We must re-learn how to be good courtiers

On the Great Books and achieving power (and also some Tang Dynasty poetry)

Once upon a time, I wrote an essay about how nobody cares whether or not I've read Plato. But I'm starting to realize that's no longer true. For the first time in perhaps a hundred years, knowledge of the Great Books has become a pathway to power.

This is most true amongst the right-wing, where the classic example is Bronze Age Pervert--who's achieved fame precisely because he's reconfigured Plato as a supporter of tyranny.

In a similar way, it would be extremely easy to turn Plato and Aristotle into supporters of left-wing illiberalism, particularly in the arts. Neither of them had more than an instrumental value for the arts, and they certainly wouldn't support any arts that undermined the state. But nobody's done it, why? It's because woke people don't read Plato and Aristotle.

And that’s a gap that’s waiting to be filled.

What I've realized is that elites value high culture. Elite parents complain that their kids aren't learning classic books, both because parents are inherently conservative, but also because these parents value knowledge they can touch and feel and understand. In the realm of the humanities, knowledge of the Great Books is as close as you can come to a gold coin--it will always retain its value, no matter what.

I’ve come to realize that the reaction against high culture by certain parts of the elite is nothing more than shame. It's a body of knowledge they don't have, so they denigrate it. This is why reaction against the Great Books is fiercest amongst people who study the humanities, because that's the realm where disputes about bodies of knowledge turn into professional disputes. If the job goes to a Milton specialist that means it's not going to some other specialist.

But while those intramural disputes shape the response to the Great Books in the journals and newspapers, they don't affect how they're viewed in the popular imagination. And the reason, quite frankly, is nationalism. The Great Books are viewed as symbols of our own greatness as a society. Even the stock we put in the Great Books of other cultures tends to wax and wane in direct relationship to those cultures' relative power. For instance, we see over and over in non-Western countries that their interest in European books increases dramatically in the 19th and 20th century. Suddenly Arab thinkers were very interested into the Enlightenment. Was there anything stopping them from reading Descartes in 1700? No, but in 1700 it didn't seem nearly as pressing as it did in 1900. The same thing happened in China after the century of dishonor, and in Japan after their humiliation by Commodore Perry.

Because of our own cultural chauvinism, the Great Books are never going to lose that totemic value for Westerners, no matter how poorly-studied or denigrated they become.

Of course now we're getting in Treason of the Clerks territory. Because the last time high culture was pressed into the national project was, of course during the rise of nationalism, in the period from 1870 to 1930—a phenomenon gave rise to Julien Benda's classic polemic on how intellectuals were betraying high culture by linking it to explicit political projects. His most famous line is: "humanity did evil for two thousand years, but honored good. This contradiction was an honor to the human species, and formed the rift whereby civilization slipped into the world."

The duty of the intellectual isn't to support some person or peoples' quest for temporal power, it's to further human civilization as a whole.

That's the contradiction that Strauss develops in Natural Right and History. The true philosopher doesn't want to rule; they just want to do philosophy. That's why rule should be conducted by gentlemen, people who have been formed by philosophy, but who don’t pursue first-order knowledge themselves.

It's universally acknowledged that today we lack gentlemen, but our lack of gentility is also felt by the erstwhile ruling class! That is precisely why at this moment in history it is possible for outsiders to slip into power through the use of high culture. In a generation or two it won't be doable, because the genteel class will have mastered a body of cultural knowledge that they feel comfortable claiming as their birthright, and it won't be possible (except with extreme difficulty) for an outsider fake something that the gentle-people have had since birth. In other words, right now, at this moment, the children of meritocrats and oligarchs are being educated like meritocrats and oligarchs. But in a generation, they’ll be educated like gentlemen and gentlewomen and gentle-nonbinary-individuals.

I mention all this because I've been thinking about the purpose of this blog. I initially intended to devote it to private knowledge. The title "woman of letters" signals my intention to disclaim any "public intellectual" mantle and to avoid holding forth on current affairs. To the extent that I have political opinions, they are a result, not of my cultural knowledge, but of my socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. To put my cultural knowledge in the service of those opinions would be a travesty, as it would imply that reading these books had in some way shaped my views about how the world ought to be run, and that's simply not true. There is likely not an iota of difference between my politics and that of everyone else who lives on my street in San Francisco.

