It's the most powerful ideology of the last two hundred years, but it will fail eventually.

At some point during the siege, the commander of the defending force realized this wasn't going to turn out well for him. He would fight to the death, because that's what you did in these situations, but still, he did think surrender should've at least been discussed.

And not just for his own sake—maybe his whole country should surrender. Like, yes, generally speaking, when one country is invaded by another one, it usually doesn't go well for the invader. That's because of nationalism, which invaders often find themselves comically unprepared for. They don't understand that even when a country is somewhat ramshackle, people will fight and die to defend it.

But what if this time is different? After all, the army commander's country is not particularly different from the one that's invading it. This country shares a language, culture, and race with that of the invader. So, ultimately, does nationalism even really apply? Why would a small nationalism win out versus a large nationalism?

The problem is that when a country invades another one, yes you might not necessarily want to die for either country, but...do you really want to live in the Empire that would result from their fusion? Some vain, thrusting, overheated mass of nationalism? On the other hand, would it really be any worse than other countries? Is the difference between this place and that place really worth dying over?

This army commander doesn't know. If he was making a bet on his nation surviving, he'd probably still bet in its favor, just because that's what tends to happen. But, you know, something different could also happen. If he was some kid right now, in the suburbs, there is no way on earth he would pick up a gun and go fight. He'd just lie low and wait for it to be over. That's what he hopes his own son will do. Just flee the country and wait for peace to return.

Several years later, the army commander's son gets conscripted into the invader's military, which is working to pacify the remaining rebels.

One day, the fighting intensifies, and the son's unit is encircled. They do not fight to the glorious death, they give up their arms instead.

Because the son is from this place, he is able to pronounce certain words correctly, using the native accent instead of the accent of the invaders. And for this reason the rebels don’t execute him out of hand, the way they do to the other members of the son’s unit. Instead, they offer him a gun, and what can he do? He takes it.

Over time, that's the choice. The invading side is far away, doesn't have its shit figured out. The rebel side is nearby, seems to care a lot. Ideally, you would choose to not fight at all, but nobody allows you to stay quiet. Instead you've got to choose.

Several generations later, a descendant of this man finds herself behind on her rent, facing eviction. She tries to draw strength somehow from her grandpa and great-grandpa, who died fighting for their nation. Fighting for...you know...yeah it was hokey, but for an idea—an idea of freedom and self-determination.

Honestly, though, she was having trouble with the comparison between her struggles and theirs. If she was being honest, she personally felt like capitalism was to blame for her problem. If someone could give her a gun to shoot capitalism, she would. Like...she worked hard. She'd gone to school. She had real skills. Her job was not just some shitty email-job. She had real skills that the world needed. In her job, she helped people. She knew that her work made a difference, and, even more, that her work paid for itself on an economic level.

But capitalism made it possible for some people to get really rich and buy up politicians and then persuade those politicians to shut down certain social programs, and now, as a result, her entire field had ceased to exist.

Her grandpa and great-grandpa had believed in this nation. That it would endure and live on after them. But what did she have to believe in? She couldn't believe in this fucking nation that was built on crushing people like her. She hoped this nation choked. She hoped someone else would invade and put things right. But of course then her own fucking kids would be ground under the boot of some foreign invader. Nationalism was such a virus. And yet, nothing else existed. It was the only -ism left. The only thing to believe in.

Other than, you know, Christianity. She also believed in Christianity to some extent. But even Christianity had paled on her, because she'd walked into so many churches, trying to get help. And it was all the same. They directed you to some social worker or bureaucrat who gave you the run around and told you nothing was available for someone in your situation.

Until, one day...it was different. She walked into a new church, and at this church people actually cared. They didn't have much, but they at least listened to her and offered to ask around and see if anyone had a spare room.

She knew this church couldn't help her, because it was so poor and hapless, it was an immigrant religion, not powerful at all. She, as a native-born person, even poor as she was, felt like she was patronizing them, helping them along.

And later, when she'd achieved wealth and success, she credited everything to this new faith of hers.

This new religion called itself a form of Christianity, but many outsiders considered this faith to be a different religion, not Christianity at all. And...a thousand years from now, people will struggle to articulate why this religion took off and took over from Christianity and Islam. But...it happened.

Decade after decade, this religion expanded. And when the adherents of this religion finally took up arms, they refused to fight each other—instead they focused on invading and conquering the countries of non-believers. One after another, nations converted to this new religion, because, honestly, at least it was an answer of some sort.

And now, three generations later, six generations removed from the original commander, we're in the slightly comical situation where his descendent is encircled and under seige, thinking: I don't think this is going to turn out well for us.

