The North Korean Writing Workshop

This exemplary piece of fiction has been acclaimed and lauded throughout the world—in the United States, numerous couples have been saved from divorce through its wisdom, which is in turn the wisdom of the North Korean state. Unfortunately, in a bourgeois Western democracy, the harmonious interplay between government officials, private life, labor, and intellectual activity is impossible, because of the profit motive. Nonetheless, this work of fiction has inspired even the benighted workers of the West with the possibilities inherent in socialism.

In studying this work, let us particularly commend it for the focus on married and family life. The family is the basic unit of society, and only through the strengthening of the family can the state and society be strong. The author recognizes that a happy family can not be mandated by the state—that a man and a woman must choose what is good for them, must actively choose to be happy and to treat each other with kindness, and our strength as a nation flows from this collective choice.

In writing your own works, please follow the example of the author Paek and attempt to produce situations that model the full contours of permissible ethical action.

These were my notes from a short course I took on the creation of literature, and I took them to heart. I studied every aspect of the author Paek's achievement and tried to model it in my own writing. My particular interest was in hero tales, and I spent five years attempting to write a bandit tale, set in the Joseon era, for the newly-opened "fantastic literature" competition. Unfortunately, my manuscript was not selected as one of the winners—it was returned with some notes regarding the believability and coherence of my fiction.

Later, after my defection, I sent the manuscript to several South Korean publishing houses, and they told me that my work was too unpolished, too untrained, too lacking in spectacle and intrigue, and that North Korean fiction of the sort I'd grown up reading was backwards. South Korean stories and movies and films were, in truth, the envy of the world and were avidly read and consumed everywhere. The cultural products of North Korea were trash, produced on the whim of the ruling class.

I accepted their judgement, and now only write in my private time, for my own amusement. My tales of the Joseon-era are printed out and distributed to friends, who say they are entertaining. A coworker called me truly astonishingly entertaining, saying no, no really, this is great. This is the best I've ever read! When will you send me the next chapter!

I do not think that my hero has any particularly Northern quality. I do not have strong opinions on the economic organization of society. I merely wish to tell a tale about a person who perseveres, displays kindness, and chooses to engage in correct actions. I understand that my skills or artistry are lacking, according to the lights of both North and South. Some friends have said I am trapped in the middle—too free for the North and not free enough for the South—but I disagree. If there is a singing competition and one hundred singers compete, then only one can win. The second-best singer would be second-best both in the north and in the south, but that does not mean the second-best singer cannot sing in her living room for her own family.1

Afterword

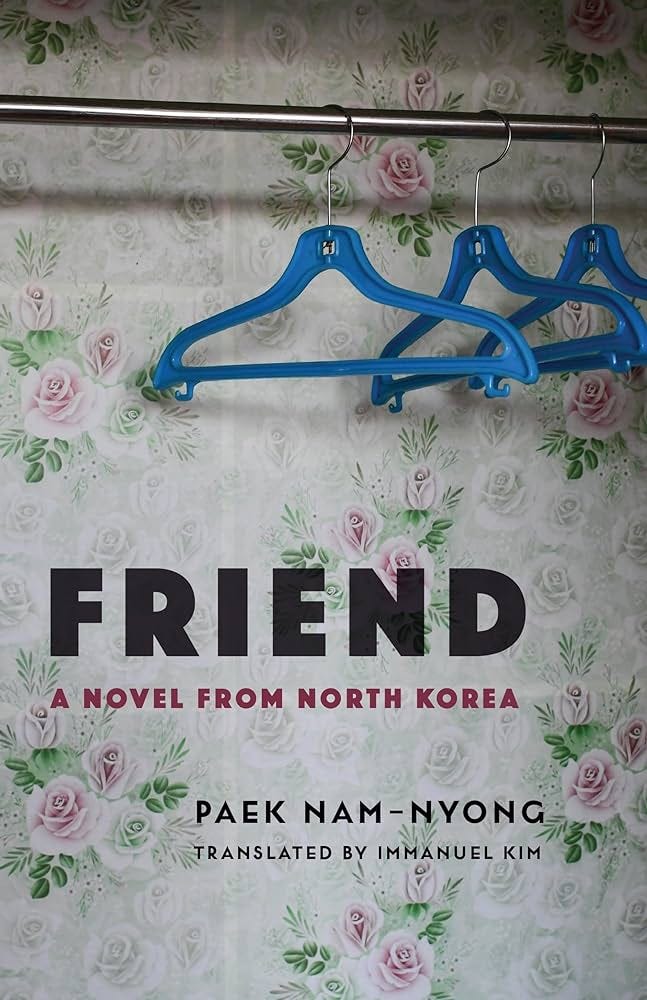

Apologies, I had another post scheduled to go up today, but I figured since it was July 4th nobody would read it, so I quickly threw together this one. It’s inspired by the North Korean novel Friend by Paek Nam-Nyong. I read this book in a day or two and was impressed—it’s shockingly readable and entertaining, with genuine insight into the human condition. The protagonist of the book is this judge who starts meddling in a divorce case that involves a star singer who’s married to an unsophisticated lathe operator.

She realized that divorce was not simply a legal process concluded in the privacy of the courtroom but a public matter with her entire community involved. She felt as if she were being weighed on an ethics scale, naked and vulnerable in the critical eyes of the disapproving public.

Divorce was the only option for her.

She realized that to go through with the divorce, she would have to persist and endure public humiliation, sacrifice her fame and status as a celebrity, and be ostracized from the large family called “society.” The divorce would be a detriment to her livelihood, an inestimable, insurmountable blow to her career.

