Random House offered me a deal

Last week, I accepted an offer from Random House to publish my debut story collection: The Payoff includes my self-published novella, “Money Matters”, three other novellas that are original to the collection, and eight shorter pieces (including some that originally appeared in this newsletter).

The deal blurb describes The Payoff as “a story collection centered on money and what you do when you don’t have enough of it, following a cast of linked characters as they steal, gamble, inherit, and wed.”

I am still a bit shocked by this outcome. Large presses like Random House don’t publish very many stand-alone short story collections. In fact, it’s so uncommon that there’s remarkably little information online about how these story-collection deals actually happen. (Former agent Nathan Bransford told authors there was no point querying agents with a collection. He wrote: “If you’ve achieved enough literary success to get a short story collection traditionally published, the agents will come to you.”)

When I began my career, I used to haunt the blogs and forums to figure out the details of how various authors got their book deals. My first books were young adult novels, and in the YA world there’s a culture of transparency: authors are remarkably open about the details of their publication journey. But the literary fiction world tends to be more reticent, which gives the impression that these deals don’t happen unless you’re one of the few, one of the elect.

Last summer, I tried to describe the various paths to selling a work of literary fiction to a big press. And here’s how I summarized things:

I find that when you're trying to sell a literary novel, you need credibility—some sort of external evidence that you're a genius. That’s because literary novels can only succeed if they manage to meet the approval of a gauntlet of intermediaries: critics, booksellers, awards committees, and literary influencers like me. And publishers don't necessarily know what kinds of things those intermediaries will like. So if you come to them with some undeniable credentials—publications in major journals, big residencies, big fellowships—they're more likely to believe you’re capable of getting the attention of literary taste-makers.

When I wrote this post, I hadn’t yet gotten this kind of book deal, so I was only operating on supposition and guesswork. But now that it’s happened for me, I can at least describe my own path.

Breaking into literary fiction

My first YA novel, Enter Title Here, was the subject of a bidding war in 2014 between three publishers. But my next two YA novels each sold for successively smaller advances. However, that was no problem, because I had always really wanted to write literary novels for adults.

I spent several years writing a novel for adults, but when I sent it to my agent in 2020, he said that he didn’t care for it and couldn’t sell it. So I decided to find another agent. But whereas I usually didn’t have difficulty getting representation for my YA projects, I struggled to find an agent who would be willing to send this literary novel to publishers. During that year, I queried about 150 agents.

The project pitched very well, so there was a lot of interest. I got about fifty or sixty manuscript requests. But the novel itself wasn’t connecting with agents. I’d written it in a much-more-distant point of view, somewhat reminiscent of a 19th-century novel, and agents felt they didn’t connect with the protagonist.

So I did several complete rewrites on the book, tightening the point of view each time, and turning it into a much more immediate, but much more conventional, literary novel. I found an agent who was interested in sending it to publishers, but the final version of the book had trouble distinguishing itself from a flood of other queer-themed projects that were also on submission in the same season. Eventually it was picked up by a small nonprofit publisher, Feminist Press. I was happy that the book sold, since it gave me something to show for my years of work. But I felt somewhat burned by the process of pitching my adult-market work to agents and editors.

You don’t want to be ungrateful—after all, no publisher is required to take your work. But the cost/benefit didn’t feel right. I’d put in too much work, suffered too much angst, gotten rejected too many times, and I just didn’t want to go through it again. Part of me suspected that I wasn’t a good fit for literary fiction, and I resolved not to write any more literary novels.

So I started writing something else entirely

Around this period (late 2023 and early 2024), I was reading a lot of pre-modern prose fictions: Greek and Roman novels, the Icelandic family sagas, and Boccaccio’s The Decameron. And these fictions were strikingly unconcerned with point of view. You weren’t inside any character’s head, and you didn’t experience the story through their eyes. In fact, there was very little visual description or sense detail. Instead, the stories more closely resembled fables or jokes or histories—they felt very much like a person was sitting next to you at a fire and telling you a story, extemporaneously, without any artistic flourishes.

One day, inspiration struck: I bet that I could write stories in this style.

