Lonesome Dove grew on me

After reading all these Westerns, I figured that I ought to read Lonesome Dove, because it’s the most famous Western. This book won the Pulitzer in 1986, but that's not why it's famous—many books have won the Pulitzer and been forgotten. It’s famous because even today people still read this book and love it.

So I started to read this book. And I found the beginning to be extremely tough going. I have rarely been so bored. The book is set in the 1870s, and it's about these two men, Augustus McCrae and Woodrow McCall, who are cattle rustlers. They live in Texas, on the border with Mexico, and they periodically head down, steal some Mexican cattle, and drive them north of the border to sell.

Augustus and Woodrow used to be Texas Rangers, and their rustling operation—'the Hat Creek outfit'—also employs several former members of their company, Josh Deets, who is Black and an expert tracker, and Pea Eye Parker, who is somewhat useless. Nearby there is a tiny, barren, treeless town named Lonesome Dove that is also full of various grotesques who I won’t bother to describe.

A former member of their ranger company, Jake Spoon, comes rolling through. Jake is a gambler, who's on the run because he accidentally murdered a dentist in Arkansas. He convinces the guys that there's big money to be made if they can drive a herd of cattle all the way up to Montana.

And, slowly, creakily, over the course of 200 pages, this operation gets going.

Much of the early part of the book is in Augustus's point of view, and Gus has a tendency to ruminate, delivering acres of exposition about people before we really get a chance to know them. For instance, here's Gus thinking about Woodrow Call:

The funny thing about Woodrow Call was how hard he was to keep in scale. He wasn’t a big man—in fact, was barely middle-sized—but when you walked up and looked him in the eye it didn’t seem that way. Augustus was four inches taller than his partner, and Pea Eye three inches taller yet, but there was no way you could have convinced Pea Eye that Captain Call was the short man. Call had him buffaloed, and in that respect Pea had plenty of company. If a man meant to hold his own with Call it was necessary to keep in mind that Call wasn’t as big as he seemed. Augustus was the one man in south Texas who could usually keep him in scale, and he built on his advantage whenever he could. He started many a day by pitching Call a hot biscuit and remarking point-blank, “You know, Call, you ain’t really no giant."

The book also has a lot of changes in point of view, sometimes between one paragraph and the next, you'll hop into a different person's head. So it can be very hard to keep everything straight.

The beginning of the book is boring because there's no stakes, no sense of danger. Life in Lonesome Dove is relatively slow and peaceful, and the story proceeds at a rather stately pace, with many pages of intrigue over which of these men will get to sleep with Lorena, the woman of the night who keeps a room at the nearby saloon.

Then it got good

After 200 pages, the cattle drive begins. And during its first day, one of the hands—an Irishman we've gotten to know a hundred pages earlier—accidentally rides his horse into a nest of snakes, and he dies, bitten to death by what feels like hundreds of snakes. It is wild, sudden and horrific—the first real death of the book.

Then his eyes found Sean, who was screaming again and again, in a way that made Newt want to cover his ears. He saw that Sean was barely clinging to his horse, and that a lot of brown things were wiggling around him and over him. At first, with the screaming going on, Newt couldn’t figure out what the brown things were—they seemed like giant worms. His mind took a moment to work out what his eyes were seeing. The giant worms were snakes—water moccasins.

And after that the book is a lot better.

The pace steadily accelerates, with more characters introduced, more branching sub-plots that include chases and kidnappings and hangings, and by the end of the book it was impossible to imagine I'd ever been bored.

It also helped that we spent less time in Augustus's head. The joke about Augustus is that the guy won't ever stop talking, and he does seem to have a lot of thoughts and a lot of sanctimonous advice, which all gets a bit tedious after a while.

The book doesn't feel much like the mythic Westerns I wrote about two weeks ago. That's because goodness doesn't have much power here. Augustus and Woodrow are good—they strive to protect the innocent and preserve civilization. And in classic Western fashion, they feel very conflicted about it—all their efforts have civilized Texas so much that they've done themselves out of a job.

