The left owes a huge debt to Nietzsche

Even though he's anti-democratic and anti-equality, he's had arguably more influence on the left than on the right

Before discussing Nietzsche, I want to start with a note on diversity. Implicit in any study of the Great Books is the idea that if a book has stood the test of time, it’s got something to teach us. If I thought that you could open up the New York Times’s review pages and read all those books and get the best that literature has to offer, I wouldn’t bother writing this newsletter.

One thing the Great Books do not offer, however, is much diversity. My wife got mad at me recently because I haven’t been caveating my posts by saying diversity is important and that the Great Books aren’t the only books you should read. I do think that when it comes to Black authors there is a solid corpus of people who you could add to a Great Books list. If I was composing my own list, I’d feel no compunctions about adding Martin Luther King, Jr; Ralph Ellison; and Toni Morrison.

The Black literary tradition probably has the greatest number of authors, out of any ethnic group in America, who’ve achieved canonical status. If you wanted, you could create an education for yourself out of just classic Black authors. Such a list might begin with narratives of enslaved people, particularly Olaudah Equano, Twelve Years A Slave, and Incidents In The Life of a Slave Girl. It would include books by Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, WEB Du Bois, Charles Chesnutt, Mary Prince, James Weldon Johnson, Paul Dunbar, Langston Hughes, Zora Neal Hurston, Jean Toomer, Richard Wright, Ann Petrie, Ralph Ellison, Amiri Baraka, Lorraine Hansberry, Toni Morrison, Charles Mill, Angela Davis, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Bell Hooks, Rita Dove, Gwendolyn Brooks, and others.

But I don’t think there is any other non-white racial or ethnic group in America for which I, personally, would feel comfortable selecting such a list. Like, I love Jhumpa Lahiri. I think the comparisons between her and Chekhov are not unmerited. But do I really feel comfortable saying her aesthetic and cultural importance is on par with, say, Edith Wharton? Not really. I think that requires the level of critical consensus and scrutiny and assessment of cultural importance that, to date, only Black writers have been subjected to by the academic and critical establishment.

Nonetheless, I don’t think only white Americans belong on a Great Books list. Certainly Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, and MLK do. And I hope that in the years to come, there’ll be more discussion about Chicano, Indigenous, and Asian-American authors who can join them. I do believe there are some—I simply cannot confidently state who they are. Moreover, when describing what I, personally, mean by the Great Books, I thought it was important to be honest. When I think of the Great Books I don’t think of some platonic ideal of a system that Cornel West and Henry Louis Gates and Sam Delany and Jhumpa could come up with if they got together. I wish that system existed, but it doesn’t. What I think of is a real, concrete list that comes in a book that’s on my shelf—a book published in 1999 by a 90+ year old Columbia professor. The left likes to talk about how ideas are socially constructed, well, this is what that means. When dealing with an idea, you must deal with the part that has real, concrete, actually existing reality: you must deal with the idea as it lives and functions in the world.

Anyway, this is a natural segue for discussing the man who popularized the idea that morals and values are socially constructed: Friedrich Nietzsche

Am more or less done reading Nietzsche. My favorite work of his was The Antichrist, which summarizes his critiques of the Christian religion and elaborates upon how he thinks society ought to operate. Nietzsche is a logical and consistent writer. From Beyond Good and Evil through to Ecce Homo the only major theme that dropped out was the idea of the Ubermensch (the over-man, as Kauffman translated it), and I think the over-man was largely a poetic device (it primarily appears in his novel Thus Spake Zarathustra).

Nietzsche was relatively straightforward in his beliefs: he believed inequality was good. Most people were meant only for mediocrity; their souls crave mediocrity. He describes it all here in The Anti-Christ:

Handicraft, trade, agriculture, science, the greatest part of art, the whole quintessence of professional activity, to sum it up, is compatible only with a mediocre amount of ability and ambition; that sort of thing would be out of place among exceptions; the instinct here required would contradict both aristocratism and anarchism. To be a public utility, a wheel, a function, for that one must be destined by nature: it is not society, it is the only kind of happiness of which the great majority are capable that makes intelligent machines of them. For the mediocre, to be mediocre is their happiness; mastery of one thing, specialization—a natural instinct.

And what if someone with superior abilities got mistakenly consigned to a lower caste? Well, they would suffer, but I’m not sure that Nietzsche would consider that a flaw. He didn't regard suffering as a problem, or as something to be overcome. The struggle for freedom was, to him, more meaningful than actually possessing freedom. If a great man was assigned to the wrong caste, then that would give them an opportunity for struggle, and it would make their life meaningful.