But, in thinking about what I was capable of doing, I think it would also be a lie to say that I came to the Great Books seeking only private knowledge (another working title for this blog was "private intellectual"). I came to them, quite frankly, out of ambition, because I assumed that writing well required reading the best of what'd been written.

I still think that. I don't think that I can give you any knowledge that will help you succeed in the world. But I do think you can gain that knowledge from these books. I am not saying that “books” or “literature” are important, in an abstract or aggregate sense. What I am saying is that reading the best works of philosophical and imaginative literature can aid a person whose aim is to achieve great things. I see you not as a member of the demos--destined only to play a role in the world as a citizen--but as a potential member of the best, the aristoi.

This is, I think, different from the Bloomian or Straussian project of arguing that the aristoi ought to lead or ought to rule. I have no opinions about who ought to be in charge. I merely think that if you want to be the best, these books can help you.

As I noted, I believe we are entering a phase in history when knowledge of the Great Books will once again become a form of cultural capital. But these books have always been a form of human capital. And I think being one of the best is good in itself, even if circumstances never conspire to put you in a position of power.

In my case, attempting to be one of the best means being an honest and open writer. Like Cicero, I am not the most brilliant or original or even the most virtuous, but I am as good as I am capable of being. What I know and feel can be honestly conveyed, and that's because of the training from the Great Books.

I cannot teach you to be the best in your own walk of life. If I thought that I could, I'd simply extract the useful info from the Great Books and give it to you in bite-sized pieces like an Alain de Boton or Ryan Halliday. What I can do, I think, is just write about what it's like being an ordinary person, with no special education, encountering these books cold and trying to experience them in a genuine and honest way. That, to me, is what being a woman of letters is about.

I've been thinking along these lines because I've recently gotten very into Tang Dynasty poetry. All of the major Tang Dynasty poets were civil servants, but they were more courtier than meritocrat: this era of Imperial China was right at the beginning of the examination period, and the examinations were as much a test of birth and character as of Confucian knowledge. As part of the examination you needed to go to the examiners' houses, socialize with them, chat, and examiners often passed or failed you for intensely personal reasons. It was not a path for commoners, or even members of the bourgeois, to ascend the ladder. The highest civil service ranks to the oldest and most powerful families from the Imperial center, and the rest went to highly-esteemed provincial families.

Tang Dynasty poetry is the poetry of the courtiers. This is similar to many other eras in history. Chaucer was a court poet. Vergil was a court poet. Even in Ancient Greece, poetry served a civic function: the lyric poet whose works we have in the greatest quantity, Pindar, composed odes to successful Olympic athletes. Before the invention of the printing press, there wasn't a mass audience for poetry.

And for every great poet that we have, there must've been a thousand bad poets. Many royal courts are suffused by poetry: everyone reads and memorizes poetry, and everyone is an amateur poet. For example, in one of the books I read recently, a Heian-era diary called Kagero Nikki (one of the earliest works of Japanese prose), one of the key things holding together the protagonist's failing marriage is she's a much better poet than her husband, so he calls her over to help compose his replies to the various poems he receives.

Nowadays there's much grumbling that poetry is only read by other poets. But maybe that's...normal? Our understanding of art is nowadays structured by the printing press and mass consumption. Nothing is worthwhile unless it scales. Being a great author is a form of domination: your words enter their head, and you don't even know who they are. Like the great beauty, you are esteemed without esteeming.

But why can't it be a more private, one-to-one relationship? Whose esteem is more worthwhile than that of another poet? Maybe it's better and more meaningful to be a poet amongst poets. In courtly societies, there seems to be much more trust in reputation. You don’t need prizes or big advances or strong sales, all you need is for people to know that you’re a really good poet! And that’s because the only people who really matter are the people inside the Imperial city. It’s kind of like being in high school—you don’t need to be world-famous, you just need the hundred people in your class to know that you’re hot shit.