Once cattle became the game and the brush country filled up with cowboys and cattle traders, he and Call finally stopped rangering. It was no trouble for them to cross the river and bring back a few hundred head at a time to sell to the traders who were too lazy to go into Mexico themselves. They prospered in a small way; there was enough money in their account in San Antonio that they could have considered themselves rich, had that notion interested them. But it didn’t; Augustus knew that nothing about the life they were living interested Call, particularly.

Given their druthers, they would really prefer to be on the frontier, having gunfighting adventures, which is the reason they go on this cattle-drive in the first place.

But...they don't really have the ability to protect other people. Over the course of the novel, a lot of people under their care end up dead. And even when those people don't die, some pretty horrible things happen to them. And for what reason? Just because Gus and Woodrow wanted an adventure. Virtually everyone in this story would've been better off if they'd stayed put back in Lonesome Dove.

That refusal to see any overt meaning in this activity is what makes the book different from a mythic Western like The Searchers or Shane. In those books, the good guys did good—they protected people and made life safe for women.

Here, that doesn't happen. The safest woman they run across is a woman named Clara Allen, and she basically takes care of herself. In fact she runs away from Gus precisely because he doesn't seem able to really give her a decent life.

The absurdist Western

What's interesting about Gus and Woodrow is they're basically existential heroes. Their task—running this cattle drive—is absurd. It's not really a great way to make a fortune: if they wanted a fortune, easier options continually present themselves. Instead, they're just doing it for the hell of it—because nobody else has done it. They're going further north than any cattleman has taken a herd before, and (as we see in the second book in the series, Streets of Laredo), their feat becomes duly legendary.

Even stripped of all the moral valence, their actions seem good in themselves, just because they're so larger-than-life and entertaining.

This book is definitely not a work of realism. The main characters are certified badasses, able to kill many times their number of Indians and bandits guys. Even minor characters are often able to undertake mythic feats, like Pea Eye, who at one point walks a hundred miles, naked, to bring help to Gus.

But the book creates the impression of realism by indulging in a high body-count. Many characters die, and they often die pointlessly. Even the kinds of characters you don't normally expect to die—like sweet kids and noble simple-minded cowboys—they die too. And they often die without accomplishing the aims that they set for themselves.

But, as many people have pointed out with regards to Hanya Yanagihara's A Little Life, this kind of over-the-top suffering is also a form of sentimentality—the aim is to elicit a strong emotion from the reader and make them feel some kind of deep pathos.

In this, the book is highly successful.

The book is part of a series

Lonesome Dove has two prequels and one sequel. I read the sequel, Streets of Laredo, which I found to be much better structured than Lonesome Dove, because it starts with immediate stakes (Woodrow McCall is a bounty hunter who's called out to hunt a psycho that's robbing trains). It was a pleasure to check back in with our old friends and see what they're up to. This book is much more elegiac than the previous, because the world of Streets of Laredo is much more fully-civilized. Although evil exists in the world of Streets of Laredo, it's often an organized evil: this world is full of corrupt judges and sheriffs and industrialists--the kind of figures who don't exist in Lonesome Dove.

In this world, you also feel like there's a sense of camaraderie between the various mythic figures who are still alive. So when Gus McCall meets a famous outlaw, he feels like he's got more in common with this outlaw than he does with the ordinary people of Texas, because they're both larger-than-life, romantic figures. If you've read Lonesome Dove, I highly recommend Streets of Laredo.

I've heard the two prequels are less good, but I haven't read them so can't say.

McMurtry published twenty-five other novels

Lonesome Dove came out in 1985, and it was his tenth novel. All of his previous novels were realist novels with contemporary or near-contemporary settings. He also published about 15 novels after Lonesome Dove. Some of the post-LD novels were historical fictions, while others had contemporary settings, but his novels after LD tended to be written in broader strokes, with larger-than-life characters and comedic situations.

