Will it last?

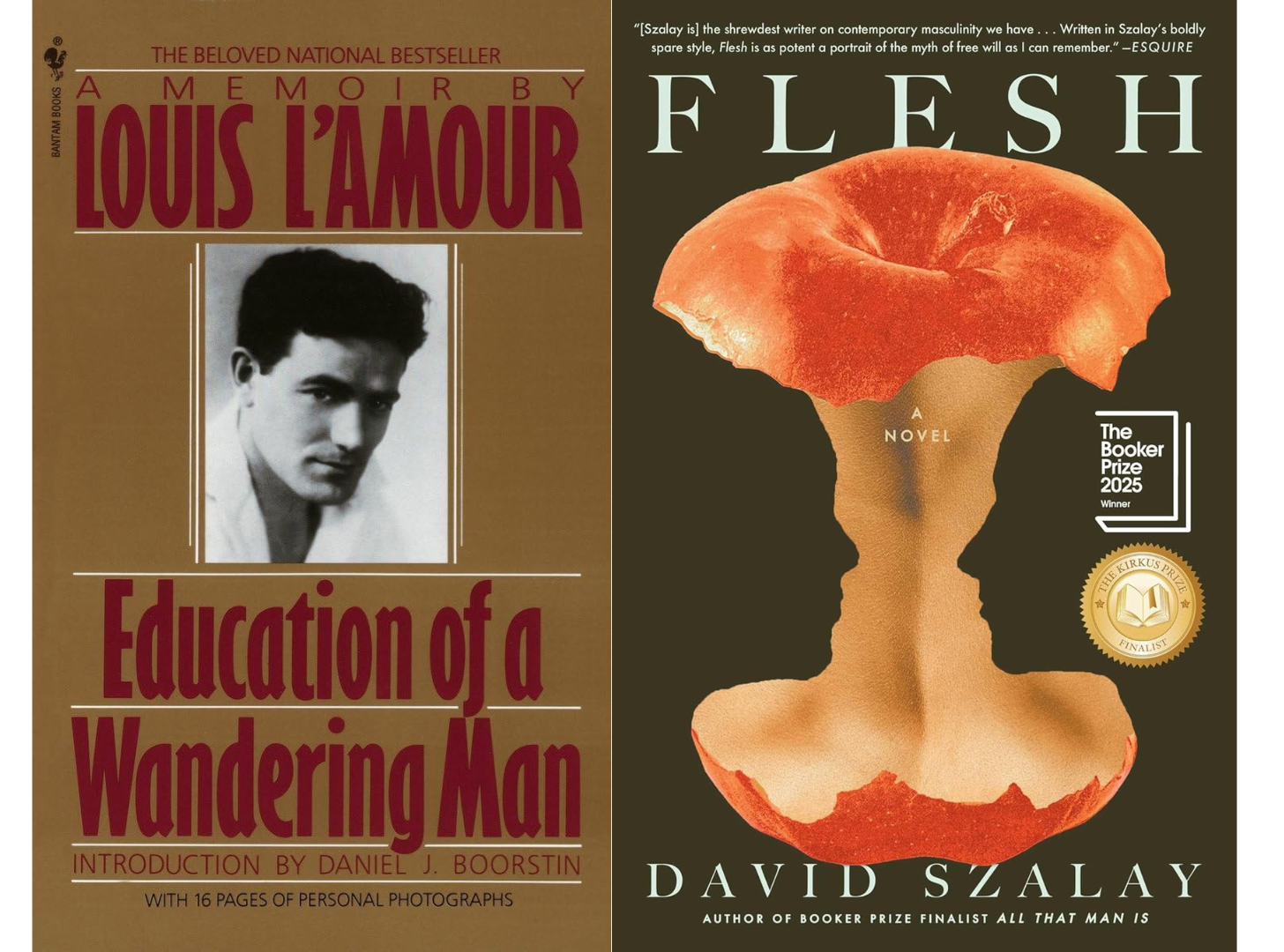

I belong to a real book club that really exists in real life. It is composed of my actual friends. We meet maybe four to six times per year, and it’s always a great time. Usually our books are picked by Dustin, who keeps a list of interesting books. But for our latest selection I lobbied hard for Flesh, because I knew both Celine Nguyen and Henry Oliver liked it.1

And I enjoyed the book. It rewarded the few hours I spent reading it. I did not think, “God what a waste of time.” That was a nice feeling. I hardly ever pick up a newly-released novel just for fun. Earlier this year, I read Ocean Vuong’s book because I thought it would be fun to write about. I also reviewed Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie’s Dream Count, which I did not like, although I think she’s a very good writer.2 Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection was the last contemporary book I read that I truly enjoyed, and that was six months ago.

Anyway now that Flesh has won the Booker Prize, I felt like I should write about it. This novel is not horrendous. When I started reading this book—the first chapter is about some kid in Budapest being seduced by an older woman—I was like what is this? What am I reading? This is so flat! I do not want to read 400 pages of this.

One day she suggests that they sit on the sofa.

He has never been in her living room. He doesn’t really take it in, except that there’s a balcony at one end, like there is in his mother’s apartment, with a balustrade made of panels of green safety glass.

They sit on the sofa.