From March to June of 2024, I accumulated a stockpile of these stories. Unlike an Icelandic saga, my stories paid a little more attention to the character’s thoughts and psychology, but they were still told by a powerful omniscient narrator, who was capable of skipping around in time or even changing the rules on the fly. This narrator was very confident, fully in control of the story, and certain of their aims. This narrator didn’t just ignore the rules of fiction, she wasn’t even aware of those rules.

(This narrator’s worldview was also heavily informed by The Mahabharata, which I was reading at the time. Her stories were animated by the conviction that the world is ordered by justice, and that all people will eventually receive what is owed to them.)

Finding a home

These stories were a real breakthrough—very different from anything I’d written before.

But when I talked to people about this new format, I could sense their suspicion. My Feminist Press editor said, “Well…it’s all about the execution.”

She was right. Talking about your work is no good! You have to put up, have to show people what you can do. That means getting your work published.

I’d been publishing for fifteen years in top-tier science-fiction journals, and some of these new stories had fantastic elements, so they might find a home in those journals. But other stories wouldn’t be a good fit for even the most experimental sci-fi journals. For these stories, the other potential home was a literary journal—some university-supported publication like The Kenyon Review or Ploughshares.

But…I’d been submitting to these litmags for ten years, and I’d never really broken into the most-respected journals. The submissions process for literary journals was also a big barrier. Sci-fi journals tend to respond quickly, in a month or two. But literary journals are different. They’re very tied to the academic calendar. Usually, each fall you submit a single story to twenty places at once, and you hear back sometime in the spring (during the summer most journals are closed to submissions). Somehow I just wasn’t excited about waiting a year, minimum, before anyone could read these stories.

At the same time, I was maintaining a blog, Woman of Letters, that had about 600 subscribers. The blog was mostly devoted to the Great Books, but…the idea occurred to me that maybe I could post some of these stories online.

If I went the litmag submission route then maybe I would publish one story in a year’s time. Whereas if I sent them to my blog, then my stories would find readers immediately.

Let’s say out of my six hundred subscribers only three hundred opened the email, and only fifty of those people read to the end. Well…fifty was better than nobody.

The beginning of the tale

When I started posting fiction online, I didn’t call them “short stories”. Most people don’t want to read short stories even when they’re published in The New Yorker, much less when they’re in some lady’s blog. So I described my stories as ‘tales’, in order to highlight the ways they were different from the stories you’d read in literary journals.

I told myself that I’d give it six months, posting one tale a week, before I gave up.

Almost immediately, I saw great results. An initial tale was reposted to Reddit or somewhere and brought me fifty new subscribers. Another was restacked widely on this platform and brought me another three hundred. The tales still had lower engagement than the nonfiction side of the blog, but they did pretty well.

During those early days, there were some pretty wild experiments: in several tales, the character died and I visited their afterlife; other tales alternated between fiction and criticism, creating a braided-essay feel. I did all kinds of stuff, just to see what I enjoyed and what was working for the readership.

Around this time, I started going to art shows. And I realized that if you’re a visual artist, there’s a similar process of experimentation. At first, you try out many media, many materials. But at some point, you need to focus on a small set of techniques, motifs, themes, and use them to create a body of work that feels more cohesive. Then, when you’re ready, you put on an art show.

This art show is your announcement to the world that you’re doing something special, and they should take notice.

Money Matters

In September of 2024, I was working on a story that began to spiral out of control. I realized it was going to be much longer than any tale I’d written to date.

Normally I wouldn’t pursue this kind of project, because most of my tales were under two thousand words. But with this story I thought, “Here’s an opportunity!”

This piece would show people that the tale format could accommodate longer and more-complex storytelling. It would be my art show: my signal to the world that I was doing something that was worthy of deeper examination.

But because I would be taxing my audience by posting something so long, I decided to make my life easier in other ways.

When you’re posting stories online, you are confronted rapidly with the limits of your audience. It is very apparent when something is working well for your audience and when it isn’t. It’s not only the viewer metrics—likes, comments, and restacks—it’s also the energy that surrounds the publication of a piece. When something is really hitting, you know it.

