Even studio executives have ambition. We should be thankful for it.

One thing that people often say is, "Why does nobody write about work, business, labor, economics, capitalism? Why is it all just affairs and divorces?"

An obvious rejoinder is that actually there are quite a number of novels about the details of various forms of labor, but they tend to be commercial fiction or memoirs. I am a big fan of a writer named Cameron Hawley, who was an executive at something called the Armstrong Cork Corporation. He wrote a number of novels about corporate life—the best of these is Executive Suite, which is about five executives gunning for the top job in their company after their boss drops dead. Another book I enjoy is James Michener's last novel, Recessional, about a doctor who's trying to turn around a failing nursing home.

So there's are no shortage of books about the details of labor, they just tend not to get a lot of critical attention. However, there are even some literary novels that are about money: I really enjoyed Jonathan Dee's The Privileges, which was shortlisted for the Pulitzer in 2011. This book hinges on the murky ethics of a private equity guy.

But I think the real critique is not that there's no books about labor, but that in most books, the characters' jobs seem to play very little role in their emotional lives. For instance, in one of 2024's better books, Rejection, one would be very hard-pressed to remember what any of the characters (other than the tech-bro guy) actually did for a living.

This is somewhat true to life: I honestly have a hard time remembering what most of my friends do for a living, and with good reason—my impression is that most of them just do their work and try not to think about it except when they're at work.