But then a lot of exciting stuff happens. Actual events! It’s so shocking when I am reading a contemporary literary book, and then things happen. Like, major life events. And then different things happen. And it’s all related in this very flat tone, but the protagonist himself is not emotionless. He has desires. He just doesn’t really verbalize those desires or conceptualize them in various ways. It’s a very interesting performance on Szalay’s part. I appreciated the artistry and enjoyed reading the book. The Booker Prize was well-deserved!

The Buzzy Literary Novel

When I was trying to describe to my friends why they should pick Flesh for book club, I had difficulty explaining why it was supposed to be good. All I knew about the book was that Celine Nguyen had gushed about it. She’s told me many times about how great this book is. But Celine is a bit like my friend Courtney Sender, she’s all about the prose. And anytime someone talks about the quality of a book’s prose, I just tune it out.

In reality, I generally agree with Celine’s recommendations, just like I generally agree with Courtney’s recommendations. When they like something, I usually also think it’s good. But I’ve heard so many books described as ‘having beautiful prose’ when the prose really was not beautiful, so I tend to ignore the epithet.

Basically I had trust: I trusted Celine that it was worth reading. My book club also trusted me when I told them this was the cool book to read this summer. That’s because this book is part of a phenomenon—the buzzy literary novel—that my book club basically understands. Each year, there are some big hot books, and we often read these kinds of books, though not as often as you’d think (our previous pick was Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy).

This phenomenon, the buzzy literary novel, can only exist if it’s able to arouse the attention of people like me and Henry Oliver and Celine. To some extent, this institution is only perpetuated by our attention.

The other type of popularity

There is another kind of literary phenomenon that exists: the bestseller.

This phenomenon does not rely upon the attention of highbrow people like me. Generally, people like me are somewhat in opposition to the bestseller. Often the term ‘slop’ is lobbed around in relation to these bestsellers. Just this week, The Drift has posted a sneering take on a new category of bestseller: the romantasy novel. They do not worry that their audience might actually be composed of people who like romantasy: instead they describe the genre in anthropological detail, as if this is the first time people are hearing the name Sarah J. Maas. It’s not actually true, plenty of their readers know about Maas, but the conceit of the The Drift is that it’s for people who don’t read bestsellers.

I recently read a great book, Bestsellers: a Very Short Introduction, that gave a rundown on the last hundred years of best-selling novels. It was quite fascinating to see the ways that bestsellerdom has evolved. For instance, the success of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath inaugurated a whole slew of bestsellers focused on social issues, like Laura K. Hobson’s Gentleman’s Agreement, which is about a journalist who investigates antisemitism. This book was a monster hit, selling almost two million copies in 1947.

We don’t really have books like this anymore, bestselling novels that tackle an issue quite so squarely. The closest I can think of is Bonnie Garmus’s Lessons in Chemistry, which is in some sense about 20th century sexism and the way it thwarted women’s aspirations. But that doesn’t hit quite as hard as Gentleman’s Agreement, which was a book about now, about the very recent past.

Gentleman’s Agreement and Lessons in Chemistry are one kind of bestseller: the breakout book that sells bajillions of copies.

But there is another kind of bestseller, the best-selling author.

