A writer only has one ethical responsibility

To do no harm to literature itself

Most of my views about the ethical responsibility of the writer are utterly idiosyncratic and, as far as I can tell, are shared by none of my writerly peers.1 One of those views is that a writers’ main ethical obligation is to the integrity of literature and language itself.

This obligation is separate from the obligation to write as well as you can. The work of the writer is separate, I think from their ethical role as a public figure and steward of the world of letters. I assume that a writer in their work is producing only the work they’re capable of producing, and that they are unable, psychologically or ethically, to alter the work in its finer details, no matter the political consequences. So, although the work might be honest or dishonest, intelligent or unintelligent, beautiful or ugly, I don’t think ethics really come into play when you sit down to write.

Ethics only matter when it comes to what the writer does outside their work: their public statements, their critical ephemera (reviews, prefaces, etc), their tweets, their teaching, their organizing activity. To the extent that they have power in the world, how do they use that power?

This means I don’t think unsuccessful writers have any particular ethical responsibilities outside those as human beings as citizens. It’s only to the extent that you’re successful that you have particular ethical responsibilities as a writer.

To me, the number one ethical responsibility a writer has is not to shit the bed. Don’t befoul the world of literature.

Which is to say, don’t say things about literature that are absurd or that make life more difficult for other people.

Take Viet Nguyen’s op-ed a few years ago in the New York Times, where he writes:

“Diversity” itself, unless it occurs at every level of an industry, and unless it meaningfully changes an aesthetic practice, is a fairly empty form of politics.

To me, this statement is a pretty comprehensive shitting of the bed. The idea behind diversity is that a more demographically diverse artistic world will diversity the aesthetic practice of the artistic world. But here Nguyen outright suggests that diversity is not enough: art also needs to be more explicitly political, and that if diversity doesn’t accomplish this aim, it has failed. This position fundamentally undermines the creative freedom artists need to create. We ought to operate from a position of generosity: artists are creating what they are able to create. To demand anything other than peoples’ best is a violation of our ethical responsibility as artists.

He goes on to write:

And here, marginalized writers who tell stories about marginalized populations do not get a pass. Take immigrant literature. During the xenophobic Trump years, when immigrants and refugees were demonized, simply standing up for immigrants became a politically worthwhile cause. But so much of immigrant literature, despite bringing attention to the racial, cultural and economic difficulties that immigrants face, also ultimately affirms an American dream that is sometimes lofty and aspirational, and at other times a mask for the structural inequities of a settler colonial state.

Many immigrants’ experience of America is of genuine economic and political freedom. To demand that their experience be censored in art is a violation of our ethic as a writer. You can say they’re wrong, or that it doesn’t resonate with you, but to argue that it shouldn’t be written at all, or that they are hurting literature—that, to me, is shitting the bed.

When a writer is successful I judge them primarily on this question: in their public statements, are they improving the world of letters? Or are they hurting it? That’s my main problem with Craft In The Real World, it hurts the world of letters—it argues that we cannot understand each other, and it destroys the conditions under which all people, but especially PoC, are allowed to create. Similarly, anyone who buys into these ideas is hurting literature.

A friend told me about being in a workshop recently, hosted by a well-known white writer who isn’t known for being political. The workshop leapt on one of the participants, with every single participant calling his story misogynist. But it wasn’t that misogynist. And to the extent it was, that was due to the PoV character’s point of view. There is no possible way that this talented workshop leader didn’t know this, but they said nothing. That, to me, is hurting literature.

Writers who try to restrict other peoples’ creative freedom are hurting literature. Similarly, when they extol work they know isn’t good, that’s hurting literature. This is the same standard by which I judge conservative writers—if you support legislative efforts against “wokeness”, you’re hurting literature.

I’m thinking of all this in relation to the recent article about Merve Emre. I’ve since learned more about the complaints against her, and they seem to amount to: her work is overrated. But I don’t demand that writers’ work measure up to their public reputation—a writer doesn’t determine their own public reputation. What I ask is that a writer not abuse that reputation. And Merve Emre creates more freedom for other writers. She champions formal and structural beauty in an era when a lot of critics have forgotten how to talk about those things—she doesn’t sign on to trendy causes. She extols weird European writers who aren’t even unpopular enough to be cool, just because she likes them! I think that’s great. She is doing her job.

Similarly, a lot of the knocks against Ralph Ellison, as a public figure, were that he didn’t help other Black writers (allegedly, he was a very jealous person). But I think in his example, as a Black writer who sought the space to create on his own terms, without being hemmed in by race, he actually created much more freedom for the other Black writers who came after him.

