Why I am publishing a novella on Substack

I recently attended the Tamara de Lempicka exhibition at the De Young.1

When I visit a museum (which admittedly is perhaps once a year), I like to go through the exhibit a few times, scope it out, then go back to the beginning and spend a few hours looking at just a few of the paintings.

In this case, some of the paintings were clearly more important than the rest. One of them is the painting from all the exhibit materials (the coffee table book, for instance). But there were a few other paintings that were also noticeably more important than the rest. You could tell because they were set apart, often alone on a wall.

And you could also basically tell from the placement of the chairs which paintings were most important—there were always chairs in the vicinity of the important paintings, but either the angle wasn't great or the distance wasn't close. Museums want people to sit and look at these paintings, but they don't want the sitters to be too close, so they block everyone else's view. Anyway, I sat in those chairs, and I looked at the important paintings.2

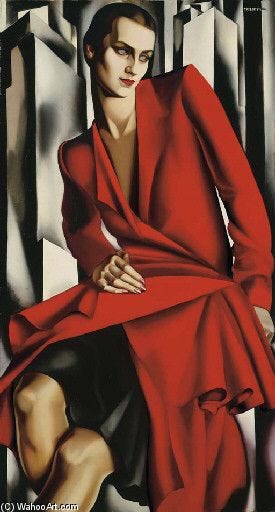

They were beautiful! They were so awe-inspiring! One in particular—this woman in a red suit—I just felt so safe with this painting. I was like, this painter put everything into this painting. This painting is exactly what they wanted it to be.

Lempicka's most famous paintings all have this style. They have a glossy look, very smooth surfaces, you don't feel as if you're looking at paint at all. And they're usually paintings of young women with small, pointy breasts.

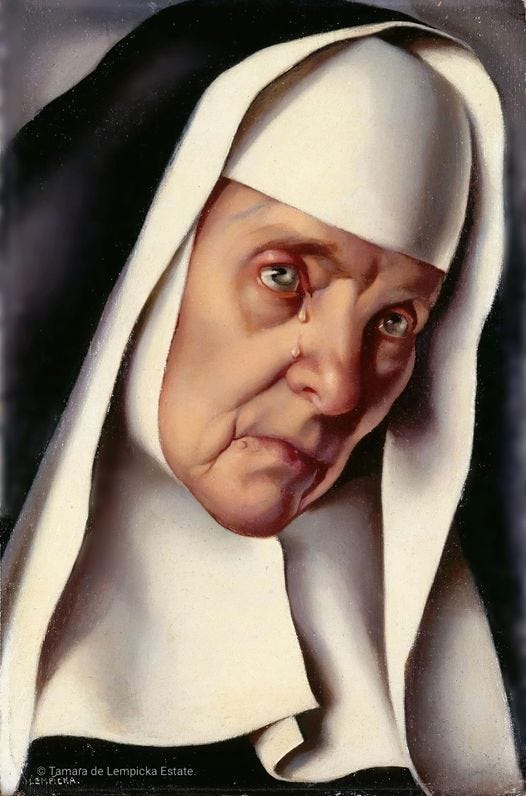

I'm sure she could've painted in this style for her whole life, and people would've loved it. But at the tail end of the thirties, she stopped. She painted a few paintings with religious themes, and she showed them in 1941, but people really weren't into them. Understandably so—they were distinctly different from her more-famous paintings, and, to my eyes, much worse.

After that, she more or less stopped painting. She lived until 1980! But she didn't paint much in the latter half of her life. I honestly think...she just didn't have it anymore. Like, when she first broke out as a painter in the 1920s and 1930s, she really believed in this vision of speed and glamour and danger. She believed in youth! And that it was good to look at young women with pointy breasts!

After a while, she maybe didn't believe that anymore. But...she didn't know what else to paint. I could be wrong about her having painter’s block, but what's clear is that in the latter half of her life, she did not have a body of work that she felt strongly about showing to the world.

I understand this completely. It takes a lot of effort to put your creative work into a form that’s suitable for other people to interact with. Right now, I am in the process, with my Thursday tales, of working out a new style—and I've produced in these three months a number of short stories that I am very proud of. But...these stories will disappear unless I someday collect them into a book that can, hopefully, survive the collapse of this platform.

Putting together a book of these rather odd stories—that would be work. I would need to commit to that work. I'd need to convince my agent that this book ought to exist. I'd need to convince my last publisher, Feminist Press, that these tales are important—or, failing that, I'd need to find a new publisher.