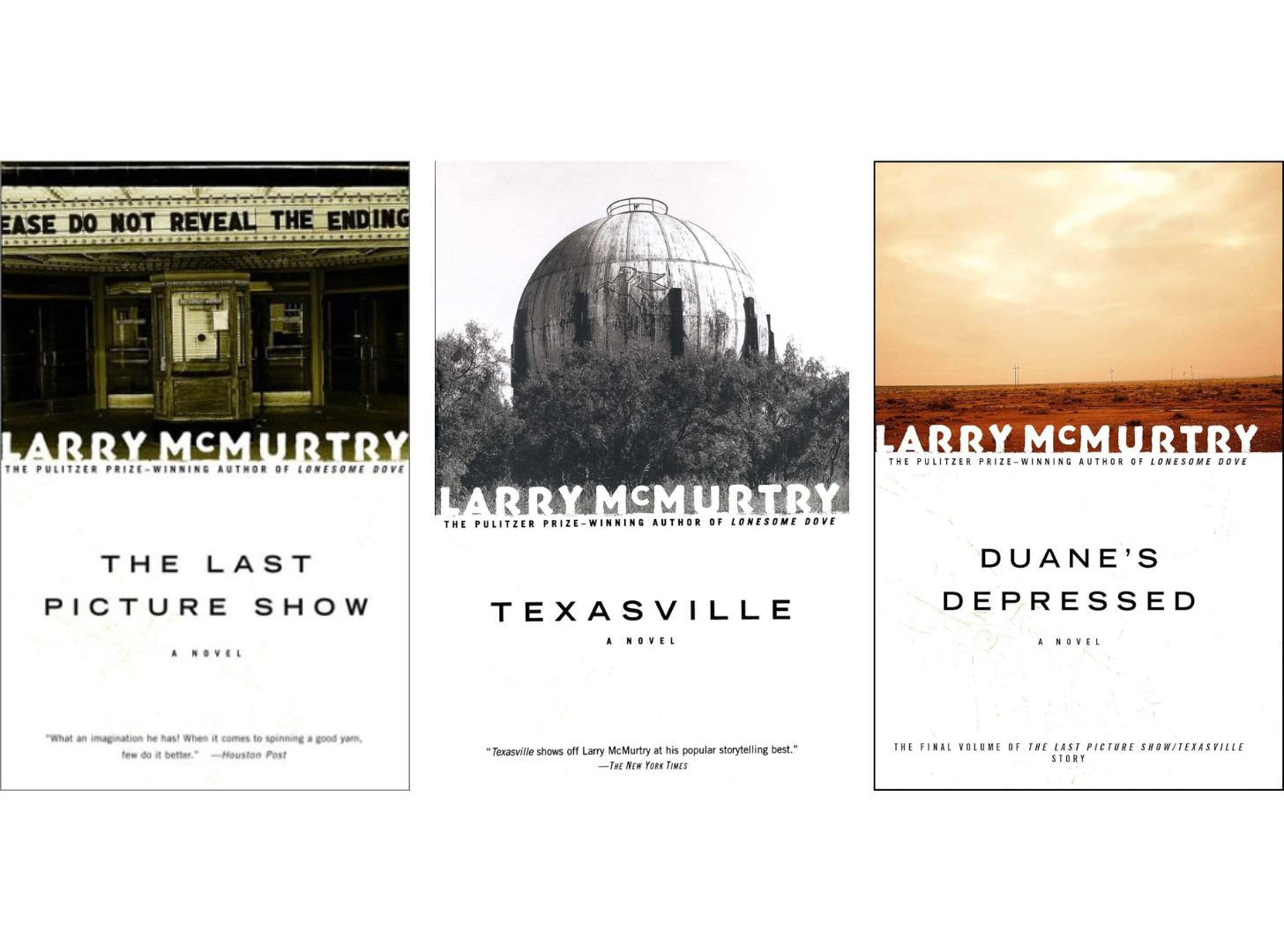

I read five other novels by McMurtry, and I found the quality to be wildly uneven. But the best of these books was his third novel, The Last Picture Show, which was originally published in 1966. It's about two high school seniors, Duane and Sonny, who live in a rented room and share a pick-up truck, and ramble around this little town (Thalia, Texas) plotting how to get laid.

