Waiting for the muses

I think it be fair to say that the computer programming has become an obsession, and it’s definitely crowded out most of my reading. But I continue work on the writing. I’m feeling a little unmotivated. Late-stage revision can be hard for me. You can’t change too much, so the process of revising often feels rote. It’s still creative work, but it’s not particularly absorbing–at least for me.

With two books coming out next year, I’ve also begun thinking of my next projects. The process of going from nothing to an idea to a book deal is very complicated. You need lots of freedom and time to think, and you’ve got to pursue ideas without knowing where they’ll go. But at the same time, there is no formal place for it in your schedule. And if you wait until you’ve nothing else to do, then it’s too late–I find that it’s usually at least three years between thinking up an idea and seeing the book come out. Often it’s closer to four or five. So I know what books will come out next year. And my Princeton Press book will likely come out in 2025, but what’ll be coming out in 2026 and 2027? I’ve been kicking around some YA ideas, and if those sold right this minute, they could probably come out in 2026. I’ve done a little work on a sci-fi idea, but that would need to go on submission–realistically that wouldn’t happen until next year. The earliest the book could come out at that point would be 2027, but more likely 2028. So already there’s likely a gap spanning 2026 to 2027 unless I sell another YA novel this year.

Not a huge deal–four years separating my first and second book coming out, and another four years will separate my second from my third. But those years included me developing many projects. I dunno, I don’t have any long-term strategic aims. I just want to keep working. I’ll work in any genre and in any form that maintains my interest. And I like to keep diversified. That’s why I keep writing short fiction, essays, poetry, etc. Those areas are protected from business cycles: you’ll always be able to send out an essay or story or poem, even if there’s a crash.

I suppose at one point a book of mine is likely to achieve more success and push my career in a certain direction, but I won’t know until at least next year if that’s happened / going to happen. For a long time I really wanted to be a serious writer of literary fiction, but I feel less attached to that idea now. Having a career in any one particular field is very much out of your control, and that’s even more true in high cultural fields than in low cultural fields. As a literary critic, work is also the highest of the high. I’m literally opining about, shit, the work of Lady Murasaki or the philosophy of Edmund Husserl. Getting so far up into high culture, I realized, this is a sham. Not that this stuff isn’t better and more deserving of comment–it is. Edmund Husserl clearly ought to be accorded more respect than almost any living writer, regardless of genre, and high culture is the business of creating, preserving and discussing the cultural artifacts that deserve to endure.

But the closer high culture gets to the present day, the more farcical it becomes. Husserl deserves to be remembered, but does Richard Rorty? Peter Singer? Naomi Wolf? Nicholas Talib? Stephen Levitt? When it deals with contemporary works, high culture is indistinguishable from the middlebrow. At that point, it is trafficking not in genuine, lasting merit, but in the appearance of merit. And contemporary works are so cunningly designed that it’s very, very difficult to determine what’s genuinely new and interesting, and what only appears to be so. Moreover, at a distance, high culture performs a sieving function, preserving individual authors not for their own merits, but as an exemplar of the age. For instance, Anthony Trollope is a beautiful and memorable writer, but is he really much superior to Elizabeth Gaskell or George Gissing (other 19th-century proto-Realist novelists). Not particularly. He’s just the person who won out, for whatever reason. When we read and appreciate him, we are reading and appreciating everything about his age that is different from our own.

Whereas when it deals with contemporary products, this same sieving process is distasteful. It is difficult to pretend that a great difference exists between two things, when in reality the only difference is that one of them won out and the other didn’t. And yet, you ultimately have to discuss the winner, simply because everyone’s heard of it, and if you’re truly honest, you know that the loser isn’t so much better that it deserves to have won out instead.

All this is to say, I don’t feel quite so insecure anymore about my ‘seriousness’ as a writer, since I see how much of that seriousness is a manufactured quality. Not that it doesn’t stand in for something real–obviously we should hunger to match the very real merits of the great writers of the past–but, as Basho put it, “Don’t follow in the footsteps of the masters; seek what they sought.” Seriousness, in a contemporary sense, is often merely an imitation of Greatness, and whereas the production of genuine Greatness is a mysterious and unreproducible process–one that often seems to be divinely inspired and outside the control of the individual artist.

