Academic concepts run amok

On "race" and "the self"

For years I was perplexed by the idea that race was invented by the Enlightenment. I had two ways of understanding this concept. The first was obviously true and yet trivial (race, as a biological concept, did not exist before modern ideas regarding biological inheritance). The second was provocative but obviously false (before the invention of race, people did not essentialize the differences between folks who lived in different places). The latter was obviously false because we can see, throughout literature, folks saying “These other people are essentially different from us.” For instance, in Aristotle’s rather garbled half-baked attempt to justify slavery in The Politics he writes that some say only barbarians can be slaves:

They are driven, in effect, to admit that there are some who are everywhere slaves, and others who are everywhere free. The same line of thought is followed in regard to good birth. Greeks regard themselves as well born not only in their own country, but absolutely and in all places; but they regard barbarians as well born only in their own country—thus assuming that there is one sort of good birth and freedom which is absolute, and another which is only relative.

How is this not racism? These Greeks thought that noble Greeks as a category (noble people from Greek cities, wherever those cities happened to be) were unsuited to slavery, while all other peoples, including noble barbarians, could be enslaved freely when outside their cities.

It seems trivial to point out that this is not precisely the same thing as race. Today we would regard a Greek and a Macedonian and a Thracian as being essentially the same race, but to the Greeks the latter two would be barbarians. And yet this is something we already knew! Nobody thought the races were the same in Ancient times, just like we don’t think that, say, Japanese people hold to the same racial schemas that we do in America.

I don’t think the idea “Race was invented by the Enlightenment” is a false or trivial idea. But it takes effort to excavate what’s really meant and what ramifications it possesses. After the spread of the monotheisms, but before the invention of race, the cross-cutting distinction between peoples was religious. In Christendom, only non-Christians could be enslaved, and it was accepted that pagan peoples were not accorded the same rights as Christians, hence the relentless crusading against pagan peoples of Eastern Europe and the Baltic which eventually drove conversion just to get all these knights off their backs, if for no other reason.

Below the level of religion, there was the concept of citizenship—aliens were suspect in many places, at many times. For instance, during Wat Tyler’s revolt in 1381, the people of London killed a bunch of Flemish weavers, for the same reason locals might kill outsiders in every time and place. The same sort of incident is recorded in the Bible, where the inhabitants of Gilead after a battle target the Ephraimites, by asking them to pronounce the word “shibboleth”. If you pronounced it with an initial ‘s’ instead of a ‘sh’ sound, you were an Ephraimite and hence slaughtered. These people were so similar they spoke the same language and had the same religion, and yet instead of taking parole from the survivors, they were slaughtered to a man.

Race, as a concept, came between the level of citizenship and the level of religion. In reading the history of colonialism, we can see how race made colonial domination possible. Take, for instance, the Ashanti Empire. The Ashanti were a well-organized state with a strong military. They defeated the British in several wars. This was possible because the Ashante were allied with the Dutch, who sold them weapons, which they in turn copied and reproduced themselves. The British were allied with the Fante, who harried the Dutch. The Ashante ultimately lost because the British did a deal with the Dutch where the Dutch left the area. Without access to foreign trade, the Ashante were stuck with old guns and old designs for guns and with limited stocks of gunpowder. Thus they were increasingly outgunned. In one war, they were reduced to using cowry shells for ammo (they were useless) or using half the requisite gunpowder (their shells would hit the British and simply fall down, not piercing the skin). Now, why did the British do a deal with the Dutch? Why didn't the Ashante do a deal with the Fante instead? In this case there were specific geopolitical reasons behind it, but if you look at enough of these situations in aggregate, it becomes clear that racism was involved. To the Ashante, the Fante were their main enemy. But the Dutch viewed things differently, they had less issues "losing" to the British. There was a level of solidarity between the British and the Dutch that non-white people did not have.