Oddly, because it’s from a totalitarian communist state, it’s a profoundly bourgeois novel—it’s about the ways that work and aspiration and social status impact our married lives. For the first half of the book, you could be reading a novel from anywhere—in the latter half, some hints of ideology creep in, but it’s a decent, humane novel, about situations that could arise anywhere. I really can’t stress this enough—I found the novel’s depiction of the ways that marriages slowly fall apart, especially under the pressure of competing jobs and aspirations, to be really thoughtful and well-observed, and I count this novel as a genuinely good book—the equal of most contemporary literary novels I’ve read. Indeed, it so strongly resembles a work of contemporary literary realism that it’s almost uncanny.

Longtime readers will know that I’m fascinated by the Soviet system for producing literature. In the Soviet Union, the Writer’s Union formed almost a state within a state—it had its own apartment buildings, stores, vacation dachas, publishing companies, etc. If you were in good with the Writer’s Union your life was assured and could become the equivalent of a millionaire (this was one of the few jobs in the Soviet Union that could provide its holder with real specie), and some writers had millions of copies of their books printed. Of course it was helpful if people actually wanted to buy and read your books, but that was not required, since there was no real feedback loop other than the political-bureaucratic process. Which is to say, someone might mention internally ‘We printed a million copies of that author’s book last time and had to scrap them, so maybe we should print fewer this time’ but if the author was popular internally or had powerful friends then it’s possible their print runs could continue to be large, or could even expand. I don’t know much about North Korea in particular, but I imagine their writer’s union is similar.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how the ultimate test for any writing is just…does anyone want to read this? Do they want to sit down and spend time with it? That’s the real acid test, the thing that can’t be faked. Will someone take four or five hours out of their day to read this for their own entertainment? This North Korean novel passes that test with flying colors—you open it just because the idea of reading a North Korean book is so amusing, but in the end you’re genuinely entertained.

Sometimes I wonder whether my own writing truly passes that test or not. I imagine even in North Korea there are a lot of aspiring writers (in the Soviet Union, being a writer was, if anything, even more popular than in the US, because in the USSR writing was one of the most highly-paid professions), and that a lot of them are failures and a lot of them wonder why their work isn’t hitting—is it the politics? Or is it just the quality? And, just like in America, a lot of times you simply don’t know.

Further Reading

I think Friend might be literally the only North Korean novel that’s been translated into English. The only other work I’ve found is The Accusation, a story collection by a pseudonymous writer Bandi. He’s apparently a member of the Writer’s Union, but he smuggled out these stories as samizdat. That’s a completely different situation from Friend, which is a state-approved novel that you can buy and read in North Korea itself. Anyway I realize from my quotes and from my pastiche above that the writing might sound a little stilted, but in my experience that’s pretty common in fiction translated from East Asian languages. I think there’s something about the syntax of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean that translators try to replicate sometimes by using slightly off-kilter sentence structure and overly-formal diction. But since I’m monolingual I can’t say for sure!

Another quote, from one of the monologues at the end where the judge tries to set the wayward couple straight:

I am advising you, not as a judge, but as your elderly friend. Starting today, try to think progressively like the youths of this generation and create your own path. Don’t be like an old factory worker set in his ways. Get your act together like an intelligent expert technician. Start by taking care of your appearance. Go to the Engineering College. On Sundays, take your son to the theater and watch your wife’s performances. You’ve been wrong to think that these things are pretentious. I know you can do it, and I look forward to that day

If you want to know about writing in the Soviet Union I highly recommend Inside the Soviet Writer’s Union and The Velvet Prison (about a similar system in Hungary). Both are written from a mid 20th-century perspective, about the much-subtler methods of control that succeeded the Stalinist regime. Under the mature Soviet system, dissident material simply never got published in the first place, while the rewards for publishing acceptable material were so immense that most writers never bothered testing the limits of the “velvet prisons”.

It should go without saying that I really do not think a state-controlled publishing apparatus, particularly within a totalitarian society, is conducive to the creation of good fiction. It would be tedious in the extreme to write a long paragraph here where I enumerate how much I disdain the North Korean government or the system of state socialism—indeed it’s precisely because of that disdained that I’m so surprised this system managed to produce at least one genuinely good novel!

P.S. I just realized this anecdote about the singing competition is a reference to a “strange tale” I read recently while flipping through New Account of the Tales of the World. In the story, the warlord Cao Cao has a singing girl who’s very shrewish and difficult, but he can’t afford to get rid of her, because her voice is so unsurpassed in its beauty. So he finds a hundred girls, trains them in singing, has them compete with the singing girl. The moment he finds a girl who is the superior to his girl in terms of abilities, he has his singing girl killed and replaces her with the new one.

Thanks for sharing this. "Friend" has been on my list to read for a while. I learned about it from substacker Felix Purat, who also recommends it. Also thanks for sharing about Soviet writers, a special interest I have... "In the USSR writing was one of the most highly-paid professions" because as you probably know writers are "Engineers of the human soul." [Stalin] I met a Soviet poet once in a fancy house by a lake. She was on an anti-nuclear tour in the USA with another Soviet poet. I had memorized "It's a weary world, gentlemen" in Russian (Gogol quote) to catch their attention. I asked her openly 1) how young writers [like me] achieved publication, and privately [obnoxiously] 2) with glastnost beginning, did the USSR publish Zamyatin (etc) openly now. (Answer 2) She came quite close in the smallest voice that was still discernible, "Little bit." Afterward I felt quite bad for asking and possibly putting her in danger. (Answer 1) Some kind of breezy, open committee discussion process.

Surprising to hear about a novel from North Korea that manages to be both entertaining and insightful, especially given the restrictive environment and everything that one has heard about the place through media. Hope to read the book some day. Thanks for the fascinating write up.