I had noticed that realist stories about simple, everyday problems tended to work better, and I started to gravitate towards these kinds of stories (I still wrote science-fiction tales, but I would submit those to sci-fi journals instead of posting them).

And when you’re posting a story for your own audience, it’s harder to rationalize away your failures. For years, I’d tried to write these stories about angry losers. And...I could always convince myself that somehow the publishing industry just didn’t get me. But now I realized that these angry losers were really not compelling even for my blog readership (I later wrote a tale about how you can’t write ‘angry loser’ stories).

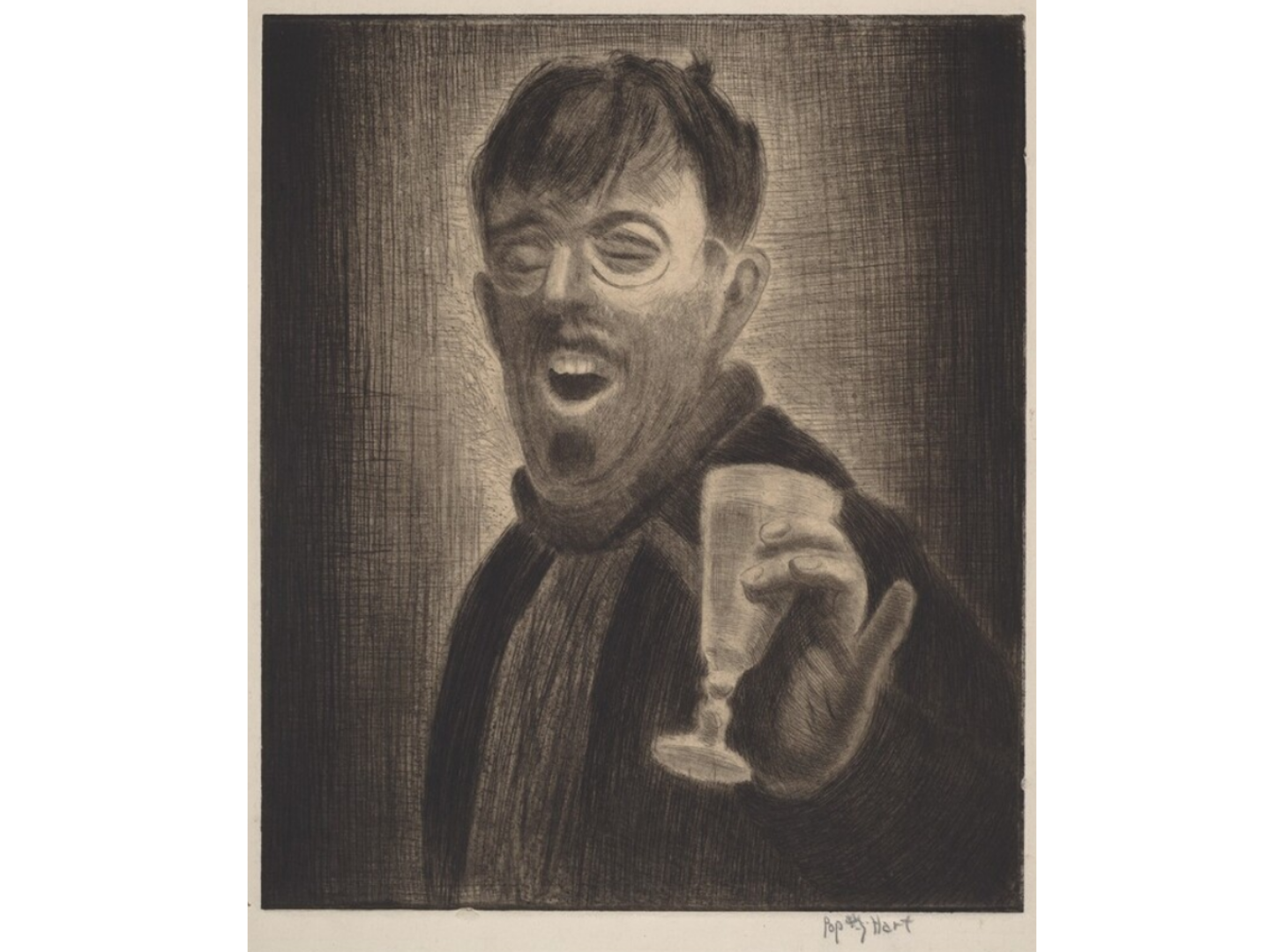

With my novella, I set out to write about the opposite of an angry loser. I wrote about a guy named Jack who was, well, objectively a loser: alcoholic and unemployed. But he had a lot of joie de vivre. This guy approached life with a sardonic amusement that I thought was compelling and aspirational. And he was really good with women (for reasons that he didn’t quite understand).

Jack was faced with a simple problem: he needed to rustle up money for the property taxes on the house in SF that he’d inherited from his uncle. And because he was lazy and shiftless, he concocted a plan to mooch money off his ex-girlfriend, a nurse. But the ex wants him to shape up. Will he pull his life together? Or will he fall apart? Or…will some unexpected third possibility arise?

I gave my audience six weeks of build-up, trying to sell them on the idea of reading this story.

Looking back, I cannot imagine what I thought was going to happen. I guess part of me hoped the story would go viral and take the internet by storm. I’d already had at least one story that broke containment and was shared widely—no reason it couldn’t happen again.

But the novella came out, and it got a good reaction. I had 2200 subscribers, and a sizable subset read the story. Abra McAndrews and Celine Nguyen wrote reviews online, and a few other people praised it, in terms that made me really happy. Then it was over.

The seed of a collection

I wouldn’t say that I felt disappointed. I’d already noticed that my longer and more ambitious tales tended to get fewer likes, less algorithmic traction. And this level of response was actually pretty good. I had also published The Default World that year—a book that was printed up and distributed to bookstores—and the novel hadn’t necessarily gotten more attention than this novella.

