Books don't cause violence

The Columbia protests have no implications for university curricula

Columbia was trashed in Congress for employing professors that support Hamas and teach about decolonization. Then there were protests at Columbia. Students at Columbia felt threatened by the protests. The police were called. Since the purpose of protesting is to provoke an overreaction by authority, it seems like everyone is getting exactly what they want: protesters show they’re the victims; the authorities show they’re tough on antisemitism.1 But now we get to the final stage, where think-pieces must be written about how this means modern university education is irretrievably broken.

For these protests to count as a social problem, the student protesters must be defined as “violent”. But I think we all know that today's students aren't particularly violent or confrontational. In 1968, Columbia students occupied administration buildings for a week. Students with sticks fought back against the police, and one officer was permanently disabled. Even that wasn't a particularly violent protest. In 1962, when the Ole Miss was being integrated, 28 federal marshals received gunshot wounds and two civilians died.

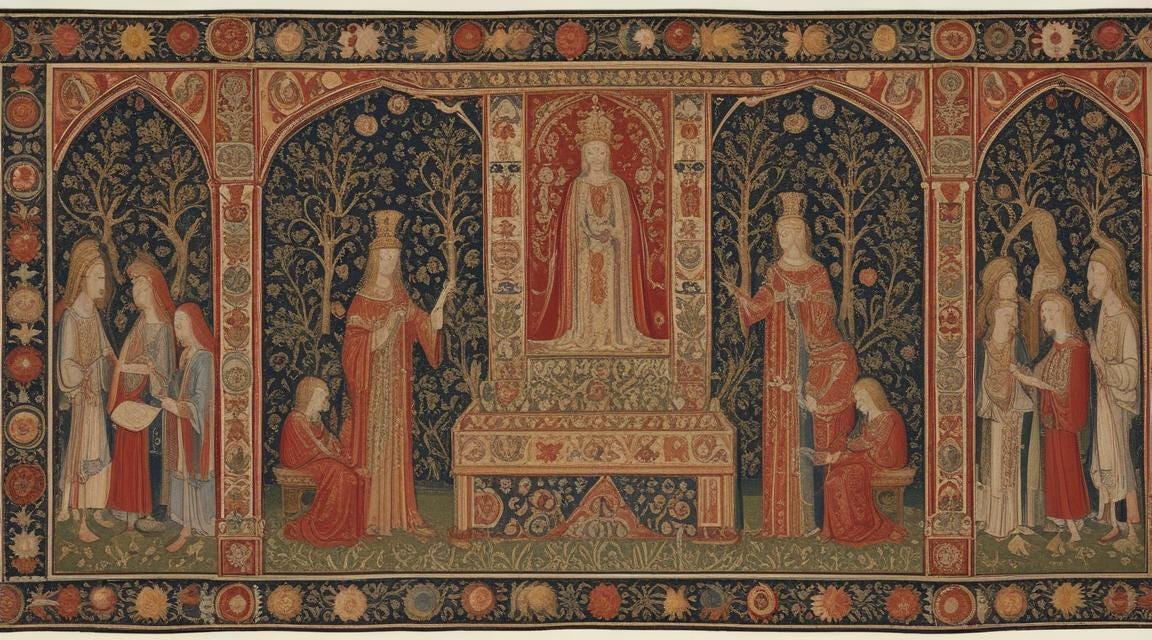

Still, no modern student protest even holds a candle to medieval student behavior. In the 1200s, the students were absolutely out of control. Thirteenth-century Oxford, famously, had a murder rate several times higher than the City of London and sixty times higher than it has today!2

“If I wanted to give advice these days about, well, what could you do to really seriously increase levels of violence in our society?” Eisner said. “Probably I would say, ‘O.K., take a few thousand fourteen-year-olds, just males, out of their context, give them knives and lots of alcohol, and put them into halls—and wait and see.’ ” In the Oxford murders that Eisner has looked at, more than seventy per cent of the victims and the perpetrators were students. Ninety-nine per cent were male. (During the same period, eight per cent of London’s murderers were women.)

Cambridge University was founded in response to the town of Oxford’s attempts to curb the murder rate: when Oxford (the town) hanged three scholars who’d killed a woman, a good portion of Oxford’s students and faculty decamped for Cambridge to set up a school where they’d be subject to even less control.

Other medieval university towns were no better. The students at the University of Paris got so angry in 1229 about the Crown’s attempts to curb their violence that they went on strike for two years! Just up and refused to atend classes, unless they could be exempted from discipline. In Bologna, the violence was similar but different—in that town it got political, with students getting involved in the Guelph v. Ghibelline disputes.

The kids were not alright.

As far as I can tell, this was mostly a medieval phenomenon. During the early modern period, society as a whole became less violent, and the state gained an upper hand. Some of the stress might’ve been relieved by the rise of dueling in the 16th century, which became extremely common and continued right up until the late 19th century.

Notably, there was nothing in the medieval canon or corpus that encouraged violence. Their education in Aristotle and the scholastic philosophers didn’t encourage them to get drunk and go out and rape and murder people. Indeed, they had much stricter ethical norms than today—for instance, not just the students but quite frequently the teachers were supposed to be celibate. Until the mid-19th century, an Oxford don who got married had to give up their post!

Their behavior had absolutely nothing to do with what they were being taught in school, and everything to do with their own youthful hormones and with the society in which they lived—a society with a very weak state and no police force. Today we live in a society that has a much stronger state and students are much older—in medieval times, university students could be as young as 14 and typically stayed three to six years, whereas today most students are between 18 and 22. Not to mention that the presence of women presumably has some leavening effect, since women are less violent overall.