You can see this carefulness even in a lot of literatures’ bete noirs. Like take Edward Said: he critiqued the canon in terms of its politics, but he never said it was bad or poorly written. He created a method of reading that he thought could rehabilitate and enliven the canon. Although his work has been used poorly, he could’ve done much worse if he’d said, “Therefore, we ought not to read Jane Austen.” Instead he wrote,

It would be silly to expect Jane Austen to treat slavery with anything like the passion of an abolitionist or a newly liberated slave. Yet what I have called the rhetoric of blame, so often now employed by subaltern, minority, or disadvantaged voices, attacks her, and others like her, retrospectively, for being white, privileged, insensitive, complicit. Yes, Austen belonged to a slave-owning society, but do we therefore jettison her novels as so many trivial exercises in aesthetic frumpery? Not at all, I would argue, if we take seriously our intellectual and interpretative vocation to make connections, to deal with as much of the evidence as possible, fully and actually, to read what is there or not there, above all, to see complementarity and interdependence instead of isolated, venerated, or formalized experience that excludes and forbids the hybridizing intrusions of human history.

Said, Edward W.. Culture and Imperialism (p. 96). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

A writer might be conservative, might be transphobic, might be a terrible abuser or all-round awful person, but if they don’t do harm to literature as a whole, then I think they’ve fulfilled their ethical responsibility as a writer. For instance, no decent writer would act as a sensitivity reader or call on a book to be banned or withdrawn from print. A decent writer is even careful in saying “This never should’ve been published” or “This is harmful”, because a decent writer would rather let a hundred terrible writers be published than risk harming one good one, because a decent writer knows that most work that gets published is terrible—there’ll always be terrible work. What is hard is for anything good to get published in the first place.2

Decent writers are also distrustful of authority: they know that agents, editors, publishers, awards committees, program directors, all sometimes get it wrong, and although gatekeeping is unavoidable (and probablybnecessary to the maintenance of high culture), they also maintain a skepticism about the taste of the gatekeepers. No decent writer would support a Soviet-style Writer’s Union or any other form of monopoly on who gets to decide what is expressed.

Most decent writers, I’d argue, can’t help behaving ethically in their public positions.3 If there is anything that a decent writer knows, it’s the conditions required to create decent literature, and to argue against those conditions (even when it is in service of more economic or political equality), by placing restrictions on the imagination or on what we can read, is a profound act of nihilism: it’s to say, this thing, the thing that I know best, is worthless, and I want to destroy the conditions that allowed me to work. Only a very, very few decent artists have fallen into that kind of nihilism (which is why it’s hard to find, say, a decent Soviet writer who supported Stalin, and why the example of the few who did, like Konstantin Fedin, are so horrifying).

Indeed, many otherwise apolitical Soviet writers seemed driven into a dissident status they might’ve otherwise avoided. Osip Mandelstam, for instance, almost seemed to have a death-urge: the poem that got him sentenced to the gulag is utterly unlike the ones he normally wrote, and it’s unambiguous in its disdain for Stalin. If he hadn’t recited that poem, he could’ve lived! Anna Akhmatova, in contrast, avoided direct expression of dissidence, and she lived.4 Perhaps it is idealistic of me, but I think there are certain sorts of regimes that no decent writer can avoid opposing (in their hearts, if nowhere else).

But when it comes to short-term reputations, many writers are extremely overrated: they’re not decent writers, and it’s not clear if they are really in touch with the wellspring of the imagination. And that’s okay, it’s not their fault. I assume they would write well if they could. But because they don’t understand where literature comes from, they don’t know how to nurture that place. So when I see a writer who is highly acclaimed, it’s just a pleasure when they’re a friend of literature rather than its foe.

And yes, the ethics I am propounding basically amounts to an ideology about the conditions necessary to create great literature. But my experience is that decent writers believe in this ideology. Some ideologies simply have the facts to ground them. Literature comes from communion with something unknown and mysterious, and any decent writer seeks to widen, rather than foreclose, the aperture through which literature enters the human consciousness.

