How to start your para-intellectual career

On placing long essays with little magazines (in the hope they go mini-viral and get you a book deal)

Shortly before I got into a shouting match with the editor-in-chief of the The Los Angeles Review of Books over this essay, she asked, “Is this supposed to be literary criticism or a book review?” I said, “Err, both?” And she said, “See, that’s the problem, those are two completely different things!”

I have mulled over this for a long time. Some books reviews are just a chronicling of the good and bad within a book and a recommendation on whether or not to read it. But many book reviews aim much more broadly than this. The critic takes the review as a jumping-off point for some larger point. An example would be George Orwell using the occasion of the republication of some of Kipling’s poetry to discuss the poet and novelist’s place within English literature as a whole:

It was a pity that Mr. Eliot should be so much on the defensive in the long essay with which he prefaces this selection of Kipling's poetry, but it was not to be avoided, because before one can even speak about Kipling one has to clear away a legend that has been created by two sets of people who have not read his works. Kipling is in the peculiar position of having been a byword for fifty years. During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him, and at the end of that time nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there.

This latter sort of review usually only comes when the reviewer is assigned a nonfiction book or a career retrospective of some kind, but, as N+1 memorably called out, most critics dream of writing these essay-type reviews, and there is a tendency for critics to turn ordinary book reviews into essay-reviews.

What makes a Contemporary Themed Review, or CTR for short, is its emphasis on terms. The CTR addresses books in groups, and by theme: the internet novel, the sanctimony novel, the millennial novel, the #MeToo novel, the climate change novel, the autobiographical novel, the permalance novel. The term is always singular, suggesting both gravity and homogeneity. In foregrounding theme, the CTR begins at its end, announcing its concerns in the opening paragraphs or even in the title, like an undergraduate essay. The journey, the destination, and the origin are one and the same. Any number of books can be combined in a CTR: as with the salesman in the blender commercials, the answer to the question “Will it blend?” is always predetermined.

The problem is, who wants to write a regular old book review? You’re not getting paid much for a review. What you want is not to write a work-a-day piece but to write something that’ll arouse comment, something that’ll be quoted, retweeted, and shared. And to do this, there needs to be a crisis, and you need to tie your book review into the political moment somehow! This book review must be about something bigger than books!

I still have absolutely no clue what the difference is between literary criticism and a book review. I know lots of literary criticism isn’t book reviews, and lots of book reviews aren’t literary criticism, but I also know some things are both? Then N+1 also introduces this third thing, cultural criticism, but doesn’t define it: “But the CTR departs from this tradition of cultural criticism, which was produced by writers who like good Marxists saw the entire point of criticism as drawing connections between literary form and socioeconomic form, and who like good anti-Stalinists took pride in doing so in ways that weren’t completely obvious.”

I think much of this is explained in a recent John Guillory book I haven’t read, called Professing Criticism, about the way literary criticism and teaching English literature at a college level came to be seen as synonymous.

This is a book I’ll read someday, but for the purposes of this essay I don’t think I need to, because this essay is neither literary criticism, nor a book review, nor cultural criticism—it’s merely a how-to blog post.

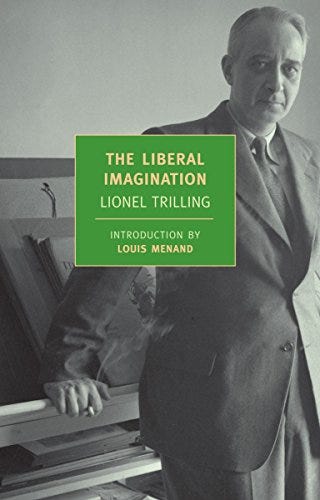

Everyone wants to be this fella

Ever since I cracked open my first collection of Samuel Delany essays at age 20, I’ve wanted to write erudite literary essays, full of references to old literature and discussions of obscure authors and mentions of literary feuds and scandals and plagiarisms.

I’ve recently discovered that this is not an uncommon ambition. It’s astonishing the number of people who want to write, not fiction of their own, but essays about fiction. As a friend who’s a professor of English told me, after I explained my book to her, “My students would love you. They keep asking me how to get published online. They want to do the kind of writing that doesn’t have footnotes.”

There are, I assume, two paths to doing this kind of writing.

NB: This is where the paywall begins. I am sending this message to all subscribers, but if my free subscribers are really annoyed at getting a paywalled post, please email me at rhkanakia@gmail.com, so I’ll know to stop doing it.