But even more important than the university and its demographics, society is just less violent now. You could reconstruct a medieval university—exact same demographics and curricula—and I highly doubt its students would be killing five or six people a year. That’s just not the society we live in.

These are facts that everyone knows. Except in a few very unique instances (Leopold and Loeb come to mind), crime isn’t a result of ideology. People don’t read a book that says “do crimes” and then go and do crimes. The kids at Columbia can read Frantz Fanon all day, and they’re not gonna engage in violent revolution, because…that’s simply not what kids today do.

Does reading affect behavior? Well, yes. But it does so through the mediating effect of an overall reorganization of society. The kids at Columbia might read Frantz Fanon, go and get jobs as historians, write articles about how medieval Oxford was actually a police-less paradise, and inspire someone else to run for city council, dismantle the police, etc, and then maybe the murder rate would spike (or maybe it wouldn’t). But the intervening steps have to happen first. The mere introduction of certain ideas into students’ head isn’t going to spontaneously create violence. That’s just not how ideas work. The life of the mind occurs on a higher plane than regular life. An ethicist and a physicist are equally likely to cheat on their wife. More amusingly, an avowed intellectual proponent of free love is just as likely to be thoroughly bourgeois and monogamous in their own personal life. People’s interpersonal behavior isn’t really affected by their reading.

To read about a free-love proponent who seems rather touchingly (and monogamously) in love with his wife, see this post on William Godwin:

That’s why I’ve always been careful to avoid the idea that the Great Books will help you live a happier or more fulfilled life. I think the Great Books are invaluable if you want to live the life of the mind. I think if you’re a writer or a thinker, the Great Books are very grounding, because they put you in touch with universal spiritual values.

Which is to say, there are certain values that only make sense in the aesthetic or intellectual realm. For instance, intellectual integrity: the willingness to be honest in assessing your own reactions and to refuse to say anything that you know to be barbarous or stupid. The Great Books embody that integrity: they don’t attempt to make arguments (e.g. the argument that imbibing decolonial ideas will make kids violent) that very clearly and obviously do not make sense. The Great Books teach you that there are lots of things that you can say, but that it’s not worthwhile saying anything that you don’t personally believe to be true.

That kind of integrity really only matters in the intellectual or creative context. It’s not really useful in every-day life, and, what’s more, in every-day life our passions are so strong that we often forget the lessons of the Great Books. If a person out there is able to have integrity when they argue with their spouse, it’s probably not something they learned from reading Plato—it’s more likely something they saw modeled for them by their friends and family. The kind of animal self-control you need to live an honorable life in the world is simply not something you’re going to get from reading books.

The corollary here is: if you aren’t going to be a writer or thinker, do you need the Great Books?

And the answer is…probably not. But they’ll certainly do you no harm.

Elsewhere on the internet:

I had an article in LitHub a week or two ago about how literary novels elide discussion of money. This is the kind of article where people are always like what about this book about a homeless woman or that book about a working-class black guy or this novel about a nanny. Like…sure. There are some literary novels that are about poor people. But money isn’t only important to poor people; it’s important to everyone. And most literary novels aren’t about poor people. The function of only discussing money in certain cases and not in other cases is to create a nether-realm within which we pretend money doesn’t matter. We see this in one of the examples I raised: in Detransition, Baby, we know much more about Reese’s finances than we do about Ames’s. Why? It’s because she’s poor, while he’s within the money-less nether-realm. Again—this comes down to integrity. You guys can raise whatever objections you’d like, and they might sound perfectly reasonable, but…you know in your hearts that I’m right.

I do in fact think that these protests are antisemitic. Maybe it’s because I’m not Christian, Jewish, or Muslim, but it’s clear to me that Muslims and Christians have a kind of pathology where it comes to Jews, such that Jewish people and (by extension) the only Jewish state, take up a disproportionately large part of their psychic energy. I think what Israel is doing is wrong, but it is something they are doing. America isn’t doing it, and our government doesn’t support their actions. The link between Columbia and Gaza is so tenuous as to be laughable. The Chinese are attempting to wipe out the Uyghur cultural identity, and I’m sure Columbia has plenty of Chinese donors and plenty of partnerships with China, but there’s no outcry on their behalf.

This article notes that medieval Oxford’s murder rate was equivalent to New Orleans. That’s no longer true, with the recent drop in murder rates, the rate in New Orleans (40 per 100,000) is about half what it was in medieval Oxford (70 per 100,000). In contrast, the rate in SF, where I live, is about 6.7 per 100,000.

Fascinating post! Great contextualization of "student violence." I just wrote about the long-term decline in the English murder rate yesterday in a post on Renaissance revenge tragedy, but came to almost the opposite conclusion: that the theater really was enmeshed with certain kinds of violent behavior. It's not that books cause violence (or anything else, mostly) in any simple sense, but that they're a component of culture and in that sense part of the history of behavior or action. Dueling is a good example because it's highly codified and that codification is disseminated in part through literature. I bet if you looked at depositions in some of those Oxford cases, you'd find quite a few cases where homicides were provoked by highly cliched insults or stylized questions of honor. (But probably not, as you point out, by the curriculum itself!)

Hamas v. The legitimate government of Israel.

Just because two people are fighting does not mean either of them are right.