But I realized that if I was going to build an audience for my longer fictions, then I’d need a plan. It wasn’t going to just happen on its own, because of a lucky break.

I talked to a few publishing-industry professionals during this period, and they made it clear that no major press would be interested in a collection of self-published stories. I had wondered if my Substack audience—which had grown 5x in less than six months—would make me attractive. But 3,000 subscribers isn’t really that much. The self-pub to trad-pub pipeline is powered by big numbers. If your book is selling tens of thousands of copies, or has a million downloads, then traditional publishers are excited. My three thousand subscribers didn’t really do it.

I shouldn’t overstate the degree of disinterest here. I did feel like, if I tried, I could probably interest a smaller press in my collection. But I was a bit demoralized. Selling a book to a small press is not easy either! With my novel, it’d taken five years of effort to get that Feminist Press deal.

Right now, the tales were fun, but if I started experiencing a lot of rejection, they wouldn’t be fun anymore, and I’d lose the writing activity that brought me the most joy. So although I still wanted to publish a collection someday, I wasn’t actively pursuing that goal in April of 2025.

Instead, my plan was to self-publish a novella every year and enjoy the freedom to write what I wanted.

Substack summer

That year, several of my friends from Substack were releasing small press books. In March, John Pistelli re-launched Major Arcana, which had originally been self-published on Substack and was now coming out from Belt Publishing. And Ross Barkan’s Glass Century came out the following month from Tough Poets.

These books got a lot of coverage from other newsletter writers, which was great. I did interviews with both authors myself.

But then something wild happened. They both got reviewed by Sam Sacks in The Wall Street Journal. This felt new and unexpected. I had published a small press book the previous summer, and it’d gotten no mainstream press coverage of any sort. Meanwhile, Major Arcana and Glass Century kept accumulating press hits and mentions. And it felt like the authors’ popularity on Substack was driving this press coverage (a phenomenon I called ‘Substack summer’).

Then Ross told me that he’d been contacted by a fact-checker from The New Yorker. They asked him some details about the publication of John’s book (Major Arcana had originally come to the attention of Anne Trubek at Belt Publishing because Ross Barkan had read and praised it). The New Yorker was doing an article about fiction writers on Substack!