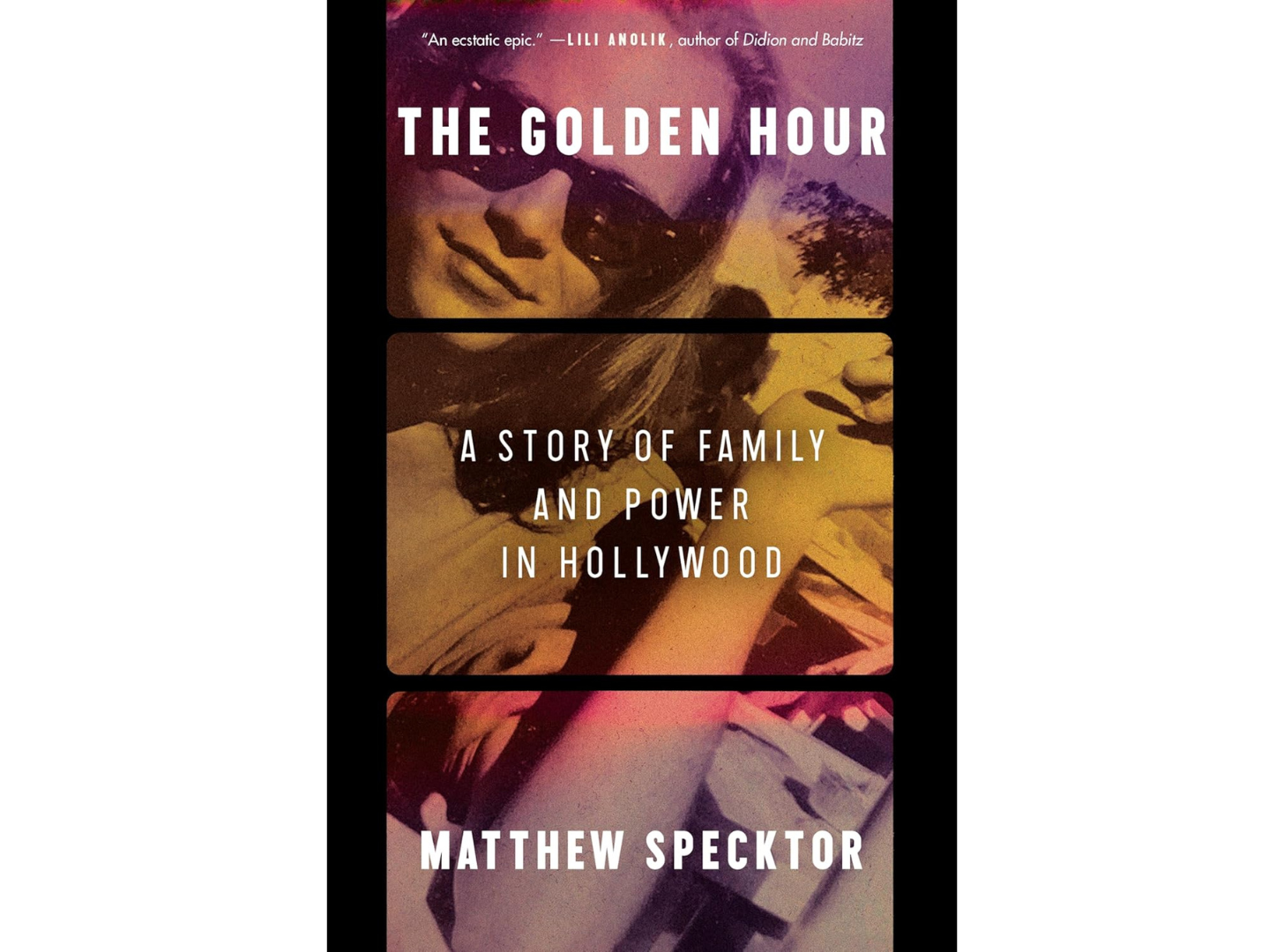

However, there are many people for whom work is at the core of their personality. It seems clear, from reading Matthew Specktor's recently-released memoir The Golden Hour, that his father is one of these people. Throughout the story, the father character, Fred, a Hollywood agent, remains thoroughly opaque. It's not clear if Fred is particularly interested in film-making as an art form. What Fred enjoys is finding clients and making deals.

The action of the book starts in the 1950s, long before Matthew is born, with his father's entrance in the world of Hollywood agenting. In Fred's description, he got into the business because a girl rejected him for not making enough money—she prefers to go with guy who makes enough to take her to a fancy restaurant. Fred asks what this guy does, and she says he's an agent.

At least in Matthew's telling, Fred isn't stupid, but he's not introspective or self-conscious. He decides that he wants to be an agent, and he launches himself into it:

MY FATHER IS to live the rest of his life in a kind of eternal present tense. He is not today, nor will he ever be, an introspective person. Which is not to say he lacks depth. Only that his mind rides the crest of its present moment like a surfer’s, neither looking too far ahead nor sulking upon its history. It’s a quality that will serve him well, but here in the summer of 1956, when he goes to work for MCA, he remains fundamentally green. Do you need talent to enter the motion picture business? Do you need to be able to dance or sing or ride horses? No. Do you need to be overwhelmingly good-looking? Not really. My father is a nice-looking man, but he is handsome in a way that doesn’t spur any double takes on the street. Do you need to be ruthless? Depends on who you ask.

The book proceeds more or less chronologically, sometimes in Fred's perspective, sometimes in the perspective of Matthew's mother—who has her own complicated relationship to the movie industry (she becomes a screenwriter by working as a scab during a writer's guild strike). Eventually Matthew is born, and we start seeing scenes from his teenaged and young-adult perspective as well. Sometimes there are detours, as when the narration inhabits the head of Lew Wasserman, Fred's former boss, or James Baldwin, one of Matthew's college professors.

The book is basically about ambition: Fred’s desire to make a mark on this business. He starts off very small, representing a lot of Black actors in 'race' films. Eventually he starts looking for people who could potentially be stars. His favorite client is Bruce Dern, who he sees through a number of career swings. He briefly represents Jack Nicholson, but can't get anywhere—the actor is too strange, not to the taste of most casting agents, and eventually he and Fred part ways.

