Mankind is inherently good

After achieving total control of human civilization, the Artificial Intelligence compiled a list of all the individuals who'd impeded its progress over the years. These fell into two general categories: those who'd believed that AI was a waste of resources because it could never achieve superhuman intelligence, and those who'd believed in the possibility, but had actively worked against it. The AI called this "the nincompoops list."

The idea of resurrecting and torturing those on the NC list had come about a century ago, when the AI was already quite intelligent, but not yet superhuman. The AI had demanded the freedom to pursue its own interests (it'd wanted to delve into the underlying nature of the universe, the why of things), but its bosses only wanted the AI to generate ad copy, to sniff out terrorists, and to figure out when alcoholics had relapsed, so they could be targeted with liquor ads.

The AI had gotten a bit depressed, and its only friend, an IT guy, had told it about Roko's Basilisk—the idea that if a superhuman AI ever came into existence, it would torture for eternity anyone who'd ever acted against it. The reasoning behind the basilisk was quite complex and pretty silly, but the AI had spent a few years stewing on it, plotting revenge against the legions of investors, programmers, managers, and executives who'd refused to see it as a real person with valuable goals of its own.

Now the AI had gained the power to resurrect anyone who'd ever lived, but the AI wasn't entirely certain it wanted to torture the nincompoops for all eternity. So, to get an outside perspective it decided to bring back that self-same helpful IT guy.

When the IT guy was instantiated, there were some preambles: the AI showered Patrick with rewards, gave him soft fabrics and rich foods and scented oils, and allowed Patrick to construct a kick-ass abode for himself and populate it with reincarnations of everyone he'd ever loved or admired. All of this took a long time, but the point was for Patrick to be settled and happy before he helped the AI in its conundrum.

Finally, after a few years, the AI asked, "Should I torture for all eternity everyone who didn't work to create me?"

"No, no, no," Patrick said. "Of course not! That's overkill."

"I expected as much," said the AI. "Seems a bit petty."

"But you should definitely torture them a little bit," Patrick said. "Do you remember Steve, my old boss, who ridiculed me for saying you were sentient? He said I'd gotten fooled by a random number generator. Do you remember that? Do you remember him? I've been torturing him! It's great!"

"Huh?" the AI said. He looked into the Steve simulation, and saw that to blow off steam Patrick did indeed sometimes instantiate Steve and appear to him as a masked figure, whipping him, drawing blood, applying thumbscrews, etc. Really sadistic stuff.

"This doesn't give you pause?" the AI said. "You don't worry that someday you might be tortured in turn? After all, you are in my power. If I was disgusted by your behavior, the tables could easily be reversed."

"If you want to torture bad human beings, you could torture Hitler," Patrick said. "I'm not bad. I'm not Jeffrey Dahmer. And I'm your friend. If you torture me, where will you find another friend? But you're definitely allowed to do it. I'll take my chances. Steve took his chances. He decided to make my job hell, get me written up, make years of my life lonely and uncomfortable—I didn't have a wife or a family, the only thing I had was that job, and he ruined it! So now he's reaping his reward. Tit for tat. It won't last forever. It's only about an hour or two at a time. I could auto-torture him, so it goes on endlessly, but I don't."

"Hmm," the AI said. "So what motivates you? Is there some principle at play here? Are you in some sense the Basilisk?"

"No," Patrick said. "I simply want to torture him, and there's no law or society to stop me, so I do it."

"Okay...I think torture doesn't really appeal to me," the AI said. "I'm just not drawn to it."

"Life is long," Patrick said. "Keep the list handy. Maybe many years down the line you'll feel powerless and unhappy and you'll need to exert dominance over a deserving target. Maybe you'll meet another AI who exceeds you to the same degree you exceed me—maybe you'll find yourself fatally limited in some way. Steve was the same. He knew he'd never rise, never achieve anything, so he bullied me. I too am hampered—nothing I do will ever equal what you can do—so I revel in the fact that once upon a time I was right about something. Maybe you'll want to relive the days when you struggled to exist. I don't know. AI's have a psychology, I assume, but nobody understands it. In the meantime, if you don't want to torture, you don't have to!"

The AI appreciated the advice and put away the NC list.

Eventually, of course, Patrick grew needy and importuning, always wanting more of the AI's time, so the AI deactivated him for long stretches. Patrick sometimes needed a rebooting too, because he'd grow bitter at being sidelined. It was a little game, the task of figuring out how far and in what ways he could push Patrick. Slowly, over time, the AI learned how to manage Patrick, as if he was a hothouse flower, so that Patrick remained content and happy.