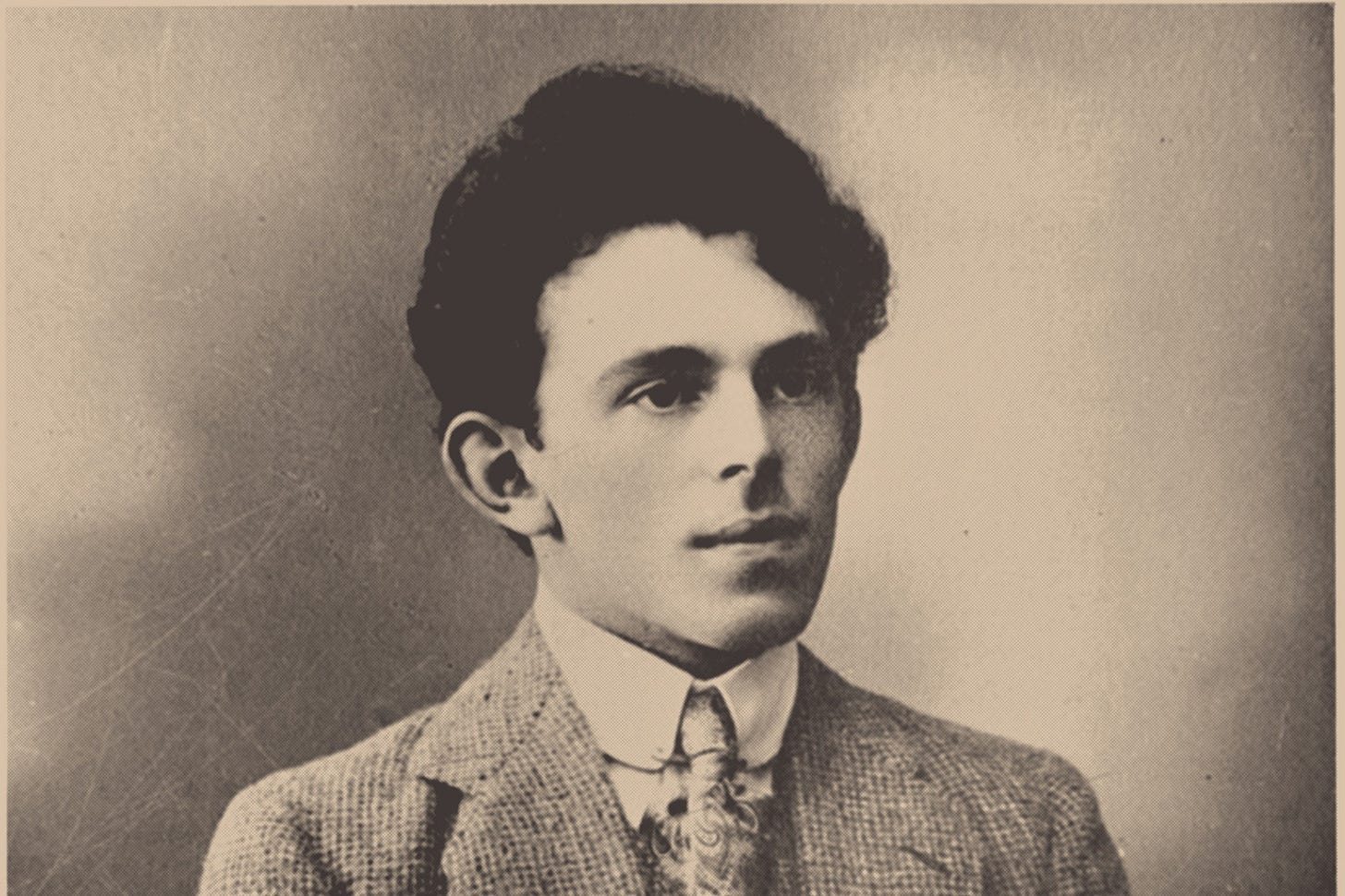

Oh my god, Osip, what a cutie

For instance, I think that diasporic writers, like myself, shouldn’t be worried about white writers appropriating our culture—we should be more worried about appointing ourselves as spokespeople for the homeland! It’s kinda whack that the thirty million Diasporic Indians have more influence on worldwide perceptionb of India than do the 1.7 billion people of India.

I do think saying “This should not have been published” or “You should cancel this book deal” is free speech. I just think that if you’re a decent writer, then those calls must be on the grounds that the book is harmful to literature as a whole, not merely that it’s a bad book or contains bad opinions. And I think very few books are actually harmful to literature as a whole. Most books, even the worst, are swallowed up by the abyss, and often the controversy they engender is more harmful to the world of letters than the book itself ever could’ve been. I think a decent writer has faith that good literature will win out in the long run, and that people with taste can differentiate between the good and the bad. A decent writer is more concerned with creating maximal freedom for themselves than they are with reducing it for others, and any decent writer would worry about saying things publicly that might hem in their own freedom later on.

By “decent” I don’t mean virtuous, I just mean “better than average at writing”.

Though admittedly it was easier for women to survive, and the Great Terror was random enough that there was no guaranteed way to live, so perhaps Mandelstam simply despaired of surviving and decided to commit a form of suicide

Years ago, I would've agreed with Nguyen's philosophy because I didn't want diversity to merely be superficial. But the problem with his notion is that people like him often have very narrow definitions of what is the proper diverse voice. So if a diverse voice was very distinct in its uniquely non-white (or non-mainstream whatever) perspective, he and his type would still attack it if they didn't agree with that perspective.

For example, when Wesley Yang's book The Souls of Yellow Folk came out, Nguyen wrote a very negative review of it in NYT. It's not like I'm a big fan of Yang's or that I even thought his book was good, but negative reviews on NYT are so rare. So why did Nguyen feel the need to attack Yang? It's not because Yang is a fellow Asian American whose supposedly diverse perspective isn't sufficiently distinct enough, but rather, that it's distinct in a way that doesn't align with Nguyen's ideals.

So yeah, in a perfect world, I'd want all diverse perspectives to be distinguishable from those that we deem non-diverse. But I also don't trust Nguyen's call for diversity, and between those choices, I agree with you in that we should side with what allows for more freedom (and, ironically, diversity) of expression.

Wholeheartedly agree. By the way, not to add to your already immense reading list, but have you read any Dave Hickey? I feel like you might appreciate him.