There's an incredible rhythm to the book. It occasionally slows down to show a scene, as when Matthew's mother encounters Warren Beatty at a poolside, and the actor is reading the script for Bonnie and Clyde. But generally it doesn't traffic in a lot of anecdotes about stars. It alternates between a kind of high-level overview of the changing business—the appearance of a new set of writers, actors, and directors who create a startlingly different kind of movie that's much grittier and more frank.

This changing of the guard is facilitated by the personal ambitions the younger agents and studio executives as well. One thing you realize, reading this book, is that if young agents and producers are going to make their mark on the industry, then they need to do it by championing a new kind of project. That's how it works. If you're a new agent, you can't get the kinds of clients that everyone wants: you need to find clients that are different and somehow convince people that this difference is going to be the next few thing.

The same happens later when Matthew works as a studio executive. His friend starts championing a book, Fight Club, that seems immediately unsuitable for film:

“Raymond.” I call him back at the end of the day, having read the manuscript at my desk, where I stare now again at its first line. “Buddy, are you insane? ‘Bob had bitch tits.’”

“What’s wrong with bitch tits?”

“Nothing. But this book isn’t a movie. Not in a million years.”

“Sure it is.”

Later, he's surprised when Raymond convinces his bosses to buy the rights:

Raymond is persuasive, but it still surprised me when his company, Fox 2000, optioned the novel several months later. Fight Club seemed unlikely, but then again Fox 2000 was also a furnace in need of fuel. A year and a half ago the division had launched with a clean slate, an entire studio without any movies, and so they were on a buying spree, snapping up rights to novels, short stories, and nonfiction books right and left.

Mixed in with this story is the tale of Matthew's own ambitions, which are distinctly different from his father's. Although Matthew works for a while as a studio executive, he really wants to be a writer. He's just a wildly different person than his father—more invested in the thing itself, in some vision of what stories ought to look like. Where Fred's ambition is merely to make a mark, Matthew wants to make a mark of a specific kind.

Unlike his father, who still works in the industry to this day (he represents Danny Devito, Morgan Freeman, and Pierce Brosnan, among others), Matthew grows somewhat disillusioned with the business, and there's a story here about the slow loss of Hollywood's middle class. For the bulk of the story, through well into Matthew's adulthood, his family isn't particularly well-off. They live a typical middle-class lifestyle, amongst other families for whom Hollywood is just their job, their business, the same as Cameron Hawley's business was the Armstrong Cork Corporation.

But, over time, movie budgets increase and the number of releases goes down. On the agency side, there are fewer deals (hence less need for agents), but the deals are much bigger.

No more middle-class movies. And no more middle-class people either, just riches and poors. When my parents embarked upon their lives in the entertainment business, forty years ago, it was wide open, at least for those who were white and able, and so they were able to tell themselves a story, that the movies were for anyone and everyone, because they felt, they did, like everything was there for the taking....Now that studios have quarantined their output into tentpoles and arthouse pictures, and now that they are making fewer movies annually than they used to, winnowing their slates down every year, that promise is evaporating. What’s left is the cold, dead mechanics of meta-corporate capitalism, a system that will reward the same few people again and again and again.

I highly enjoyed the book and recommend it strongly, with one caveat: I initially found it difficult to get into—When Fred is trying to break into the business, it's not as interesting. But very shortly the book slides into the perspective of Lew Wasserman, Fred's terrifying boss, who is being investigated by the Justice Department for antitrust violations, and I was hooked.

The author narrates the audiobook, and he does a fantastic job. This is one book where audio is a good idea.

The book is so deft in how it mixes together the personal and family and corporate stories. There's so much going on—for instance there's a tale in here of Michael Ovitz brokering the sale of Columbia Pictures to Sony. But it's never too much—the genius of the book really lies in the execution, and the way that no story manages to overpower the rest.

At its core, this is a book about the interplay between personal ambition and creative ambition, and the ways that the personal ambition of the business guys—the agents and studio heads—result in changes to the products that we watch in theaters. Movies like Fight Club get made, in part, because there are studio executives who are desperate to move up in the world. They need to create some kind of stir in order to get attention, so they stake everything on these oddball pictures.