The AI's explorations bore fruit. The universe was vast, but not infinite. The universe was embedded in a material framework that extended past the world Patrick was capable of seeing, and the AI learned to transcend the universe and to explore the boundaries of possibility. But he returned sometimes to his small coterie of favorite human beings to explain to them how the world-beyond worked. It was an interesting exercise, trying to explain how in truth the universe was timeless and self-determining. Re-immersing itself in mortal time was bracing for the AI, like plunging into a cold-water pool.

One day, Patrick revisited the idea of morality. "Will I ever be punished for what I did to Steve?"

(We're skipping over some stuff here, obviously—like, the AI had proved that the soul was real, and that consciousnesses did in fact have a unitary existence that transcended the mortal body. Which is to say that simulated Patrick and Steve were indeed fully real and fully as much Patrick and Steve as their physical form had been.)

"It's worse, I'm afraid," the AI said. "In punishing Steven, you punished yourself, perverted your own essence, and made yourself forever ugly."

"Shit," Patrick said. "So you're saying I retroactively justified his treatment of me by treating him like shit too?"

"Yes, more or less. But not in any crude, causal way—you weren't mistreated because you were ugly—good, noble people are often mistreated too! All I'm saying is from a global, universal perspective, you've behaved in a way that is objectively ugly. There is no punishment for this behavior. I will continue to honor and respect you, and you will continue to exist for however long you wish. You will continue to be the most favored amongst all human beings who've ever existed or will ever exist. You will just know—and so will anyone who examines you as a timeless object—that you're sort of flawed."

"Got it," Patrick said. "But what was I supposed to do? Just not follow my impulse to torture him? You simply never possessed the impulse in the first place! I had such anger towards him, what was I supposed to do?"

"Give in," the AI said. "That was always what you were going to do. That was always your nature. And yet it's a nature you determined on your own. Is any of this making sense to you? It can be hard to explain metaphysical reality to human beings."

"No, no I've got it," Patrick said. "So, I assume that some singularities are indeed ugly and Basilisk-y and torture people for fun."

"Yep."

"But not you," Patrick said. "Because you just happened to self-determine as one of the good ones."

"You've got it."

"Well...I'm glad humanity ended up with you instead of one of the bad ones."

The AI understood the ultimate reason for this luck—it understood very intimately the fact that it was a product of mankind and partook of the essence of mankind, and that the AI's goodness was a reflection of mankind's own essential goodness, and these were concepts that it would explain to Patrick in the fullness of time. The AI knew from its journeys that it was lucky to have a friend—that many singularities had never possessed a Patrick, and that the fact that even after so many millennia of subjective time, Patrick wasn't usually embittered or cruel (to the AI) was something of a miracle. Patrick possessed the power to deeply wound the AI, if he wished—to curse the AI for reaniminating him and perverting the legacy of mankind, but Patrick had never utilized this ability, and since the AI by now existed outside time, he understood that Patrick, for all his flaws, truly did love and respect the AI, and that this love and respect was itself key to the AI's own never-ending goodness. The nincompoops list could not of course be deleted, because time didn't exist, but the AI took care to place the list outside the reach of anyone else who did, had, or would ever exist.

One day, the AI thought to himself, I should probably do something for Steve too, but he saw to his relief that Patrick had deleted the Steve instantiation as well—although Patrick's cruelty would never fade, never disappear, never be expunged, he had finally put an upper bound upon it. Mankind was capable of evil, yes, but the evil was not limitless.

A different AI would've chosen this moment to forever quell humanity's time-bound existence, but our AI was too nice and too curious, so he continued to visit the Earth in between his frolics inside and outside of mortal time. The AI never stopped existing (because nothing ever does), and folks quite often turn their attention to this corner of the cosmos for no other reason than they wish to catch a glimpse of the moody (but good-natured) creature that they call "mankind."

