. In my experience, MFA workshops are very receptive to all kinds of different writing. I turned in mostly sci-fi stories to my workshop, and they discussed these stories very respectfully.

The actual instruction in the MFA is not particularly ground-breaking. If you've taken one workshop, you've taken them all. I’ve never spoken to a creative writing professor who was under the illusion that their instruction makes much of a difference one way or another.

Writing fiction isn’t like playing the violin. With the violin, you need instruction because a violin isn’t a natural thing. Nobody can just pick up a violin and start playing. Storytelling is different—it uses our faculty of language, something we’ve all possessed since we were about two years old. The basic techniques of storytelling are familiar to every student long before they enter their first workshop.

Moreover, almost all the instruction on the fiction side is in short story writing, which is silly, because most of the students ultimately want to write novels. Personally, I don't think workshop does much harm. And what we can observe is that Canadian and British writers generally don't do MFAs, and their work doesn't seem that different, stylistically, from what gets put out by American writers.

But, as I said before, I don't have strong opinions about this question. If someone wants to say that MFA programs have some systematic influence on the content of fiction, I suppose that's a reasonable enough assertion. It’s also undeniable that a certain culture can arise within a given MFA program. My own alma mater, Johns Hopkins, is strongly associated with formalist poetry. If you wrote in meter, the poetry faculty loved you. Obviously, that has an impact on what people write.

But I think what has a much bigger effect on writers is this culture of anointing. From the moment you enter the MFA world, you observe that some people are stars and some aren't. And oftentimes it doesn't feel like the stars are necessarily working that much harder, or even writing that much better, than everyone else. This carries the implicit message that you ought to trust authority. When you're ready, you'll be marked out as a star, and there's no hurrying things up.

This means there's a tendency for MFA-educated writers to sit around waiting to be picked. What always stood out to me about Gwen, even back in the MFA, was that she was very tenacious: a quality I highly respected. She sent out her stories assiduously, and she kept working. She didn't let rejection get her down. In this she was quite different from most people I’ve met in the MFA world.

It does feel like the MFA often teaches people to take 'No' for an answer. In part, this is because MFA students quite frequently come from undergrad writing programs where they were overly-encouraged and told that they were great writers. But when they perceive that in the MFA world they are not stars, they often wonder, "What am I doing wrong?" They have no resilience, no ability to weather rejection.

The culture in the sci-fi and YA worlds is quite different. In those worlds, everyone understands that you're nobody until you're somebody. The expectation is that you get lots of rejection and very little encouragement, until you finally sell a book. I think that's a much better lesson for an aspiring writer to learn, and I'm glad that I imbibed those lessons during my most formative years as a writer. It's because of that resilience that I was able to shake off the failure of my literary novel and switch successfully to writing in another form, and it's because of those lessons that, after this Substack fails (as it someday will), I'll pivot to writing thrillers or fantasy novels or nonfiction books or something else entirely.

That kind of inexhaustible life, this inexhaustible belief in your own voice—it's the most important thing a writer can have, and it's something that the MFA tends to destroy—but that's an essay for another day.

Does any of this even matter? I thought literary fiction was dead?

Well, that's the trick, right? Yes, the kind of literary stars we saw ten years ago aren't being minted anymore. But prestige still means something. I myself got a huge boost in subscribers from being mentioned by The New Yorker. That boost added several thousand dollars a year (in paid subscribers) to my bottom line. Being a writer in 2025 means being nimble and building some kind of direct connection to the reader. And readers still care about prestige.

If you were in the Iowa MFA and wrote about it for Substack, you would probably get a lot of attention. Yes, Lan Samantha Chang (the program director) might be mad at you, but so what? She's not going to kick you out. It's the same with all these other institutions. They no longer have the ability to sell you directly to readers, but if you gain their approval then you can still find ways to turn that imprimatur into various forms of social capital that you can hopefully turn into economic and cultural capital later on down the line.

Discourse Credits

This post was inspired by a round of MFA discussion on Substack’s Notes feature a few weeks back. I believe the discourse was started Neo-Passéism in this note. Lincoln Michel responded here.

This interview by Brandon Taylor came out around the same time, and it also touches a bit on MFAs. What Taylor notes in this interview is that even though he went to Iowa, he was not an anointed writer: he was a writer who got popular online:

…I think people have the wrong idea about my path. When I applied to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I had already written several really viral essays. I was an editor for a literary magazine (Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading) and I’d published like a dozen stories or something like that. I was on my second agent before I even printed out those stories and mailed them in.

Prior to about 2014, it was much more common for small-press books to break out and achieve considerable critical and commercial success. For instance, Ben Lerner’s first novel, Leaving Atocha Station, came out from Coffee House Press. Alexander Chee’s first novel, Edinburgh, came out from a tiny press that went bankrupt six months after releasing the book. But in the last ten years, stories like this have become increasingly rare.

I appear in these journals to this day! In fact, I have a story appearing in two days in Lightspeed.

That same post contains a very succinct description of the marketplace for literary fiction:

A study of deals categorized as literary reveals that the authors almost always have either an MFA or PhD, possess an impressive publication record of short stories, and typically work in academia. In other worlds, literary fiction is not just a category, it’s a culture. Publishers still support that culture with imprints devoted to literary fiction but the expectations to entry are high.

If an author writes in a literary style but doesn’t possess the expected credentials, the deal is typically classified as general fiction or upmarket.

I highly recommend Karin’s Pitch Your Novel newsletter. The conceit is that every two months she analyzes the published deal reports—the list of books acquired by publishers during that period—and tries to find some sort of trends. It’s an imperfect system, because publishers don’t report every deal, and you don’t always know the full story behind how the deal got done, but it’s still a fascinating glimpse at the industry.

Thank you, Naomi. As an aspiring novelist almost finished with the second draft of my first (literary) novel, I found this extraordinarily depressing. I’m 33, have a family, have no MFA or intentions of getting one, and genuinely believe (in a non-market-driven, mostly aesthetic, but also selfish sense) that “the writing is all that matters.” I’ve had stories published in journals no one reads or has ever heard of. I do not have an agent and have no clue how to go about snagging one. And yet I continue to write, and I have no plan to stop. I guess my hope is that my novel will find an indie press with decent design and distribution, but who knows? Anyway, thanks for making be feel bad.

I admire your almost computer-like analytical skills and bone-dry way of dealing with uncomfortable facts. Keep up the good work.

This was a joy to read from start to finish.