And if you look at areas where native peoples were able to remain independent, versus where they were subjugated, you often see that independence was only possible when native peoples could play various groups of Europeans off against each other. For instance, the ruler of the Sotho, King Moshoeshoe, supported the British against settlers of Dutch descent (Afrikaners), and as a result Lesotho remained independent of South Africa. But even then, the British often eventually sold out their allies! When the British left South Africa, they very specifically did not do it on the terms under which they left Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Instead of instituting free parliaments, which they could have done because they had the whip hand after winning the Boer Wars, they instead handed the keys to the white people instead, writing acts of incorporation that gave the vote only to white people (with limited representation for the colored people of Cape Colony) instead. Why did they sell out their various allies in South Africa and reward their enemies instead? Racism.

Seen in this way, the invention of race becomes a startling and fascinating development. Race becomes one of the key social technologies that enables white domination. Because of race, wherever white people meet, anywhere in the world, they are able to cooperate against non-white people (a la the way British and Afrikaner people, while despising each other, implicitly cooperated against Black South Africans).

But understanding and explaining this concept is difficult. And I think the problem is that we either view human nature as immutable or too mutable. And the truth is, human nature is not terribly mutable, but the same human tendencies can be channeled in different ways.

So the tendency that makes Greek people more willing to enslave barbarians is, perhaps, the same tendency that makes Dutch and British people willing to cooperate against Black people--but because the tendency is the same, we ignore how amazing it is that the Dutch and British, who are historical enemies (from as long ago as 1381, if you regard Flemish people as being Dutch, or even longer, if you recognize that the invading Saxons actually came from the Netherlands) are able to cooperate because they recognize Black people as being more different. Human nature is the same, but the social institutions it gives rise to are very different.

But for you and I as human beings, most academic concepts are only relevant to us if they pertain to human nature. Unless we study it, we really don't care how or why the disparate groups of white people in South Africa were able to cooperate against all the Black people (who were disunited to the point that some Black chieftains used their tribal police forces to support the apartheid regime!) We only care about this concept if we somehow imagine that the people of the past were less hate-filled than we are. Which is the opposite of true. The truth is that British and Dutch people ought to dislike each other as much as Greek and Thracian people did! And the fact that they don't is only due to racism!

This is something I thought about in relation to the "did pre-modern people have selves" post. Because I think what's different about modern versus pre-modern people is that to pre-modern people there were a lot of psychic phenomena that they regarded as exterior to themselves--as the product of fate or spirits or magic--whereas we regard those same phenomena as interior--as a product of our biology or psychology or personal experiences.

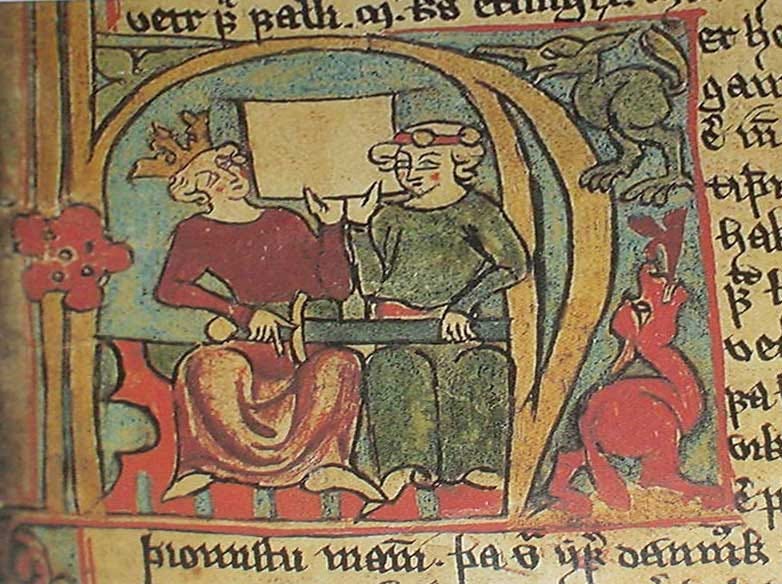

Which on the one hand seems rather trivial, doesn't it? Take the Saga of Grettir the Strong. From an early age he is impetuous, always killing people when he shouldn't and picking fights he ought not. But his true downfall comes at the midpoint of the saga, when he is fighting a spirit, Glam, who curses him, saying from now on his strength will not grow, and from now on he will be afraid of the dark. After that, his impetuousness and cruelty grow, and he takes bigger risks, trusts more foolishly, and is eventually killed.