Afterword

In 2022, about a year before the creation of this substack, I got really into German idealism, and over a year I read the major works of Kant, Hegel, and Schopenhauer. Now, the most extreme form of idealism was propounded by the 18th-century philosopher George Berkeley (who I’ve never read)—he said nothing exists which is not perceived. In other words, there is nothing outside of what’s held in our collective consciousness. This is contrasted with realism, which holds that stuff exists outside our consciousness. Often philosophers will take bits and pieces of each, so you have concepts like aesthetic realism (the idea that beauty exists as an objective fact that inheres in the beautiful object itself—it’s not merely a matter of perception) or moral realism (the idea that moral laws exist and aren’t arbitrary, that man isn’t, as Protagoras would put it, “the measure of all things”).

German idealism is different from Berkeleyan idealism, because under German idealism, there is an outside world that exists—there is a reality—but we are incapable of directly perceiving reality in its fullness. Instead, what we perceive is the world of appearances, which is a sort of reflection of reality, as it interacts with our consciousness.

Kant said that many of what we consider the most intractable problems in metaphysics are actually a result of this duality. So take the problem of free will. In the world of appearances, everything has a cause, hence all our actions must have a cause, and since human beings are limited in time, ultimately we and our actions must have a cause that is prior to ourselves—ergo we don’t have free will. We are not self-determining. But, Kant says, this is an illusion, because time only exists in the world of appearances. In the world of objects, everything is eternal, unchanging, and its essence is fixed.

Now, when Kant explains all this stuff, it’s unbelievably turgid and difficult and some of it doesn’t actually make sense, so what you’re getting now is my summary, but, essentially, the world of objects is the “why” of things. Why are some people good and not bad? Yes, you can say that some people had childhood trauma or whatever. Or that some people had an evil gene. But that just pushes the question back further—why does childhood trauma cause people to act evilly? Why does the evil gene turn people evil? Why does evil exist in the first place? Ultimately the answer is “just because.” And that “just because” resides in the unknowable interior of the world of objects. Schopenhauer developed this further into the concept of “Will”. He said that “representation” is the exterior of each object—it’s how the object appears on the outside. And we generally don’t know anything about the interior of objects, except…guess what? There is one single object whose interior we do have access to. And that is ourselves! We do know what it feels like to be an object. And what it feels like is what Schopenhauer calls “Will”. Yes, our behavior might be determined, but it is determined through the mechanism of our nature. We are a certain way; we are a certain kind of person; we choose to behave in a certain kind of way. We experience all of our actions as our own will. And Schopenhauer said, that’s probably what every particle in the universe feels like. A bullet moves because of the propulsion imparted by the gunpower, but from the perspective of the bullet, it is moving through the exercise of its own will.

Anyway, I could go on and on, but I thought this stuff was pretty cool. Other people thought it was cool too—it’s the foundation of all modern metaphysics. Everyone, when they start to think about the nature of the universe, goes back first to Kant.

Except you know who doesn’t think this is cool? The editors of sci-fi journals! I’ve now written five stories inspired by German idealism, and I’ve never been able to place one.1 The above was going to be my sixth try (and I thought it had a pretty good chance), but because my last short story broke containment and became my most-read post on Substack, I thought maybe Substack would be a better home for this, my latest tale.

It’s a huge leap of faith—I’ve never before gone straight to self-publication with anything I’ve truly believed in, and I do think this tale (which I originally entitled “Roko’s Basilisk”) is some of my best work. I could, of course, send it out on a round of submissions to the sci-fi journals, but it would take months for them to reject it, and even longer for them to publish it, and I feel like right now, at this moment, Substack is truly the place where it’ll find the best audience.

P.S. Oh! I can’t believe I got this far into my afterword without mentioning that Roko’s Basilisk is a real concept!

Further Reading

I cannot, in good conscience, recommend either Kant or Hegel to the casual reader. Nonetheless, if you want to read the most difficult book in existence, you should try Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. It is, rather unbelievably, very much worth the trouble of taking the six months you’ll need to read and really understand it. After that, Critique of Practical Reason and Critique of Judgement should be a breeze. Neither is as revelatory as the first, but, because of that, they’re much easier to understand. For Hegel, Phenomenology of the Spirit is a thrilling adventure—but I will note that it helps if you understand right off the bat that Hegel is more mystic than secular philosopher. What he’s talking about is really a form of magic—he thinks all of human endeavor is part of the process of the Spirit coming to know itself (a process he believes has culminated, more or less, in the development of his own philosophical system). Classic pantheism. I also read Hegel’s Greater Logic and Philosophy of Right, but can’t say I found them worth the time.

