When you're a published writer, reading becomes less rewarding

I read many Substacks these days. I enjoy many Substacks. Usually I am drawn to a writer because of their unique worldview, which is inflected by their knowledge and life experience. One writer knows a lot about design thinking; another writer knows a lot about Neo-Keynesian economics; another writer is always referencing the Lake poets. When I first encounter their work, each of these writers seems so vital and alive, so full of passion.

But over the course of several months, I realize that their references never change or evolve. It's always design thinking. It's always Neo-Keynesian economics. It's always the Lake poets.

And I see something else: whenever they discuss a recently-read or recently-watched work of art, it's almost always a work of pop culture. Quite frequently it's a movie. Sometimes it's a pop star. On occasion it's a book, but almost always a trendy, much-talked-about novel or memoir. Their current entertainment choices seem startlingly disconnected from their former ones. They are someone who once loved and explored the Lake poets, and that person is fossilized inside of them, so they are still able to summon that enthusiasm and insight whenever they'd like. But it's a dead enthusiasm: they are no longer the kind of person who can form new interests.

For many of these writers, it is genuinely impossible to imagine them sitting down and reading a book. I find this is particularly true for many of the center-right literary critics, of the sort who write for, say, Compact or The Spectator. They are clearly well-read and erudite, but their approach never evolves. They are making the same jokes and the same references they might've made thirty years ago. They’re like LLMs trained on an ancient dataset: whether it's trans rights or Taylor Swift, their references will always be to the Protagoras and to The City of God and Milton and Donne and whoever else they were reading in their twenties and thirties. Their writing is still brilliant and insightful, because it's genuinely fun to see what some crusty neo-con thinks about, say, BDSM or psilocybin mushrooms. The writing isn't bad--it's only in the context of a weekly newsletter or newspaper column that their lack of evolution starts to seem genuinely troubling. Over time, you realize that this fascinating person, who read Classics at Oxford and infiltrated communist Hungary for MI-6 and worked for ten years as a theater critic, has become intellectually inert. They probably still read books, but only sparingly--for perhaps a few hours a week, if that--and they quite frequently put down books a fourth or a third of the way through (“It's just one of those kinds of books, and I already know what those kinds of books are like”), and it is rare in the extreme for a book to send them in a new direction or spark in them a desire for more investigation or, god forbid, cause them to actually change their mind.

Of course nothing is more common than for a person to be close-minded, but what I find depressing in the extreme is that this person clearly had intellectual curiosity at some point. Indeed, the fossilized remains of that intellectual curiosity are apparent in virtually everything they write: it would not be an exaggeration to say that the only reason they have a career at all is that once upon a time, they were an unusually curious person.

So what changed?

Every writer finds themselves launched upon their public career with some fund of knowledge--the product of their childhood curiosities, college enthusiasms, professional training, and various abortive creative projects. The moment the writer sells a book or achieves a regular readership, this naive accumulation of knowledge is ended. It is not that reading for pleasure or edification is goes away entirely--what happens instead is that their reading life becomes subjected to a sort of passive discipline. Fiction writers read the books of their friends, they read books for blurbing, and they read whatever books are being heavily discussed by their community. Nonfiction writers read other columnists, they read books for review, they read periodicals, they read to research ongoing projects, and they read whatever is enthusiastically recommended to them by others in their community.

This form of semi-professional reading bears little resemblance to the kind of reading the writer did when they were unknown or unsuccessful. Back then, they almost never had any immediate careerist aim when reading a book. If they picked up a popular book, it was because they were curious, not because they needed to "keep up with the discourse." Which is not to say that their naive reading was without any ulterior motive--almost always, there was an element of ambition that determined what they read. But it tended to be a creative, rather than professional, ambition. When the writer is still striving, they put much stock in improving themselves, and they pick books they think likely to effect that improvement.

Slowly that creative ambition ebbs. To some extent this is a product of self-defense. A writer who's already launched in their career needs to maintain their own confidence that their work is worthy of attention, but creative ambition tends to undermine this confidence. After all, if the writer needs to improve, then doesn't that mean, by definition, that their current writing is deficient? Of course no writer will ever admit that they're done improving. Every writer will claim they are striving to better themselves, but published writers almost inevitably lose their beginner's mind--their willingness to put everything on the table, to question everything about their skills and their aims. Instead, published writers tend to improve incrementally. They have a few areas where they want to innovate: a few things they dislike in their writing or a few new areas they'd like to explore. They want to improve, but they don't want to undermine what they already know. And yet this unwillingness to call into question your own accomplishments is exactly what leads to creative ruts and a diminishing of creative ambition.

Over time, as more and more of you reading becomes infected by careerism--the sense that you are reading not just to improve yourself but also to materially improve your career as a writer--this reading becomes somewhat rote. You pick up a much-hyped book and you already know what type of book it is and what to think about it. Perhaps the writer reads the book anyway, but whether they read it or not is immaterial: their reading experience almost always conforms to their pre-existing expectations.

Most, perhaps 80 percent, of a published writer's reading life tends to be in service to these prejudices and external aims.