On some level, the curse is unnecessary to the story. From our modern perspective, it is overdetermined. We can see just from the way he acts, for instance by taking in a slave and then abusing and slandering him, that he is cruising for a bruising.

But there is also a deeper question of causality here: all Viking sagas are about people doing reckless and violent things. Sometimes they get away with it and sometimes they don't, and why is that? For instance, in another Viking saga, the Saga of the Sworn Brothers, the one brother, Thorgeir, is a fucking psychopath. The saga is like, this guy is afraid of nothing. He feels nothing even when his dad dies:

News of Havar’s death spread quickly, yet when Thorgeir learned that his father had been slain he showed no reaction. His face did not redden because no anger ran through his skin. Nor did he grow pale because his breast stored no rage. Nor did he become blue because no anger flowed through his bones. In fact, he showed no response whatsoever to the news – for his heart was not like the crop of a bird, nor was it so full of blood that it shook with fear. It had been hardened in the Almighty Maker’s forge to dare anything

The saga writer is like this guy is a motherfucking killer. And he comes to a bad end.

But the other sworn brother, Thormod, goes to avenge Thorgeir, and he is psycho too! He goes to Greenland and avenges the main killer. Then he kills some other people. Then he is hiding out waiting for a boat home, and he gets bored and decides to run out quick and kill a bunch more people too! That is insanely reckless, why does he get away with it when Grettir doesn't?

Well, I think in pre-modern stories, the assumption is that heroes are going to get away with stuff. So what's notable is when they don't. In Grettir's case, he's been so strong and brave up to now that you need the curse to explain why his luck runs out (the concept of luck is very big with Icelanders, there is no trait more prized than good luck).

Take for instance the most famous moment of the Iliad, when Hector, faced with Achilles at the end, turns tail and runs. As he runs, the Gods debate whether to save him: Apollo gives wings to his feet and Zeus begs for his life, but Athena holds firm in her anger against Troy. And ultimately the scales of fate come out against him:

But once they reached the springs for the fourth time, then Father Zeus held out his sacred golden scales: in them he placed two fates of death that lays men low— one for Achilles, one for Hector breaker of horses— and gripping the beam mid-haft the Father raised it high and down went Hector’s day of doom, dragging him down to the strong House of Death—and god Apollo left him. Athena rushed to Achilles, her bright eyes gleaming, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, winging orders now: “At last our hopes run high, my brilliant Achilles— Father Zeus must love you— we’ll sweep great glory back to Achaea’s fleet, we’ll kill this Hector, mad as he is for battle!

In modern times, we might say, "Achilles was the greatest warrior of all time. Hector ran, he was weaker and afraid, he was doomed to die." But even in those times, the greatest strength didn't always win: Polyphemus didn't defeat Odysseus, for instance. No, the winner was the person selected by fate--the most beloved of the Gods. There was no explaining it. Hector was the superior of Achilles in many ways, but the Gods simply weren't with him on that day.

That's what it means to not have a self. Because our selfhood is a way of taking charge of fate, of assimilating some of these contradictions. In our modern stories, if the superior man doesn't win, then we are uniquely troubled by the tale. And that wasn't necessarily a difficulty to the reader or listener of a pre-modern tale.

But what does it mean in practical terms to believe in the externality of some of these forces, whether you call them character or fate or luck? Well it means in practice that you spend a lot of time on rituals, a lot of time trying to propitiate the Gods. It also means in practice that you believe in action over thought.

So, for instance, in the Saga of Havard, when Havard's son is killed, the man takes to his bed for three years. He is, to our eyes, clearly depressed. And in modern times, we would say, this guy's problem is his depression. He's gotta stop being depressed. The problem is internal to him. But in the saga, his difficulty is solved by him taking revenge on his son's killer! After that, he lives a good and long and happy life! His problem was external rather than internal. That is why there are few epiphanies and few internal monologues in pre-modern tales.

In some ways, it's a much more honest perspective on the world. Who cares about thoughts and feelings? What do they matter? What matters is actions!