The world’s most successful writer of Westerns

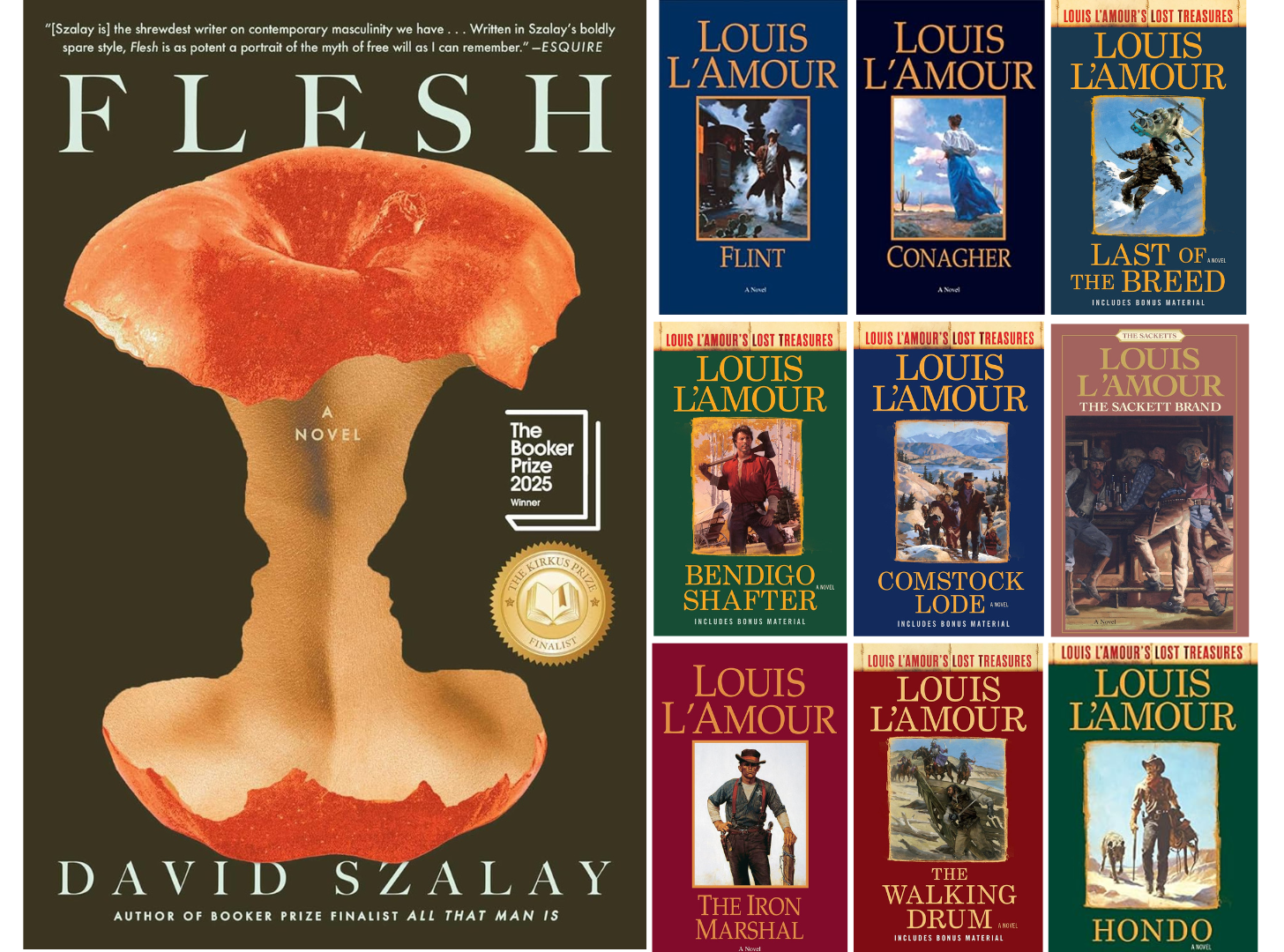

Recently, I made a strong attempt to understand the appeal of one of the best-selling authors of all time: Louis L’Amour.

Louis L’Amour sold over three hundred million books, almost all of them paperback Westerns. He is twenty-eighth in Wikipedia’s not-at-all-complete list of the best-selling authors of all time. And…I think it’s fair to say that even other writers of Westerns feel like L’Amour isn’t particularly good. Not a single novel by L’Amour is in the list of top 25 Westerns compiled by the Western Writers of America, and he only won the Spur Award (for best Western novel) once—Elmer Kelton won it six times over the same period.

It’s very funny because there was this huge audience of people who read Westerns. And those people generally loved L’Amour. He had passionate fans, people who read all of his paperbacks. If you look at reddit threads about him, you’ll see many posts where people are like, “My dad’s favorite author” or “My Great Uncle Clyde had a full set and was excited to share them with me”. Author Johnny Boggs (who has won ten Spur Awards) has a funny blog post about how at his events people will still come up and say that they really prefer L’Amour to him. There were lots of more-sophisticated and critically-acclaimed Western writers, but fans of those authors often tended to prefer L’Amour.

L’Amour’s fans were often men, and they were quite frequently cowboys and ranch-hands themselves. That’s what is attested in a lot of the threads about L’Amour and a lot of remembrances of him. These men spent a lot of time alone. They worked hard. And they read his books at the end of a long day to unwind. His peak popularity was really in the 1970s and 1980s, and they lived in isolated rural areas where there maybe wasn’t a lot of other entertainment.

L’Amour’s success is inextricable from the success of the distribution channel his books used. Almost all of his books were paperback-originals, which were sold on category-fiction racks in general stores, railway stations, news-stands, magazine kiosks, drug-stores and other such places (basically everywhere that you could buy newspapers or magazines). These places would often have a rack or spindle devoted just to Westerns. L’Amour was an early success in this format—for fortuitous reasons one of his first novels, Hondo, came out at the same time, in the same week, as a movie by the same name that was based upon the book. This success created a lot of name recognition for L’Amour, and he worked quickly, publishing a lot of books to capitalize upon that name recognition.

But he was held back by his publisher, Fawcett Gold Medal, who refused to publish more than one book a year by L’Amour. They felt that his popularity wasn’t sufficient, and they were wary of exhausting his readership.

Eventually, he persuaded one company, Bantam, to back him to the hilt—they agreed to release three books a year by L’Amour. His books almost always sold extremely well, for a paperback, upon initial release. And because most of his backlist was with Bantam, they had an incentive to keep his books in print. Over time, he grew to dominate a larger and larger part of the Western-fiction rack. If you picked a book at random from this rack, it would likely be his.

Between 1953 and 1980, he released something like eighty paperback-originals. He became a brand. Although many of his books were set in New Mexico or Arizona, he also had books set in Texas, Oklahoma, Montana, Alaska, and elsewhere. Over time he also started expanding outside the temporal boundaries of the Western. Most Westerns tended to be set between 1860 and 1880, but he started publishing books set earlier and earlier, including some set in colonial America.

Many of his books had a ranch-romance element: a lone cowboy or gunslinger comes upon a woman in peril; he protects her from the badmen seeking her land, and they fall in love. But he also some books that were more slice-of-life tales; he had some episodic adventures; he had a few that were mysteries and a few that were chase or survival stories.

It’s no mystery why he’s the best-selling Western writer of all time. There existed this audience of people who weren’t necessarily big readers but wanted cheap, reliable entertainment. And he was willing and able to meet these readers’ demands. These readers lived in rural areas that often didn’t have bookstores. But when these readers went into town to get groceries or liquor or prescriptions, they often encountered these racks of paperback books that had novels with covers and back-cover blurbs that were designed to entice them.