Duane's girlfriend, Jacy, is very hot, but she won't put out. Sonny also spends a lot of time fantasizing about her. This town is incredibly boring, and its full of these adults who all seem sad and defeated. These adults are the future—these adults even say, in essence, I am just like you guys will be when you get older. At one point Jacy's mom advises her to go ahead and sleep with Duane, just so she won't waste her life by marrying him. And then Jacy's mom says:

I probably confused you tonight and I do hope so. If I could just confuse you it would be a start. The only really important thing I came in to tell you was that life is very monotonous. Things happen the same way over and over again. I think it’s more monotonous in this part of the country than it is in other places, but I don’t really know that—it may be monotonous everywhere. I’m sick of it, myself. Everything gets old if you do it often enough. I don’t particularly care who you marry, but if you want to find out about monotony real quick just marry Duane.

These adults keep trying to tell the kids that life sucks! That they are headed for nothing good! But the magic of seventeen is that you're just so full of this unconquerable sense of life. Even if you're on a terrible football team that sucks, and even if your mom is dead, and even if you have no money and no chance of going to college—it doesn't matter, you're still excited to be alive—something this book captures well. I highly recommend it.

The Last Picture Show has four sequels, which were all written late in McMurtry’s career. I read two of these sequels, Texasville and Duane's Depressed. They were written more in the style of Lonesome Dove—big, grotesque characters, and situations that were played for absurdist humor—and the effect was quite depressing, if I'm being honest. Somehow by dropping the realism, McMurtry lost the magic of The Last Picture Show.

I also read McMurtry's first novel, Horseman, Pass By, which Brian Allen Carr told me was his best, but I didn't like it as much as The Last Picture Show—the pacing in Horseman just felt a bit slower, and it didn't hold my interest as much, but the book certainly wasn't bad.

With McMurtry I was amazed by how prolific he was. He wrote almost thirty novels over the course of a fifty year career. I often get the sense that in the 20th century, the line between a 'literary' and a 'commercial' writer wasn't quite so well-defined as it is today. McMurtry was always taken seriously by the critics, but he has many qualities I tend to associate with commercial fiction: he wrote a lot of books, he often returned to the same characters again and again, he wrote at least a few action-oriented books (although these weren't the majority of his output), and his writing was quite plain and accessible.

I would struggle to name a contemporary writer who straddles literary and commercial in the same way. The main name that comes to mind is Tom Perrotta—a deeply entertaining, highly-beloved writer, who's still able to do things like guest-edit Best American Short Stories. Tom Perrotta really has the world’s most enviable career, because he can hobnob in the literary world, but he’s allowed to write stuff that’s fun and readable. Other than him, it seems like if you want to be taken seriously by the literary-critical world, you have to use a really elevated language that puts barriers between you and the reader.

Perhaps a great novel

Larry McMurtry was somewhat conflicted about the success of this book. His aim was to deconstruct romantic myths about the West and show all its brutality, boredom, and pointlessness. But he felt like people really read the book as a Western. The readers saw something glamorous in the book—something he hadn’t intended to put in there—and that’s why the book succeeded. His editor, Michael Korda, often said that Lonesome Dove was “The Moby-Dick of the plains”. But McMurtry said, “I think of Lonesome Dove as the Gone With The Wind of the West. It’s a pretty good book, but not a towering masterpiece.”

I would say...this book is really nothing like a Zane Grey or Louis L'Amour western. This book is dark, grim, deeply troubling. Lonesome Dove operates on totally different heartstrings from, say, Riders of the Purple Sage.

That being said, Gus and Woodrow are certainly larger than life, and the book is full of mythic feats like Gus's solo ride to rescue Lorena from Blue Duck or the scene where they're forced to hang an old friend who's come to a bad end. Without that larger-than-life quality, I don't think the book would work. The ultimate theme of the book is something like...if you're brave enough and strong enough and skilled enough, then you can forge some meaning out of the brutal reality of the West.