And to the extent that thoughts and feelings do matter, they can be externalized: you can offer up prayers or sacrifices or engage in rituals--you alter the thought, hopefully, by engaging in an external practice.

Of course this only works if you genuinely believe in external magical forces that might listen to you! That's why it's so absurd when secular people say "We need ritual in our modern lives." No, we don't need empty rituals: we need rituals that work. Our "ritual that works" is therapy. I have a friend who is a therapist who is dealing with some negative feelings, and I said to her, "It must be hard to deal with this, since you know there's ultimately no way to escape grief." She was like, yeah it gives me more sympathy with my clients. For us, therapy is the ritual. If you feel bad, you go to therapy and eventually time passes and you feel better. It gives us hope that the future will be better than the past and lets us get through our days (somewhat similar to desiring revenge--the reason Havard gets so depressed is that he is old and cannot realistically expect to take revenge, and I think that's why, by extension, there is less depression in old stories--they always believe there is someone they can propitiate or kill to solve their problem).

But, as with ‘race’, I am not sure that ‘un-selved’ living on a practical day-to-day level looks that different than modern life! Maybe in part this is because I come from a polytheist background, where there is plenty of propitiation of spirits and plenty of focus on fate (the core of Hinduism is dharma, which is just literally the stuff you’re supposed to be doing). These are concepts that are readily comprehensible to a modern person, just as, I believe, the idea of a self would be readily comprehensible to a pre-modern person. If we told the writer of The Saga of the Sworn Brothers that Thorgeir actually feels no remorse or fear or sorrow because he is a form of person, a psychopath, that can’t feel remorse or fear or sorrow, he would probably say “Yes…isn’t that basically what I already said about him? We aren’t dumb, we know some people are psycho.” And yet the writer of the saga would, I think, persist in believing that fundamentally fate and the Almighty made Thorgeir that way, while we would persist in believing it was due to his unique neurology. And those differing beliefs would lead us to tell the story in different ways and focus on different details, and, on a deeper level, to have different ideas about the worth of Thorgeir’s life (the saga writer is impressed that Thorgeir is so brave and unfeeling! Whereas we would probably say the story is really about Thormod, the loyal one.)1

All of this is coming to the fore, of course, because right after writing my post about how pre-modern people had selves, I realized that the Indian (but actually Viking) people in my fantasy novel don’t have selves in exactly the way the Icelanders didn’t have them. So I guess I was a little bit wrong in my previous post, okay!

Addenda:

Yesterday I hit 400 subscribers!

I am feeling really good about eschewing culture-war stuff for now. They’re an easy way of getting attention, but they were poisoning my intellect.

I have finished all the easily findable Icelander family sagas (the realist novels of Icelandic medieval literature) and am now reading their legendary sagas and romances. I just finished the Saga of King Hrolf, which is about a legendary Danish monarch and contains fascinating similarities to Beowulf. It’s amazing how much is preserved in the oral tradition: the Jutes who invaded England were essentially Danes, and Old English and Old Norse are quite similar. But all Old English literature was written in roughly the year 1000, while medieval Icelandic literature is from the year 1250 to 1500. So there is a wide variation there, and yet the same cultural memory was preserved in both cultures.

It made me wonder how old some of our other folk tales are. Apparently very old! A good number of them date back 4,000 years, to when our ancestors were just wandering around on the steppe, building kurgans and shit. Some folks say though that the oldest oral tradition is that maintained by the native peoples of Australia, who may have a story that is forty thousand years old!

The sworn brothers swear eternal friendship, but they actually end up parting relatively early in the story. It happens in the following way:

People say that at the height of their tyranny, Thorgeir spoke these words to Thormod: ‘Do you know of any other two men as eager as we or as brave, or indeed anyone who has stood the test of his valour so often?’

Thormod replied, ‘Such men could be found, if they were looked for, who are no lesser men than us.’

Thorgeir said, ‘Which of us do you think would win if we confronted each other?’

Thormod answered, ‘I don’t know, but I do know that this question of yours will divide us and end our companionship. We cannot stay together.’

Thorgeir said, ‘I wasn’t really speaking my mind – saying that I wanted us to fight each other.’