Increasingly, those novels also had L’Amour’s name on them. And if they enjoyed one of his books, they could always go back and buy another one. Yes, these readers often branched out and tried other writers, but if you were buying from these particular racks, you were probably buying a lot of L’Amour.

Imagine if Gillian Flynn was able to release three Gone Girl novels a year, and they were all of decent quality—she would dominate the domestic thriller market the same as L’Amour did the Western-fiction market. His readers certainly had some demand for novelty, but his books varied enough that he was able largely to meet this demand.

With L’Amour, I don’t think it’s truly possible to appreciate how he became a success unless you’re able to appreciate the paperback-Western distribution channel and the nature of his fanbase. It seems incredible that he could’ve had so many male readers and that his readers could’ve been so rugged, but it’s something that’s attested to many times. Jane Tompkins, in her study of Western novels, recounts encounters with three different men she met at a homeless shelter who were all huge L’Amour fans.

In my own mentions, when I asked online about L’Amour, Sherman Alexie said his dad was a ‘rez guy’ who loved L’Amour. And Joyce Reynolds said “L’Amour was a favorite amongst working cowboys and sheepherders I’ve known. Short, easy to read, something to unwind with after a day’s work or to read during the winter.”

L’Amour was like Law and Order, he was something that was always available and that would always be pretty good.

Much ambition, no respect

I was drawn to L’Amour after reading a profile of him by Smithsonian magazine. And in this profile it was clear that L’Amour was wounded by the lack of critical attention for his fiction: “I don’t give a damn what anyone else thinks, I know it’s literature and I know it will be read 100 years from now.” And even during his life, it’s clear there was a lot of bitter sniping from other authors about his success—so much so that his website feels compelled to address it.3

During 1960s, he wrote a historical novel called The Walking Drum, an adventure romance set in the 12th-century, about a Breton boy who gets carried off by pirates and makes his way, through cunning and bravery, first in the Islamic world, then on the Russian Steppe, and finally in Byzantium and Persia. L’Amour claimed he read over a thousand books to research this novel, and I believe it—time and again I’d google a book mentioned in the novel--something I’d never heard of before—and find it was a real text.

This novel was his bid to write a serious mainstream book that could be released in hardcover and which would get reviewed in the big presses. The model here wasn’t precisely ‘literary’—it was more like the historical fictions of Gore Vidal (the category we today would call ‘upmarket’).

But he received a long rejection for this book. He apparently found this rejection very shattering, and he set the novel aside for fifteen years. It was only in the 80s that he was finally able to break into hardcover, and that was the period when he released a series of experiments where he, for the first time, deviated from the tropes of the Western.

Since his books were so popular, and he had such high aspirations for them, I felt duty-bound to try and understand his work. I spent about a month reading nothing but L’Amour, and in the end came away with a strong appreciation for what was best in his ouevre, even though I do ultimately understand why he hasn’t gotten the literary acclaim he wanted.

The late L’Amour

The Walking Drum is an interesting novel, which attests to the breadth of L’Amour’s reading, but something about the writing feels a bit unsteady, a bit too modern for the 12th-century setting. I would say that the best of his late fictions was Last of the Breed, a Cold War thriller about a pilot who is shot down, captured, held captive in Siberia, and manages to escape. He makes his way through a cold, hostile country over the course of several years.

This book demonstrates, I think, one of L’Amour’s strengths, which is his belief in the continuity of human nature. He was excellent at understanding that all people are people. That they live in different societies, where they operate under different incentives, and sometimes those incentives put them into conflict, but that doesn’t mean there’s something essentially different about them.

In this book, he writes very sympathetically about a number of Russians. It’s late in the Cold War, few of them are communist true believers, but they’re not dissidents either. They’re just people, living in this society, trying to succeed as best they’re able.

One of the interesting things about this book is that the hero, the fighter pilot Joe Mack, is not white. He is a Sioux Indian. At one point, one of the Russians asks him, something like: Why are you fighting for America? Don’t you hate the white Americans?

“Why should I? My people came west from the Minnesota-Wisconsin border, and we conquered or overrode all that got in our path. We moved into the Dakotas, into Montana and Wyoming and Nebraska. The Kiowa had come down from the north and occupied the Black Hills, driving out those who were there before them. Then we drove them out.

“We might have defeated the Army. We fought them and sometimes we won, sometimes we lost. Only at the end did we get together in large enough numbers, like at the Battle of the Rosebud and the Little Big Horn. We might have defeated the armies, but we could not defeat the men with plows. They were too many.”

This is very true to how L’Amour views relationships between native Americans and white Americans in his Westerns. For technological reasons, white people are destined to win, but he does not view white Americans as being essentially better. And, indeed, like James Fenimore Cooper before him, in his books it often feels like the native Americans and the frontier settlers have more in common with each other than they do with the more settled Americans of the coasts.

The education of a best-seller

The L’Amour book I enjoyed most was his memoir, Education of a Wandering Man. L’Amour left school at fifteen and afterwards worked as a ranch-hand, miner and seaman during the Great Depression. All through this time he was reading many books on his own. This is the story that he tells in his memoir. It was a pleasure to read, much more engaging than any of his novels. In this book, his worldview came through in such a strong, muscular way, and I really enjoyed spending time with his voice:

Hunger I was to experience many times, but it was reassuring to know others had survived, although most written accounts of hunger are by those who never experienced it. Knut Hamsun is the only one I can think of offhand who wrote with any knowledge of the experience. In the movies one always sees a hungry man stuffing himself with food when first he gets a chance to eat. That’s ridiculous, of course, for a truly hungry man eats very slowly, savoring every bite, and is almost overcome by having food at last.

