Some topics aren't suitable for literature

And dieting is one of them

My modus with this blog is to start with my current preoccupations (friendship, envy, motherhood, literary careers, etc) and draw on my Great Books reading and historical knowledge to provide some context for my troubles—do my current worries call to mind anything from Plato? Thucydides? Confucius? Proust?

But for the last six months this has proven very difficult, because much of my mental energy has gone into dieting. And there’s no way of sugar-coating it: dieting has no connection to the Great Books.

Yes, of course some know-it-all is gonna come at me now with a Victorian advertisement for belly-busting tapeworms or a Ciceronian dietary prescription, but let’s be real, some things are simply not the stuff of great literature, and purposefully starving yourself is one of those things.

I am very good at dieting. About twelve years ago, I lost 110 pounds, going from clinical obesity to the high end of the normal range for my height. I’ve kept the weight off, more or less, and when I was a man I never saw a reason to go lower: if a man who’s within a healthy weight range wants to improve his appearance he builds muscle, he doesn’t lose weight. Now that I’m a woman, it’s different, and I just want to try being slender.

It’s 100 percent vanity. There’s no disguising that. But everything’s going okay. I’ve got a weird diet that I follow, and I’ve lost thirty pounds (I’m very tall, so I know these numbers will seem large to average-height women) since the start of the year.1

I’m very good at losing weight. Because I was so fat growing up, I used to think that I had a slow metabolism, but I actually don’t. I have a very fast metabolism. I just ate a lot, so I was fat.

In my teens and early twenties, I weighed well above 300 pounds—I think the highest number I ever saw on the scale was 327. I was never not-fat. Even at age twelve, I had a belly, and doctors would tell me I needed to lose weight. Around puberty I somehow went into overdrive and gained weight so rapidly that I got stretch marks on my belly and hips and arms that I carry to this day. I have a very vivid memory of being fourteen years old and creeping down to the kitchen in the middle of the night and just watching myself pour out soda and heat up leftovers and unwrap foil packets, without any volition on my part whatsoever. I just couldn’t stop eating!

At fifteen I eventually developed three perpendicular stretch marks on my face—they look a bit like a cat scratch. I was terrified they would spread all over my body, enveloping me in angry, jagged, red scars. I still have those three scars to this day, on my right cheek. They’re very faded—as twenty-five year old scars tend to be—but I can always find them with my fingertips.

There’s no lesson in this story, by the way. I have no idea why I got so fat. My brother was always very skinny! And although obesity is common in America, when I got to college I was one of the fatter people on campus—within a certain social and geographical stratum, you simply don’t meet very many fat people. I can’t pinpoint with certainty any environmental or genetic cause for my fatness.

The first time I lost weight, it felt very important. I had assumed that because I was fat, nobody could ever be interested in me romantically, and that meant sex / dating / love / etc just weren’t options for me, and I could focus on other stuff. I mean we’re basically talking incel mindset here: lots of unspoken crushes, the few that were spoken were unrequited. But I realize in retrospect plenty of people liked me—I was tall, gregarious, etc. But when it came to romantic things I was just locked-up inside, terrified. It’s a very common syndrome! I meet people like this all the time, even today. Folks who have this feeling that they have absolutely nothing to offer anyone else, even though if they viewed their own situation objectively, they’d say “Yeah, this person is pretty cool.”

The weight loss happened quickly and quietly. I didn’t tell people I was doing it. Most people didn’t comment on it, actually, which was facilitated by the fact that I moved cross-country halfway through my weight-loss period. In fact, my weight loss aroused so little comment that sometimes I wondered if it was actually a big deal. Maybe I hadn’t actually been that fat. But a few years ago I had lunch with my old boss from my DC days, and he said, “You look completely different. Completely different. You are like a completely different person.” He kept repeating it, shell-shocked. He was Colombian, very blunt. So it wasn’t just in my head: I did completely transform my looks.

Losing weight didn’t actually change my life that much. I didn’t feel healthier. I developed back pain (from sitting up too much in bed) and knee troubles (from over-exercising) only after I lost weight. I only started dating after I lost weight as well, so I have no before/after to compare it to. Doctors don’t tell me to lose weight anymore! But my current doctor is so woke that I don’t know if he would’ve told me that anyway (during my most recent weigh-in he said he wouldn’t tell me my weight unless I asked. I told him that I weigh myself every morning).

