Maybe the purpose of life isn't to be happy

On Flaubert, Anna Karenina, and May/December

Hello friends. I'm in NYC--just had lunch with my agent, who is one of my favorite human beings. Also met with the team at Feminist Press, who are super stoked about The Default World. I've seen galleys--they look great.

Was reflecting on Flaubert recently, because of this review by Scott Bradfield of a recently-published compendium of the master's letters. I hadn't known that Flaubert was such a recluse, although it makes sense of course. In his brief, turbulent romance with Louise Colet (and the resulting protracted breakup) he strongly resembles Kafka, who was never quite able to commit to Felice Bauer (his letters to her have also been published!) This echoes a theme from Proust, which is that writers don't really need to live, in order to write--we just need to get the flavor of living. With Flaubert especially, it's like he thought, ahh yes, now I have experienced love and longing, and I don't need a stronger taste of them.

I was glad to see this review call attention to an underappreciated aspect of his career, which is Flaubert's broad range. He invented the realist novel, with Bovary and Sentimental Education. But he also invented the hyperrealist novel, prefiguring modernism's union of realist and romantic, with Salammbo, a novel of a very particular moment in Carthaginian history, after the end of the first Punic. It is a sumptuous, Gothic historical novel, well worth reading. His Bouvard and Pecuchet is not as accomplished, but it too is extremely strange: it's about two men who inherit money and they decide to study all possible fields of knowledge, ultimately finding them all disappointing. It's essentially a philosophical novel, in the vein of Candide.

What Bradfield seems to find most compelling in Flaubert is the book's ambivalence about Emma Bovary. Her quest for romantic fulfillment is empty and meaningless--drawn mostly from books and thus incapable of true satiation. On the other hand, nothing else in her world could possibly satisfy a woman like Bovary either!

Bradfield explicitly says that Anna Karenina, to which Bovary is compared, is the inferior of the two books, which is an insane opinion. Anna Karenina is so capacious and loving and humane. But it lacks precisely that quality of reserve that Bovary has. It's one hundred percent clear, by the time you read the end of Tolstoy's novel, what Anna ought to have done in the world of the novel: she ought to have stayed with her husband and devoted herself to raising her child! Tolstoy affirms the marriage bond's sanctity in a way that Flaubert does not.

Both authors felt like modern life was sick and corrupt, but Flaubert's characters usually escape into fantasy, while Tolstoy's escape into traditional life. Of the two, I think Tolstoy's work has proven more thought-provoking, honest, and accurate. Because, given her life, the truth is that Emma Bovary ought to devote herself to hearth and home. She ought to devote herself to raising children and being a wife. That is akin to the point that Mary Wollstonecraft makes in Vindication--middle-class women are raised to find fulfillment only in romance, and since marriage terminates romance, they find themselves with nothing to do, no purpose. It's the 18th and 19th century version of The Feminine Mystique

Both Friedan and Wollstonecraft have similar answers to the question of what do women need. Their answer is, more education, more purpose, and more of a meaningful say in human affairs. In Tolstoy and Flaubert, the answer is more like "less". Less fantasy, less longing, less escape, more acceptance of a woman's role in life, to raise and bear children.

I'm thinking of this apropos of the other Great Books blog I read, Justin Murphy's, which posted recently about how men need to stop looking for women who will share their interests. Personally, I've often found it surprising how you can come across a man who seems like a total buffoon, totally ignorant of manners or of human nature, who becomes fascinating the moment he's talking about, say, history or economics or technology. If you were to judge men without reference to their special interests, they would certainly be judged comprehensively inferior to women.

It is a little funny that Murphy is like, you've got to accept that women aren't interested in intellectual stuff, when statistically the problem is the opposite: women are much more likely to get college and graduate degrees than men, so it's not easy for women to find guys with an education who they can date. I do have friends, both men and women, who complain that a woman's range of interest narrows when she has a child. She can discuss her career and her family, but little else, while men's conversation does not suffer. I haven't particularly found this to be true, but I, personally, do not expect a person I meet in the wild to have the same interests as me. I can count on zero fingers the number of people I've met at a party who are interested in the Great Books.

