My three difficulties with getting into contemporary poetry

Ever since writing a few weeks ago that I didn't really love lyric poetry, I've gotten back into it in a very natural, organic way. I've been reading it and...feeling feelings? It's really odd. I'm always a little leery of talking about books in terms of emotions and pleasure, because I think, is any book of poems really going to affect me as much as reading Isaac Asimov's Foundation at age twelve? When I read that interstellar retelling of the Roman Empire's fall, I was totally transported, totally present, I was out in Terminus, on the Galactic Edge, waiting in that room for Hari Seldon's ghost to show up and tell us how we've done. I can still remember, across decades, the shock and thrill of the moment when he shows up, and he's just...totally out of sync, not accurate at all (because his theory can't account for the genetic mutant, The Mule, who can control peoples' thoughts.)

Compared to that, what is Wordsworth and Baudelaire?

But the fact is, if I read The Foundation today, or its equivalent, I wouldn't be nearly so transported. And I can't predict when I'll feel strong emotions, as I did recently when I watched Wong Kar Wai's In The Mood For Love. I don't reliably feel strong emotions when watching or reading popular entertainment anymore. I wish that I did! And some of the steady pleasures I seek, like those that come from re-watching old sitcoms or playing video games on my Switch, feel formally empty. They're pleasurable, but meaningless.

I think the twelve year old mind is inherently poetic, it's capable of investing meaning into anything. When I was twelve years old, I had the imagination to make Alyx's death in Phantasy Star IV into an epic tragedy. Nowadays, if I played that game, I'd probably laugh at the overwrought music (I can still hear it) that accompanied her funeral.

If I'd had the time and training and intellect, could I have read Wordsworth at age 12 and felt something? Probably! But that's not what happened.

in reading and viewing high art, one must grapple with the inherently lower intensity of the experience. It simply doesn't feel like art, from the perspective of someone, like me, who was raised on mass culture.

Boredom is my friend, in that high art, while less affecting, is also less dull. The beats are less telegraphed, it is more complex, there's more information in each line and in each moment. Paradoxically, it's precisely the need to pay closer attention, so you're focused entirely upon it, that can make high art seem duller than popular entertainment—high art doesn’t allow us to escape easily from ourselves, because the act of reading it requires us to be so present.

I think that I'm reading poetry just through boredom, because so little else can really captivate me, and so little else seems worthy of my attention. In fact, I've lately been thinking of poetry not as something that reflects the world, but as something that creates a world of its own--poetry is more rewarding than a walk outside, more rewarding than exercise, on a pure experiential level, because it creates a new reality. Poetry works with a gentle touch because it slows down reality and operates at the level of experiential time, as if I'm truly in the time and place it describes.

If the lack of intensity is my first difficulty with poetry, the second difficulty is the evanescence of the experience. Every work exists twice, first in the reading and then in the remembrance, and emotions are the first and grosses information that comes through in remembrance. Since the initial emotions that come from poems aren't necessarily the strongest, the remembrances also tend to be very weak.

What helps is I've been thinking about each poem as, not a collection of images or of lines, but a collection of words. This gives me something that I can hold onto when I think about a poet. Because I can never remember the images or lines, but I can remember more or less what words they use.

For instance, I've been reading Baudelaire, who writes a lot about rot, aging, pain, pleasure, and beauty, and the juxtaposition of the decrepit and the beautiful, as in the following poem:

SPLEEN (III)

I’m like the king of a rainy country, rich

but helpless, decrepit though still a young man

who scorns his fawning tutors, wastes his time

on dogs and other animals, and has no fun;

nothing distracts him, neither hawk nor hound

nor subjects starving at the palace gate.

His favorite fool’s obscenities fall flat

– the royal invalid is not amused –

and ladies in waiting for a princely nod

no longer dress indecently enough

to win a smile from this young skeleton.

The bed of state becomes a stately tomb.

The alchemist who brews him gold has failed

to purge the impure substance from his soul,

and baths of blood, Rome’s legacy recalled

by certain barons in their failing days,

are useless to revive this sickly flesh

through which no blood but brackish Lethe seeps.Anyway, I’m always been haunted by the feeling that poetry is so evanescent. That I read it and then it's gone, and I don't really remember anything, and if I don’t remember it, then how can it really have affected my life?

To some extent this is true of all books! A parent at my kid's preschool asked what I thought of audiobooks, and I said, "Well, when I listen to an audiobook, after about a month I've forgotten everything I heard, whereas when I read a book in print, after a month I've forgotten everything I read."

But with any kind of narrative work or with a work of nonfiction, I can usually remember the main characters, the conflicts, the plot, the themes, major incidents, and a few images. The storyline provides an organizing structure, so I can remember various bits of it like stops along the journey.

I've come lately to think of the book of poems as the organizing unit for poetry, rather than the poem itself. As such I've started to steer clear of the "Selected Poems of" volumes that I used to prefer. Now I go for individual books or for "Complete Poems of" volumes that publish each of the author's books in its original order and in its entirety. The book of poems provides the experience, and I try and remember the bits and pieces that stuck out along the way.

If the first two issues with reading poetry in 2023 are its lightness and its ephemerality compared to other forms, the third issue isn't structural, but cultural. I can google "What is a good TV show" and get a few recommendations and sample them and most will be good. It's very hard to do the same with poetry. There are no readers of modern academic poetry (i.e. poetry by folks with MFAs) that aren't themselves writers or professors of poetry, which means everyone who reviews poetry has an investment in the system. They don’t want to make enemies by giving things bad reviews.