Anyway, this time the stakes seem a lot lower. I’m monogamously married. My wife has very mixed opinions about my dieting. She’s a doctor, so she thinks being thinner is healthier, but she also thinks you have to lose weight healthily. She doesn’t understand that losing weight is inherently unhealthy. You don’t automatically lose weight by eating salads and nuts and lean meats. They’ve gotta be salads and nuts and lean meats at a level insufficient to sustain life.

And my weight loss isn’t really about health. I’m not exercising (I have too much lean mass already! I need to lose some of that too!) I’m not doing it to feel healthier. It’s disruptive to our home life, since although I’m present for meals, I don’t really partake.

I think it would be fair to characterize this action on my part as a mid-life crisis—some desperate attempt to recapture a totally notional sense of youth. I say notional because when I was young…I wasn’t actually slender! So I’m capturing a youth I didn’t even have.

Boredom is definitely a driver. You get into your late thirties, and you have a wife and a mortgage and a child and a career, and so many things are locked into place, so you look for things to amuse yourself and provide some sense of aliveness. I guess this is in the Naomi version of deciding to run a marathon.

To bring this full circle, you see the problem here from the Great Books blogger standpoint? My current behavior would’ve been incomprehensible to anyone born before yesterday. I mean, looking into the past, a few examples do come to mind: for instance Queen Elizabeth’s heavy use of cosmetics and the strange flirtations she’d engage in with her court favorites. Or Tiberius Caesar’s decadence behavior, late in life, at his villa in Capri. Or all those early Emperors of China who were always making artificial seas filled with wine. Or the Pharaoh of Egypt who got sad one day and asked his vizier how do I be less sad, and the Vizier said, okay, take twenty pretty girls and make them take off their clothes and wear only nets, and then have them row a boat up and down the Nile while you sit on the shore and watch them.

Like, my dieting behavior is decadence. It’s just decadence. It’s the thing the Great Books are always warning you against. There’s simply no way to write an essay where I can believably claim that it’s reputable or acceptable for a thirty-eight-year-old woman to engage in months of calorie restriction just to get from a size 10 to a size 4. And yet that’s what I’m doing. What can I say?

The glib and easy maneuver would be to say, “I know what I’m doing is wrong, but I choose to do it anyway.” A friend of mine said the easiest way to avoid aggression from other women who’re envious you’ve lost weight is to just perform a bunch of soul-searching about it: “I really don’t believe in dieting and I am so worried about the terrible messages this could send to the kids, but I just really felt that for my own personal happiness I could be so much healthier, but I don’t know whether…” blah blah blah ad nauseum. As long as you pretend you’re miserable about it, people will feel better.

But I don’t actually think trying to be thin is wrong. I do think it’s self-centered and frivolous, but so what? That’s what life is now: you create a set of somewhat arbitrary goals, and then you pursue those goals. It’s a very different life from the one led by, say, Cicero. There’s no call for me to go into the forum and defend a man wrongfully accused of murder. There’s no Catilinarian conspiracies for me to foil.

I think there’s a tendency amongst people like me—antiquarians, let’s call us—to act like tradition is good and community is good and convention is good, except when we’re talking about our own tradition and our own community and our own convention. Because surely being a 21st-century member of the creative class is also a historically-bound phenomenon, with its own traditions and rituals. And our particular mode of life revolves around the development of the private self. Like, this is decadence, but it’s not a heedless decadence. Starving yourself to get thin is similar to filling a lake with wine, because it’s extremely self-centered, but it’s different in that it involves a certain kind of mortification and deferment of pleasure. This is characteristic of modern life: we have great freedom, but only within certain bounds.

When I read Freud last summer I was struck by the fact that the reality principle and the death drive and the super-ego are all terms for the same thing. They all represent the natural bounds of our desires. The id seeks self-gratification, but reality imposes boundaries on self-gratification. The super-ego is our internalized sense of those boundaries. The job of the ego is to negotiate between the id and the super-ego, so we only pursue those desires that aren’t self-destructive and that have a chance of fulfillment.