Bringing me full circle, I suppose what I am saying is that there is not much room, in an artistic career, for the muses to strike. They won’t appear simply because you need to publish a book in 2027. They’ll appear because they have something that needs to be transmitted. And sometimes you just need to wait.1

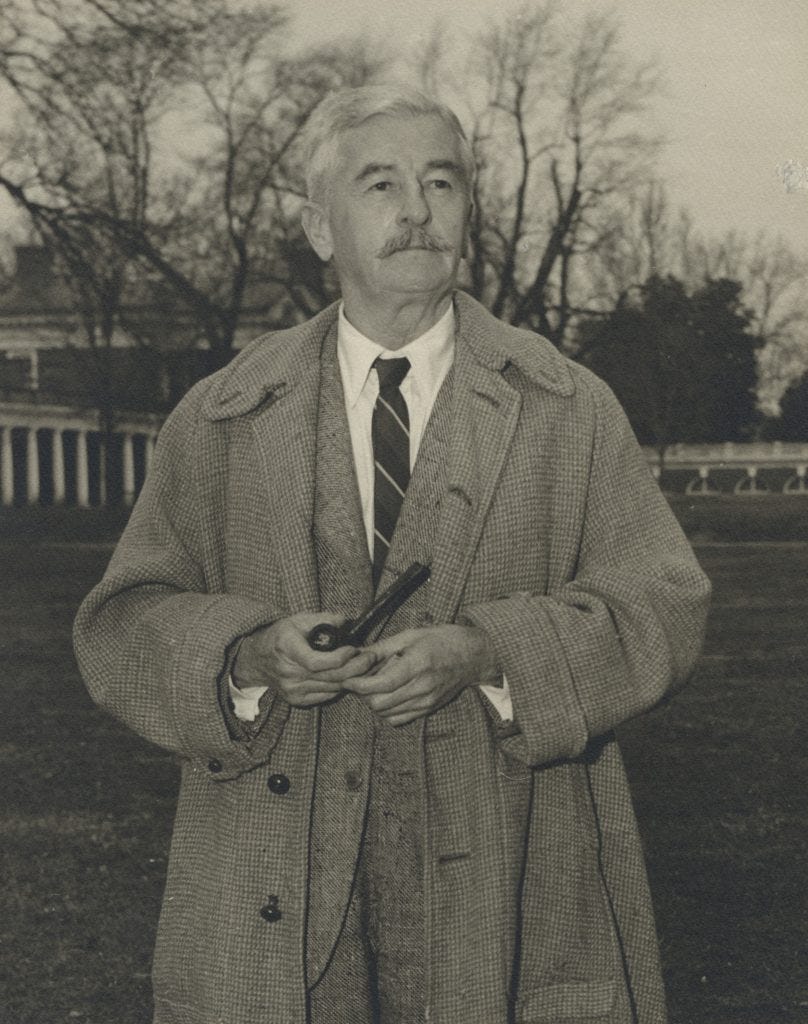

To be more specific, literary authors often have very long pauses between books, but to me this silence is often quite artificial–it’s merely an ersatz form of ‘seriousness’ that makes it appear like they’re working hard and waiting for true inspiration. You’re supposed to respect the seriousness of an author who only writes a book every decade. But most great works of literature didn’t take a decade to write. Virginia Woolf wrote most of her novels in about a year. Tolstoy took only four years to write Anna Karenina. The fact that your book is a product of authentic inspiration shouldn’t be something the critic or reader intuits from the gap between books–it should come from the work itself. Some great works of literature–As I Lay Dying is an example–were written in six weeks. Others, like The Sound and the Fury, took four years. From the reader or critic’s perspective, the difference isn’t really noticeable–all that we know is that both are works of art.