The New Yorker offered him a deal

Two months ago, I read a seven-hundred-page collection of short stories by John Cheever. But somehow that wasn’t enough. I went on to read seven-hundred-page retrospective collections from Mavis Gallant, Alice Adams, and John O’Hara. And I still wanted more!

Normally when I get halfway through a story collection I think, “Okay...I’m done now”, but with these authors, it wasn’t like that. I wanted more. Not more of these particular writers, but more work that was like their work in some weird, indefinable way.

What’s even weirder was that although these authors were different from each other, there was also a lot of similarity. They tended to write in a journalistic style, heavy on description, without a lot of judgment. The writing felt like a clear pane of glass, as if you were just seeing through to the life underneath. Their stories also tended to be light on plot—the characters were quite passive, tossed-around by life, and the stories would end in oblique, understated ways.

A classic example is Alice Adams’s “Beautiful Girl”, about a man who visits an ex-lover who’s become an alcoholic. When she falls asleep, he murmurs something about how he’d love her to come home and be his beautiful girl again. The woman wakes up and shouts, “I am a beautiful girl!”

That’s it. Then the story is over.

I know this sounds boring. I enjoy plot. I enjoy story. I enjoy conflict. I enjoy resolution—I never pictured myself as an avid consumer of these plotless, understated stories.

And yet, I kept reading them. All of these initial four writers (Cheever, Gallant, Adams, and O’Hara) were primarily published in The New Yorker. And I could sense that The New Yorker had shaped their outlook. All my life, I’ve heard about this thing, “the New Yorker story”. I hadn’t investigated this term in depth, but I understood it to mean “a short story that is meandering, plotless, and slight—full of middle-class people discussing their relentlessly banal problems”.

And yes, these stories definitely fit that description. But they were also good!

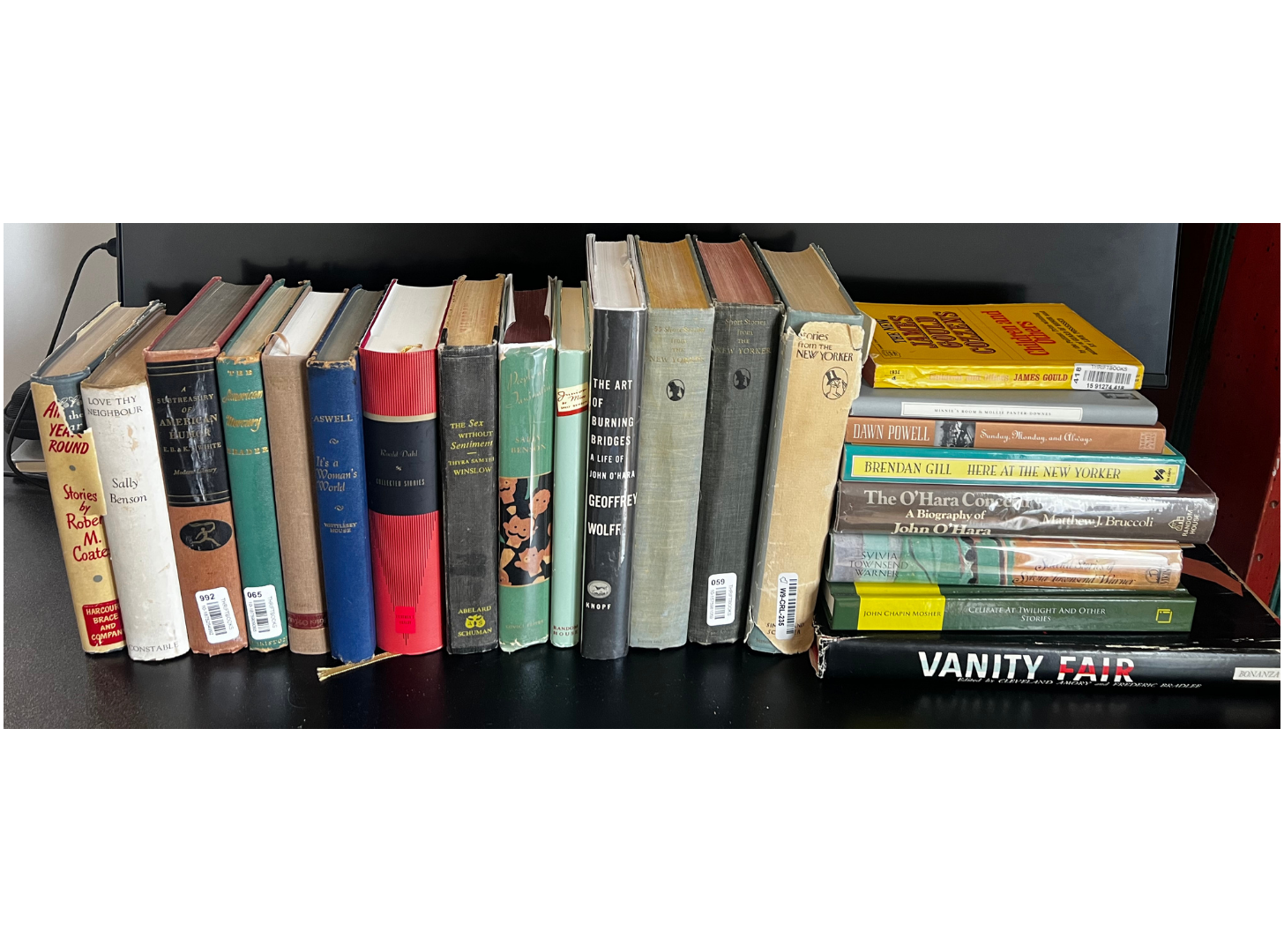

I became very interested in figuring out the essence of the New Yorker story. So I hunted up three early anthologies of New Yorker stories (published in 1940, 1949, and 1960). And whenever I spotted a writer who seemed particularly New Yorker-y, I read more of their work. That’s how I ended up reading complete collections by Sally Benson, Thyra Samter Winslow, Jerome Weidman, Wolcott Gibbs, Nancy Hale, and Dorothy Parker (as well individual stories by dozens of other writers).

All told, I’ve probably read five hundred New Yorker stories over the last three months.

Part of me thought this investigation would amount to nothing. Last summer, I did a similar deep dive into The Saturday Evening Post. I wanted to investigate the quintessential Post story. But I found myself bored by most of those stories, and I lost interest in the project. Similarly, in the fall I read a ton of Louis L’Amour novels to figure out his secret, but I came away somewhat stymied in that investigation as well.

With The New Yorker, it was very different. The more of these stories I read, the more I was impressed with their commonalities, and with the amount of life that thrummed through this form. Although they were tightly constrained in terms of their style and subject matter, there seemed within those bounds to be an endless amount of novelty.

Not only were these stories similar to each other, but they also seemed quite different from other literary stories. These stories were mostly marked by their extreme restraint. They didn’t just eschew plot, they also eschewed lyricism, symbolism, surrealism, or any other devices that would call attention to themselves. Their plotlessness made them seem highbrow, but their unadorned style made them highly accessible. And I wondered how The New Yorker could’ve arrived at this unique-seeming combination of elements.

The New Yorker ‘casual’

When the New Yorker was founded in 1925, it was meant to be a humor magazine. And for its first five years, it didn’t publish much fiction. Instead, it published something called “casuals”—short humorous pieces that were meant to convey an attitude of urbane sophistication.

Many of these casuals consist of little snatches of language (“talk stories”). The conceit is that you’re overhearing something funny. Or sometimes there’d be a brief sketch of a type of person. Or there’d be a short dialogue.

If you’ve ever seen a New Yorker cartoon, you understand this early style of New Yorker humor. It’s not meant to be laugh-out-loud funny. Instead it’s mordant, dry, and slightly obscure. The journal assumes the reader will understand whatever is supposed to be funny.

John O’Hara published an incredibly large number of these casuals—I’d estimate at least seventy-five of his pieces in the journal take this form. And they’re not really stories. For instance, here’s a casual he wrote called “Varsity Manager”.

“He proves, if nothing else does, that nothing in his college career so ages a man as does election to the football managership.”

The sketch continues in this vein. It’s an extended description of the type of guy who gets elected to manage a varsity football team in 1930.

The inventor of the New Yorker story

But around 1929, the second-in-command at the New Yorker, Katherine White, persuaded her boss, Harold Ross, to let her publish some non-humorous short stories.

The managing editor of the paper, Harold Ross, was never totally sold on the idea of publishing stories, and there was constant tussling with him over stories he thought were too arty, too literary. For a story to appear in The New Yorker, White had to think it was good, and Ross had to think it wasn’t too confusing. He was adamant on this last point: his watchword was ‘sophistication’, and the readers wouldn’t feel sophisticated if they couldn’t understand the stories in the magazine.

And Katherine White found an author who perfectly suited the needs of the magazine: Sally Benson.

Benson is the woman who invented the New Yorker story. Not only did she publish 100 stories in the New Yorker between 1929 and 1942, but her style of fiction also seemed to be the prototype for their early fictional output—reviews of the New Yorker’s fiction from this period almost always mention Benson’s work.

Sally Benson was a wife and mother and freelance writer living in New York. At the age of thirty-two she began writing fiction, and she almost immediately sold a story to The New Yorker. For the remainder of the thirties she sold them an average of ten stories a year.