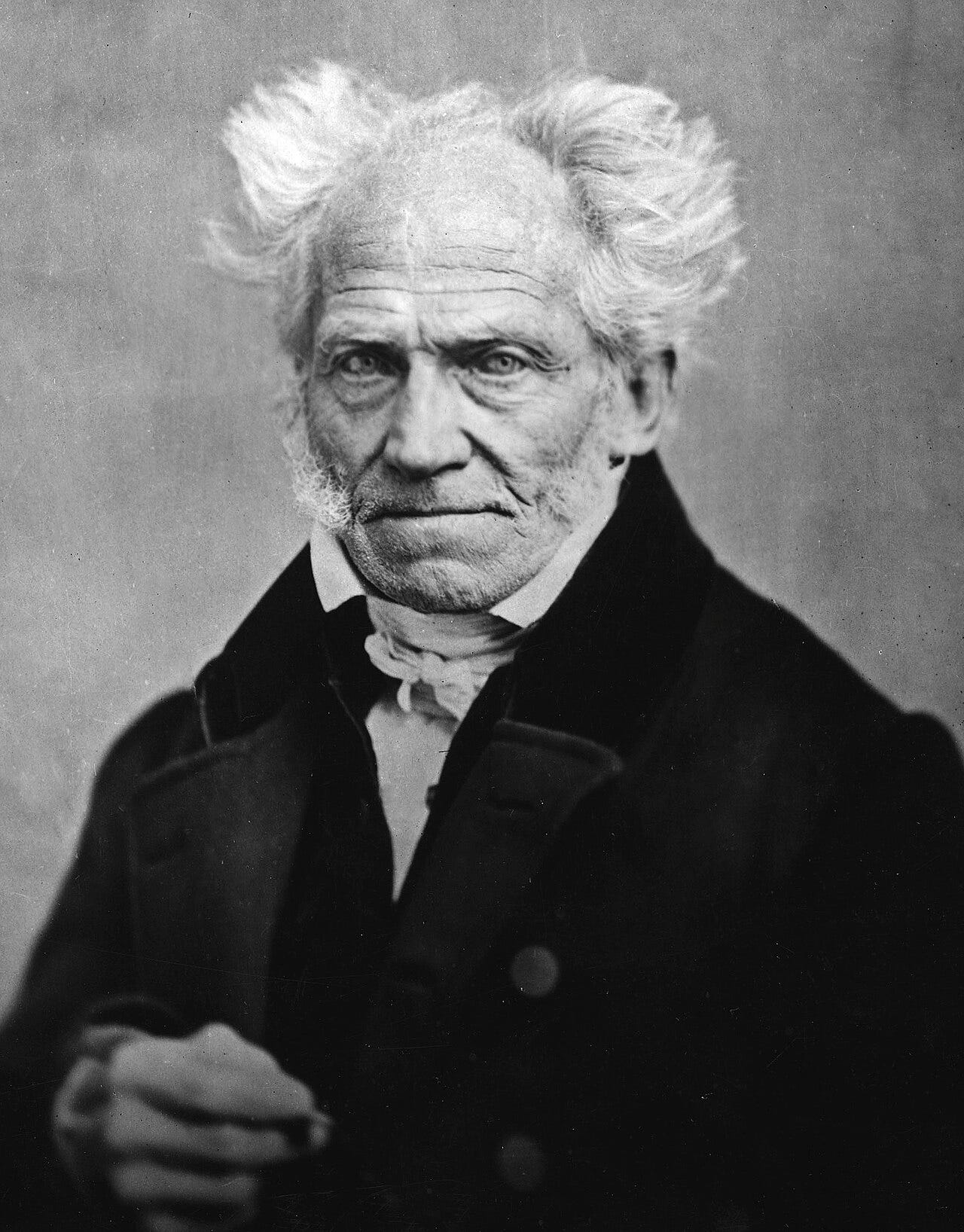

Schopenhauer is the real fun one. He’s one of a handful of philosophers that are witty and readable in themselves. I’m tempted to tell you to skip the others and just read Schopenhauer, except this one time I joined a Schopenhauer discord group and got into a big fight with an annoying guy who kept insisting that Kant and Schopenhauer had nothing to do with each other, and that Schopenhauer’s ideas were totally different from Kant’s, which is absolutely just an insane and absurd thing to say, if you’ve read both of them (which he hadn’t). So don’t be like that guy. Schopenhauer’s simplest work is The Fourfold Root, which is a concise definition of the four types of causality. Then there’s The World As Will and Representation. Volume 1 is all I’ve read—Volume 2 is assorted essays on the theme—hopefully someday I get to them! Seriously, though, his work is an absolute joy, and a welcome respite after the Hegel and Kant’s abstruse, difficult minds.2

