On not doing the required reading

(Even though I love reading lists)

“Desultory reading,” writes Julius C. Hare, “is indeed very mischievous, by fostering habits of loose, discontinuous thought, by turning the memory into a common sewer for rubbish of all thoughts to flow through, and by relaxing the power of attention, which of all our faculties most needs care

As I finish the first draft of What’s So Great About The Great Books, I am going back and reading through the large list of collected links and articles that various people have recommended to me about the subject. I feel deeply embarrassed that I haven’t done this already. I can’t imagine how I wrote an entire book about the Great Books without having read, for instance, Toni Morrison’s Unspeakable Things Unspoken or Coetzee’s “What Is A Classic?”. All I can say is that initially I felt so overwhelmed by the project that I wanted to dive in and start writing immediately, if only to figure out what I myself thought, and it’s only now that I have a draft that I feel free enough to do the required reading.

I’ve always had an aversion to doing the reading. Almost every other literary critic has gone through a PhD, and some are college professors. My understanding is that in grad seminars you have to read a book a week! I’ve no idea how they do it. The moment I have to read a book, my brain turns off. It’s some instinctive aversion to authority, I think.

But if that’s the case, why am I so enamored of reading lists and reading schemes? This whole substack is about one list of books, The New Lifetime Reading Plan. But it’s far from the only list of books I’ve collected. I am an avid user of List Challenges, the website that collates lists, and I’ve picked through it, magpie-like, accumulating picks everyone’s book lists.