Her stories were almost always very short (under 2000 words), and they were characterized by brevity, plotlessness, a plain style, and a cold outlook. Her endings are particularly notable—often the stories terminate with a moment of action, dialogue or observation that’s allowed to speak for itself. There is no overt judgment, but it’s clear that the character’s failings are being held up to a terrible scrutiny.

For instance, in “Goodbye, Summer”, a bad kid talks a good girl into going out with him on a date. But at the last minute her mother convinces her it’s not a good idea. The bad kid gets into his car and drives recklessly through town. The story ends with the lines:

…and although his eyes were reckless and wild and he told himself he wanted to die, some instinct made him slow down slightly when he reached the sharp turns in the road.

It’s devastating. He’s not really bad. He wants to act out, but even in his most angry moment he can’t really lose control.

In “Retreat”, a woman is stuck in a convalescent home. She convinces herself she’s perfectly happy and having a great time. But after getting a message from her daughter, the woman begins to cry (“Oh, my God,” she sobbed, “I’ve got to get out of here! Oh, my God, I’ve got to get out of here!”) The nature of the home is never explained, but it’s obviously a sanitarium for alcoholics.

In “Men Really Rule The World”, a woman keeps telling her friend about how useless and helpless her husband is. But then there’s an air-raid siren, and her husband bursts in, turns off the lights, and forces them all to sit in the dark (i.e. he’s really in charge).

In all these cases, the meaning of the ending isn’t really spelled out, but only a simpleton wouldn’t get it. That’s what makes the stories so fun! They’re like playing the Wordle: the game feels difficult, but in reality it’s very hard to lose.

A growing cohort

Other writers began to produce work in a very similar style. Short, plainly-written, plotless, with slightly-enigmatic endings.

In Paul Horgan’s “Parochial School”, a nun is very excited that the bishop is coming to visit her classroom. She gets the students all hyped up for the visit. Then he comes, lingers in the doorway for a second, and he’s gone.

In John O’Hara’s “Over the River and Through the Wood”, an elderly man goes to visit his son. The father is sober, there’s an implication he’s done something in the past, lost his money. He gets fixated on one of his granddaughter’s teenage friends, who’s also visiting, and accidentally barges in on the girl while she’s naked:

He knew, it would be hours before he would begin to hate himself. For a while he would just sit there and plan his own terror.

And in John Cheever’s “Summer Theater”, a dance instructor gets mad at the theater’s drama teacher, an aging professional actress. Later everyone sees the diva bobbing in the water, and they assume she’s drowned herself, but really she just went for a swim (“She was too absorbed in her own pleasure to notice how they stared”). You realize this diva is used to ignoring peoples’ insults and jibes.

The genre coalesces

These stories sound like they’re a bit generic. You might ask, “How could so many writers arrive independently at this very particular sketch-like form?”

Well...they didn’t.

The editors of the journal encouraged prospective writers to use this style.

Katherine White stated the case in an early rejection letter: “This matter of fiction for The New Yorker is difficult and since we do not regularly run stories they must be so perfect that we cannot see our way clear not to use them.”

And what was a perfect story? She was emphatic about one thing: The New Yorker didn’t care for stories with a lot of plot. After breaking into The New Yorker, Sally Benson sent two other stories that were rejected, and Katherine wrote back, “We feel that the effect of your other story was in the lack of elaborateness, and the lack of plot.”

White associated highly-plotted stories with standard magazine fiction that appeared in the big periodicals, and she wanted New Yorker stories to feel different, right off the bat, from anything you’d read in Cosmopolitan or The Saturday Evening Post.

At the same time, Katherine White didn’t want stories that were ‘special’ or otherwise inaccessible to the reader. When a story had a more florid, maximalist style, with lots of figurative language, she was prone to calling it ‘dizzy’. And she believed that the New Yorker’s ‘rather straightforward’ audience didn’t want to read ‘dizzy’ stories.

This latter requirement was in part necessitated by the editor, Harold Ross, who absolutely refused to print any story that he couldn’t understand. Ross also hated any discussion of sex or immorality. Even adultery could only be hinted at or alluded to. His magazine couldn’t contain anything that might give bad ideas to a child.

The New Yorker story was defined by three things: the first was Katherine’s determination to print something very different from what you’d see in other journals; the second was Ross’s mandate that all stories be perfectly clear and comprehensible and clean; and the third was the literary ambitions of The New Yorker’s stable of contributors.

The allure of prestige

Katherine White, the fiction editor, was determined to win some respect for this variety of fiction. So she contracted with Simon and Schuster to release an anthology of the best stories from the first fifteen years of The New Yorker. She decided that this anthology wouldn’t contain humorous sketches, just pieces she considered real short stories.

This collection came out, in 1940, to mixed reviews. Almost all reviewers took it as an opportunity to deliver their overall thoughts about fiction in The New Yorker. Most critics agreed that New Yorker fiction was entertaining and unique, but many thought the stories were insubstantial.

The most incisive review of the 1940 collection came from Lionel Trilling, writing for The Nation:

There can be no question about the talent of all these stories or about the brilliance of many of them...but almost all the authors subscribe to the myth of their personal nonexistence or of their merely corporate existence; they are all the same anonymous person, and you feel about them that, just as any scientist might take over another’s research or any priest take over another’s ritual duty, almost any one of these writers might write another’s story in the same cool, remote prose.

He then critiques the anthology’s limited ambitions and lack of style.

By 1940, the New Yorker’s fiction had already gotten a reputation for slight, insubstantial, and concerned primarily with the quotidian problems of middle-class people.

In a review of Sally Benson’s final collection in 1942, a writer for the New York Times said, “But, in the category of fiction [the New Yorker] has run a Marathon with itself to determine how close slightness may approach zero and yet exist.”

II. The New Yorker breaks out

When I first looked at that 1940 collection, I recognized only a few names: Christopher Isherwood, Sherwood Anderson, Dorothy Parker, John O’Hara, Louise Bogan, John Cheever and Erskine Caldwell. But I recognized virtually none of the stories. Even when these writers were famous, they were generally not famous for the kinds of stories they were writing in The New Yorker between 1925 and 1940.

The situation when it comes to the follow-up volume, 55 Short Stories From The New Yorker, was very different. This book, which collects the best New Yorker fiction from 1940 to 1949, contains two of the most famous short stories in American literary history: J.D. Salinger’s “A Perfect Day For Bananafish” and Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”. It also contains a story, “Colette”, that would later become part of Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, and it contains one of Cheever’s best-known stories, “An Enormous Radio”.

(It also contains many more names that I recognize: Mary McCarthy, William Maxwell, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Peter Taylor, Jean Stafford, and Frank O’Connor.)

The 1960 volume, the third and last to be edited by Katherine White, is more distinguished still. I recognized more than half the names: Elizabeth Bishop, Elizabeth Hardwick, Elizabeth Taylor, Eudora Welty, Frank O’Connor, Harold Brodkey, J.D. Salinger, John Cheever, John Updike, Mary McCarthy, Mavis Gallant, Nadine Gordimer, Peter Taylor, Philip Roth, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, Richard Wilbur, Roald Dahl, Saul Bellow, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Tennessee Williams, V.S. Pritchett, Vladimir Nabokov, and William Maxwell.

And although no story in the 1960 volume is quite as famous as “The Lottery”, there are a few that’ve become well-known: John Cheever’s “The Country Husband”, Frank O’Connor’s “Man of the House”, and Harold Brodkey’s “Sentimental Education”.

So what changed between 1940 and 1960?

I would say that two interconnected things happened. The first was that stories in The New Yorker started getting much longer. Harold Ross always used to try to keep them under 2000 words, and in fact he wrote into New Yorker contracts that you’d get paid more per word for the first 1500 words of a story. But writers kept breaking through this length limit, and the fiction editors kept asking him to print longer and longer stories.

It was during WWII that the length limit really started to expand: that’s when Irwin Shaw published the journal’s longest-ever story, “Act of Faith”, at about 6,000 words. Then, in 1949, Peter Taylor had a story that was ten thousand words (a new record for the journal). A few years later, Peter Taylor set a new record with a 14,000 word story. And after that, there was seemingly no limit: before the fifties were over, the New Yorker printed Salinger’s “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” (22,000 words) and “Zooey” (40,000 words).

Second, and more importantly, the editors at the New Yorker started to publish stories that took more risks with form and content.

The break-out year for the New Yorker story was 1948, when it published both “The Lottery” and “A Perfect Day For Bananafish”.

Both of these stories begin like fairly typical New Yorker stories. “The Lottery” is about some quaint small-town ritual. “A Perfect Day For Bananafish” opens with a newlywed bride on the phone with her mom. The bride is complaining that her husband seems a bit odd.

But in both cases, the ending is quite inexplicable. “The Lottery” closes with a woman being stoned to death, while Bananafish closes with Seymour Glass killing himself, seemingly for no reason.

These stories, “The Lottery” and “A Perfect Day For Bananafish”, still feel recognizably like New Yorker stories. They’re told in the same flat, matter-of-fact style. They’re about simple, easy to recognize situations. But they also contain something truly mysterious, something that’s not easy to understand.

Harold Ross, the founding editor of The New Yorker, was in his last years (he would die in 1951), and he sometimes protested against the type of fiction that was increasingly filling the page of the journal he’d originally conceived as a humor weekly.

As James Thurber reports in his memoir, The Years With Ross:

[Ross] was quick to recognize the quality of such fiction writers as Newhouse, Irwin Shaw, J. D. Salinger, Jean Stafford, and John Cheever, to name only a few. There was more than one day, though, when he invaded my office, or White’s, or Gibbs’s, to lament the dwindling of humorous pieces with the growth of what he always called “grim stuff.”