The voice of this memoir is blunt, but very warm—it really plays to his strengths. On a sidenote, it’s fascinating that of the three most famous writers of Western fictions—L’Amour, Cormac McCarthy, and Larry McMurtry—all played up their own image as bibliophiles who had immense book collections. In L’Amour’s case, it’s clear that writing these books was the result of a vast education: he mentions deeply engaging with the classics of both East and West, including some fairly obscure books (he mentions reading a translation of the Sanskrit classic The Ocean of Story). He read Nietzsche, Whitehead, Freud, Moliere, Turgenev, Victor Hugo, George Eliot and thousands more. The book is overflowing with his reactions to various books, in many genres, from many cultures. The one thing he almost never read was other Westerns—perhaps one reason why his fellow Western-fiction authors didn’t like him (he also didn’t like his books to be advertised as Westerns, he demanded that they be labeled ‘frontier fiction).

Anyway, I can’t imagine anyone will read this memoir if they’re not already interested in L’Amour, but I thought it was his best work.

I cannot wholeheartedly recommend L’Amour

I’ve been sitting on this post for months, because in truth I had a very mixed experience with L’Amour. I felt that if I was going to understand the Western, then I needed to understand L’Amour, and I liked some of his books (Last of the Breed and a few others) very much. However, I found it very difficult to find these enjoyable books, and my hit-rate with his fiction remained pretty low.

The first ones I read were some of his most popular, Hondo, Flint, and The Sackett Brand. They felt a little generic to me. Hondo and Flint are about lone gunmen who come across a woman in peril and ride to her rescue. The Sackett Brand is a revenge story about a man whose wife gets killed, so he hunts down her killer.

In these books, L’Amour’s writing can feel a thin, like we’re using stock pieces, stock sets, repurposed images that we’ve seen before. It just doesn’t feel like there’s a lot of heart. And because of that, there’s not much suspense either. All three books end in climactic fights, but it feels like there’s no real emotional stakes.

The fourth book, Conagher, I really enjoyed. It’s a slice-of-life story about a cowboy who slowly falls in love with an isolated widow. What makes the book better is its attention to the details of this life. Conagher is not some lone hero—he’s just a work-a-day stiff.

Twenty-two years...it was too long...and nothing ahead of him but a stiffening of muscles, growing tired a little sooner, finding it harder to keep warm. He’d driven spikes on the railroad, handled a cross-cut saw in a tie camp, helped to sink a shaft on a contract job, and helped to build a couple of mountain roads in Colorado. Then...he’d gone up the trail from Texas three times, and had punched cows in Texas, the Arizona Territory, Nebraska, and Wyoming. It was a hard life, a bitter, lonely life after a fellow got beyond the kid stage

Conagher proved to me that L’Amour can be good, but I found it very hard to identify beforehand which of his books were the good ones. I think the problem with L’Amour is that people who are fans of L’Amour tend to be fans of everything. They just read it all. And he wrote so many books that there’s not much agreement on what were his best. Nor has he gotten the kind of critical attention that would allow us to divide his books into different types and strata.

In my experience he has basically three types of books:

Action / Adventure

Historical Romance

Realism

But there’s no real external difference in how these types of books are packaged and sold to the audience. They all have back-cover copy that makes them look more or less the same. The action / adventure stories (like Hondo and Flint) have a more hard-boiled tone and a lot of action, but little character development. The historical romances have less action, tend to cover more ground, and often have far-fetched coincidences (for instance The Lonesome Gods hinges on a strange giant living in the mountains who is the long-lost son of the antagonist).

Personally, I found the works of realism to be the best, but it’s hard to separate these books a priori from the rest unless you know better. I feel comfortable recommending a book like Conagher or Bendigo Shafter or Fallon to anyone, but in order to find these books I also had to read a lot of books that were tedious, like The Sackett Brand and Lonesome Gods, or just middle-of-the-road like Hondo or The Iron Marshall.

No matter what I did—no matter how I scoured the internet to find a list of L’Amour novels that were actually good, I couldn’t do anything to improve my hit-rate: one out of three was really good, but it felt impossible to find that one without also reading the other two.

Nonetheless, L’Amour is actually doing better than most bestsellers. A lot of people still like this guy! Year by year, interest in him dwindles, but most of his oeuvre is still kept in print by his son (who’s recently released Kindle editions of all his books), and there’s plenty of chatter about him online.

L’Amour chose his own fate

I don’t have a lot more to say about Louis L’Amour. Ultimately, I concluded that his popularity was really tied to a way of reading and a type of reader: the sort of person who doesn’t read many books, falls in love with a certain author, and reads everything they’ve written.

In order to sell books to this type of reader, Louis L’Amour’s estate has purposefully obfuscated the differences between his books—making them seem as similar as possible. That’s a choice that they made, and it was a choice L’Amour made, to write so many books in the same genre, instead of branching out in the way he was clearly capable of doing (i.e. with Last of the Breed).

There’s nothing wrong with this kind of writer or with this kind of reader. I certainly don’t regard them as a morally deficient ‘slop’ eater. But I also cannot share L’Amour’s conviction that the literary world has done him wrong. I do think that if you want literary acclaim, you need to start identifying some of your books as being better than the rest, and you need to do your best to market those books as being superior.