The difference is that the Imperial City is a hell of a high school. When you’re dealing with, you know, rich and powerful people, the stakes are high. If people like your poems—you can gain genuine preferment, genuine rank, and status and wealth.

But that’s the world we are once more entering. I’m reminded of a truly terrifying article I read recently in the Baffler which talked about how the richest people have fortunes so large that their private wealth managers (their “family offices”) basically act as private equity firms and have the power to reshape economies all on their own. Soon enough, the only path to power will be through appealing to people who have family offices.

When reading a contemporary poet, it would be gross in the extreme to read them sociologically. I really like the poetry of Ai, for instance, who is a multiracial Native America / White / Japanese / Black poet. But to say, "Wow, she gives me an insight into the psyche of Native people" would be insulting.1 Contemporary poets are judged on their merits vis a vis other contemporary poets.

That's not how we read the poets of past eras at all. Eliot gestured at this in his essay "What is a Classic?" when he suggested that a classic is a book that encapsulates a mature culture. When you read Vergil, you’re gaining the full essence of Augustan Rome. I think one outgrowth of this thought process—something Eliot developed in some of his criticism—is that some writers are great, but they’re not of their own time. For instance, Plato is the greatest and most talented writer of Classical Athens, but the world of his books is so genteel, aristocratic, and refined. Thucydides, in contrast, conveys a good mix of the barbarism, raw ambition, and intelligence of Athens. Plato seemed to have contempt for the democratic side of Athenian society (as did most Classical Athenian writers!) so it comes through in Thucydides in a way it doesn't in Plato.

Reading the Tang poets (I've mostly been reading Tu Fu), I've been reflecting on how much of my aesthetic enjoyment comes from the pure shock and dislocation of physically being transported to, say, a mountainous hill-side in war-torn Guangzhong, or to a thatched-roof cottage in Sichuan, and how much comes from the individual talent on display?2

Probably 90 percent of what I feel comes from the former, if I'm being honest. And that's fine! That's the other nice thing about the Great Books. You don't need to judge them. They're already good. You just need to experience them.

But then the question becomes, what do I get from Tu Fu that I don't get from the history of Tang Dynasty China that I'm reading concurrently? How is reading Tu Fu improving me, turning me into one of "the best"?

What I think, if I am being honest, is that all great poems are, at their core, cliches. War is hell, beauty is truth, pleasure is all that matters. But the poem enlivens the cliche, makes it live. And it's only through reading the poem and understanding it that you gain what it has to offer.

Take the following, for instance:

Ballad of the Firewood Haulers

K'uei-chou women, hair turned half-white, forty years

old or fifty, and still sold into no husband's home:

no market for brides in this relentless ruin of war,

they live one long lament, nothing but grief to embrace.

Here, a tradition of seated men keeps women on their feet:

men sit inside doors and gates, women bustle in and out.

When they return, nine in ten carry firewood--firewood

they sell to keep the family going. Old as they are, they

still wear shoulder-length hair in twin virgin-knots,

matching hairpins of silver holding mountain leaves and

wildflowers. If not struggling precariously up to market

they ravage themselves working salt mines for pennies.

Make-up and jewelry a shambles of sobs and tears (indecent

little place), clothes cold, besieged at the foot of hills--

if, as people say, these Wu Mountain women are such

frightful things, how could Chao-chun's village be so near?

The meaning is very plain. War depopulates villages, leaving women without husbands or children. They struggle to survive, to care for their relatives, and in return they're insulted, blamed for their lost femininity. The last line is particularly clever: Chao-chun was a famous beauty in the Han dynasty. He's saying if the women of this remote area are really so ugly, how come this beautiful woman came from near here.

The effectiveness comes from the details, from the seeing. The women wear makeup and jewelry while they work. They bustle around while the men (not even their husbands) remain seated. Their hair is still pinned up as if they were unmarried.