Ross was always scheming to find more humorists. At one point he found a guy that he thought could write classic casuals, but the guy ended up turning in some ‘grim stuff’. Thurber reports Ross saying, “You find a guy that can write humor, and the first thing you know he turns in a piece about a man stumbling over the body of his wife on the floor, or something like that.”

The chosen one

J.D. Salinger completely changed the reputation of The New Yorker.

His stories in The New Yorker were part of a run of stand-outs that the New Yorker published in the late 40s. I’m talking not just about “The Lottery” and “Bananafish”, but also Cheever’s “The Enormous Radio” and Nabokov’s “Signs and Symbols” (published originally as “Symbols and Signs”).

However, the release of The Catcher in the Rye in 1951 was something else. This book was that rarest of things: a best-selling novel that was also critically acclaimed.

When his story collection, Nine Stories, came out in 1953, you had something even rarer: a short story collection that was a major seller. And seven of the stories had originally been published in The New Yorker.

This story collection cemented the New Yorker’s place as America’s preeminent fiction journal.

It’s true that there were other fiction journals in the 50s. There was The Saturday Evening Post, which still paid much more and had ten times the circulation of The New Yorker. If you were an award-winning writer in the 50s, you likely published your stories in The Post. That’s where, say, James Gould Cozzens (1949 Pulitzer Winner) or Nobel Prize winners Sinclair Lewis and Pearl Buck published their stories.

But although the fiction in The Saturday Evening Post might be popular and critically-acclaimed, it didn’t have the respect of the people who mattered.

This is the hardest thing to talk about, because it’s so intangible. But most writers in 1950s would’ve much preferred being J.D. Salinger to being James Gould Cozzens. Writers don’t necessarily care about winning awards: Salinger’s books never won any. Instead, they want the two things that matter most: popularity with the reading public and the respect of their peers. Very few writers truly manage to attain both these things. Merely winning awards isn’t enough, if it doesn’t come with genuine respect. Cozzens had the awards and the book sales, but he already felt old-fashioned—yesterday’s news.

Most commonly, writers who are respected by their peers tend to be less-popular with readers. There are legions of writers like Grace Paley or Flannery O’Connor—writer’s writers—who never caught fire with the general public.

But Salinger had both! He was popular and well-respected.

And The New Yorker was highly identified with his success. Many of the reviews of Catcher mentioned that Salinger was a New Yorker writer. And that association was cemented by the publication of his collection Nine Stories, consisting mostly of stories originally published in the New Yorker. There was a feedback loop here between magazine, critical success, and commercial success. He’d been introduced both to readers and critics by the magazine. This introduction had driven some initial interest in the novel, and the novel’s subsequent success increased the reputation of the magazine.

The New Yorker begins to anoint new stars

Starting in the 1950s, you begin to see this phenomenon of the writer who sells a story to The New Yorker, and now they’re instantly taken seriously by the literary world.

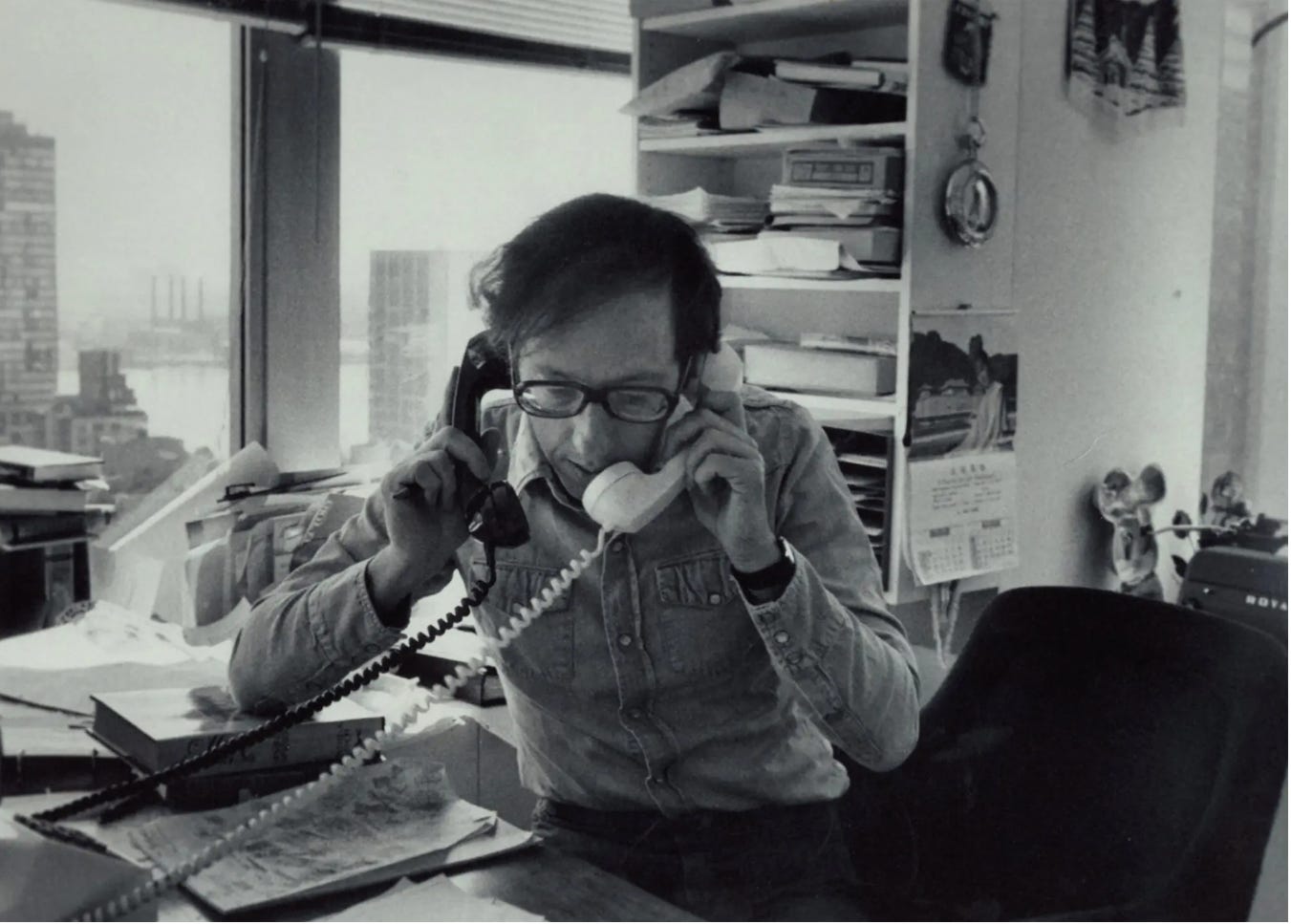

The best example of this phenomenon is Harold Brodkey. In 1953, he was one year out of Harvard. His wife was a family friend of William Maxwell, so Brodkey had some acquaintance with the editor. And then it turned out that Brodkey and Maxwell were on the same commuting schedule into Manhattan.

One day he handed his short story “State of Grace” to Maxwell on the train. In Brodkey’s Paris Review interview, he relates what happened next:

[Maxwell] read it and telephoned me that day. He was crying. He said it was good, that he didn’t think The New Yorker would publish it though he’d see that someone else did....Anyway, The New Yorker bought the story. It was called “State of Grace.” The New Yorker was not really my taste. I probably preferred Partisan Review at the time, but The New Yorker was more American, it used better English; it certainly was more flexible politically. But it wasn’t the place I’d dreamed of to publish in. So it happened. And The New Yorker has been my home ever since. Life is very odd.

Because of this ongoing relationship with The New Yorker, he sold a collection and got a series of ever-increasing book advances for a novel that didn’t appear for another thirty years. This guy had a career in part because William Maxwell picked him.

So the journal became respectable?

As The New Yorker grew in importance and respectability, there was increasing discussion about the so-called “New Yorker story”. The editors of The New Yorker claimed there was no such thing, but many critics throughout the fifties and sixties had a very different opinion.

This becomes clear when you read the reviews for the three retrospective collections issued by the New Yorker between 1940 and 1960. Even when these reviews are positive, they tend to be somewhat defensive in their praise.

For instance, a New York Times review of the second New Yorker fiction anthology, covering 1940 to 1949, started by saying:

Is there a New Yorker formula for the short story, a visible pattern in the carpet? That question has probably agitated many a grave session of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in its Manhattan headquarters up near the Albany end of the island, and interrupted many a match game in the most intellectual midtown saloons.

This reviewer, Charles Poore, insisted the answer was ‘no’, there was no New Yorker formula. A New Yorker story had no pattern besides one: its high quality. This reviewer insisted that America’s best short stories “are appearing in the pages of The New Yorker.”

Many reviews of these three anthologies say the same thing. People claim these stories are all the same, but it’s not true! This was the standard way of defending the journal.

This is certainly the tack that the editors took when they were questioned. Amy Reading reports how White defended the journal in a 1947 letter to a contributor:

“I can’t find any other publication that has offered within a three months’ period as wide a variation in types of fiction, or in styles of writing, as we have since the first of May, for example, with stories by John Cheever, Kay Boyle, Christine Weston (“Her Bed Is India”), E. B. White, John O’Hara, Niccolò Tucci, Nancy Hale, and Isabel Bolton.” [White] claimed that the only writers the magazine refused to publish were “the pretentious, the totally incomprehensible, and the obscene.”