A week later, on May 11th, 2025, I got a text from Ross Barkan, saying that I was a part of the article.

I quickly googled the piece, and its first sentence was:

This past October, subscribers to Woman of Letters, the Substack newsletter of the writer Naomi Kanakia, received an e-mail titled “Why I am publishing a novella on Substack.”

The article was a roundup of the literary scene on Substack, but it also contained a very positive and generous review of “Money Matters”:

I reached the end in a happily disoriented daze. No other piece of new fiction I read last year gave me a bigger jolt of readerly delight…

The agent search

Immediately, I thought, This changes things. If you have a story published in The New Yorker, you can usually sell a collection to a major publisher. This wasn’t that, but maybe it was close enough.

The article came out on Sunday, May 11th. During the following week, I put together a partial manuscript, containing five stories, and I sent an email to five agents. However, I was still uncertain—the pitch for my collection felt too cerebral, too focused on explaining the nature of the ‘tale’ format. The flexibility and expansiveness of the tale format was at the core of my interest in publishing a book, but I wasn’t sure those ideas would be very compelling to an agent. Perhaps aome other pitch might work better.

From my years of querying, I knew that the same project can often be pitched multiple ways. Moreover, I had so much material that I could probably take the collection in several entirely different directions if I needed to.

Then there was the difficulty of describing my career. I’d done many things, but right now I was mostly known for this Substack that’d grown 10x in the previous year. The absolute number of subscribers wasn’t high, but I needed to figure out how to convey to agents that there was some heat in this Substack. After all, the writer of the New Yorker article, Peter C. Baker, had already been a subscriber to my Substack when I posted the novella. He said in a post of his own that reading my novella was what prompted him to want to write about the Substack fiction ecosystem in the first place.

How could I explain all of this to agents? I knew that it was surprisingly difficult to believably tell someone, “I am popular online”, if that popularity doesn’t come with a really large subscriber-count attached.

But I had a good idea. Several weeks ago, I’d been scanning my subscriber list and seen someone with a gernertco.com email. I knew that Gernert was a high-profile agency, so I googled the email and found the agent’s name, along with this New York magazine article, calling them one of the most powerful New Yorkers I’d never heard of:

When a submission comes in from her, you stop what you’re doing,” says Doubleday senior editor Yaniv Soha of Alia Hanna Habib. The 45-year-old agent possesses the rare ability to start a bidding war just by sending over a manuscript.

This seemed pretty good. Alia was a very high-profile agent who represented many people I’d heard of, like Nikole Hannah-Jones, Clint Smith, Hanif Abdurraqib, Merve Emre, and Lauren Oyler.

She mostly represented nonfiction, so I thought she wouldn’t be interested in a story collection (a form that’s notoriously difficult to sell). However, because she was already familiar with my Substack, I figured she would understand which parts of my story would be most compelling to other agents.

I emailed Alia at 10 AM (Pacific Time). And at 1:30 PM I got an email from her saying she had some ideas, and we should set up a call.

By the next day, she’d read my novella and some of the stories I’d sent (which had all been published on my newsletter), and she had two recommendations:

I shouldn’t try to sell a collection on a partial. Editors would be much more excited if I had a full manuscript. Basically, it’s less risk. I already have fewer credentials than most people selling story collections, so I’m less of a proven quality. At least if I give them a full manuscript, then they know there are no surprises, and they can see exactly what they’re getting.

The manuscript should be more than fifty percent never-published material. I realized later that Alia was using some wisdom here from representing nonfiction clients. Publishers do not want to publish a collection of things you’ve already posted on your blog, because they’re hoping you’ll be able to sell this book to your blog subscribers, and those subscribers won’t be as excited if it’s composed of things they’ve already read before.

These suggestions made sense to me, but I was concerned that maybe now was my moment. The article had just come out, and we should strike while the iron was hot. She said that she would talk to some editors and see if a quick deal was possible, based on just the partial manuscript I’d sent. I mentioned that one good possibility was Caitlin McKenna at Random House. Caitlin had read my novel, The Default World. She hadn’t acquired it, but she gave a very generous pass, and we’d kept in touch a bit after the submission process was over.