But it’s an inherently unstable arrangement because if we look at reality dead-on, we realize…we don’t matter at all. There is no reason for us to exist. There is no reason any of our desires should find fulfillment. Reality almost seems to demand our annihilation. The job of both ego and super-ego is ultimately to shield us from this truth. The super-ego translates the reality principle into a set of rules and directives that we experience as shame or as conscience—by taking the reality principle into ourselves, internalizing it, we gain a sense of control, so we don’t perceive reality as something imposed on us externally.

But if we take in too much reality, develop too many rules, too much control, then our ego starts to fight a war with the id, and we develop repressions. But there’s nothing insane about this! Most desires really are foolish! It’s not that the neurotic person is illogical—often it’s that they’re seeing too clearly.

For instance, if someone develops delusions of grandeur, then that is in some ways a logical response to an uncaring world. If you confront the fact that the world really doesn’t care what you do and whether you live or die, then how can you keep existing? Well, if you’re facing extreme obstacles, then you need an extreme motive to resist—and if you’re a messiah or a secret genius, then you have a reason to keep going even in the face of the demonstrable indifference of the world.

I think Freud never really resolved the fact that resistance to the death drive is inherently illogical. His thought was that the id is really the source of life: it’s the source of all our positive drives. And when people repress their positive drives, then they’re cut off from the energy that would help them live and thrive. So he’s like, let’s un-repress the id. But I think when you bring those drives out into the open, you often realize how truly difficult they are to satisfy: sometimes the very potency of our drives is the problem.

Take the person who desperately wants love and is unable to find it. She has three ways forward. She can attempt to satisfy her desire for love—but that requires the cooperation of other people (i.e. the cooperation of reality). If that cooperation isn’t forthcoming, then what’s left? Well, she can try to repress her drive or she can redirect it. Repression involves telling herself she’s uniquely unlovable—uniquely fat, unworthy, undeserving of love. This is the reality principle: she’s bringing down the strength of her drive so she can survive. Redirection is trickier, this usually involves an element of neurosis: it almost always involves saying, I am somehow special—I am too intelligent, too wonderful, too different, and hence other people can’t understand me. Then, depending on the story she’s telling herself, she has to find ways of strengthening that redirected story. For instance, if she tells herself she’s too brilliant, then she needs to go out and do things that feed that self-image, etc.

But ultimately it’s a losing game, because the reality is…she’s not too brilliant to find love, she’s not too special…she’s simply unlucky. It’s really an insuperable problem!

Our only saving grace is that our drives are indeed so powerful. Ultimately our drives come to our rescue. They provide our motive power. And even if they never get satisfied through primary activity (i.e. by finding love, respect, community), our ego is so cunning that it can continually redirect and move around the energy of our drives so as to occupy us and give us reasons to keep living.

But this kind of simulated, internal, private existence wasn’t really the province of literature until about three hundred years ago. And that’s why you can’t only read the Great Books—you’ve gotta read other shit too!