Almost fifty years later, we find fiction editor Frances Kiernan defending the journal in exactly the same terms:

So far as I could see, there was no such a thing as a New Yorker story. How could there be when you had writers as different as Edna O’Brien and Donald Barthelme, Garrison Keillor and Stanislaw Lem, Bobbie Ann Mason and Max Frisch, Jamaica Kincaid and William Trevor, Deborah Eisenberg and John Updike, Cynthia Ozick and David Plante?

Lost in the whichy thickets

But many critics were willing to argue the opposite. In a 1950 review of the New Yorker anthology’s second edition, Delmore Schwartz, writing in The Partisan Review, launched a full-on takedown. His particular focus was on the style of The New Yorker. He said that good writers, when they wrote for The New Yorker, often adopted a style that was much less ambitious than their style when they wrote elsewhere. And that this style flattened their range of expression:

The periodical style which now characterizes the New Yorker excludes or dismisses various important kinds of perceptions, attitudes, and values, no matter how great the good will of the editors.

But the most famous takedown of the New Yorker’s fiction section came in 1965, when Tom Wolfe claimed in a New York magazine essay (“Lost in the Whichy Thickets”) that The New Yorker was full of sentimental dreck for women:

The short stories in The New Yorker have been the laughingstock of the New York literary community for years...Usually the stories are by women, and they recall their childhoods or domestic animals they have owned. Often they are by men, however, and they meditate over their wives and their little children with what used to be called “inchoate longings” for something else.

He insisted that the best fiction journals in America were The Saturday Evening Post and Esquire, where it was possible to find short stories with the “vessel-popping, hungry-breasty suffering, Freudian sex-mushed swooning” that was currently excluded from the pages of The New Yorker.

And Tom Wolfe was absolutely right about one thing: there was a widely-held opinion within the literary community that The New Yorker published boring stories. As Frances Kiernan, an editor in the fiction department between 1967 and 1988, put it:

[Often], some complete stranger, having learned that I worked at The New Yorker, would come over and begin to attack the fiction...It was too suburban, these self-appointed critics argued, too inclined to dwell on upper-middle-class mores and manners...In fact, they didn’t mind telling me that they themselves hadn’t read the fiction in years.

If the New Yorker story exists, is it bad?

But one critic attempted to make the case that there was a New Yorker story, and that this type of fiction was good!

In 1960, upon the publication of the third New Yorker anthology edited by Katharine White, a New York Times review attempted to defend the New Yorker formula.

The reviewer, Arthur Mizener, wrote:

“The New Yorker generally limits itself to stories that are conventional in tone and deal with familiar aspects of urban, middle-class American life.”

Mizener says that a New Yorker story consists of two things: a simple subject that can be easily understood by the upper-middle-class reader (i.e. the commuter or the shopping lady); and a casual, knowing tone—a voice that is so quiet that it seems to bear very little mark of the individual author.

This combination means that it’s only possible to tell a limited range of stories, but when the New Yorker sticks to these stories, it is often very good. Mizener claims many of the best New Yorker stories are about a sensitive person who encounters a coarse, conventional world. He identifies Frank O’Connor’s “Man of the House” as one of these stories. In this story a young boy gets invited by his friend to peep at a neighbor couple having sex. But the protagonist is so overcome by the couple’s humanity that he’s not really able to enjoy the spectacle on a sexual level.

In his review, Mizener closes by saying that although its range is limited, the New Yorker is obviously a good thing. The fact that it’s possible to publish such sensitive stories for such a large audience is great! He does not feel, as Schwartz or Wolfe do, that these stories are mawkish, or that they uncritically uphold bourgeois values. Instead he feels (as I do), that there is something very subversive in their unsentimentality and lack of affect. The reason these stories have lasted is that they present these situations without judgment, which means they invite you to judge for yourself.

On a sidenote, it’s not uncommon for critics of the New Yorker story to accuse it of being sentimental. Tom Wolfe certainly takes this tack in his takedown of the journal. I don’t think this accusation is totally fair, but it’s understandable. The New Yorker story aims for a striking effect in its final lines, and often relies on very simple oppositions, like the one between the sensitive kid and his friend in the Frank O’Connor story. I can see how this might feel manipulative.

Mizener makes a similar point in his review, saying that the best New Yorker stories are the ones that are ‘controlled by an insight of great depth’—in other words, the story makes a point that’s simple, but not cheap. It says something that feels deeply true. New Yorker stories fail when authors are skilled in creating the form of these stories, but they don’t have the perspicacity needed to provide any genuine insight.

He identifies John Cheever’s “The Country Husband” as a story that feels shallow, saying, the relationship at the heart of the story never becomes “the passionate self’s rebellion against ordinary life that he is apparently meant to be. [The protagonist] is only a suburban philanderer, and the attempt to claim more for him only make him look foolish.”

Mizener closes his review by saying:

Within the probably necessary limits it sets, The New Yorker publishes stories that are as good as any being written, by a variety of writers. When a magazine that is immensely successful with a wide audience can do that, it is either downright embarrassing or remarkably encouraging, depending on where you stand.

The New Yorker was very weird

Admittedly Mizener was mostly impressed by the size of the magazine’s audience—he was astounded that something so well-made could have such a large readership. I have the sense that if The New Yorker hadn’t been so popular, he wouldn’t have bothered to study it.

In 1960, when Mizener was writing, the magazine had a circulation of maybe 400,000. By some lights, that is not particularly high: it was less than a tenth of the circulation of The Saturday Evening Post. Even Esquire’s circulation was higher, maybe 600,000.

But the way The New Yorker treated fiction was completely different from any of these other journals. Remember, The New Yorker didn’t (and to this day still doesn’t) have any cover-lines: the magazine’s cover gave no hint about the issue’s contents. In this era, The New Yorker didn’t even have a table of contents—they wouldn’t add one until 1969. That meant you just opened the magazine and started reading. You had no idea what was in it.

The magazine was meant to be an experience. At the beginning, you had the unsigned sections, Goings On About Town and Talk of the Town. And these sections were written in their own unique style that I don’t have time to describe in detail. Goings was a precis of cultural events in New York, while the Talk was a series of short human-interest stories—Talk stories were often written in the first-person plural and had an insouciant, all-knowing tone.

Most people probably skimmed the Goings, then read the Talk. And, after that, they came to the fiction.

And the fiction section was also quite peculiar. Generally the first story would be a humorous piece, something by S.J. Perelman or James Thurber or E.B. White or Peter De Vries. Something light. This was called the ‘B’ slot. Then there’d be a more serious story, the ‘A’ slot. That’s where all the stories we’re talking about were published: John Cheever, Harold Brodkey, Mavis Gallant, J.D. Salinger—they usually got published in that spot. (There was also a ‘C’ slot, but that’s too complicated to discuss now.)

Then, after the ‘A’ story was done, there’d be the serious non-fiction pieces and the rest of the magazine. Every other section also had its own quirks—a bunch of stuff that I know way too much about at this point. The whole magazine was relentlessly strange, none of it was normal. None of it resembled anything you’d see in a regular journal.

And that strangeness extended to the presentation of the pieces. None of the pieces had the author’s name on the first page! There was no initial byline! Instead, they just had a title and then they launched anonymously into the story. And you only got the author’s name after a dash, at the very end of the piece. That meant until the story was over, you had no idea who you were reading.

This was not normal! Other journals advertised their writers. In Esquire and The Saturday Evening Post, you knew right away whose work you were reading. Often their names were right on the cover!

In The New Yorker, you really had no idea. You had to wait to find out the author’s name. Sometimes people could probably tell. Other times, they likely flipped to the end to see. But a lot of people—a surprisingly large portion (I’d bet)—just kinda glanced at the story, and if they enjoyed the opening then they’d read it through and only know at the end who wrote it.

That’s so weird! This system grew up very slowly over time. Initially, the pieces were quite short. The casuals often didn’t take up a whole page. You wouldn’t want to waste a lot of time calling attention to the author of something so short and not meant to be taken seriously. So you signed them at the end, like you’d sign a sketch.

When the stories started getting longer, White and Ross discussed dropping this convention and putting the author’s name at the front, but they never got around to it, and this design quirk became part of the New Yorker’s signature style.

Everything about The New Yorker feels the same way. Very fusty and particular. The journal was its own ecosystem, and some writers lived for decades in the interstices of its particular sections.

Why didn’t they just publish the best stories?

The history of The New Yorker is full of well-respected authors that submitted their stories fruitlessly: Norman Mailer, Joseph Heller, Richard Yates, Flannery O’Connor, Ralph Ellison, Jack Kerouac, William Gass. It also contains numerous fiction writers who were published only intermittently or published and then dropped: Langston Hughes, Shirley Jackson, Grace Paley, Raymond Carver.

These are huge names that are glaring omissions from their roster.

Then, on the reverse side, there are the New Yorker ‘house authors’. These are writers who appeared frequently in The New Yorker, sometimes publishing twenty or thirty or fifty or a hundred stories.

When I talk about ‘house authors’, I am talking mostly about the authors who wrote longer, more-serious stories (‘A’ slot stories)—not the writers who mostly appeared in the magazine with humor pieces or sketches. These sketch-artists and humorists tended to receive a lot less critical attention, and I don’t think they’re a major part of the debate about the literary merits of the New Yorker story.