During the next week, I did my due diligence on Alia, contacting about twenty of her clients. I love to hear about the worm in the apple. What do people dislike about this agent? And since most people tend to praise their agent, you need to contact a lot of people in order to hear anything bad. However they all had incredible things to say—no red or even yellow flags. I felt good about her and didn’t want to have a beauty contest, so I never nudged any of the other agents I’d queried to tell them I had another offer.

And I came to the conclusion that, even independent of what editors were willing to do, I really wanted to take the time to work on this collection alone, without being weighed down by contractual obligations. I’d successfully written two previous books on contract (my third YA novel and my Princeton University Press book), but I’d also had one very bad experience writing on contract (my first YA book deal was canceled when the editors didn’t like my contractually-obligated follow-up book.) These tales were important to me, and I wanted to get the whole package right and then give them to an editor who really understood my vision.

I signed with Alia and told her I’d go into a cave to work on my book.

The collection gains a theme

Meanwhile, Caitlin was very interested. She read the novella. She subscribed to my Substack, and she suggested that maybe ‘money’ could be a good organizing theme for the collection.

I realized this made perfect sense. I often wrote about money—and I’d even written several well-received essays (in LitHub and The Dirt) about why authors should write more about money. So it was definitely a major preoccupation of mine. And it also gave me some guidance on how to select from my existing oeuvre.

I decided that the collection would consist of four novellas and a few smaller tales. They’d all be realist tales and all set in San Francisco. One would be “Money Matters”, but the other three novellas would be constructed from the raw materials of my various works-in-progress.

For instance, I’d written a set of six Silicon Valley tales, but the combined effect of the six was somewhat fragmentary, so I decided to set them aside and use those themes and situations to write one big story.

Another novella started as a novel (I even had a complete draft of the book!). It wasn’t working in novel form, but I boiled down the story into fifteen thousand words.

And a third novella had been a work-in-progress, slated for publication at the end of the year.

It was actually very good to be able to work with unpublished pieces, and to not be so bound to versions that’d originally appeared on my blog or on my Substack. That meant I could balance the elements, use people from different strata, different parts of the city, different walks of life. When I was done, the stories fit together to form a portrait of middle-class life in San Francisco.

The submission process

At the end of last year I sent a draft to Alia. We did a round of revisions, and then two weeks ago she put it on submission. Because of Caitlin’s interest, we decided to give her a three-day exclusive before it went wide. With an exclusive, you likely get a quick yes or no from that editor, but you lose the chance to shop around their offer and maybe get into a competitive situation where you have lots of publishers outbidding each other.

That seemed fine to me. A short story collection is a hard sell. It would be amazing to get even one offer from a big publisher who was excited about the book.

Anyway, on the morning of the third day, Alia sent me an email with the subject line Call me!!!

I couldn’t right away, because I had to drop my daughter off at school. But once I was back home, Alia told me there was an offer. And she quoted me a number that seemed pretty good. Certainly it was more than I’d been paid for any of my YA novels, and it indicated that Random House was really serious about the book.

Then there were some intervening steps (a call with Caitlin, and some negotiation about the number), but basically that was it!

My collection of tales, The Payoff, is coming out from Random House in late 2027 or early 2028.

Luck played a major role

I probably won’t mention this book too much for a while. It’s got to go through edits, then enter into the production process. There’s not even a preorder link yet. But...thank you all for being with me on this journey.

And I also owe a lot to these three people, Peter C. Baker, Alia Hanna Habib, and Caitlin McKenna. Without their wisdom and experience, this deal could never have happened.

Peter is the one who contributed the most to this. I got very lucky that he was amongst my readers. I’ve since gotten to know him a bit better—from reading his newsletter—and I’ve learned that he’s transitioned to a new career, as an English teacher, and isn’t writing for magazines so much, so I am grateful he didn’t succumb to senioritis and just table the Substack fiction idea.

He’s written a few elegies for the magazine world he left behind, and it’s clear that he had a lot of expertise in how to pitch a story and make it sound attractive to editors. I see now that the way he wrote this story created much more impact than if he’d just said, “I found a good self-published novella”. And I benefited directly from that increased impact.