Thormod said, ‘It came into your mind as you spoke it and we shall go our separate ways.""

Thormod loves his friend, but he also knows that Thorgeir is straight up psycho and will eventually pick a fight just to see who would win, so he makes sure they part while they are still friends, and they never see each other again. This shows what we would call a clear psychological acuity, and it’s worth noting that there is no appeal here to either external or interior forces. Everyone knows that it is simply in Thorgeir’s character to act this way (the moment Thormod says it, the reader goes Oh right, of course that’s true. I know people like that) but there is no speculation as to how or why he is made this way.

I think you're underrating the "race was invented by the Enlightenment" historiography. [edit: nope! I didn't read the post carefully. But I'll leave my folly here intact.]

Broadly speaking, historians agree that most societies had ways of talking about "us" and "them". Often two kinds of "them", in fact: the "them" who were nearby and routinely interacted with and the "them" who were faraway strangers, almost more an idea than a materially concrete reality. You can abstract those ways of making distinction to a human universal, but I'm not sure you learn much in the process.

When you dig into the particulars, what you find are profound variations in the following:

a) Intensity of the us/them distinction--intensity in terms of sociopolitical institutions that enforce or are founded in the distinction, intensity of generalized feeling about the distinction, intensity of cultural representation focused on the distinction

b) Distribution of the us/them distinction. In many pre-modern agrarian societies, markedly 'different' people were rarely encountered or thought about in many communities; the people who had to care were merchants, government authorities, sovereigns and their courts, intellectuals or scribes, etc. The residents of cities and large settlements were typically more aware of us/them distinctions, but they also were often more indifferent to them/more composed of multiple communities of people that spanned such distinctions.

c) Fundamental basis for an us/them distinction: is it geographical? Linguistic? Spiritual/cultural/philosophical? Embodied? (Here what we think of race in physiognomic terms isn't the only way that people in history make embodied distinctions: another major 'language' of physiognomic distinction involves body modification and clothing--"us" scarifies or modifies in a particular way, "they" in another, etc.) Is it simply kinship? ("We" are of one lineage, with one totem; "they" another).

d) Mutability of us/them. How hard is it for "they" to become "us", and vice-versa. In a lot of world history, us/them distinctions are extremely fluid. You learn a language, you become part of the "us"; you marry into a society and live with your spouse's kin, you're "us" in every sense that matters. You're exiled from your home community? You're "them" now, even if yesterday you were completely "us". Convert to our religion? You're part of a global "us" but local "they" might still apply, depending.

e) Maintenance of us/them distinctions within a bounded culture--e.g., that within a big "us", there are smaller us/them divides that are as sharply drawn (or more sharply drawn) than the 'big' divisions. Caste in South Asia in caste-organized regions arguably mattered more than the dividing lines between people speaking Hindi, Urdu, Burmese or Malay, at least in some cases.

When people talk about "the Enlightenment invented race", therefore, they're talking about the extremely particular kind of us/them it represented along these sorts of lines. An idea of us/them that was increasingly biologized and essentialized--seen as fundamental, biologically and materially real, and immutable, a comprehensive universal principle that applied to all of humanity. An idea of us/them that was intensely instrumentalized in sociopolitical systems--used to organize political power, to justify military conquest and imperial rule, to structure economic hierarchy. An idea of us/them that was ubiquitously present in Western societies--where even people in communities that were incredibly remote from "them" were exposed constantly to culture and ideology that represented the us/them of race. And this happened quickly, which is why it's attributed to the era of the Enlightenment. Early modern European ideas about us/them differences were much more heterodox and negotiable.

Just to give an example of the difference that "race" in this sense made:

Circa 1550, Portuguese expeditions to Senegambia in West Africa and Kongo in Central Africa approached negotiating with local rulers and societies for trade goods (including slaves, but not predominantly so) roughly the way they approached trading and negotiating in the Mediterranean world. If you could get away with raiding, you did, but generally building a longer-term relationship was better. Captains, sailors and representatives of the Portuguese crown and the Catholic Church wanted to learn local languages and cultures to facilitate trading. Portuguese merchants who stayed in trading posts often intermarried without any worry or concern. They didn't think in terms of "race" in the Enlightenment sense even if they saw their Senegambian and Kongolese counterparts as a "them".