So by ‘house authors’ I really mean writers like Nadine Gordimer, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, Elizabeth Taylor, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Mavis Gallant, Kay Boyle, Shirley Hazzard, Harold Brodkey, Peter Taylor, Jean Stafford, John Updike, John Cheever, William Trevor, Maeve Brennan, Frank O’Connor, and Edna O’Brien (among others).

And these ‘house authors’ derived major benefits from their association with the magazine. For one thing, it was a form of advertising. Every time one of your stories appeared, four hundred thousand people would get re-introduced to your voice.

But money was also a major benefit. Cheever supported his family for two decades mostly on money the New Yorker paid him for his stories. John Updike said if he sold them six stories a year, then that money would be enough to live. Mavis Gallant subsisted in France for like fifty years on what The New Yorker paid for her 120(ish) stories in the journal between 1950 and 1995.

Something akin to a job

The magazine also offered its regular contributors a modicum of stability.

The New Yorker had this very complicated system that I know way too much about, where they gave their favored authors a first-look contract. If you signed this contract you had to send The New Yorker all your best stories and give them right of first refusal. And there’d be bonuses in this contract if you sold them four or six stories in a given year.

If you had this contract, you got paid substantially more for your stories. But one of the oddities of the New Yorker was that you never quite knew how much money you’d get paid for a story—they would just send you a check for some weird amount! What relationship this bore to your story and your contract was unclear.

Because of this system, it’s impossible to say exactly how much they paid per story, but during the fifties Cheever seems to have gotten around $1,000 for a longer story (equivalent to about $12,000 today). Most authors weren’t selling them enough stories per year to live solely off this one magazine, but some obviously were. And even for the rest, the money was a big contribution to the bottom line.

The New Yorker would also often loan its contributors money, as an advance against future acceptances. The amount they’d loan you was capped, but I’ve seen it stated in a few places as $2000 (roughly equivalent to $24,000 in 2026 money), which is an insane amount to give someone as an unsecured no-interest loan that they might never have to pay back.

That relationship was surely very attractive. This magazine was literally loaning you money! Obviously they expected you to be around for a while.

3. The pleasures and perils of the ‘house author’ position

This New Yorker house author deal came with a lot of money—potentially enough to support your family. But it also came with cachet. If you got one of these first-look agreements, you were literally in the same club as J.D. Salinger.

No other magazine was really offering that. The only other mass-market magazine with a high critical reputation was Esquire. This journal was generally quite well-respected—I mean, Esquire was the magazine that had published Hemingway’s “Snows of Kilimanjaro”. But...Esquire was a monthly. That meant they published many fewer stories per year. They had to spread around the love. They could publish a Cheever story sometimes, but he wasn’t going to feed his family by writing for Esquire.

So what else? There was The Saturday Evening Post, but...its reputation wasn’t great. They were old, stale, boring. Nobody even bothered debating about whether there was a ‘Saturday Evening Post’ story, because nobody cared (and the journal would collapse in 1969).

The New Yorker was a weekly magazine that had made a big commitment to fiction. At least one serious story every week. There was a lot of amusing squabbling at The New Yorker about placement in the magazine, because everyone knew there was an ‘A’ slot where the good stories went. So there were 50 ‘A’ slots a year. Plus plenty of ‘B’ and ‘C’ fiction if you learned how to write for those sections (once he arrived on the scene, Donald Barthelme’s stories usually got put in the ‘B’ slot).

If you were an ‘A’ slot regular, then it usually meant you could release a story collection, and it meant there was a huge amount of interest in publishing your novels. Being an ‘A’ slot regular also meant that when your book came out, it would get reviewed in most of the major periodicals. If you published regularly in The New Yorker, then that by itself was enough to give you a career.

But there are doubts about these authors

However, when these ‘house authors’ published a book—a novel or a collection—that was when the critics weighed in. Critics often acknowledged the worth of these authors, but there was still a niggling suspicion: if The New Yorker wasn’t publishing them so frequently, would we even be talking about this writer?

During the fifties and sixties, there was a lot of debate about the merits of these ‘A’ slot regulars. And that debate took various forms. The first was about whether the actual stories they published in The New Yorker were any good. The second debate was about whether these people were particularly good writers even irrespective of their New Yorker stories.

Like, this guy, Cheever, who we’re talking about. He is the classic example of a guy who only had a career because he wrote for The New Yorker, and whose work was discussed in exactly that way. And I’d say that, during the fifties and sixties, the consensus about Cheever was that his novels weren’t good, and his stories were second-rate.

However, because of the nature of Cheever’s career, it was difficult to fully dismiss him.

Other New Yorker fiction writers (Irwin Shaw and John O’Hara) struck it big with novels that were ultimately derided as overwritten and melodramatic. If you really succeeded with a novel that people agreed was bad, then it was safe to call you a hack.

But John Cheever wasn’t like that. His novels only sold moderately well. And the novels were so formless that you couldn’t really call them commercial.

Nor could you really say that he was a fraud or that he was overrated, because you knew he wasn’t actually particularly well-respected. There’d really be no point in working yourself into a lather over John Cheever’s mediocrity, because not that many people thought he was a great author in the first place.

The problem was that Cheever kept releasing these novels. And the novels were bad. But they were basically an epiphenomenon. When these novels came out, they only got discussed because of the stories. He was really a story writer.

But then you had to wonder: were the stories really that good?

When the collections came out, the reviews tended to say, “This is good, if you like this kind of thing!”

Was anyone reading Cheever?

But how many people actually liked them? Most of the collections would go out of print after a year or two. The most charitable response would be that Cheever’s audience consisted of New Yorker subscribers, and they didn’t feel the need to buy something they’d already read. But what’s equally likely—at least from the standpoint of an observer in the 1960s—is that Cheever doesn’t actually have very many fans.

Yes, he has readers, but...he isn’t a major draw. He doesn’t stand out. Wolfe includes his name in a long list of New Yorker writers and implies that the list is full of mediocrities. Later, when he mentions New Yorker writers that are actually worth considering, he mentions J.D. Salinger, John O’Hara, and John Updike—not Cheever.

It’s true that Wolfe doesn’t really read the fiction section of The New Yorker, but that’s the whole point. Cheever isn’t really making an impact; he’s got very little mindshare amongst the literati. That’s precisely what it means when these people say, “I skip the fiction.”

And that’s true for a lot of these New Yorker house authors. Like, all of these critiques of New Yorker fiction are basically critiques of these guys. When you talk about ‘New Yorker fiction’ you’re talking about the work of Peter Taylor, Mary McCarthy, Mavis Gallant, Sylvia Townsend Warner. These are the mainstays of the New Yorker’s fiction section. To critique the fiction in the New Yorker is the same as saying that these house authors tend to be bad.

In some cases, these writers are better known for their novels or nonfiction, so you can claim that actually they’re good writers, but their New Yorker stories aren’t good. However, people like John Cheever, like Mavis Gallant, like Peter Taylor...they don’t really have that excuse. Everyone knows that their literary reputation relies entirely upon these short stories that Tom Wolfe is deriding in his takedown.

The ‘house author’ is in a straitjacket

These house authors, meanwhile, are writers who’ve made a big bet on The New Yorker. They have learned how to write the kinds of stories that this magazine wants. That’s something they complain about repeatedly. In 1949, John O’Hara asks The New Yorker for a kill fee because he claims that if he writes a story for The New Yorker and they don’t take it, then nobody else will—because it would read too much like a rejected New Yorker story. (At some point, John Cheever makes the same complaint).

During the fifties and sixties, the New Yorker’s fiction is characterized mostly by what it won’t publish. It doesn’t want sex. Doesn’t go in for lyricism, stream-of-consciousness, self-referentiality, or other surrealism. And it wants a plain, journalistic style. There should be a minimum of plot. And The New Yorker prefers stories that gesture at an Olympian lack-of-judgment. You’re not told what to think, you just infer it from the events.

These strictures were pretty clear to most people reading The New Yorker. And they’re oftentimes clear when you read the rejection letters they sent to people like Jack Kerouac or William Gass or Joseph Heller, where they reject these writers for being too surreal or too druggy or too dark. And you can even see hints of these taboos in some of the things the New Yorker editors would say later in life, in their interviews.

For instance, William Maxwell said the following about his relationship with Cheever:

“The problem was, Cheever was really a modernist, and at a certain point fantasy came into his stories. At another point he abandoned the consistency of character. Characters in his stories did things which it was not in their character to do. He released them from this obligation to be consistent, recognizable characters. In doing that he was departing from Tolstoy and Turgenev and Chekhov. I couldn’t go with him. I think that the surrealistic work that he did is perhaps the most admired by a great many people, so I don’t feel I was right and he was wrong. It’s just that I couldn’t follow him there.”

Maxwell had his preferences. He didn’t love Cheever’s more-surreal stuff. That’s fine. Cheever could take that surreal stuff somewhere else.

This is totally unremarkable!

Every fiction editor has preferences. Every fiction editor has some vision for their contributors. There are a lot of editors who’ll let you know if you’re attempting something that’s not working. They’d much prefer for you to do something different instead. The history of the science fiction field is full of authors frustrated with their editors, and vice versa.

That’s what writing is. The editor has a magazine. They have to fill space in this magazine. And if they’re going to publish you, they need to be able to sell their boss on the idea that publishing your work will somehow meet the needs of this magazine.

With The New Yorker, the journal came under a lot of criticism from people who felt like the fiction section could somehow be bolder. But...William Maxwell didn’t believe in that criticism. His boss, William Shawn, also didn’t believe in the criticism. They were very aware of these critiques, but they didn’t care.