Maybe McMurtry didn’t intend that message, but it seems hard to avoid some kind of glamor. Because if you stripped this life of all its glamor, you’d just be left with senseless brutality and destruction, and it would be no fun to read.

Reading more about McMurtry, it feels like the man had an obsession with literary greatness. This NYRB profile is wild reading: at the very beginning there’s a quote where he knocks down Mailer, Roth, and Bellow (“I think all those guys are minor”), and McMurtry also apparently eviscerated the whole canon of literary Texan writers. He also had a similarly conflicted relationship with the old West—he implored writers to move past it, to stop dwelling in that mythic past, and for the first twenty years of his career he only wrote contemporary realist novels.

McMurtry was quite conflicted about ranching, cowboying, and all the rest of the western mythos. His father was a rancher, and McMurtry claims he grew up in a bookless town and had no books in his household. But McMurtry was a poor horseman and didn’t care for ranch life. Like many other men from rural backgrounds, he fled into literature. And it’s clear that he saw a lot that was ugly in the world from which he came.

In the NYRB profile, the reviewer seems unwilling to come out and state whether he thinks Lonesome Dove is truly a great novel, one that ought to endure. I do think that with every writer there is an inflection point that occurs about fifty years after their big book, where we decide whether they make the cut. Jonathan Franzen will also face this inflection point in twenty or thirty years.

I also find myself unable to categorically state that Lonesome Dove is worth other peoples’ time. The beginning is really boring. It’s a huge flaw with the book. Yes, if you stick it out, the book is majestic, awe-inspiring, memorable. Ultimately I came to really enjoy the book, I was tearing through it, I didn’t want it to end.

It's possible that the boringness of the beginning is critical to the goodness of the middle and end—but that doesn't make the boring beginning any more bearable.

In many ways the book is a rewrite of Moby-Dick. It has the same fatalism, the same senselessness, the same focus on mundane detail. If the book succeeds, it’s mostly because it’s ultimately more hopeful, more entertaining, more uplifting than Moby-Dick.

Sometimes I read these books that are a few generations old, and I think, “This book is not really worth the time”. That’s what happened last year with Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy. Other times, I think, “I don’t know whether it’s great or not, but this book is highly entertaining”—that’s what happened with Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcisissm. And sometimes I have a wholly satisfying experience and can confidently recommend the book, as happened with Shane and with The Last Samurai.

In this case, I don’t know. My experience with Lonesome Dove doesn’t fall into any of these categories. Personally, I found reading this book to be a very good use of twenty hours, but that was largely because I was engaged in a broader project of trying to understand the Western. Whether I liked it or not, I was determined to finish. Thankfully, I did enjoy the book quite a bit in the end. But I don’t know if someone else, who just wanted a good and enlivening read, would really get sufficient bang for their buck with Lonesome Dove.

Unlike you, I adored Lonesome Dove from the very first page. I loved the long, slow descriptions of the ranch. And - the thing I don't think you bring out - the humor of it. A lot of the book, particularly in those opening sections, is extremely funny. The account of the Latin motto that Gus puts up, and the description of how he came to put it up - the joke runs for pages, with every new twist to the story adding another layer to it. The relationship between Gus and Woodrow is so touching partly because it is mediated through the constant banter.

It isn't a typical Western, true - it isn't Shane, or The Searchers; but it draws on those while spinning them out into a new, rich world.

But then again, I loved A Suitable Boy as well, so maybe I'm just a sucker for long, slowly elaborated novels. I always recommend Lonesome Dove without hesitation, but maybe I should alert people that it might not be to all tastes.

Lonesome Dove is novelized “manosphere” philosophy/psychology. That’s why I loved it so much. My favorite novel. The gender dynamics in each romantic relationship is just so well thought out and spot on. The other books in the series are good but not as great as this one.