Circa 1796, the Scottish traveller Mungo Park went by himself up the Gambia River to the upper Senegal R. basin and then across to the upper Niger River. His best-selling account took the humanity and complexity of the societies he engaged for granted--and during his travels, he was also briefly enslaved as well as held captive, which he used for a kind of sentimental, generalized understanding of the consequences of the Atlantic slave trade for those taken to the Americas. And yet, the intensification of that trade had also increasingly "racialized" slavery--e.g., had defined an incredibly severe and destructive form of involuntary servility as being necessarily something that could only be visited upon a particular group of people who were defined not just geographically but in more and more essentialized ways. So Park was showing that "race" wasn't fully formed in the modern sense, but the whole situation showed that it was nearly so.

Circa 1880, as the "scramble for Africa" unfolded, British, French, Belgian, German and Belgian authorities engaged in military conquest and then imperial administration in West and Central Africa generally viewed Africans as a universal kind of "them" who were at the bottom of a comprehensive universal hierarchy of "thems". They'd completely erased any memory of an era where Europeans in West and Central Africa related to different societies within those regions on a more or less equal footing, making fine-grained distinctions between those societies. Those administrators saw the African "them" as immutably inferior based on a pseudo-scientific sense of biology, they generally derogated the idea that the language, culture and history of "they" was worth knowing--or even that it meaningfully existed at all. They organized political structures premised on the maintenance of hierarchies where race was the most important premise of those hierarchies and often refused to acknowledge when one of "them" demonstrated training, competency and capability that was indistinguishable from "us". At the same time, Western audiences who would never visit or directly contact West and Central Africa were showered with popular culture that portrayed those places in line with the concept of race being applied to them; the us/them distinction in race was disseminated widely and comprehensively via mass media.

So if you want to claim that because all past societies had "us/them" distinctions, the Enlightenment didn't invent race, you're building a strawman that's trivially easy to knock down. Modern race is an incredibly particular and highly consequential configuration of us/them--imagined as immutable and essential, embodied and cultural, universal and comprehensive, disseminated across global societies (including to "them"), used as the central underpinning of sociopolitical systems that gated access to political and economic power, and so on.

Compare this to classical Greek thinking about "barbarians". For the really far-away barbarians, Greek opinions OF barbarians mattered not one bit. It had no impact on their thinking, and had no authority over them. For Greeks engaged in trade in the Mediterranean, there was no particular chauvinism about who they would deal with. Greeks in antiquity were perfectly capable of modifying who was a barbarian if the idea became an inconvenient obstacle to their own political and economic activity, or if their conception of the scope of the Greek world expanded. Hellenism demonstrated that the Greek conception of non-Greeks was fluid in ways that modern race in its most intense heyday was not. The Greeks made distinctions between "thems" that were barbarians (mostly based on geographic distance and therefore lack of concrete knowledge) and the "thems" who were familiar (most notably the Romans). etc.

On race, I noticed in researching textile history that in the early years of encounter between, say, Europeans and Africans, there is a sense of difference that might justify conquest but not what I would call racism, which implies a hierarchy of superiority and inferiority. Early on, Europeans describe West African dignitaries as kings as wearing draped cloths like Roman togas. These Europeans admired the Romans and respected kings, although they would have no scruples about making war on people if they wanted their territory. There is a sense of difference that doesn't imply that, except insofar as Christianity is the One True Faith, European civilization is superior, let alone that a given white person is superior to a given black one. Indeed, an African king would presumably be superior to a European servant. At some point, that changes. Although I'm entirely pro-Enlightenment, I find it plausible that in trying to square self-interested conquest with Enlightenment individualism Europeans started cooking up racial hierarchies. As for the Dutch and the English, it's interesting to think about how things might have been different if, instead of the Dutch, the Spanish or French were involved. Although the Dutch and the English did fight the occasional war, they were hardly sworn enemies. The Glorious Revolution was essentially a Dutch takeover of the monarchy.