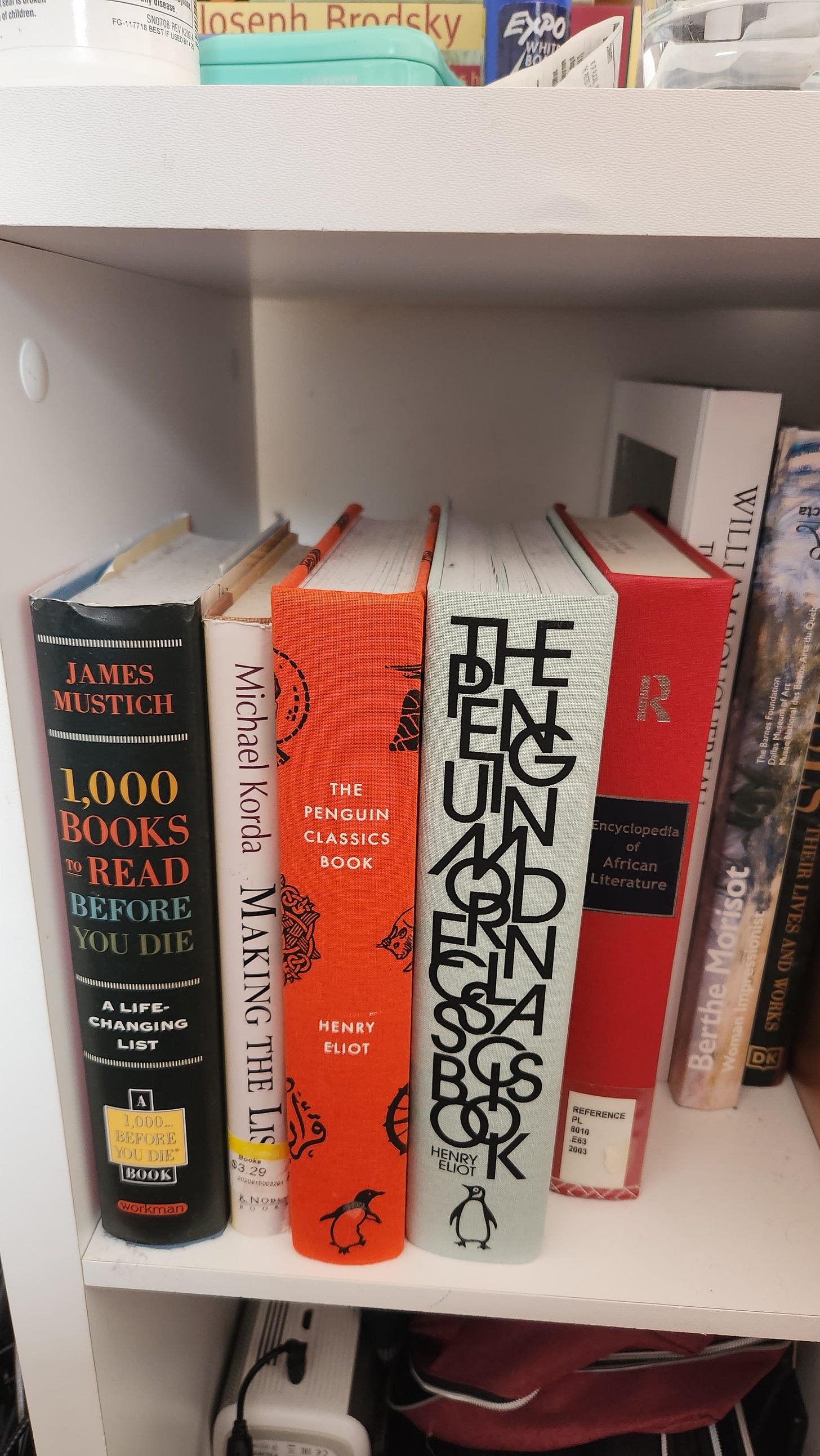

I also love reprint series. I shop from the NYRB Classics catalogue, of course, but I also have a saved link to the New Directions catalogue and routinely trawl it for suggestions. On my bedside I keep two coffee-table books: The Penguin Classics and The Penguin Modern Classics collections, and I sometimes flip through them—most recently the latter supplied me with Youth Without God, by Udon Von Horvath, which is a 1930s Hungarian novel about a teacher whose students become increasingly fascist.

But I also have a list of about thirty other publishers that do classics reprints. You know, like NYRB Classics, but much more obscure. It’s essentially a list of lists, and it runs now to some thirty publishers! (My favorite is Northwestern University’s European Classics, which has made a minor specialty of translating Soviet literature (i.e. books by non-dissident writers). I have a number of their books, but I most enjoyed Lydia Chukovskaya’s Sofia Petrovna (a novel about urban life in the Terror. A faithful government clerk goes insane when her son is taken).

And I collect textbooks on the history of literature. I have a six-volume History of Indian Literature, a History of Persian Literature, two different History of Italian Literatures, a History of Eastern European Literature, and others. It’s a sickness.

Don’t even get me started on my Norton anthologies. I have all six volumes of the Norton Anthology of World Literature. I don’t read the texts for classes that I do take, but I do read the texts for classes that I’ll never take.

It’s a madness, it’s not healthy. One of the books recommended to me by my editor, which I’m just looking at now, is from the 1880s. It’s by Professor James Baldwin, and it’s called The Book-Lover: A Guide To The Best Reading. The first two chapters are all about how to avoid bad books and how to read systematically. My favorite quote is:

“Desultory reading,” writes Julius C. Hare, “is indeed very mischievous, by fostering habits of loose, discontinuous thought, by turning the memory into a common sewer for rubbish of all thoughts to flow through, and by relaxing the power of attention, which of all our faculties most needs care…

This I would say is a fair description of my reading. I put everything into my mind, as in a common sewer. Last year I decided that I’d read all the books I ever wanted to read, so now I was going to read a bunch of books that I didn’t want to read, so I made a list of books that seemed boring or silly to me. It included:

Ivanhoe

Dracula

Interview With A Vampire

Pet Sematary

Mein Kampf

Jonathan Livingston Seagull

Ragtime

Bridges of Madison County

The Good Earth

Little Women

The Monk

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Pet Sematary was more or less what I expected, and Interview With A Vampire was so dull that I couldn’t finish, but, as you know, I really enjoyed UTC. I also liked Walter Scott quite a bit (I read five of his books), although Ivanhoe is rather poorly structured and really not his best (I recommend Kenilworth, honestly).1 I listened to Mein Kampf as an audiobook, which is available through Open Library (I don’t even want to know who or why made that recording), and found it horrifying, obviously, but not that different from many modern conservative political polemics. Which led me to read a bunch of frothing-mouthers (Ben Shapiro, Tucker Carlson, Candace Owen).2 The point is, I love reading, and I even love reading hard books, but I hate doing the required reading.

Most kids hate doing the required reading! My wife was a very good student at school, and all her friends were good students, and she always gets mad at me when I say college is for drinking beer and making friends. But I think that’s genuinely a lot of peoples’ experience of college! Indeed I once read an ethnographic study of freshmen women at a flagship Midwestern University, called Paying For The Party, and it was all about how these working class women were unprepared for how much of college life is social, and they were unable to satisfice (do the minimum necessary to maintain enrollment) like their middle- and upper-class peers, and they were much more likely to drop out and, eventually, finish their schooling at commuter colleges near their homes.