Secondly, I ran across the right agent. Alia really has a spark of genius. Within a day of my first email, she’d formed a vision of how to sell this collection. She works with many authors who have social media platforms, and she came at this project with an immediate understanding of how to pitch a project as the natural outgrowth of a given platform. You don’t want to say, “This is stuff that’s been published before”, but you do want to say, “There is a proven audience for this work.” It’s a delicate pitch, and she did an incredible job. It’s very, very hard to sell a story collection, and even harder to sell something that feels so new and unproven, but she was excited by the challenge. I feel lucky to have connected with her.

And Caitlin McKenna pursued this project. She subscribed to my newsletter, she kept up her interest. And she provided the idea—that money framing—that was obviously a very natural fit for the kind of thing that I write, but which hadn’t occurred to me on my own.

Without these three, my story would’ve ended up very differently.

And even before them, from the moment I came onto Substack, Daniel Oppenheimer, John Pistelli, Ross Barkan, Sam Kahn, BDM, Timothy Burke, Joshua Doležal, Phil Christman, Virginia Postrel and Henry Oliver were huge supporters. When I started on the platform in 2023, I imported a subscriber list of 200 people, and it was mostly composed of real-life friends and family (plus a few diehard fans from my Wordpress days—shout-out to Julia!). It was on Substack that I really became part of a literary community.

I remember that in 2024 I did a reading in support of my novel, The Default World, at KGB Bar in New York, and Ross Barkan showed up—the first time we met. This was a popular trans-themed reading series, so there were lots of people in attendance, but nobody specifically in my corner—It was really nice of him to come out.

Without that initial readership, I never would’ve kept posting. Remember, I had no idea that a book deal would come out of it. I considered myself retired from publishing books: I was motivated entirely by the desire to connect with other people on the platform. They were my only audience.

I started a Facebook account in 2004, and a Twitter account in 2009. That’s twenty-two years of continuous social media. I can’t say what’s made Substack so much more fruitful for me than any of these other platforms, but it’s undeniably the case that I wouldn’t have a career if it wasn’t for this platform. Somehow, Substack has been a very good fit for my talents and personality, and I’m grateful that it exists.

My angry loser story

After my experiences with The Default World, I built up a worldview where somehow good things could never happen to me. I figured that in the adult literary fiction world, there were anointed stars, and these were the people whose submissions got taken seriously. And people like me weren’t allowed to be ambitious. If we did something that looked weird, then the industry didn’t think, “Maybe there’s something here.” Instead they thought, “You’re writing badly.”

My favorite description of the litfic world came from Karin Gillespie, who wrote:

A study of deals categorized as literary reveals that the authors almost always have either an MFA or PhD, possess an impressive publication record of short stories, and typically work in academia. In other words, literary fiction is not just a category, it’s a culture. Publishers still support that culture with imprints devoted to literary fiction but the expectations to entry are high.

Personally, my experience selling The Payoff has only confirmed my opinion that it’s very, very hard to sell literary fiction, and that if you’re going to do it you really need some secret sauce.

Five years ago, when I was pitching The Default World, I didn’t have that sauce, and the industry was largely uninterested. They pushed me to rewrite the book in more accessible terms.

But maybe my problem was that my voice wasn’t mature yet. Maybe if I’d written with more confidence, I could’ve won them over.

Well, two years ago, I had a massive creative breakthrough that changed my writing completely. I wrote “Money Matters” very shortly after that breakthrough, and I tried a few times to get the industry’s attention with that novella. But it really didn’t seem like there was a lot of interest.

The writing, by itself, was not enough to make literary publishers take notice. Not even my exponentially-increasing online audience was enough, by itself, to sell a book. It really took the New Yorker review to get this industry interested in my short fiction. Without that review I don’t know if any big publisher would’ve truly considered this project, or if any agent would’ve even sent it out.

I’m not saying that my collection doesn’t deserve to be published. I just think…whether I was deserving or not, it would’ve been very difficult to make my accomplishments legible to a prestige publishing house if I hadn’t also gotten this mainstream critical acclaim.