New Yorker readers, for their part, were generally unaware of these critiques, and it is unclear to what extent they even read the fiction.

William Maxwell made a very long-term bet on all of these house authors. He thought what they were doing was important and was worth publishing. But...he also believed that it was his job to push them to be their best.

This is a common theme in stories about the New Yorker. It feels merciless, like a grindstone. They’ll take a dozen stories, and then they’ll tell you that it’s not working anymore. You’ll send them more stuff, and sometimes they’ll take it and sometimes they won’t. This happened to Cheever in 1949—the New Yorker started rejecting a lot of his work. That’s why he switched editors from Gus Lobrano to William Maxwell. It also happened to Salinger in 1949 and to Shirley Jackson—after selling a few stories, they suddenly started getting lots of rejections. These editors would claim they still believed in you—they’d offer you these first-look deals like always—but they wouldn’t take what you actually sent them.

Some writers were shattered by this experience. Gilbert Rogin sold twenty-two stories to The New Yorker between 1964 and 1980. Then his editor, Roger Angell, rejected two stories, saying he was just retreading the same ground. Rogin was so upset that he never wrote another short story again.

Something similar happened to Mavis Gallant. In the 1970s, she was writing a series of autobiographical stories about her childhood in Montreal. Then William Maxwell retired, and she was switched to a younger editor, Daniel Menaker. He said, “When are you going to start writing real stories again?”

She said the gate to her childhood closed, and she could never write one of those autobiographical stories again. She recovered and sold many more ‘real’ stories to the New Yorker, but I wonder if part of the reason why she essentially quit writing in 1995 is that Daniel Menaker left The New Yorker, and she couldn’t bear to be subjected to the judgment of another new editor.

Some writers refused to play

Many writers opted out of this system, one way or another. After getting a string of rejections from the journal in 1949, J.D. Salinger temporarily retired from short stories to focus on his novel, The Catcher in the Rye. Sally Benson drifted west to Hollywood, got work as a screenwriter and stopped answering William Maxwell’s importuning letters begging her for submissions. Edward Newhouse made money in the stock market and decided he didn’t need to write anymore. John O’Hara and Irwin Shaw made money writing best-selling books and then eventually got mad at The New Yorker‘s demands and stopped submitting to them.

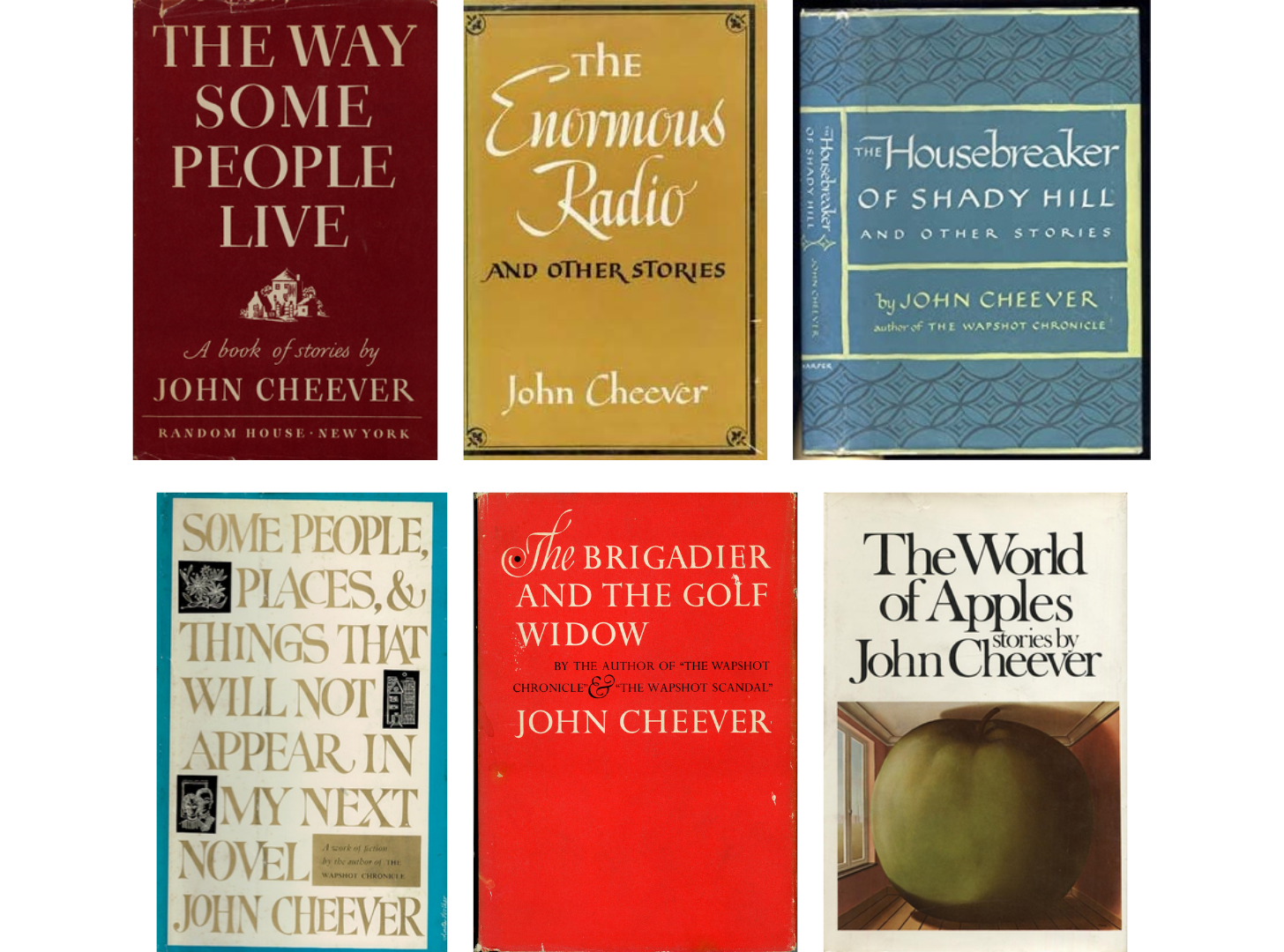

Cheever really wanted to opt out. He felt that being a New Yorker author was a kind of curse. His first collection, containing thirty of these early-period sketches that the New Yorker editors had encouraged him to write, was panned by the critics in 1943. One reviewer wrote: “To the extent that in the writing world any material—sketch, article, newspaper report, fiction—is called a story, John Cheever’s book … may be called a collection of stories.” Almost all the reviews stressed Cheever’s connection to The New Yorker and the dreariness of reading sketch after sketch after sketch.

He hated being dismissed as just a New Yorker writer, and he hated having to write these sketches that he didn’t think were worthy of his talents.

Cheever didn’t have many options

That’s why he spent so much time trying to write his terrible novels. Because he knew if one of these novels was a success, his life could be different.

But his true talent was for writing short stories. And if you were someone who was best at writing short stories, then there actually wasn’t a better deal than what The New Yorker was offering.

Many short story writers desperately wanted to take that deal. Flannery O’Connor, Grace Paley, Raymond Carver—they mostly collected rejections from The New Yorker. Although Paley and Carver would eventually break into the journal, it was clear this ‘house author’ position wasn’t really available to them.

(It’s worth noting too that the ‘house author’ position was emphatically not available to Black authors either. As far as I can tell, during the New Yorker’s first fifty years, they only published fiction by two Black authors: they ran two stories by Langston Hughes in 1934-35, and one story by Ann Petry in 1965.)

Cheever definitely could’ve taken his stories elsewhere. During the time he was most actively writing fiction, in the 1940s and 1950s and 1960s, there existed two other fiction ecosystems. The first was the world of university literary magazines. That’s where Flannery O’Connor made her career.

But Cheever wasn’t really academic. He was a high-school drop-out and never seemed to prosper in an academic environment. The people in this literary journal world mostly subsisted by teaching, and I don’t know that Cheever wanted that. He just wanted to write.

The other alternative was the world of mass-market commercial magazines. There were two types of mass-market magazines that published fiction. One group (Esquire, Playboy, Collier’s) mostly skewed male. Another group (Vogue, Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, etc) skewed more female. These magazines were mostly monthlies, so they published fewer stories than The New Yorker, but they also paid better and their standards were a bit lower. Some writers during this era made a large part of their living from selling to these magazines (Kurt Vonnegut is an example—he quit his job at GE after selling two stories to Collier’s).

Cheever certainly could’ve tried that...but these journals had their own issues. Many were folding. Many were decreasing their fiction output. This whole mass-market fiction world was slowly collapsing. And these magazines, by and large, had much more conservative tastes than The New Yorker. Sally Benson found this when she tried to write for Collier’s, they rejected a few of her stories, asking her for more upbeat endings.

It’s not that he couldn’t have switched horses, but it would’ve been a risk.

Cheever faced a decision point

There was a moment, in 1948, when Cheever could’ve diversified his portfolio. Earlier, in 1946, The New Yorker published a series of Cheever shorts centered on the same apartment building. The “Town House” series was adapted into a play. When this happened for John O’Hara with his “Pal Joey” stories or Sally Benson for “Little Miss”, the result was financial freedom. The success of those properties allowed them a little breathing room for the first time.

With John Cheever, that didn’t happen. The play got bad reviews, and it flopped. That same year, 1948, his editor at The New Yorker, Gustave Lobrano (he was J.D. Salinger and Shirley Jackson’s editor too) rejected four of his stories.