In his case, he did do that in his last decade of life—perhaps if he’d lived longer, he would’ve gotten the kind of acclaim he wanted—but I think because he grew up deprived and in need of money, he was afraid to let up the brakes, afraid to stop writing these paperback westerns, afraid to truly push for hardcover publication, and for that reason his literary aspirations were delayed too long for them to truly bear fruit.

But I admire his education, his work ethic, and (some of) his books. I also think his accomplishment—connecting with readers who don’t normally read many books—is extremely impressive. You’ve got all these guys on Substack writing about how men don’t read books—well, once upon a time, men read Louis L’Amour. Regular guys. Admittedly, they were oftentimes these ranch hands and cowboys and truck-drivers, who worked in remote places and didn’t necessarily have access to TV (which they likely would’ve preferred). But so what—that just meant L’Amour offered them exactly what they needed.

Is it my duty to hate bestsellers?

With L’Amour, I find it hard to give him my thorough-going recommendation, but there are plenty of other no-brow or low-brow or middle-brow writers I’ve recommended enthusiastically on this blog: O. Henry, James Fenimore Cooper, Robert E. Howard, and many more.

Sometimes I wonder if this is a good thing to do. I often think perhaps I have some duty to spend more time defending the established canons of literary taste.

It does feel like a lot of our problems, as a literary culture, come from people trying to be cool and go against the received wisdom. This leads to short-term gains—it allows you to stand out against the crowd—but in the long term it erodes peoples’ faith in the critical consensus.

However the classics are nothing more than received wisdom. They’re just books we’ve been told were good. I do my best to err on the side of trusting this wisdom. That’s why I was reluctant to recommend Edna Ferber, for instance—because there’s another author, Willa Cather, who wrote similar stuff, but is held in much higher regard.

However, I also like to situate each author in their context. Edgar Allan Poe is great when you’re reading “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “Cask of Amontillado” in 8th grade, but it’s not necessarily worth reading his collected stories for fun. Louis L’Amour was probably great if you a ranch-hand browsing the paperback spindles at a railroad station in 1975, but is less good if you’re a looking for a diverting read in 2025.

Similarly, a lot of the angst over the relative popularity of various genres of contemporary fiction would disappear if we paid more attention to how they are consumed. For instance, I have read dozens upon dozens of domestic thrillers (”Girl On A Train In The Lake By The Window” stuff), but I listened to most of these books while I was grinding Diablo 3 on my computer. I enjoyed them immensely, but I don’t play Diablo 3 (or any games) anymore, so don’t often read them. Similarly, if my book club was somehow to disband, I would likely read many fewer books like Flesh. I am not reading domestic thrillers instead of literary fiction, or vice versa—the two genres have completely separate places in my life.

I do believe that the best books transcend their origins. Philip K. Dick and Ursula Le Guin were originally published on those very same paperback racks, right next to the rack holding Louis L’Amour—but now they’re published in Library of America editions. Similarly, many contemporaries read Moby-Dick because they really wanted to know more about whales and whaling—they read it sort of like a middlebrow novel, it was educational and entertaining. Nowadays we don’t necessarily care how many buckets of sperm you can get from the head of a whale—we read the book for substantively different reasons.

I think Flesh is a good book

With a book like Flesh, I cannot say whether it’ll transcend its origins as a buzzy literary book that’s intended to be read by a certain sort of upper-middle-class consumer who is anxious to keep current with literature. These books are also a product, and after five or ten or fifteen years, most of these books are forgotten.

All I can say is that I enjoyed Flesh quite a bit. The problem that Szalay faced was the same problem many writers have dealt with, which is that many people aren’t particularly introspective. They don’t have the kind of interior life that is capable of bearing a novel’s worth of scrutiny. They behave in ways that are a mystery both to themselves and to others. It’s not that they don’t have desires, but they don’t necessarily feel those desires in a conscious way, and they are often surprised by the nature of those desires.

In Flesh, Szalay does a great job of conveying that this is a protagonist with many passions, and that those passions often burst out of this protagonist in unexpected ways, but that the narrator doesn’t necessarily verbalize those passions, even to himself. The best parts of the book, for me, were the points where the narrator would act, and, in the process of acting, he would finally be able to experience whatever he’d been feeling. Here’s an example:

He likes lying there naked while she touches him.

The rest of the day feels somehow fake compared to this. It feels like a less intense sort of reality. It feels unimportant.

The important part of life happens with her. That’s how it feels.

It’s a great performance, and I learned a lot from it. I recommend the book.

Generally speaking, I don’t enjoy books like Flesh, which have been published to much acclaim and have won prizes, but in this case I did. If they were all this good, the literary world would be a much healthier place.

Flesh may not be a classic

I think there is a perception that books like Flesh, written by authors who aspire to literary quality and published as high-quality books, have some advantage when it comes to being perceived as classics by future generations. But I don’t know if that’s actually true. It seems to me that when we look at the twentieth century, there are many award-winning writers, highly-acclaimed in their day, who’ve been forgotten (Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, Thomas Wolfe, Tom Wolfe, Booth Tarkington) and many commercial fiction authors who are remembered (H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Philip K. Dick. Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler).