This umpteen-great grand-son thinks: Like my ancestors, both known and unknown, I'm defending a seemingly-hopeless position, on behalf of a nation that seems to be almost extinct. But unlike them, what I'm fighting against is not a rival nation. It's a universal brotherhood, founded in Christ, with the aim of bringing peace to the world. That's a pretty powerful idea. Like, let's be real. That's pretty powerful. And...they're probably not going to make it work. But maybe they will? Who knows! At least it's something!

So the umpteen great-grand-son gathered his men together and said, "Let's surrender."

And because this new religion tended to treat people well when they surrendered, this proposal was greeted with approval. The men surrendered, and their nation, which many great- and great-great grandfathers had fought and died for, was quietly consigned to oblivion.

Of course it never ends, right? Because a thousand years hence, the comments sections of history podcasts will sputter over this moment: "Why did this country finally die just now when, in the past, it'd seemingly beaten back bigger incursions without difficulty? Their nation had endured for so many generations, I'd understand if it'd been defeated on the battlefield, but to just stop believing in it. I don't know. I can't get it. I just don't understand why they didn't fight."

The inspiration for this tale

At some point Trump was doing some saber-rattling about trying to annex Canada, and this story was my attempt to imagine how a war between America and Canada would likely go.

In the modern world, the widespread adoption of coherent national identities has given many states the power to resist incursions by much-larger neighbors. Even when the central government has become weak, the populace still don’t want to be ruled by outsiders, so the people often self-organize into partisans and fight on their own, without being forced to—something that makes them very hard to truly defeat. Nationalism is unquestionably the most powerful ideology of the past two hundred years.

But this state of affairs will not necessarily last. As with all ideologies, nationalism will someday fall apart. What comes next? What new ways will people find for imagining their similarities to and differences from other groups of people? This story attempts to imagine one such possibility for the future.

Although the situation in this story doesn’t really resemble that of the collapse of the Eastern Roman Empire, the joke at the end about podcast nerdery is inspired by my absolute favorite podcast: the History of Byzantium podcast. Most history podcasts tend to focus on narrative: which Emperors fought which wars against which neighbors. And HoB does that, definitely, but it also provides a lot of big-picture analysis of the social, economic, military, and religious life. It’s extremely detailed and well-told.

This podcast, which details the thousand-year history of the Eastern Roman Empire, has finally entered its home stretch. Constantinople has lost all of its Anatolian possessions and most of its territory in mainland Greece. In the episode I’m currently listening to, the city is in the midst of an eight-year siege by Sultan Bayazid I, and Constantinople looks likely to fall any minute (though we know it’ll be be reprieved by the sudden appearance of Tamerlane).

The final loss of Constantinople has been coming for hundreds of years, ever since the Battle of Manzikert. They’ve been fighting and refighting over these scraps for so many centuries!

And whenever this host, Robin Pierson, has a session where he answers listener questions, people say the same thing, “After the incursions by the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates in the 7th and 8th centuries, Byzantium re-oriented its entire social system to slowly fight for and defend Anatolia. They created the theme system, where citizen-soldiers were stationed at key points throughout Anatolia, and over the course of a few hundred years, they eventually won back most of the Anatolian peninsula (i.e. basically the area of the modern country of Turkey). Why didn’t they try and do that again?”

And the answer is that during the 7th and 8th centuries, Byzantium’s comparative advantage was that it had a highly-organized administrative state, capable of levying taxes and maintaining a standing army—something most medieval states were incapable of. And that administrative excellence was really the source of their resilience, because this ability to levy taxes meant that the state had a source of spoils—money to offer to wealthy elites. So instead of breaking away to form their own kingdoms, elites chose to participate in administering this Byzantine state. And administering this state required an education: you couldn’t rise in the service of this state unless you were literate and could function in a way that would allow you to serve in civil or military posts. This education created a cohesive sense of Roman identity that persisted, even during times when large portions of the Empire were occupied by Arab forces and the control exerted by the Emperor was rather weak.

But this whole system degraded over time. First with the Battle of Manzikert in 1077 and then with the sack of Constantinople in 1204, tax revenue dropped. And other states improved in their administrative ability, so Constantinople’s ability to raise taxes was no longer that impressive, compared to financial power of Genoa and Venice.

In the 8th century, Byzantium’s administrative prowess truly stood out: it was by far the most organized state in the region. And that gave it a lot of resilience. But by the end, this wasn’t true anymore because other countries had caught up. Byzantium had no comparative advantages left, nothing to build from—it was simply a nation caught in an unfavorable position, between the Islamic East and Latin West, and it got crushed to dust between opposing pressures from both sides.