Writing a book is simple; getting that book published is much harder and much more emotionally taxing. At the moment, I am reading a fantastic novel, The Last Samurai, by Helen DeWitt. It is one of the best books I have ever read! I don't have time to describe it now (and anyway I am not finished reading). But this book is the book! It resembles Infinite Jest in that the book is overtly brainy and the subject is a precocious child, but The Last Samurai is so much better than Infinite Jest, because it's much more coherent story-wise and a lot less nihilistic.3

DeWitt had a lot of difficulty with her publisher while putting out this book. It's a strange book, with lots of different alphabets and typographical quirks. She had to go to war with her publisher to get everything in a readable shape. Since then, she has written other work—I read her recent novella, plus a story collection of hers, both of which were excellent. But I get the impression that she is hesitant about committing fully to another novel, precisely because she knows that any Helen DeWitt book is going to require a lot of effort to put into the world properly.4

It's very easy to say, oh just write whatever you like and attention will come when you're ready, etc. That is all true! You do have to write without thinking about the future. That is what I am doing on this Substack.

But...you also need to find ways of presenting your work in a good light. Otherwise people won't read it. They'll think, hey...this author doesn't believe in it, so why should I?

The museum did a great job of presenting the Lempicka exhibition, but its other exhibits showed much less care.

After going to the Lempicka exhibit, I went upstairs, where they had another special exhibit, of these Italian tapestries from the Renaissance. They were great, but I didn't feel like committing to them right now—If I return to see Lempicka again, I might spend more time with the tapestries too.

However, the rest of the upstairs exhibits seemed very diffuse, and as a result it was difficult to appreciate the art on display. This is often true of secondary exhibits, but in this case it felt particularly true. Like, when I went to the Legion of Honor last year, I felt cared-for: the permanent exhibits were very thoughtfully arranged, lots of artists I've heard of, beautiful pictures.

In contrast, the De Young contains a space on the ground floor that just...appears to be an empty room! I wandered around this room being like...what am I looking at? Why is there an empty room here? It turns out that the room contained murals that'd been at the old San Francisco Main Library—they had to be moved when that library got turned into the Asian Art Museum.

Ultimately it felt like...the Asian Art Museum didn't want these murals, so...we just put them here in this empty room!5 But the room still felt empty! Because the murals were a bit faded (or maybe they were supposed to look that way, I have no idea!) So they looked like wallpaper or the sort of neutral art you might put in a hotel hallway.

Are these murals actually good? Are they actually worth my time? I imagine that they are not! But they're taking up a whole room in a museum! If they're no good, something else should be here. And if they are good, then please tell me they are good!

This was an egregious example, but it's the vibe I got from the whole upstairs. There are three semi-permanent collections upstairs, for American, African, and Oceanic art. The African and Oceanic collections suffered from the same problem, which is...Africa and Oceania are quite big places! Unless you're careful, it's easy to just look like you're showing a bunch of disparate objects with no connection other than that they came from this region. And the danger there is the viewer starts to wonder: "Was there any care shown here? Which of these objects are actually good?"

I could go into more detail, but if you've ever been in a museum I think you fully understand the hodge-podge of objects I'm talking about.

Personally I hope that I never give off that perfunctory vibe in talking about anything that I think is worthy of your attention. Almost every book I talk about on my blog is a book that I have read! If I haven't read it, I say so. If I skimmed it, I say that too. If it's worthy of your time, I say that as well. That's my credibility at stake. This museum's credibility is damaged by the perfunctory treatment of some of its art.

But the Lempicka exhibit was quite good! And the point of the De Young is basically to have a place in SF for these traveling exhibitions, so...I probably shouldn't be too hard on it. Like, these special exhibitions are where they’re putting their time and effort, and it shows. But I do think they should at least put a bigger plaque in the empty room.

Money Matters

In two days, I will be sending you a novella called Money Matters. It is fifteen thousand words long. The email will be cut off in most of your email clients. If you're interested in reading it, you should probably click through and read it on the Substack site itself or in the Substack app.

I expect that most of you won’t finish reading it, and that’s fine. I’ve recently gotten about a hundred new subscribers because Henry Oliver released a podcast interview with me—those people signed up because I am interested in the Great Books. They don’t necessarily want to read my fiction.