As I mentioned in an essay last year, the Hugo Award For Best Science Fiction Novel seems to do a much better job of predicting a novel’s longevity than does the Pulitzer Prize For Fiction. And it’s clear that the difference between commercial fiction and literary fiction is not always a function of education or aspiration. Louis L’Amour aspired to write great fiction, and he educated himself by reading the classics—he viewed his own work as being in the tradition of the great novels of the past. History has, by and large, not agreed with him on that score, but in this it’s rendered no worse a judgement on him than it has on Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal and hundreds of other authors who were critically acclaimed in their own day.

I’m sad not to recommend L’Amour more wholeheartedly. I spent a month with his work, and I developed a strong relationship with his voice. Even in the less-distinguished of his novels, there was a solidity, an integrity, that I really enjoyed. I felt like I couldn’t leave the Western behind without understanding the world’s most popular writer of Westerns, and I am happy with the understanding I’ve gained—hopefully to some extent I’ve been able to transmit that understanding to you, even if I can’t recommend that you go out and read the books yourself.

Except for The Education of a Wandering Man—that book is seriously good.

P.S. Woman of Letters will be on hiatus until after Thanksgiving. See you December 2nd!

The Literary Reputation Poll

Nine hundred people have taken the Literary Reputation Poll—my attempt to figure out which classic authors you all are actually reading. If you haven’t taken it, there’s still a little time left to be counted, but the poll closes December 8th!

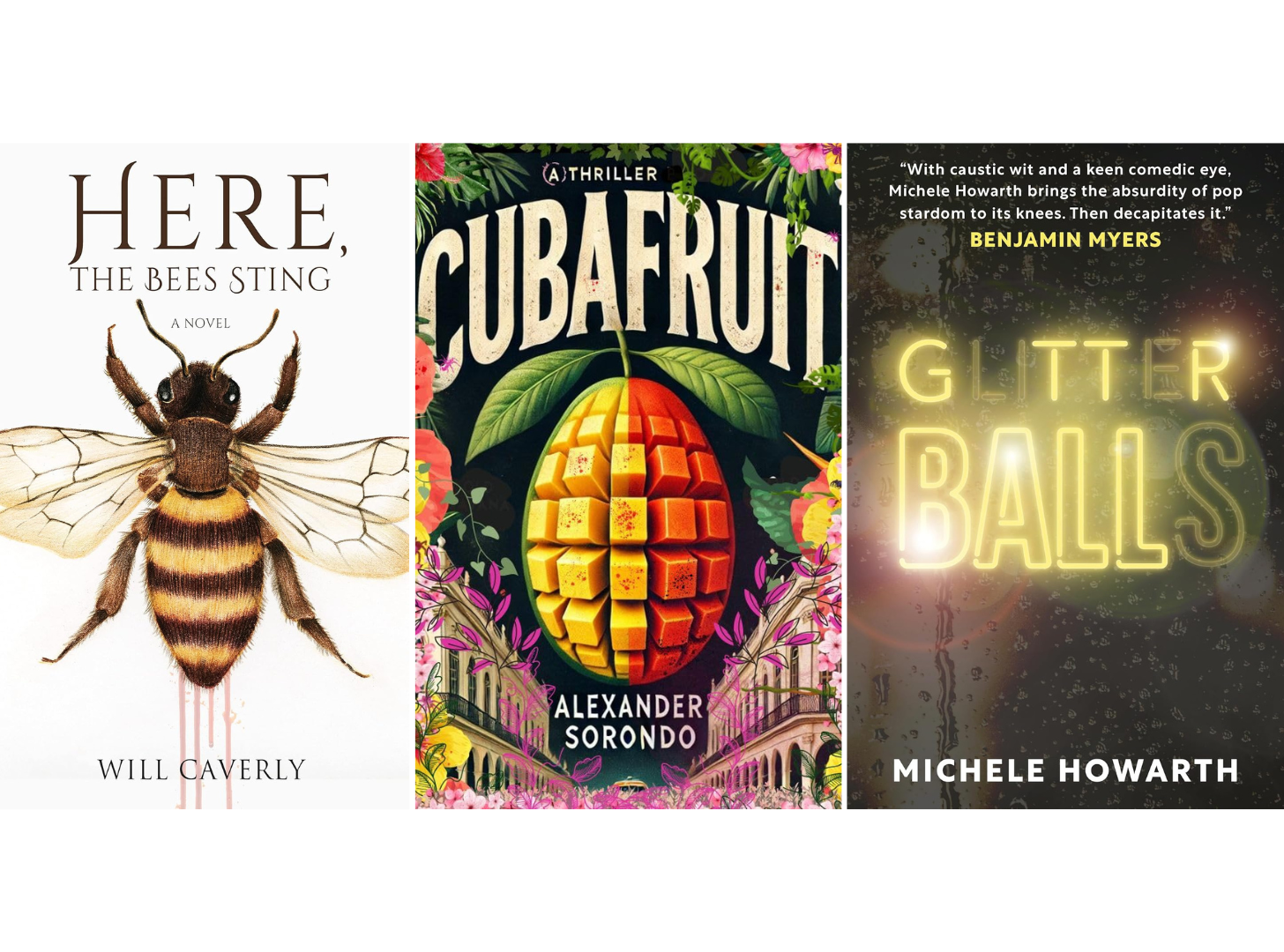

Four out of ten Samuel Richardson Award finalists have been announced!