Lately the thing in Silicon Valley is mimetic desire. It's all Rene Girard. I've never read him, but I guess the idea is we want what other people. We could want anything, so long as others around us want it. That's why everything feels so empty. Rene Girard's like, people turn over rocks, but they find that nothing under the rocks is very interesting, so they go looking for a rock that is so heavy they cannot turn it over. If careers are foreclosed to women, then women want to turn over that rock. If family life starts seeming less attainable, then women want to turn over that rock. We just aim for whatever is difficult.

Seems pretty dark. I don't think the idea of pursuing a goal is that it will provide you with personal satisfaction. Anything worth doing ought to be worth doing in itself. If you raise a child, maybe you didn't enjoy it, but having and raising a kid is good in itself. Same with developing a skill or doing your job well. All good in themselves.

To dismiss human striving as being inherently empty just seem pretty glib. Like...that's the core of life, right there--wanting things, trying to get them.

But capitalism turns human striving into a necessity--you must develop yourself, you must grow, you must improve, you must compete, or you starve or fall behind. There's no sitting still under capitalism, no stability. Because under capitalism there's such a direct reward for striving after career rewards, it does tend to deemphasize activity for your community or your family. That's sort of what both Flaubert and Tolstoy are commenting upon, the way that the ethos of capitalism has infected the middle-class, so there is a relentless urge to perfect one's own life, to experience the best emotions, get the best husband and wife, make the most of your time on Earth. I just feel there has to be some solution that's more than just "stop doing that".

Because, for one thing, it's impossible. We are this way because our society and our way of life conspire to make us thing this way. And, frankly, because it is pleasurable: we experience more excitement, more peaks, more falls, more triumphs, more agonies, than we otherwise would.