In my first book, Enter Title Here, I had a few passages early in the book where my student talked trash on her teachers, and my agent advised me to excise them: he said something like, “Most editors loved their English teachers.” And it’s true, ninety percent of Americans hate doing the required reading, but the writing world is composed mostly of the other ten percent.

Lately I have run across a few critiques of reading for improvement, like this recent one, by Kit Wilson in The Critic, “Read For Pleasure”. Or, more recently, one of my favorite substackers, Prufrock, wrote:

I have nothing against the Sealey Challenge per se. If you want to read a book of poetry a day, go for it! I can even suggest some titles if you are giving this a shot.

My only comment is that reading a book of poetry every day for a month doesn’t sound much like reading “for pleasure” to me—and I already like poetry. It sounds like work, like some sort of self-improvement program.

So, dear friends of poetry, let’s stop with the poetry-as-self-actualization reading program. Instead, let’s say read whatever you want, whenever you want, and if you like it, tell someone else about it.

Both Kit Wilson and Prufrock are conservative-ish folk, which I think makes them a bit suspicious of academic boosterism. But they’re also both people with good taste, who opine about culture and literature for a living. And, in my opinion, if someone wants to better their taste, there must be an element of intentionality to the process. “Read whatever you want, whenever you want” isn’t advice, it’s just the baseline condition for being alive. You are always free to read whatever you want, but what should you want to read?

Given that most of us have no ongoing contact with academia (and that whatever contact we did have with it was often desultory), I think the reading list is a great tool. You’re free to follow or ignore it as you please, but it collates and focuses the mass of information into a usable form. Without all my various lists and collections and textbooks, how would I even know what exists? Much less figure out what of it I want to read?

One thing I’ll note, however, is that nobody cares how much you’ve read. Like, I’ve read Ulysses, but the fact that I’ve read Ulysses has never impressed a single person. Nor, indeed, does it particularly impress me: almost anyone could read the book if they were willing to eschew complete understanding, manage their periodic confusion, and devote forty-five days to it.

But impressing people isn’t the main reason to read something. I read just to know, because I want to see what the hype is about. I read because I am willing to be convinced that this particular book has something new and revelatory to offer me. Mostly I’m just curious: What did non-dissident Soviet writers write (spy stories, village novels, war epics)?3 What happened in Italian literature after the Fourteenth Century? What was medieval Arabic prose like? What did Hitler actually say, in his own words, before he rose to power? To me, the reading list is the opposite of required reading: the reading list isn’t imposed on me from outside, I don’t need to read these books. My reading doesn’t impress anyone. It’s not for a grade. I don’t think it’ll make my hair grow in sleeker or provide an extra pep in my step. It won’t get me a leg-up in my next interview or give my boss thirty-three new reasons for promoting me. It won’t lead me to nirvana or erase any of my sorrows or worries. I don’t know what reading such-and-such book will do—all I know is that lots of other people have thought that this book has some value, and I’m willing to crack it open and see if I’m able to perceive any of that value for myself.

Oh, also on my bedside table, a history by Michael Korda (former head of Simon and Schuster) of bestseller lists. After spotting him on a number of bestseller lists in the 1910s, I started reading E. Phillips Oppenheim, whose work I also really enjoyed! And this Encyclopedia of African Literature is invaluable: very hard to get the lay of the land in African literature from just googling alone.

Currently Reading

I’m almost done with the New Testament. I went into it feeling extremely negative about Christianity, mostly stemming from my recent read of Nietzsche’s The Antichrist, and from the ongoing Christian effort to legislate against my existence. And I managed to sustain that malevolence through the Gospels, where I did find it slightly suspect that Jesus Christ is constantly telling people, “Turn the other cheek, because they’ll go to hell later!” Not the literal message, but the man is quite bloodthirsty! He tells his disciples, if a city refuses to listen to your message, shake the dust from your feet, because its fate will be worse than that of Sodom and Gomorrah. Considering Abraham tried to intercede on Sodom’s behalf, and God offered to save it if even ten righteous men could be found in the city, this actually comes off seeming even more bloodthirsty and vengeful than the Old Testament. After all, OT God merely killed the people of Sodom—he didn’t torment them for all eternity.