As podcast nerds, we are desperate for this state to survive, because we see so much that was good in it. At this point, after years of listening to this podcast, Byzantium has turned into a friend. But ultimately it’s time for Byzantium to go. Their vital energies are clearly lost, spent. They are done.

With regards to America, I don’t have a crystal ball. I’m just spinning tales. After all, in a previous story I compared this moment to the Late Roman Republic. That moment, that period of calamity and disarray, is fifteen hundred years prior to the eventual fall of Byzantium and the final loss of the Roman identity! For us, perhaps it’ll be the same. Who knows! Maybe there’ll be people in fifteen hundred years walking around calling themselves Americans, being ruled by people they call Presidents—hard to say. It’s certainly possible.

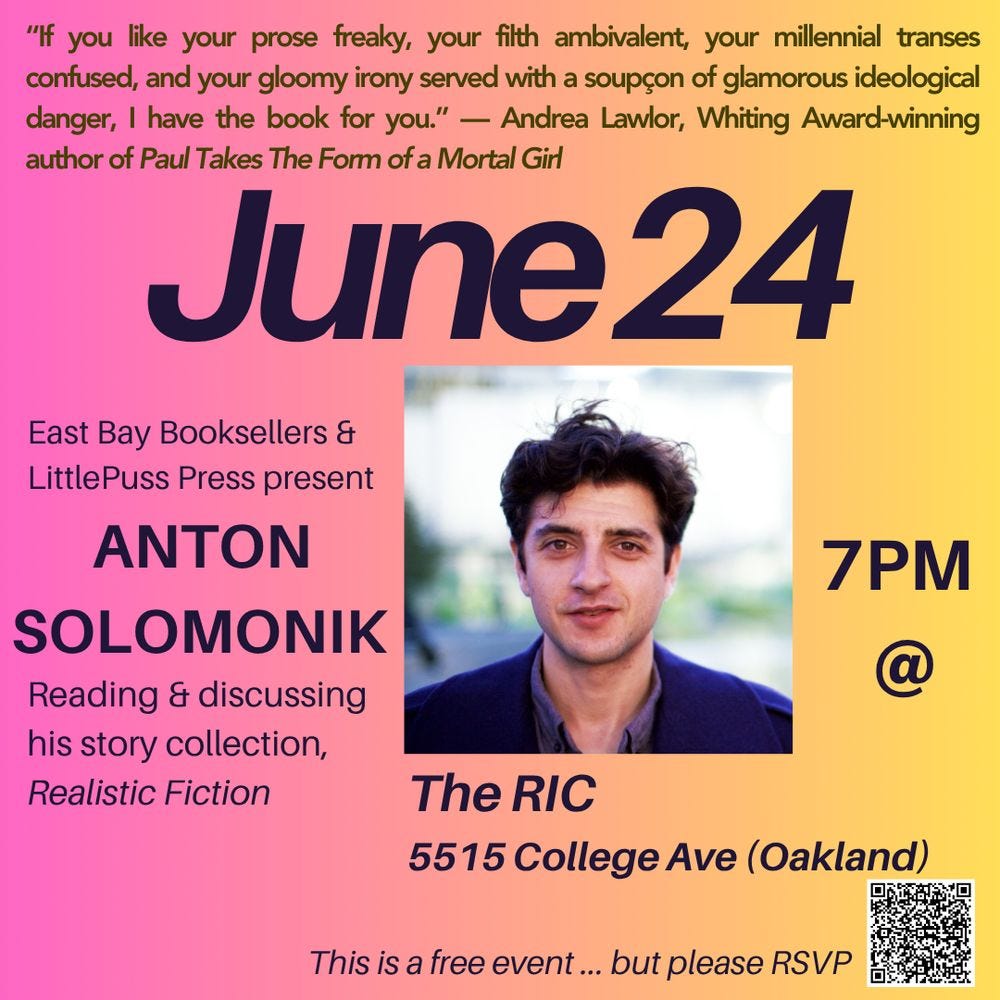

P.S. I am doing an event on Tuesday, June 24th, in Oakland. I will be in conversation with Anton Solomonik regarding the release of his story collection, Realistic Fiction. I heard him read from this book at AWP, and it was hilarious. More generally, I really like Anton and am excited to talk with him next week!

Well, that was thought-provoking, to say the least. Maybe all governments are cyclical in geo-political time. Doesn't help us figure out where America is on that time-line, but it doesn't feel particularly positive. Let's fight anyway, see where that goes. Couldn't hurt. Might even help.

It could well be that Pax Americana us about to begin.