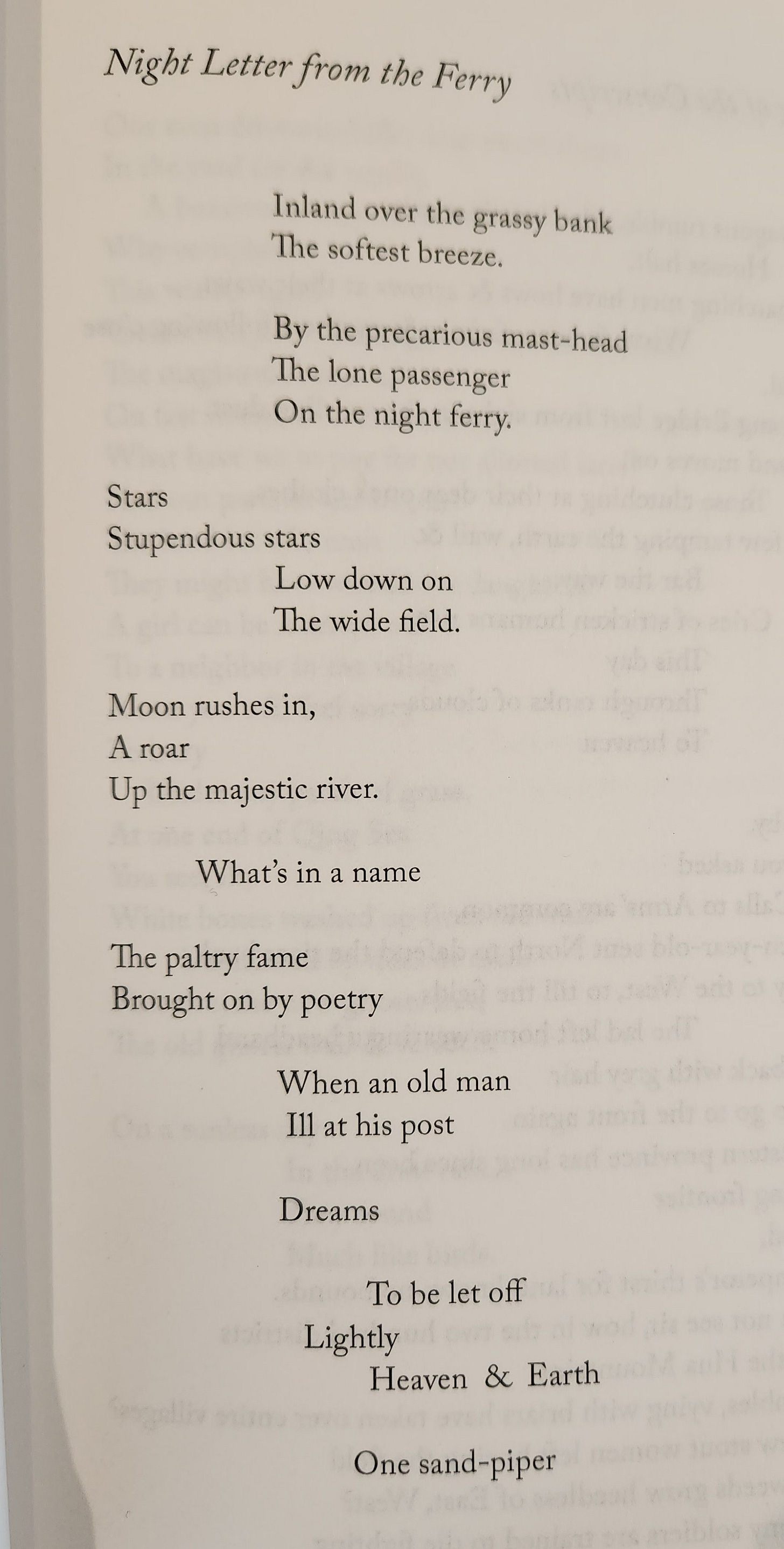

This is in translation, so we aren't reading his original words, and I'm told the effect of the Chinese ideograms is very different, much more allusive. A friend recommended this Wong May translation of some of Tu Fu's work, which gives a very different effect (I attach pictures of the poem both in the Wong May and David Hinton translations, apologies to the vision-impaired, it's too difficult for me to transcribe both right now).