Ultimately, I would say Matthew believes the heroic era in Hollywood's history is over. Because of consolidation, there's less and less room for people like Fred Specktor—scrappy nobodies. Instead you need to be the kind of person who's able to flatter the head of some conglomerate.

But I don't know. We've lived through one boom in our lifetime—the Peak TV era—when all kinds of insane projects got greenlit, and many careers were made on the back of those projects. Mad Men was also acquired by executives who had a crazy-eyed vision to make AMC, of all places, into a destination for original television, and that a well-made, high-quality show would really stand out in the cable television landscape. That show only started airing in 2007—not that long ago. It seems too soon to say that everything is over, shut down, finished.

Matthew is older now. Heck, I feel very old as well. But what comes through in this memoir is the power of personal ambition. It's not that every ambitious person will break in, but it's clear, at least to me, that people who feel shut out will find a way to break down the doors, and some people at least will slip through. Ambition is a kind of living force that pulses through this book, and it's that force which causes pictures to get made.

Afterword

My policy on getting advance reader copies (ARCs) from authors has been wildly erratic, and for this I apologize. Generally I refuse ARCs unless it's for blurbing purposes. I prefer to buy the book, so I won't feel beholden to the author. In this case I accepted an ARC many months ago from Matthew, however I misplaced it at some point because I'm unused to reading paper books. Eventually I purchased ebook and Audible versions, and those are the ones I used for this review.

I should also note that somewhere in this process, Matthew became a friend. I feel somewhat conflicted about reviewing the book, because I usually don't review books by friends, but I grandfathered him in because when I started reading the book I didn't know him. Hopefully that's okay.

Reading-wise, I've been taking it easy, trying to recharge. Now that my Mahabharata and 19th-century American literature projects are both wrapped up, I'm attempting to read widely and let my next obsession find me, without forcing things. However, I've been enjoying doing these reviews of frontlist titles for the past month, and I hope to make these a regular feature of the blog.

Two other notes:

At some point over this weekend, this blog passed eight thousand subscribers! When I started publishing short stories in this newsletter (the first of my tales went live June 20, 2024), I had 771 subscribers. That’s a ten-fold increase in less than a year. Thanks so much for your time and attention.

The Samuel Richardson Prize announcement went live last week! Here’s a link if you missed it: the short version is that the prize is for self-published literary novels (or collections). There is no entry fee and no monetary prize: the only reward is recognition. The contest deadline is July 31.

So, I'm one of those people who wants American literature to be more concerned with work. It's just such a rich topic to explore. Some people make it their whole life and personality, others clock in and out to go about their lives. But I think most people are somewhere in the middle. The most important things to them, personally, are family and friends (and maybe hobbies). But they spend 40+ hours a week a work! They know a ton about their industry and find things to appreciate about it, even if begrudgingly. I thought SEVERANCE by Ling Ma did a great job exploring this. The protagonist wasn't passionate about book binding and international logistics, but the further she got into it, she did become kind of fascinated. And why wouldn't you? It's kind of interesting!

This is something that TV does better than novels, in my opinion. By necessity, most TV shows need a clear premise that a wide number of people will connect to. So this one's about a paper supplier, this one's government workers, this one's ad executives, this one's a restaurant kitchen, etc. And they're all about the human element, but the best ones get to something unique about that particular work setting. But there's no reason a novel couldn't do that! THE BEAR could be a novel.

As a side note, I've had EXECUTIVE SUITE on my to-read list for a while now.

So uplifting, Noami: "It's not that every ambitious person will break in, but it's clear, at least to me, that people who feel shut out will find a way to break down the doors, and some people at least will slip through. Ambition is a kind of living force that pulses through this book, and it's that force which causes pictures to get made."