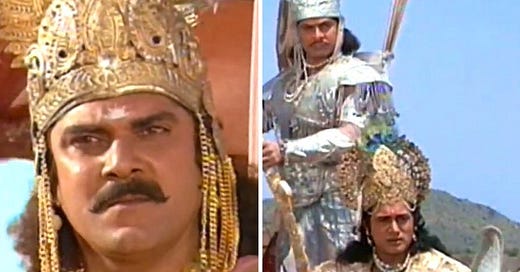

Nietzsche was quite influenced by Hinduism, and the classic Hindu story of a man accidentally assigned to the wrong caste is Karna. He's actually the sun of the Son, and the eldest of the Pandava cousins, which means by rights he should rule instead of Yudhisthira (the King whose stolen birthright is the main driver of conflict in the story). But Karna’s mother is afraid because she conceives him before she’s married, so when he's born he's set afloat in a basket, and he's raised by a chariot-driver (i.e. lower-caste person).

Karna grows up feeling instinctively that his destiny is to be a powerful warrior, but he's held back by his low caste. He has to trick teachers into instructing him in the warrior arts, and when they find out the truth, they lay upon him the curses that will lead to his death. When he first meets the Pandavas, at an archery tournament, they mock him, and Arjuna (the most powerful warrior amongst the Pandava cousins) refuses to compete against him.

In response, Duryodhana, the main antagonist of the epic, embraces Karna, calls him a brother, and makes him a King, which entitles him to compete. Karna eventually realizes the truth, but he refuses to change sides, saying he’s eaten Duryodhana’s salt and is committed to defend him. Karna eventually takes over the generalship of Duryodhana's armies during the battle of Kurukshetra, and he's only defeated when all of the various curses levied against him come into effect at once.

None of this undermines the Hindu notion of the caste system. Karna’s upbringing pollutes him, and as a result he is not fated to rule, but his inherent character shows through, and his tragic end is laudable--an ideal. Everyone in the Mahabharata acts according to their dharma, even Duryodhana and the wicked uncle Shakuni. They all have some certain fate that they enact, according to a grand scheme that is beyond human comprehension. As Nietzsche himself says, in a noble society, someone might be your enemy, but that doesn’t make them bad: the only bad people are the lower castes. Karna suffers, but he remains great.

If human suffering isn't something to be avoided, then it's hard for a modern mind to levy any charges against any particular social system, really. And if the purpose of a social system is to maximize greatness, then inequality, unfairness, and conflict might be more productive of greatness than their opposites.

I've tried at times to write a fictional retelling of Karna’s story, but I've always abandoned it, because everything about the tale is already exactly what it needs to be. It's written for maximum effectiveness, maximum conflict, maximum ambiguity. The conflicts it generates ultimately become their own justification. That's the essence, I think, of greatness (or, to use a different term, of what Edmund Burke called "the sublime"). You want to hate something, want to tear it down, change it, make it more palatable, but you can't, because it is beyond human morals and human ideas of justice and fairness.

In terms of his influence on the world, Nietzsche’s too anti-religious and too much in favor of individual freedom to really resonate with the modern right. The modern right doesn't want to remake all values. They know the values they want. Christian values.

Whereas Nietzsche strongly intended for his method to be constructive. He wanted to free mankind to discover new and better goals--ones centered in real, concrete existence, rather than some abstract utopia, either in heaven or on Earth. As he wrote:

There are a thousand paths that have never yet been trodden—a thousand healths and hidden isles of life. Even now, man and man’s earth are unexhausted and undiscovered.

At first it was the French existentialists who heard his call, but their commitment to equality degraded the quality of their message. When everyone is responsible for finding their own health, their own hidden isle of life, the result is only noise. Nietzsche proposed something different: a few brilliant and courageous minds needed to find new modes of being, and then they should construct societies that shepherded the masses along those paths.

What the left ultimately took from Nietzsche wasn't the notion of hierarchy or the idea that human suffering was to be embraced. Instead they took the notion that morality is culturally constructed, and that it's often constructed for the benefit of the ruling class. With that idea, most evident in Foucault, all morality became contingent. But they lacked Nietzsche's aesthetic sense: his ability to sort through systems of morality and divide them according to which was beautiful and which was ugly.

Meanwhile, Nietzsche's genealogical method--mapping the secret power dynamics that lay behind systems of morality--proved intensely destructive in the hands of literary theorists, so the end result was noise, a sense that everything was contingent and nothing meant anything, and that the only path to freedom was for society to totally change (but then even that complete change would itself be meaningless and contingent...)