With the disappearance of creative ambition, what is left is reading for pleasure. To some degree, a writer is still able to read the books that they enjoyed reading before they became a writer. A writer might find themselves increasingly drawn to mysteries or to crime novels or to presidential biographies. In other words, they are still able to read like the average member of their social class. And since these books are the only books that the approach without expectation and, increasingly, the only books that they genuinely enjoy, these books tend to form a larger and larger part of their intellectual life. That is why, for instance, so many literary critics seem to devote an increasing amount of their time, as their career progresses, to popular culture, whether it is movies, television, music, or genre fiction. It's because popular culture is the only part of their reading or watching life that still seems vital and interesting, because it's the only thing they're able to approach with any kind of generosity--paradoxically, because they expect so little of it, they can only recover their beginner's mind when they, say, watch reality TV or read a Jenna's Book Club pick.

Personally, the exigencies of writing a twice-weekly newsletter have made me realize how difficult it is to genuinely find the space and time to read something new. When you've become an established writer, it's easy to write. I wrote this blog post in about a half hour. Writing is quite pleasurable, and it's simple to ignore distractions. For the first ten years of my writing life, I turned off the interne whenever I wrote. I no longer bother doing that, because I find that writing is more fun nowadays than browsing the internet!

But reading books has gotten increasingly more difficult and time-consuming. I've spent ninety minutes today reading The Making of the English Working Class, and I've gotten through about a chapter. According to my e-reader I've spent ten hours reading this book over the last ten days, and I'm still only half-way through it! Reading is like exercising. If you skip a day or a week or a month, you won't suddenly become depressed and out of shape, but over time you'll get flabby, and everything you do will be that much harder (I don't exercise at all, by the way).

But when you're a working writer, it becomes harder and harder to read in the way you ought to. Before you're published, writing is painful and dangerous--every piece is just an invitation for rejection. Reading, in contrast, is safe and exciting: if you can read Tolstoy, you can imagine someday writing like him. Reading is a shortcut to the sort of creative and professional fulfillment we're not able to get with our writing.

But after you've started getting published, it's the opposite. Every word you write is a chance for money and applause, while reading feels curiously inert and unheralded. When I read--especially when I read something new or difficult--I can feel like a rude. Aren't I better than this? I've got five books under contract, and yet I'm still struggling through this book exactly the same as any undergrad might! A difficult book becomes, in some sense, an affront to the working writer's dignity.

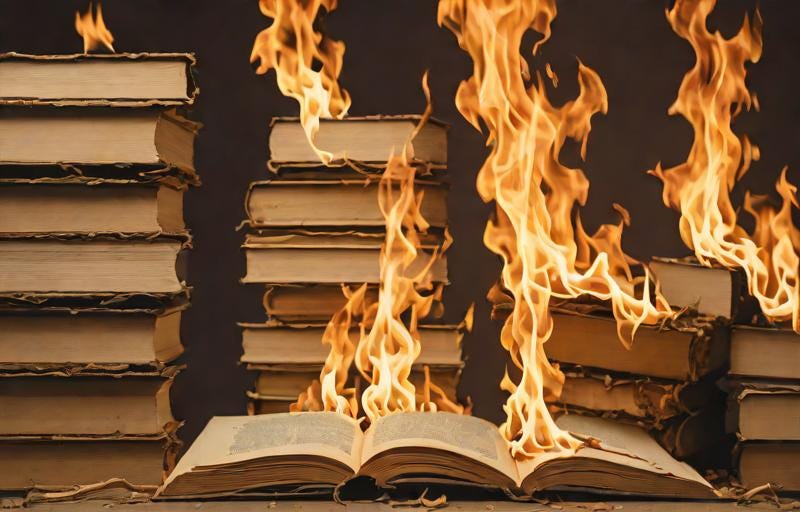

You don't need me to close this post with some peroration about how reading is important. We know it is. We know reading is critical, not just to improve one's abilities as a writer, but to maintain one's self-respect. No writer can long avoid feeling like a fraud if they cut themselves off from the wellspring of literature: over time the writer who's stopped reading (or stopped reading generously) becomes bitter, angry, and stagnant.

We all know this. And yet knowing it doesn't get the reading done. I still need to find the time every single day to ignore my emails, ignore my chores, ignore my child and dog and wife, and crack open a book. And many days, too many days, I fail.

I’m reminded of the old adage—a writer spends their entire life writing their first book, and then spends a few years writing every other book they will ever write. Once you start writing as a career, the demands of having to churn out writing pressures you to think and reflect less and crystallize your opinion more: you spend more time writing than reading, and you read only to write about it instead of reading to change your perspective.

Another idea: smaller writers aren’t penalized for writing outlandish pieces, because no one sees their smaller failures. This allows them to take more risks and be more varied. Established writers have a reputation to defend, and thus are more likely to write what they know. Even worse, what happens if you read and change your mind and then suddenly disagree with one of your books? That seems pretty risky—and writers probably want to avoid the cognitive dissonance that comes with disagreeing with and old published book.

I’m reminded of the old adage—a writer spends their entire life writing their first book, and then spends a few years writing every other book they will ever write.

Another idea: smaller writers aren’t penalized for writing outlandish pieces, because no one sees their smaller failures. This allows them to take more risks and be more varied. Established writers have a reputation to defend, and thus are more likely to write what they know.

(Full transparency, I think both of these ideas stem from Astral Codex Ten—I vaguely remember Scott witting a post about why he fell off ot something?)