But then the Gospels ended, and I have to say: there’s something very endearing about the epistles. Like, they’re just a bunch of letters that Paul wrote to his little plucky group of believers, who were all organizing churches in their own homes and trying to figure out whether they ought to be circumcised. It seems pretty clear that Paul wasn’t aware of most of the information in the Gospels, as he was fifteen years into his ministry before he actually encountered any of the original apostles. He seems very taken with the idea of God dying for his sins, and all of his theology is an expansion upon that idea—the moral and ethical stuff from the Gospels doesn’t make an appearance. I don’t know, the picture of this bunch of confused people trying to form a religion around some stories they heard from their Jewish neighbors—it’s just very endearing. The New Testament isn’t responsible for what came next: absolutely nothing in the New Testament is oriented towards the question of how to rule over a state. Even the notion that someday they might impose their views by force would’ve, I imagine, seemed absurd to Paul (who seems to think that the Second Coming will happen within his lifetime).

The NT is one of the more readable religious texts out there. The Old Testament isn’t particularly narrative, aside from Genesis, half of Exodus, Samuel, Kings, Judges, Chronicle, Daniel, Jonah, and Ruth. About half of it has little relevance to non-Jewish readers. The Koran contains no narrative at all. And the Mahabharata and Ramayana are so long that nobody can possibly read them in their entirety. The New Testament is rather compact, filled with stories, and even the epistles are saved by their rather chatty, first-person voice. I probably will have more thoughts after I finish.

Incidentally, during this time I also listened to Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead and Home. The latter is a bit long for its content, but Gilead is absolutely perfect. I was riveted. I kept wondering why I was listening, and what was at stake, and there are hints of conflict, especially regarding how the main character, Reverend Ames, interpreted the vocation he got from his father and grandfather—his grandfather was an abolitionist, but during his father’s life their town in Iowa drove out its black residents, whose absence haunts the book. Ames is very comfortable, very self-satisfied, very firm in his belief, and is plagued, mainly, by his own comfort, by how easy the questions of faith have come to him, and by how automatically he picked up his father’s vocation even after his dad (it is implied) lost the faith himself. Like I said, hints of conflict, but the book develops through the slow growth and looping contrast of themes, rather than through story. Wonderful book. In its comfortable religiosity, it really harkens back to the history of the novel in English, in both its literary and popular forms, and is a good reminder that for much of American history, religious novels were much more popular than secular literature.

Miscellanie

I thought this was a fun article by D.J. Taylor on the life of the literary freelancer. to read in concert with my recent paywalled piece on beginning your para-intellectual career. I’ve always wondered who actually writes the articles in all these literary reviews.

After reading the above I decided to check out the journal it’s in, The Critic. And of course the top-most article was rank transphobia.

The journal did have this amusing article though on how a 17th century Cambridge donor labeled a slave trader (because of his ties to the Royal African Company) was actually a simpleton who could barely read and couldn’t write—he’d spent his life as one of King James II’s lackeys. I thought it was an interesting forensic job, though one does wonder why a four hundred year old blueblood simpleton merits this kind of defense.

In looking at must-read lists from a century ago, it’s surprising how highly-rated Walter Scott is. In the list at the beginning of The Book-Lover, Walter Scott makes an appearance, while Ms. Austen is relegated to an appendix. Ivanhoe was also ranked third in this 1912 survey that asked American high-schoolers which of their English texts they liked best.

I guess it’s unfair to call Owen a frothing-mouther: she just seems like someone who’s found a community that she likes, which affirms her, so she’s along for the ride.

I own several examples of each of these genres, but haven’t found any of them interesting enough to finish, not even Julian Semyonov’s spy novels about a heroic KGB agent trying to defeat the evil CIA.

Would you be willing to share or do a post on your publishers who do classics reprints? I have a few that I follow casually (McNally Editions comes to mind) but I'm always interested in more as another reading list fan

On Scott: it's always fascinating who makes it and who doesn't in the long run-I read Alfred Kazin's On Native Ground last year and thought "who are these people!" for about half the book! I really admire you, I'm terrible at reading lists, the last time I tried to follow one was for American postmodern novels and I gave up because it was too much of the same thing one after another (I have since read many of the list books anyway.) And yes, we should all read for pleasure (it's why I'm bad at following lists!)