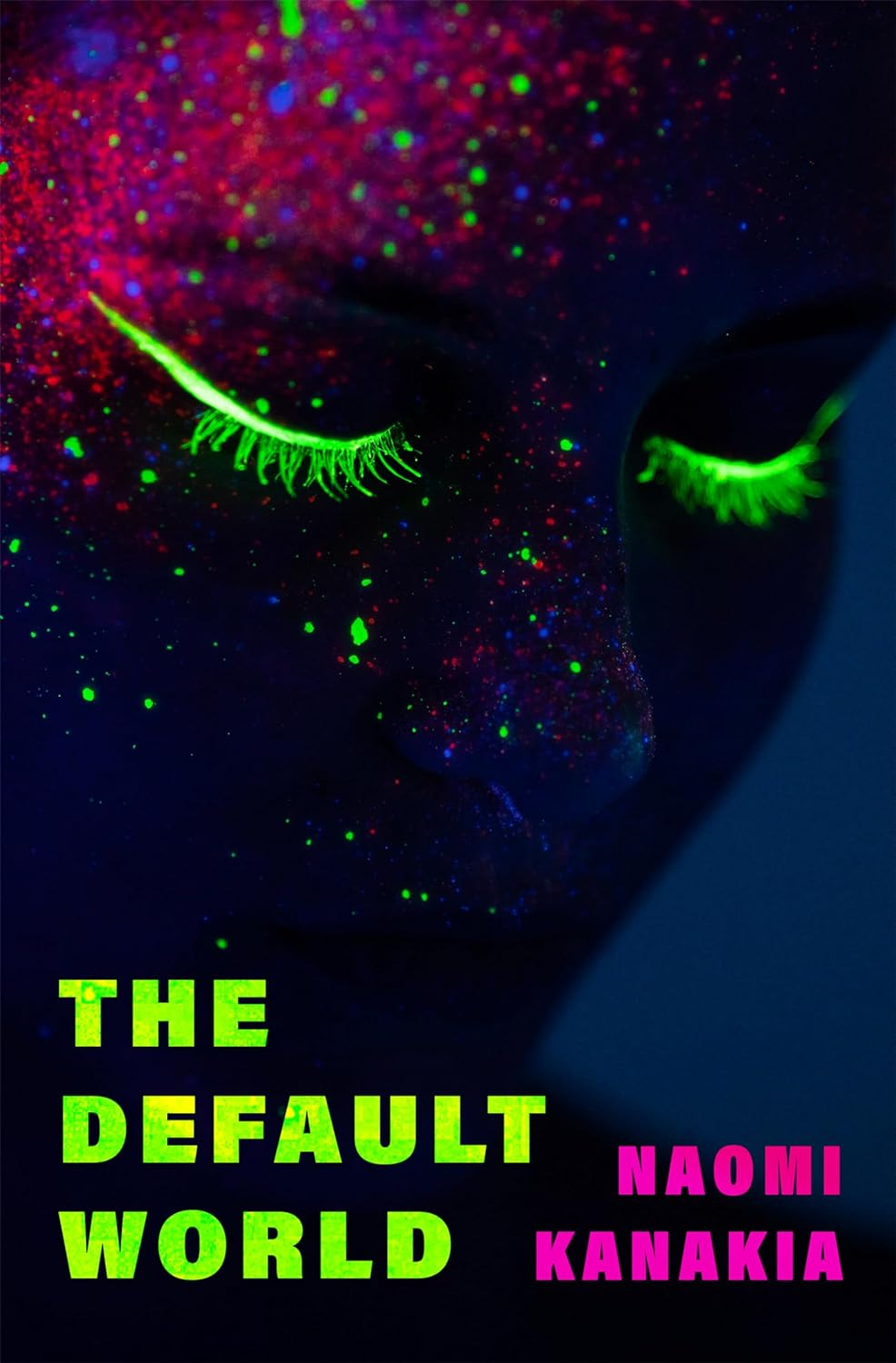

Like my novel! My upcoming literary novel about a bunch of hedonists (and their shame over their own hedonism!). The release of The Default World in two weeks is the culmination of my decade-long quest for a serious (i.e. non-teenage) readership, and the energies released by the incipient publication of this book are quite obviously (at least to me) the reason for both my dieting and for this blog post!

Preorder it here. I also have events forthcoming in SF (May 30th) and NYC (June 6th). Click on the links to RSVP.

I don’t do real diets. I always do made-up cobbled-together diets. For instance when I was losing weight in my twenties I spent a year just eating frozen pizza: four Red Baron’s 3 Meats French Bread Pizzas per day, 380 calories each, totaling exactly 1520 calories per day. I put tapatio sauce on the pizzas: they were delicious.

“no call for me to go into the forum and defend a man wrongfully accused of murder.” I mean… is there not? There’s no shortage of wrong or sad to fix or work on. Though I think writing and caring for your loved ones is plenty meaningful enough!

I enjoyed the honesty here.

Enjoyed these musings as someone who lost a similar amount of weight earlier in life. The self-abnegation becomes a pleasure, not having dessert can be the best dessert of all! It's counterintuitive and can be taken to extremes, but sometimes I wish I still felt a little more of that!