Thank you very much to our judges Moo Cat, Abra McAndrew, and T. Benjamin Whitefor their work in our effort to find the best self-published literary novel. Each judge selected one finalist from their pile:

Moo Cat picked Michele Howarth’s Glitterballs:

Glitterballs deserves more attention than 6 reviews on Goodreads. Howarth is a talented writer, and she easily rose to the top of my pile of novels for the Samuel Richardson Award from the first paragraph of the introduction

Abra McAndrew picked Alexander Sorondo’s Cubafruit:

The book weaves a minute-by-minute unfolding of that drama with multiple 20th century timelines in an alternative history of Cuba, constructing a web of political violence. At its heart is the uneasy triangle between the people who make history, the people who try to survive it, and the people who live to tell about it.

T. Benjamin White picked Will Caverly’s Here, The Bees Sting:

This is tense and well-plotted, real edge-of-your-seat writing. Caverly could put out more thrillers, and I’d read them. But Caverly’s real literary skill comes through a clever twist: Billy’s story, it turns out, is only about 70% of the book. The other 30% follows a parallel narrative, taking place inside a bee hive and starring the bees themselves.

And I picked Merritt Graves’s Drive A.

Drive A is a deeply-humane book, and no matter how weird the story gets, the people never stop feeling like real human beings. Cable is better than most of his coworkers, but he’s not so much better that he feels like a sheep amongst vipers. What makes the story so compelling is that you can see how true happiness, true friendship, true love, and even true job satisfaction remain tantalizingly possible in the midst of this zany, dystopian world.

All of these books are currently available online, and if any of you gives one of them a review (positive or negative), I’d be happy to link to it here.

The rest of the finalists should be announced by the end of 2025, and then the judges will spend the next few debating who should win!

Books Consulted For This Post

L’Amour, Louis – Conagher (1969)

L’Amour, Louis – Flint (1960)

L’Amour, Louis – The Sackett Brand (1965)

L’Amour, Louis – Education of a Wandering Man (1989)

L’Amour, Louis – The Lonesome Gods (1983)

L’Amour, Louis – Bendigo Shafter (1979)4

L’Amour, Louis – Last of the Breed (1986)

L’Amour, Louis – Sackett’s Land (1974)

L’Amour, Louis – The Iron Marshal (1979)

L’Amour, Louis – The Daybreakers (1960)

L’Amour, Louis – Hondo (1953)

L’Amour, Louis – The Walking Drum (1984)

L’Amour, Louis – The Key-Lock Man (1965)

L’Amour, Louis – Comstock Lode (1981)6

Phillips, Robert – Louis L’Amour: His Life and Trails (1989)

Szalay, David – Flesh (2025)

Sutherland, John – Bestsellers: A Very Short Introduction (2007)7

On the other hand, those two also recommended Solvej Balle’s On The Calculation of Volume. I read the first book last year and found it to be intensely boring.

I reread all of Adichie’s books in order to do that review, I came away with much more respect for Americanah in particular. That’s a really good book! It has so much life.

“A rumor was circulated that somehow Louis was a creation of his publisher, Bantam Books, and that they told him what to write and then gave him preferential treatment over other writers when it came to money and advertising. In truth, Louis wrote in a manner that was very much like stream of consciousness and it was nearly impossible for him to plan what was going to happen in one of his books let alone take direction from someone else.” (Source)

Bendigo Shafter is one of L’Amour’s best. A group of pioneers decide they can’t complete the trail west, to Oregon, so they decide to stop in Montana, where they found a little town that faces various troubles. It’s a relatively small-scale, slice of life story, and a coming-of-age tale for the protagonist, Bendigo Shafter, who starts the story as a young man, and slowly turns into an eminence and a leader.

Fallon is one of the most entertaining of L’Amour’s novels. It’s about a card-player who is running from a lynching posse out for his blood. He runs across a wagon-train of pioneers and convinces them that a nearby ghost town actually has silver. He intends to build up a town and sell its nonexistent silver mines to some investors, to gain a stake that’ll led him head west. But his lie takes on a life of his own, and he starts feeling responsible for this poor town.

Comstock Lode was also pretty good, although it has some frustrating aspects that stop it from rising to the level of Bendigo Shafter. At its core, this book is about the crazy boomtown atmosphere in Virginia City, Nevada, during the silver rush—the same atmosphere chronicled by Mark Twain in Roughing It, the best of his travel books. But the plot is marred by the protagonist’s obsession with getting revenge on the people who killed his dad—this revenge plot so dominates his psyche that you don’t get enough of the great silver-mining stuff.

I’ve read a lot of Very Short Introductions, and this one is one of the most entertaining and spritely. I learned a lot about the history of the bestseller and various genres thereof.

Gore Vidal was a little weird though! He didn't really win literary awards, unlike Mailer, who won many, many awards. Vidal was an NBA finalist for Burr but that was about it. If anything, critics tended to sniff at his fiction because it was historical fiction - too genre - OR because it was *too* transgressive. The guy wrote the great gay novel in 1948 and the great trans novel in the late 1960s. He was too much, too soon for a lot of critics. His great gay novel, The City and the Pillar, got him blacklisted for a decade effectively.

You need to go down a Gore Vidal rabbit hole soon. You won't be disappointed.

Guess I'm going to read Louis L'Amour's memoir now. I love this post, and appreciate the work you put in because I saw his books all over the place growing up, and never read one or read anything about them before. (Yet, so much about Flowers in the Attic)