Cheever was in dire financial trouble, and he wrote a story, “Opportunity”, that he sold to Cosmopolitan for $1,750—significantly more than he was being paid per story by The New Yorker. He could’ve kept writing these mass-market stories.

Instead, he wrote “The Day The Pig Fell Into The Well”—a long, discursive story about a family’s vacation resort, and how this family persists in telling this one story about a day they had years ago, before the war, back when times were good. In the story, the war comes and goes, one of the sons dies, people suffer various losses, but they keep returning in memory to that one day, when they were all together—happy. The New Yorker took the story, to his surprise, since it was much longer and more structurally-complex than what he normally sent them.

Then he wrote one of his most famous stories, “Goodbye, My Brother”, about a group of siblings reuniting one year at their summer home. One brother hasn’t shown up in several years, but he arrives this time, and he’s full of various grievances that he keeps airing. The story is most notable for its strange, ambivalent ending—where the brothers have a fight, with blood drawn, on the beach, and then one brother goes for a swim in the ocean.

The New Yorker also took this story.

Remember, Cheever was required because of his first-look contract to send them everything first. If they had rejected these stories, he maybe could’ve sold them elsewhere. But they didn’t: they took the stories and published them instead.

Around this time, he fell out with Lobrano and switched in 1951 to William Maxwell, who loved this story, “Goodbye, My Brother”, and spoke warmly of it to the end of his life, saying it was his favorite story by Cheever.

But he persisted in trying to escape

During this time, Cheever wasn’t really focusing on short stories. His story productivity was actually unusually low. That’s because he was trying to write a novel. For years, since 1946, he’d been under contract with Random House to give them a novel. He still saw a novel as his way out. His contemporaries J.D. Salinger and Irwin Shaw both achieved a broader reputation (and financial security) by publishing best-selling novels.

But...he was blocked. Year after year, he tinkered with and threw away drafts of this novel. The reason for this blockage is unclear. But do you really need an explanation for why someone can’t produce a novel? It’s not weird to be unable to write a novel—most people can’t.

In Cheever’s case, there is evidence that he didn’t really believe in novels. He would often write in his journals that he thought the pace of modern life, with its dislocation and confusion, was more suited to a short story than to a novel (”The short story is determined by moving around from place to place, by the interrupted event.”) And when he had lunch with one critic, the man said Cheever came across as a “vivid, tough-minded short story advocate”.

Nonetheless, this was Cheever’s escape hatch: novels. He saw them as the only way of gaining a broader audience.

This became even more true after the appearance of his collection: The Enormous Radio And Other Stories. This book, which contained two of Cheever’s most famous stories (”The Enormous Radio” and “Goodbye, My Brother”) appeared in 1953, the same year as Salinger’s Nine Stories. A number of reviews compared the two collections and decided that Cheever had come up short.

Arthur Mizener (the guy who’d later defend the New Yorker story) said Salinger exemplified the best of the New Yorker story—Salinger transcended the limitations of the form. Meanwhile, he claimed that Cheever was “not a writer of any great talent” and that he was more cunning craftsman than true artist: “He does not so much imagine experience as have clever ideas for stories.”

The Chekhov of the suburbs

Because of these criticisms, Cheever kept telling himself he was done with short stories. He wasn’t gonna write these things anymore. And yet…he needed money. His novel wasn’t appearing. And he’d also moved in the meanwhile to the suburbs, so he had some new material. In 1953, he began his string of stories set in suburbia.

“O Youth And Beauty” feels the most like a traditional New Yorker sketch. It’s about a man who was a track star in college. And at parties he gets drunk and does the hurdles around his living room. But then he falls down, breaks his leg, and slowly falls apart.

However the story is longer than the traditional New Yorker story, and it has a humor and a luminescence. The style has evolved. It feels more like Gogol than Chekhov. It has voice.

The first sentence is a perfect example:

AT the tag end of nearly every long, large Saturday-night party in the suburb of Shady Hill, when almost everybody who was going to play golf or tennis in the morning had gone home hours ago and the ten or twelve people remaining seemed powerless to bring the evening to an end although the gin and whiskey were running low, and here and there a woman who was sitting out her husband would have begun to drink milk; when everybody had lost track of time, and the baby sitters who were waiting at home for these diehards would have long since stretched out on the sofa and fallen into a deep sleep, to dream about cooking-contest prizes, ocean voyages, and romance; when the bellicose drunk, the crapshooter, the pianist, and the woman faced with the expiration of her hopes had all expressed themselves; when every proposal—to go to the Farquarsons’ for breakfast, to go swimming, to go and wake up the Townsends, to go here and go there—died as soon as it was made, then Trace Bearden would begin to chide Cash Bentley about his age and thinning hair.

That is one sentence: two hundred words long.

When he’d finished the story, Cheever wrote in his notebooks: “It seems alright to me. God knows I need the money.”

Over the next ten years, he wrote a string of stories—often set in suburbia. These stories were fit in between other things, other novel projects. His story productivity was lower than during the 1930s and 1940s—he sold the magazine fewer stories, but the stories were longer and his rate was higher, so he still got paid substantially. Several years, he sold them more than four stories and got the 25% bonus payment (for each story) that was written into his contract.

And he wasn’t getting rejected nearly as often. His new editor, William Maxwell, was a huge fan. Maxwell often described his “rapture” when he first read a draft of another famous Cheever story, “The Country Husband”. He grew to believe that Cheever was one of the finest writers in America.

Cheever wasn’t writing New Yorker sketches anymore. His writing wasn’t slight or small. He often worked months on these stories (three months on “The Country Husband” alone). He had found a way, at least for a while, to fit his talents and ambitions into The New Yorker’s ‘house author’ system.

But there was a cost.

His last editor at the New Yorker, Gustave Lobrano, was more amenable to surreal work. He had accepted Cheever’s “The Enormous Radio” (about a couple whose radio starts playing the conversations in other apartments in their building) and “Torch Song” (about a man who befriends the spirit of death).

But Cheever’s new editor didn’t go in for that stuff. Maxwell was the editor who’d argued against publishing Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” (Lobrano had gone to the head editor, Ross, to overrule Maxwell).

Maxwell really cared about detail, about the specifics of things. He often pushed his authors to get closer and closer to real life. He was famous, in fact, for encouraging his writers to write “reminiscence”—first-person stories that would be read as autobiography. He persisted in buying these stories even after the New Yorker’s business department identified reminiscence as a drag on the bottom line.

And Maxwell had a vision for Cheever’s career. He believed he was publishing someone continuing the realist short-story tradition of Chekhov: finely-honed observations that told the truth about the world as it really was.

For his part, Cheever couldn’t really afford to stray too much from his lane. He often took months to write these stories, and he couldn’t afford to write any that didn’t sell. Moreover, many have noted that there’s a bit of a plaintive quality to his letters with Maxwell. He was desperate for his editor’s approval. Later, Cheever would feel petulant about this. He would say, of Maxwell, that the man mistook “power for love.”

Maxwell had power over him. Maxwell controlled his entry to this New Yorker ‘house author’ system. And this system was the basis of Cheever’s career.

The novel arrives

Cheever’s first novel, The Wapshot Chronicle, finally came out in 1957. Everyone commented on its episodic, fragmentary nature: it felt like the kind of novel that a short story writer would write. The New York Times panned the book:

THE NEW YORKER school of fiction has come in for so many critical strictures lately that one almost wishes John Cheever, a talented member of this group, would confound the critics and break loose...

This critic concluded that the novel was a failure. The novel came off as a series of sketches, which didn’t hang together like a novel or provide the satisfactions of the short story.

But many others reviewed the book more respectfully, and it sold relatively well, moving 20,000 copies in hardback and 170,000 in paperback, and winning the National Book Award in 1958.

However, the pressure wasn’t entirely off. Cheever’s advance for his next book was roughly $7,000 (90k in 2026 money). In 1960, he wrote in his journal that he was going to write no more stories. He was going to devote himself to novels.

But novel-writing was hard. He kept returning to the short story form. But now he was taking more risks. That year he wrote, “The Death of Justina”, a darkly-comic story about a woman whose cousin dies in her living room. This woman and her husband call around seeing where the cousin can be buried, but discovers that it’s essentially illegal to bury or transport a corpse in his town.

From Maxwell’s point of view, this wasn’t good. This was absurdism, not realism. He rejected the story. Cheever wrote, “Bill says the satire lacks support.” (The story later appeared in Esquire).

Cheever had gotten a few other rejections from Maxwell, but they were mostly for stories he regarded as second-rate. “The Death of Justina” was different. He knew this story was one of his best, and he knew that Maxwell had been wrong to turn down this piece. For the rest of his life, at readings, this was the story he’d read, and afterward he’d announce that The New Yorker had rejected it (“They thought of it as an art story,” he’d say)

Conflict with The New Yorker grew. I won’t rehearse the beats, but there was another story—“The Brigadier General and the Golf Widow”—that Maxwell also thought was too absurd. He printed it eventually, but not before trying to make changes to the ending that infuriated Cheever.

The telephone story

Finally, Cheever wrote his finest story: “The Swimmer”. This is the story about a man who swims through a series of neighborhood pools, growing steadily older, as his life falls apart.

This story was originally going to be a novel. He took 150 pages of notes for the book. But over the summer of 1963, Cheever boiled it down to a single story.