This blog is my highest priority

I want to close by saying…my aim in writing this newsletter was never to get a publishing deal. Nothing I’ve done in my writing career has given me as much joy as Woman of Letters. During the same time period when I was writing three new novellas for my collection, I was also careful to keep up my publishing schedule here. Not only did I deliver two of my most ambitious essays, on the Western and the New Yorker story, but I also experimented with different types of tales, including a pseudobibliography, a series of sword-and-sorcery tales, several first-person narratives, and a few O. Henry-style stories with surprising twist endings.

It’s quite common for content creators to stop prioritizing their online audience once they get their big break. You see this with bloggers who become staff writers, or webcomic artists who switch to writing graphic novels. And I think it’s generally a mistake: these industries are fickle, and they often abandon you after a few years and leave you with nothing. In contrast, there are YouTubers, bloggers, and webcomic artists who’re still going, producing content for their online audience, after fifteen or twenty years. My ambition in life is to be like Randall Munroe—an online creator with occasional book-length projects. I’m still figuring out what works best for online vs. book-length, but Woman of Letters remains my top priority.

After all, my collection could easily fail. I’ve had plenty of books underperform in ways that harmed my career. It’s shocking that I’ve gotten another chance. This is all so new that I’m having difficulty really processing it, incorporating it into my self-image.

Hopefully you’ll forgive me if this post feels a little inchoate: I just wanted to put the facts out there, for the benefit of anyone else who’s lain awake wondering “How in the world did that deal happen?”

Woman of Letters meetup in Baltimore!

AWP is a conference for MFA students and the people who work at MFA programs. This year it is in Baltimore from March 4th to March 8th. Baltimore is the city where I did my MFA, and I have fond memories of the town. Hence, I am attending AWP.

I have gone to this conference eight or nine times, and I’ve always found it to be extremely depressing. Sometimes I have a major depressive episode when I attend, but usually the conference is more tolerable. This time I am hoping for the latter experience.

Anyway, I thought it would be fun to do a Woman of Letters meetup! The meetup will consist of…me. And my vision is that we will likely hang out in a hotel lobby on Thursday, March 5th, at 11 AM. The exact lobby location is still TBD.

Please click this button and fill out the Eventbrite if you want to attend the meetup!

Friday events at AWP

If you can’t commit to the meetup experience, I am also doing two events, both on Friday, March 6th:

A Panel: Ink Under Siege: Writing for Queer & Trans Teens in the Era of Book Bans

This is a classic queer YA diversity panel, of the sort I’ve been on roughly twenty or thirty times. Should be fun enough. It’s at 1:15 PM on Friday in Room 326, Level 300, Baltimore Convention Center

A Signing

I will be signing copies of my novel, The Default World, at the Feminist Press booth in the Bookfair at 2 PM on Friday, March 6th

Links

Last year I wrote a post about Lonesome Dove, and now Matthew Long sent me a link to his own thoughts on the novel. I only read the first two books, but Long gives his thoughts on the whole tetralogy:

Augustus McCrae is one of literature’s great studies in how a man can evolve profoundly while remaining essentially himself. What makes Gus’s journey so compelling across the tetralogy is precisely this tension between transformation and constancy—he changes deeply while somehow never betraying his fundamental nature.

I love linking to other peoples’ takes (positive or negative) about books I’ve also written about recently, so if you have posted recently about A Little Life, The Mind Reels, The Whitney Review of Books, or The Stories of John Cheever, please let me know!

P.S. My daughter has a bizarre school break that takes place in mid-February—a weeklong holiday that is informally known as ‘ski week’. As a result, Woman of Letters will be on hiatus for two weeks. I should be back March 3rd.

hell yeah

Go you!!!! What a journey! I don't know what it is about your success that makes me root for you rather than be insanely jealous of you, but I think it has to do with the sheer amount of labor you have put in, your humbleness about your own not-knowing, and the underlying heartening non-formula formula here for other writers that is something like elbow grease + luck + "Do what you want to do/follow the path that calls to you." Big congrats, and I look forward to The Payoff.