Moreover, fifteen thousand words is quite long for an email. I mean, many New Yorker articles are that length and it should take no more than an hour and a half to read, but still…it’s quite long. A reader could be forgiven for thinking that this choice of format means I do not believe in the novella. Certainly I could've chosen to send it out as three separate emails, on three separate weeks, but I worried this would tax peoples' patience.

Sending out longer stories to my Substack is very much still an idea I’m still testing out. I think that’s why you can sense a certain hesitancy about my whole presentation. The thing is, when you’re a fiction writer, there’s a feedback loop between composition and publication. It’s very hard to write unless you see a place on bookshelves for the work. With literary fiction—I know it appears like the market is strong because there’s so many books coming out all the time and there’s so many journals, so much much ferment and discussion. But in practice, and I do not expect you to believe me about this, it is very, very hard to get anyone interested in high-brow fiction. You need so much social proof, in terms of awards and fellowships and whatnot, before anyone will pay you the slightest attention. It’s quite exhausting even to think about.

And that’s true even when the stories are, like mine, relatively accessible!

It’s just very hard to stand out, hard to make the case to agents and editors and critics that your work is important and is worth their time. And the effort it takes to stand out—this effort often gets in the way of actually writing work you believe in.

I do think Money Matters is very good. If I ever put together a book, this novella will likely be a centerpiece of that book. I’ve developed a certain style recently that’s both personable and flexible—it’s a voice that’s very capable of spanning time, space, and genre, often within the space of a single piece. A voice that’s highly influenced by my reading of the Great Books and, in particular, by pre-modern works of fiction (especially Chaucer, Boccaccio, and the Icelandic sagas).

This novella also forms a complement to my criticism. For the past few months I've basically been asking the question, "Is this it?" Repeatedly, I have said that fiction needs to do more than simply present the meaninglessness and difficulty of modern life. I want more. I want an answer. There are many answers that exist! God is an answer. Art is another one. Bourgeois family life is a third answer.

I understand that artists cannot simply pick an answer—it must be an answer that they genuinely believe. But if an artist does not believe in anything—if they truly feel there is no escape from life's meaninglessness—then, while that is a terrible conundrum for them, I don't know that their confusion is worthy of my time.

Personally, I do have answers. People might not agree with those answers, but I do have them. At some point I might stop believing in those answers, and at that point I'll likely lapse into silence like Tamara de Lempicka. But right now, for this moment. I do have something. And I think you'll find that thing in my novella, Money Matters, which you will all be able to read in two days.

Here is a link to the exhibit. I’m going to start taking a page from Chris Jesu Lee and putting the links at the end of the piece, instead of scattered throughout.

I tried to be mindful that there could be people with mobility issues who wanted these chairs—there was plentiful seating, most of which went unused, given that it was a Tuesday morning. And at a certain point, maybe I myself am the one with the mobility issues. After all, I cannot really stand comfortably for hours on end. Just wanted to put this note in here so people didn’t think I was a total boor.

Needless to say, I love David Foster Wallace, and I highly recommend Infinite Jest, but it is clearly the book of a man who didn’t quite know what he was doing.

Another novel, Lightning Rods, did eventually come out. This novel was trapped in limbo for years due to publishing industry shenanigans. Much of her output after The Last Samurai is basically about how traumatized she feels by the publishing industry, and I think she feels very robbed of her ability to write. As DeWitt puts it:

I explain to people that if they want books like Samurai, which they all say they do, I can’t be asked to engage in intellectual prostitution; I point out that I have about two hundred unfinished books on my hard drive, so there is money to be made from letting me do it my way…I tell people what I can’t deal with; I put clauses in my contracts and I explain: this clause stands between me and suicide, don’t sign this contract if you are not going to comply with it—and they laugh.

I owe a shout-out by the way to Celine Nguyen, who encouraged me to read DeWitt. All of Dewitt’s work is incredible—reading her bitter post-Samurai work has been very cathartic for me, personally, but The Last Samurai is truly a work of genius. The only thing marring my experience of the book is how inadequate it makes me feel!

Here is the background story: The Asian Art Museum basically paid the De Young to take these murals.

I just wanted to share this song from the musical Lempicka. It's got to be one of the greatest songs about the human at the heart of the creative process.

https://open.spotify.com/track/3Nse8DZcXWKUo1sb6yjDlL?si=58e26a11608a4177

What are the chances? I walked into Pasticceria Piccioli in Florence today and saw two Lempickas on the wall.