Anyway, Nietzsche's not exactly something to construct your life around, but he's more rewarding than Schopenhauer or Hegel (though not more so than Kant), and certainly one of the most beautiful and stylish writers in any language. I've tried to get into him a few times, and I think if you were going to read one book, The Antichrist would give you what you needed. But if you were to read three books, I'd say Genealogy of Morals, Thus Spake Zarathustra, and The Antichrist (in that order).

Further Reading:

Jurgen Habermas is probably the most-respected philosopher alive today, and he’s written an excellent book Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, which traces the development of Continental Philosophy since Kant, and the various attempts to use pure reason to arrive at moral values. Best $37 I ever spent =]

I think every single Indian-American millennial remembers watching this serial with their parents: BR Chopra’s Mahabharata. As I recall, we usually rented it one VHS tape at a time from the Indian store. God knows where they got the tapes from: they were clearly copies of copies.

Great Books Elsewhere On The Web

Ted Gioia is a perfect example of the kind of freelance intellectual who’s heavily influenced by the Great Books. Both he and his brother, Dana, are champions for culture in its truest sense. One of the posts I most enjoyed this year was Ted’s Lifetime Reading Plan. The way he describes reading is how I used to read when I began my journey, right after college, and was trying to read the Great Books while writing my own stuff and working a full-time job. His reasons weren’t the same as mine (I wanted to become a great artist, not improve myself), but they still resonate:

I wanted to develop a meaningful philosophy of life. That seemed urgently important to me as a teenager. It still does today. I wanted to take the high road, with the right values, and pursue the best goals. I wanted to appreciate the world around me more deeply, more richly—and not just the world today, but also the world in different times and places, as seen by the best and the brightest.

Some people will tell you that this is elitist. But I have the exact opposite opinion. For a working class kid like me, this was my way of overcoming elitism. Some elites even tried to steer me away from this project—as not appropriate for somebody from my neighborhood and background.

Take a publishing seminar with me!

Oh, finally, my last side hustle was that I wrote a guide to getting your book published. I teach a little seminar based on this book where I try to help people come up with hooks for their own books. I’m very gentle and affirming: I really enjoy talking to people about their book ideas! The class is August 8th, 4:30-6:30 Pacific Time. It’s through StoryStudio. Enrollment is closing soon so sign up today if you want in!

The problem right now is that the left craves a moral system, but neither the Nietzschenian dissolution of all values or Marxism (the other dominant left tendency of the last 100 years) can provide that. Which is why so much of left morality is liberal bourgeois manners with radical slogans. Practically, this is open to abuses (call out culture, basically), and, intellectually, this is thin gruel compared to the before mentioned ideologies (as well as conservative Christianity and classical liberalism). But I don't what the path to a left moral system is. We struggle to build on the strange intellectual heritage that Nietzsche has provided us with.

Good writing as always though!

I remember two sayings from my reading of Nietzsche, which sum up much of my academic experience, in fact.

1. “The will to a system is a lack of integrity.” I destroyed a graduate student in Philosophy critiquing this sentence, by pointing out the Nietzsche was not making a distinction between good and bad systems-he was saying that any system, externally imposed or internally selected, was a crutch that reduced one’s freedom. I thought this idea was rather exciting, in the way many 19 year olds might. It seemed that none of the other students had any idea what we were talking about, but later I realized they were just more prudent than me.

Later in the same book, I read another line which ended my fascination with Nietzsche. If you are familiar, perhaps you can guess the sentence?

2. “When going to women, carry a whip.” Perhaps this is a slight paraphrase, but you get the gist here. Having grown up on a ranch where whips were used for a variety of purposes, none of which involved men wanting to date me, it was immediately apparent that Nietzsche’s idea of what constituted “mankind” was extremely narrow, did not include me (one of those ‘women’ he felt such a need to both approach and protect himself from), and showed that that other interesting thing he said to be a miserable lie. I still got an A in the Intro Phil course thru the simple expedient of not bothering to try to discuss this with the graduate student at all. I expect the other students were grateful for my forbearance.

I had already encountered the same problem with Freud, when I realized that anytime he spoke of sexuality, he was discussing male sexuality, with “the female” being the focus is sexuality, not an active generator of sexuality for myself, and a rapid scan forward from tat point convinced me that Freud was a puzzled man too limited by the cultural milieu within which he found himself to address how women actually interacted with men at all. But Nietzsche was the last straw. I turned to neuroscience and the oversimplifications of Skinnerian behaviorism after that. Ugh.