The classics are good--I love Baudelaire--but I've already written about how contemporary work tends to be of higher emotional intensity than classic work (for a contemporary reader), and I found myself craving the immediacy that I get from contemporary work. But when I looked around for recommendations, they were all kind of...the same few names? Ada Limon, Ocean Vuong, Tracy Smith, etc. The winners of the current poetry careerist sweepstakes.

But what if I just don't want to read those ten or fifteen books? Or, worse, don't find them to be particularly good? Very few books of poetry get poor reviews--it doesn't feel like there's any real critical eye there. And, even worse, most books of poems don't have online previews! I can't google them or look them up on Amazon and see what they're like! Even when they do have previews, it's often just a page or two

I started to think I could do better just by walking into a bookstore and looking through the shelves, so that's what I did, going to a nearby store, Medicine for Nightmares, in the Mission District.

At first I was exhausted by all the academic poetry, all written by professors who went to Yaddo and Macdowell, all with the same overwrought lyricism. I texted a friend, "Do you ever find yourself reading a book of poems and think Fuck this shit?" (That was while I was browsing a collection of poems that was all elaborate metaphors for marriage, of the "Marriage is like an axe, it can cut down a mighty tree, but afterwards you've got to clean and oil the blade" variety) (He wrote back "All the time".)

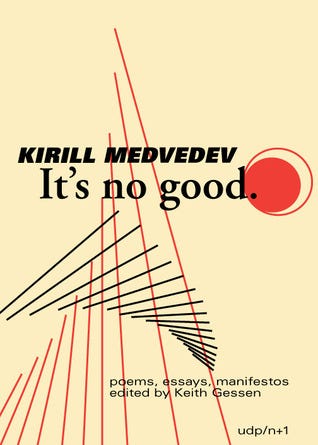

Looking through the rack, I was really drawn to the works in translation, and particularly the Eastern Europeans, and the book I found was It’s No Good by the Russian poet Kirill Medvedev. This book, from N+1 and Ugly Duckling Presse, and translated in part by Keith Gessen, is part manifesto and part poetry collection. The poems are plainspoken, first-person, slice of life, and often deal with the minutiae of being a member of the Moscow intelligentsia in the aughts, but just from running my eyes down the page I could tell it was something different and special.

That's the weird thing about poetry. It's often so immediately apparent that there's no vision there, that the author is just writing an imitation of poetry. And yet every poet has usually spent their life producing this stuff, so it seems absurd that I could know their business better than they do!

I was so diverted by Medvedev's book--it's one of the first times a book of poetry has held my attention as if it was a novel. In the second half of the book, the author loses faith in poetry and the public life of the artist, and he writes searching articles about the role of the intellectual and the failure of the 90s liberal in Russia. They're typical critiques (i.e., that liberalism allows a writer to say and publish anything, but the reader isn't allowed to be changed or transformed by the work. The mere fact that the work is commoditized, bought and sold as an experience, means that the reader opens up the book, digests it, puts it back on the shelf, and then goes back to their life unchanged.) But I think Medvedev comes at these issues from the perspective of someone with a fully-formed aesthetic, who understands truth and beauty, so he doesn't provide easy solutions. He ultimately does want artists to take to the barricades and for their art to inspire people to action, but he recognizes that "art that inspires people to action" is itself a commodity. He writes a lot about the interplay between the art and the artist's biography, and how the biography lends meaning to the work. It's a fragmented and non-systematic approach to the life of the poet (ultimately Medvedev withdraws entirely from the market, renouncing all his copyrights and eschewing the idea of publishing contracts, so he can relate to readers without the intervening apparatus of capitalism).

The manifesto parts can be a little tedious, though I was still diverted, but the poetry itself is good!

Rather frustratingly, there is no preview of this book anywhere online! Most of the reviews quote a few lines, but not entire stanzas or poems (perhaps because of copyright issues). This is a book I never would've bought through online shopping alone.

But in keeping with the author's approach to copyright, I'll include one poem of his that was featured on the Poetry Foundation website:.

On the Day of My Thirty-Seventh Birthday

On the day of my thirty-seventh birthday I ended up involved

in murdering the president.

I was in charge of watching the windows of his palace

and sending back coded reports.

I did everything that was required, and just when I started getting nervous

and things were slowing down like death,

I got a message that said the president had been killed.

Then I split from the crowd of gawkers in front of the palace,

but I noticed that someone else had split off after me,

a man with a strange smile,

that’s all I need, I thought,

I’ll have to take him out.

Leading the man into a little park,

I turned and shot,

and when I ran up to finish him off,

I heard his dying words and the question—

“Why did you do it? I’m a big fan of yours, I love

the Walls song and your ‘Three percent’ book,

I just wanted to ask for your

autograph…”

Shit, I thought, what a missfire.

A tragic missfire, a mistake,

which means the good-for-nothing president

is still alive.I got a number of other books from that same bookstore run, but I haven't read them yet, so let's see if my taste continues to hold up.

My friend Sean Singer has a Substack called The Sharpener you might enjoy. He sends out ~5 poems a day, M-F. I've discovered several new favorite poets this way, and IMO Sean has good taste. Might help with the "how do I make sure I won't hate this book" problem. There's a paid version that includes a craft essay once a week, but the poems are free.

When I read high literature, my experience is something like this: it is like a larger cup to pour from myself into, and that might feel dull at first when the poem is empty, but if I sit with it for an hour it keeps filling and filling, whereas lower entertainment is filled up immediately. And the thing is: when the cup is full, and the cup is large, oh, does it shake me. I invest every word with layers of meaning and memory and emotion and it becomes almost too much to bare.