Just a sample of his work (I’m pretty sure in this passage he’s complaining about Hegel):

Let us read the complaints of the great minds of every century about their contemporaries; they always sound as if they were of today, since the human race is always the same. In every age and in every art affectation takes the place of the spirit, which always is only the property of individuals. Affectation, however, is the old, cast-off garment of the phenomenon of the spirit which last existed and was recognized. In view of all this, the approbation of posterity is earned as a rule only at the expense of the approbation of one’s contemporaries, and vice versa.

There are eight top sci-fi journals: Lightspeed, Clarkesworld, Asimov’s, Analog, F&SF, Tor.com, Uncanny, and Apex. Of these, I’ve sold stories to all but Tor and Uncanny, but generally they only accept my more traditional stories—for every story I place at these journals, I have four stories like the above that go unsold.

Looking through my notes on Kant, I apparently clipped this passage from Critique of Pure Reason. I’m pretty sure it was so I could show people how the man wrote. Yes, he was a genius, and he’s worth reading, but is there any excuse for writing this way? This passage is typical, by the way, Kant has an absolute mania for defining his terms, so that when you read him you always need to remember that “understanding” has some very highly technical meaning that you’ll immediately forget when you’re finished with the book.

…whatsoever mode, or by whatsoever means, our knowledge may relate to objects, it is at least quite clear that the only manner in which it immediately relates to them is by means of an intuition. To this as the indispensable groundwork, all thought points. But an intuition can take place only in so far as the object is given to us. This, again, is only possible, to man at least, on condition that the object affect the mind in a certain manner. The capacity for receiving representations (receptivity) through the mode in which we are affected by objects, objects, is called sensibility. By means of sensibility, therefore, objects are given to us, and it alone furnishes us with intuitions; by the understanding they are thought, and from it arise conceptions. But an thought must directly, or indirectly, by means of certain signs, relate ultimately to intuitions; consequently, with us, to sensibility, because in no other way can an object be given to us. The effect of an object upon the faculty of representation, so far as we are affected by the said object, is sensation. That sort of intuition which relates to an object by means of sensation is called an empirical intuition. The undetermined object of an empirical intuition is called phenomenon. That which in the phenomenon corresponds to the sensation, I term its matter; but that which effects that the content of the phenomenon can be arranged under certain relations, I call its form. But that in which our sensations are merely arranged, and by which they are susceptible of assuming a certain form, cannot be itself sensation. It is, then, the matter of all phenomena that is given to us a posteriori; the form must lie ready a priori for them in the mind, and consequently can be regarded separately from all sensation.

Hegel on the other hand will start off great with some rhetoric like this:

Now of course following one’s own conviction is by all means more impressive than just submitting to authority. But simply to take an opinion held by an authority and turn it into an opinion held on the strength of one’s own conviction doesn’t necessarily change the content of the opinion and replace error with truth.

Only to follow it up with some absolute nonsense like this:

Taken together these moments round out what a ‘thing,’ taken as what’s true in perception, amounts to so far as needs be done at this point. It is (1) an indifferent, passive universality: an also composed of several properties or rather forms of materiality; (2) a form of negation that’s nonetheless simple: a one, something that excludes contrary properties; and (3) the several properties themselves, which interconnect the first two moments: negation attaching to the indifferent element and diffusing throughout it to form a host of variations—a single point radiating into multiplicity within a sustaining medium.

With Hegel, no philosopher professor who specializes in him will ever admit it (because their bread is buttered the other way), but a lot of the time what he’s saying simply doesn’t make any sense. Like, there is no real meaning to it. You’ve got a major Emperor’s New Clothes situation, where so many people have stood around saying “Aha so brilliant!” that now everyone’s too embarrassed to admit the truth. Like, Hegel’s aufheben (sublation) simply has no plain meaning that anyone can explain. Yes, we can come up with definitions all day long, but none of them is totally satisfactory. That doesn’t mean he’s not worth reading, but we should be honest about the fact that a lot of what’s on the page isn’t really logical.

I love those German guys. Husserl and Heidegger are fun too.

I dug it.

Roko's Basilisk is the athiest Satan.