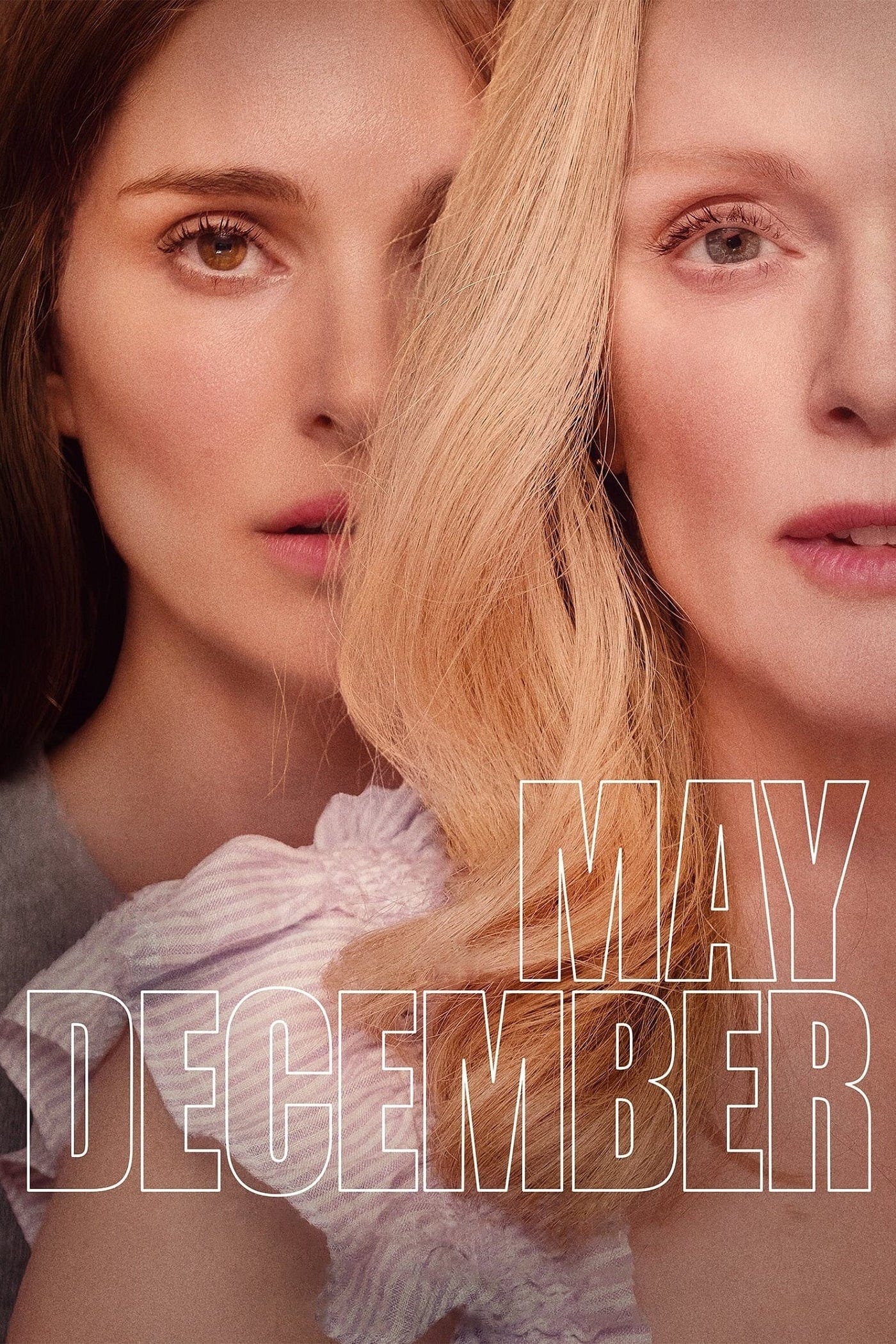

There's some kind of beauty in it--in the way we live. There's something beautiful about how people live in a perpetual state of hope that tomorrow could be different. I watched that movie May December recently, the Natalie Portman vehicle where she plays an actress who's shadowing the sixty year old Julianne Moore and her life with the thirty-six year old man she started sleeping with when he was thirteen (based somewhat on the life of Mary Kay Letourneau, whose story closely resembles that of the woman in the movie, right down to the race of the principle figures). The movie is pretty unequivocal in saying, you know, it was wrong for the Moore character to have slept with this thirteen year old. By getting pregnant by him, she thrust him into manhood far too young, and he's permanently stunted in a way that's apparent in his hunched body language whenever he's around her (Charles Melton might've overplayed the physicality of that last bit, but it was a good performance!).

But trying to read back through time, to imagine the Julianne Moore who did this thing, is a fascinating exercise. And you get the impression she was like Emma Bovary--selfish, yes, but not a predator, per se. She was someone who wanted to relive her own life, to experience a new story, and who somehow got something out of getting to be in charge the second time around. Neither the Julianne Moore character nor the Natalie Portman character are portrayed sympathetically, but they're also not particularly different from you or me. They're fundamentally selfish, fundamentally seekers. The only difference between them is that Portman is selfish within the bounds of the law, while Moore ignores those constraints. It's interesting that Portman sleeps with Charles Melton, in the present day, even though a modicum of thought ought to have told her how hurtful that kind of fling would be for him--he's still the same delicate, gentle person he was at thirteen, and she has the same disregard for his development that Julianne Moore had back then. But now, at thirty-six, it's his job to get over it, in a way that it wasn't his job at thirteen. As Portman puts it the movie's best line, their affair is meaningless: "This is just what grown-ups do". Modern life has the tendency to replace morality with legality--if it's legal to do, then it's okay--with the result, because the law is necessarily expansive and gives people the benefit of the doubt, that there's essentially no penalty for using other people and turning them into casualties of your desire. Julianne Moore lives on this tiny island with her first family--she is forced daily to confront what she's done. While Natalie Portman can jet off and make a movie about it. And yet perhaps that freedom to hurt people (within certain bounds) is okay, and even desirable. Perhaps there is something beautiful and fertile in the controlled violence within our personal lives.

I guess I just haven't outgrown yet my Adam Smith, the notion that "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest." I think, out of all these people, striving for something, we get such diversity, such excitement, such a range of lives.

And if it doesn't make people happy, then so what? If the purpose of life was happiness, we could all just inject heroin.

Oh, I love Emma Bovary because she's so sympathetic in her narcissism--she wants to be adored, and be lusted after, and lust herself, and lead a life of eternal pleasure, which is impossible but also a very natural and easy thing to want. And all the people around her are just as awful in their own silly little desires, which is comforting.

It's been ages since I read Anna Karenina but I remember Kostya's thoughts and doubts being treated as important and eventually reconcilable to goodness, while the spiritual quality of the women characters relies entirely upon their fidelity and nothing else. (The other men are all spiritual washouts, too, in fairness.) At least Emma lives in an equally fallen world. But I could have totally mischaracterized Anna Karenina out of reading it as a feminist student and interpreting too far in one certain way?