Wong May

David Hinton

In the background of Tu Fu's writing lies the An Lushan rebellion, which killed or displaced almost thirty million people and completely altered the political and social environment of northern China. He was almost forty when the rebellion began. He'd spent most of his life until then in relatively comfortable surroundings near the capital (though he did do an unusual amount of traveling as a youth). His official career had been disappointing (he failed his examinations twice, at least one of them for political reasons) and only achieved relatively low rank, but he was well-regarded and highly born (his mother was the grand-daughter of an emperor). All of this changed with the start of the rebellion, which began with the capture and sacking of the Imperial City, Chang’an. For the rest of his life, he would travel with his family from one province to another, looking for safety and respite from war. Almost all of his greatest poems were written in that twelve year period.

The problem with writing at length about Tu Fu is that the takeaways are almost too obvious. We too will see dislocation in our lives. We too will face disappointment. We too will have to bear witness to suffering. The beauty of Tu Fu is that is also a family man and a good friend, and his sorrows intermingle with simple pleasures. Poetic fame brings him no respite, but a single sand-piper does.

The meaning is too obvious! You can't explicate that! What matters is the aesthetic experience itself, which is the pathway through which his sadness and serenity become our own.

And yeah, you know who would be super-impressed if you quoted a Tu Fu poem to her? Hillary Clinton. That's how you're gonna get ahead in life; you heard it from me first.3

Books Mentioned

China’s Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty. Mark Edward Lewis

In The Same Light: 200 Tang Poems For Our Century. Wong May (trans.)

My favorite book of hers is Vice. Ai writes dramatic monologues, where she often takes on the persona of complex, troubled men.

One thing that the democrat is apt to find offensive about great literature is that it lends a distinctly aristocratic shape to our understanding of the past. Tang Dynasty poetry is the Tang Dynasty for most people, but Tang Dynasty poetry is the work of highly-educated courtiers. This means that our vision of the Tang Dynasty will always be skewed towards, say, men, towards civil servants, towards Han Chinese people, towards the Yellow rather than the Yangtse river basins, and the like. But so what? The choice isn’t between this literature and some other equally lively, but more democratic, vision of the past. It’s either this or nothing. Moreover, we’re hardly doing a disservice to the women and peasants of that era—they’re dead and gone. In a very real way, the Tang Dynasty only exists in our mind. There is no separate democratic Tang Dynasty that we are ignoring.

I’ve been fascinated in the Sam Bankman-Fried case by the fleeting mentions of Michael Kives, a former Hollywood agent and current private equity guy, whose rise to fame began when he interviewed the Clintons for an article for the Stanford Daily on the occasion of Chelsea’s graduation. I’ve looked and looked for any trace of wit or charm in this man, and it’s hard not to see him as just another of the smarmy suck-ups that I went to school with. He is a courtier, but the kind of courtier you’d expect to find in an oligarchy: a flatterer and a fixer, someone with purely instrumental value—the guy who knows other guys. This is the type that will soon be superseded by more charming and cultured people.

I like this piece, thank you.

I teach arts policy, and so have my students read some of The Republic not in a “great books” way, but as an introduction to the eternal question of how we ought to evaluate art, and secondarily, how should we think about art and children’s education. These are challenging intellectual questions, but ones also that will be directly a part of their work, at least at a high conceptual level.

These are not “elite” students, so I feel pretty certain for the vast majority of them their parents couldn’t care less, although I agree it does grant a touch of cultural capital as well as (my concern) human capital.

But they enjoy it! It is provocative, a great way to introduce the big questions (they’ll also read Hume and Tolstoy on this along the way), and ideas that have not exactly faded, even if the cultural scolds in our midst haven’t read Plato themselves.

Maybe sometimes it's too easy to talk ourselves into "nobody reads X" any longer? I used to try to fend off Mencius Moldbug at my old blog because he had an idee fixe that no one read Carlyle, which was rubbish--but his political project required believing that no one did, so they didn't in his mind. On Plato, for example, there is this: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674971769, but hardly only that.