There are two stories that’re told about the publication of “The Swimmer”. The first is that Maxwell had reservations about publishing it, because he thought it was too surreal, too magical—however Cheever successfully argued him into buying the story.

And the second is that after they accepted the story, Cheever staged a confrontation, asking for a raise in his per-word rate.

For the rest of his life, Cheever would tell a story about this confrontation. He would say that William Maxwell handed him a telephone and told him to go out and get a better offer, if he could find one. Cheever claimed that his agent, Candida Donadio, called The Saturday Evening Post, and they offered Cheever a $24,000 a year contract for four stories a year (the equivalent of something like $300,000 a year). The New Yorker, in contrast, offered to pay him $2,400 for the story, and for some reason, inexplicable even to himself, he took the deal and let them publish the story.

This story (which Cheever repeated many times) doesn’t totally hang together. If Cheever already knew that Maxwell had reservations about publishing the story, then why would he choose this moment to demand more money?

But what is true is that The New Yorker could’ve paid him much more, if they’d wanted to.

Later, when writer Ben Yagoda looked through the New Yorker’s files to find the truth of the matter, he found that Cheever actually was underpaid. His per-word rate at the magazine was half what Irwin Shaw got, and less than a number of lesser-known authors.

Many people have said that Cheever should’ve taken the Post’s offer (never mind that the Post would soon fold, closing entirely in 1969). His daughter would always say she didn’t know why he let the New Yorker cheat him that way.

But…

I really think this misses the point. It ignores the context. And the context is: Cheever wrote New Yorker stories.

All his life, Cheever was regarded as a New Yorker writer. Indeed, he was often considered somebody who’d been ruined by the tastes of The New Yorker. When the magazine wanted sketches, that’s what he wrote. And when their tastes started to expand, he developed a new form of fiction, with the brevity and cold judgment of a sketch, but which took place in a warmer, more lived-in world and that used a much more playful voice.

The demands of The New Yorker determined what Cheever wrote. Maybe he could’ve learned to write Saturday Evening Post stories. Maybe. We don’t know. But submitting to the Post was always something he could’ve done, and he didn’t want to. The reason is obvious: he didn’t respect the Post. Nobody did. He didn’t want to be a Post author. He didn’t necessarily want to be a New Yorker author either, but at least he was willing to be one.

That, to me, is the genius of The New Yorker. It specialized in a form of fiction—the New Yorker story—that was capacious enough to accommodate the individual ambitions of a genius.

This form of fiction wouldn’t have necessarily existed without The New Yorker. In its own way, this form of fiction was as unique as Talk of the Town. It’s an instantly-recognizable form of fiction. It’s marked both by its accessibility, and the fact that it holds the reader at a slight remove.

Many New Yorker stories felt like they could’ve been written by another author entirely. There was a sense of familiarity about them. You could start reading them without knowing who wrote them. If you became familiar enough with this genre, then it was pleasant to see how each story would innovate slightly upon the basic formula.

These innovations took many forms. To Maxwell, Cheever’s main innovation was his setting: the New York suburbs. This suburban life was somewhat new, and Cheever really seemed to capture the experience of an entire generation (many New Yorker writers and editors also lived in these suburbs, including Maxwell himself). Other writers also had their narrow lanes: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and Christine Weston wrote about India; Emily Hahn about China; Mavis Gallant wrote about expatriate life in Europe (editors often encouraged her not to write about her home-country, Canada); Mary McCarthy wrote about her orphaned childhood; Peter Taylor and Nancy Hale wrote about the South.

John Cheever also developed a distinct sensibility that was very playful and inventive, but this sensibility was often not apparent if you only read a few of his stories. The New Yorker didn’t allow writers to be too unique or to develop too much of an individual voice. To some extent, The New Yorker edited away their voice—particularly in the beginning, it was famous for its blizzard of editors, who’d mark up every page, moving words around, introducing the reams of subordinate clauses (what Wolfe called “the whichy thickets”) that characterized the New Yorker style. In Cheever’s case, there is evidence htat Maxwell would systematically downgrade his diction, substituting plainer words for Cheever’s original language—for instance, in “The Country Husband” Maxwell replaced ‘febrile’ with ‘overheated’, ‘tristesse’ with ‘dismal feeling’, ‘afterglow’ with ‘sunset’, and many other similar edits.

There is an active debate about how much editing was actively done. The New Yorker editors were sensitive to the charge that they edited away the writer’s individual voice, and I’ve now read many self-justifying defenses of their editing practices. But...the fact remains: these New Yorker writers tended to have very minimal voices. You often could not tell, just from looking at a paragraph, whether the piece was written by one writer or another.

I tend to think that a lot of this was simply done through selection. The New Yorker editors simply didn’t accept any stories whose voice was too unique (too ‘special’, as Katherine White would put it).

The New Yorker editors seem to have a double-consciousness about what they were doing. They understood that not every writer was right for The New Yorker, but...they also genuinely liked what they were publishing and thought it constituted the best short fiction in America. This kind of double-consciousness is common in publishing.

To me, the New Yorker story is characterized above all by its simplicity and detachment. You’re introduced in the first paragraph to a character. This character seems to be normal, but you know (because it’s a New Yorker story) that they’re secretly in some terrible pain. And over the course of this story, as you watch them go about their daily life, you’re going to perceive their variety of damage. And eventually you’re going to watch them suffer.

It’s a cold, cruel joy that the reader derives from these stories, but it is indeed a joy.

That’s the pleasure I got from the Mavis Gallant stories. There’s “Speck’s Idea”, about an art dealer who pretends (or is he pretending?) to embrace fascism in order to befriend an artist’s widow. Or “The Ice Wagon Going Down The Street” about a pair of social-climbers forced to look at the wreck they made of their lives.

It’s the pleasure I got from Alice Adams, who wrote at a much later period (the 70s and 80s) about liberated women in California, and their petty sadnesses. In “Ripped Off”, a lost-seeming hippy girl, Deborah, discovers that a burglar has taken the jewelry from her Russian Hill apartment, and after mulling over the incident, she decides not to tell her boyfriend about the incident. And in “Snow”, a father struggles to connect to his overweight daughter, who’s started dating another woman. They’re all on a skiing trip together, and eventually the story drifts out of his point of view, and the reader realizes that this guy’s opinions don’t actually matter.

These stories don’t openly indict their middle-class characters, but they invite the reader to indict them. We judge these people, even though they’re just like ourselves.

It is so much fun!

The New Yorker has published (and this number is true) around 13,000 stories. Of these, maybe 5,000 are casuals and humor pieces. But, out of the rest, at least several thousand fit the above formula (the reader is introduced to a hapless middle class person and subtly invited to judge them). It seems impossible that you can get so much mileage out of this formula.

But it is the truth. The New Yorker story exists, and it is very enjoyable to read.

4. Cheever ascends

After “The Swimmer”, Cheever essentially stopped publishing in The New Yorker. He was an alcoholic and found it increasingly difficult to write, while on the infrequent occasions when he submitted to The New Yorker, his stories were usually rejected.

His second novel, The Wapshot Scandal, was a sort of success. It landed his face on the cover of Time, at least. But there was a sense that he was really being rewarded mostly for his stories. In a review of Cheever’s second novel, Stanley Edgar Hyman wrote,

“When a highly-esteemed story writer tries a novel and fails at it, in this amazing country, he is rewarded just as though he had succeeded. … John Cheever’s The Wapshot Chronicle won a National Book Award. In The Wapshot Scandal, Cheever has again tried, and again failed, to make short story material jell as a novel. As a two-time loser, he can probably expect the Pulitzer Prize.”

I’m aware that I am really underselling Cheever’s novels here. I am sure they have some fans. But I personally found them all to be unreadable. They just have no life. Whatever quality is compelling in his stories, and which pulls you through from page one to twenty, is completely missing from his novels. From the first page, most of them are dreary.

His third novel, Bullet Park, was roundly panned. By 1976, all of his work (except his most recent collection) was out of print.

Then, in 1977, he had a late-in-life success with Falconer, the novel that is generally conceded to be his best. I also don’t like this story, which is a strange, surreal tale about a man who has a homosexual relationship in prison. But it’s definitely more readable than his other books. This book was a best-seller, and in the wake of its success, some of the reviewers started wondering how it was possible that all of Cheever’s short stories could possibly be out of print.

The seven-hundred pager

That year, his Knopf editor, Robert Gottlieb, had a great idea. He proposed assembling Cheever’s best short fiction into one huge, career-retrospective collection.

John Cheever apparently felt this idea was stupid. What was the point? All the stories had already been reprinted twice: once in The New Yorker, and for a second time in a series of six short story collections. All of the latter were now out of print, save for the most recent one, The World of Apples. So why bother reprinting the stories for a third time? Anyone who wanted them already had them.

But Gottlieb set to work. Cheever’s only stricture was that he didn’t want any stories reprinted from his first collection (the one with the thirty New Yorker sketches). But besides that, Gottlieb didn’t exercise much selectivity: he reprinted the entire contents of Cheever’s five later collections, and then he added a few other uncollected stories. Gottlieb’s genius really came in the arrangement. They pretended it was chronological, but it really wasn’t: the stories were arranged in order to speak to each other and provide an enjoyable reading experience.

The book launched with a bang. The New York Times review by Richard Locke is probably one of the most thoughtful and interesting reviews I’ve ever read. It lavishes praise upon this book, calling attention to its many pleasures:

He is tender. He has the rare capacity to move mature and intelligent readers to tears, and these readers are often men.