Creating beauty is a more practical goal than "helping people"

Ugliness and evil are far from synonymous. Some people are evil but not ugly, and some people are ugly but not evil. When it comes to our sense of a person's aesthetic value, their physical beauty almost always predominates. It is very possible for an evil person to be beautiful, and when that occurs, we cannot really say that the person, as a whole, is ugly.

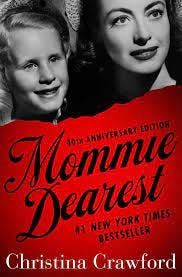

Take, for instance, Joan Crawford. I have no trouble saying that she was evil. She adopted five children and abused them. What a psycho! But looking at her face, you immediately think, "Oh she was in such pain! Oh but her evil was so operatic, so larger-than-life, so noble, in some way."

Beauty ennobles. I'm not saying that's right or good. I'm just saying it is a fact. This is the difficulty intellectuals have with fascism and communism. In its iconography, use of music and images, fascism is often quite beautiful (except in its oddly-very-ugly American manifestation, where even the thin blonde fascists often have a rather brittle, skeletal quality, a la Ann Coulter or Kellyanne Conway). Similarly, communism is, most often, rather ugly. This is not universally the case: Che Guevara and Fidel Castro were physically handsome, and very dashing in their various garbs. And some of the Social Realist aesthetic--particularly when focused on industrial production a la the Gladkov novel Cement--had a beauty to it (rather ironically, the most beautiful part of Ayn Rand's works, which are staunchly anticommunist, was precisely this celebration of industrial production that she must've hijacked, on some level, from the Soviets). But generally, communism is rather ugly, with its petty disagreements, internal schisms, and constant bureacratism. And yet communism is much better--more good--than fascism, because at least communism aims for the good for all people.

But leaving aside the clash of the physical and the moral, there are also personality elements that are both evil and beautiful. Selfishness, for instance. It is the epitome of evil, but it is essential for true beauty. We cannot value someone who doesn't value themselves--that is basic psychology. Authors have exploited this tic to grotesque advantage. On Substack recently someone mentioned the novel Angel, by Elizabeth Taylor, about a popular novelist who is monstrously self-absorbed, to the point where she doesn't even understand goodness. She's very much in the vein of Becky Sharp and Scarlett O'Hara, two evil women who are impossibly compelling on the page.

Nietzsche drew a distinction here between goodness and nobility. Goodness, a Christian virtue, consisted in doing good for others, serving others. Nobility was high-mindedness, it was the ideal, the heroic, the beautiful. But is Scarlett O'Hara really noble? She is horrifically stupid. Her impossible dimness can only spur contempt--and her drive to grasp and possess whatever others desire seems the epitome of baseness. She wants Ashley Wilkes, despite her contempt for his essential nature, only because Melanie wants him. That's not exactly something you'd see from Odysseus or Achilles.

It's simply impossible to conceive of pure selfishness as being good, because it is so empty. It contains no aim or end, other than the expansion of our own powers. I've been reading about the First Emperor--the man who united China--and he seems, and has been regarded as, rather evil. He created and profited from a mechanized society, built around war, and seemed to see no higher purpose than to unite the universe under his rule. He had no broader vision, no sense of mankind's possibilities. He was evil, and yet...beautiful.

To the moralist, the juxtaposition of evil and beauty is difficult--they're tempted to explain it away. They want to slice off evil and separate it from beauty, saying that he was good in his pursuit of order, but bad in his cruelty. But to the novelist, the compatibility of beauty and evil is very fruitful. One is tempted to say that writing stories would be impossible if there wasn't some beauty in evil, precisely because beauty compels the eye and ear and attention, while evil repels it.

The interesting thing is that we are repelled by evil, but aren't necessarily attracted by good. That's because good, like selfishness, can also seem rather empty. Where selfishness aggrandizes the emptiness inside; goodness aggrandizes the emptiness outside. Nobody has ever written a novel about Mother Teresa, because it would be no fun--she raised money to help people, so what? Indeed, if we did write the novel, it would almost need to focus on her darkness: her hospitals weren't very good at providing medical care, and she gave unwanted deathbed baptisms to her Hindu patients. She prioritized their spiritual well-being over their physical well-being, and SHE was the one who defined what spiritual well-being entailed.

Ugliness, on the other hand, is a nullity in the text. It, like goodness, is merely boring. The ugliest character in literature is, to me, Dickens's Uriah Heep: the creepy, oily ingratiating fellow-clerk of the protagonist from David Copperfield. Uriah is always on the make, always out for himself, but in a way that feels very vacuous, very hard to pin down. He can only fit into a novel because this particular book is large and capacious and Uriah is only one element in a very complex mixture. The main juxtaposition late in the book is between Uriah Heep and Mr. Micawber. Micawber--based on Dickens's own father--is a constant debtor, who can't seem to keep from spending money, and whose penuriousness keeps his family in constant poverty. But Micawber behaves with nobility, sacrificing his position in order to thwart Uriah--and yet, isn't that lack of care for himself exactly what leads his family to poverty?

The task of the novelist is to judiciously use beauty to manage the reader's interest in what is, usually, a morality tale. Sometimes beauty seems to be on the side of good and sometimes on the side of evil. The difficulty, however, comes from including what is, to my mind, the largest part of existence: ugliness.

How do we find a place for ugliness in our books? It's not really an easy task. Ugliness is an instant bore. You need to be a master, like Dickens, to allow even a tiny dose of ugliness in your book. Most authors can't manage even that. Usually writers alternate between showing the allure of evil and the allure of goodness and the allure of beauty for its own sake (i.e. nobility), but they can't ever manage to show ugliness, because ugliness has no allure. Ugliness is what happens when we don't think, don't try, don't expend effort. I've given up trying to incorporate ugliness in any systematic way--it's simply beyond my efforts. Some authors attempt to write about ugliness, but they only make the ugly seem beautiful (i.e. Charles Baudelaire, with his evocation of rot and death and filth). But the nature of ugliness lies precisely in our experience of it as ugliness. If we experience it as beauty then although the writer might have created a very skilled performance, they still haven't shown the essential nature of the thing.

What's attractive about beauty is its concreteness. Abstractions can be beautiful, but beauty tends to the individual, the particular. Since novels need to be filled with a determinate content, with specific people, situations, traits, actions, words, characters, it's only beauty that can allow us to choose what to leave in and what to take out.

When the concrete and universal are tied together, we get the ideal. It's a human being who is particular, who arose in a particular time and place and does some particular actions, but is inhabited somehow by an abstraction. Mother Teresa is a perfect example: she was an Albanian nun, but also the personification of charity. And in exploring the individual, we also explore the contours of the ideal, as we do in evaluating the troubling (could we even say...ugly?) side of Mother Teresa's works.

I do think beauty has a place in moral education. Beauty can direct us towards what is good, but do we really need beauty for that purpose? Good is rather simple. Good is self-sacrifice. Good is helping others.

Good is boring because it is so simple. It is beauty that is infinitely complex, and I think learning to avoid ugliness is a good in itself. If I believed there was a moral imperative to avoid physical ugliness, I would be an aesthete, which I am not. But I think in many cases avoiding ugliness can be a more fruitful source of guidance than can the imperative to avoid evil. Most of our life doesn't have the strongest moral implications. The beauty of capitalism is that it turns most of our social relations into economic ones. We don't need to be good lords or good tenants or good clients or good servants--we simply need to be good enough to get paid. Indeed, it's debateable whether it's good at all to provide service in excess of what we're paid for. There's no per se need to care for anyone outside your own family, and if you do care for other people, you can discharge that care by donating money to them (under capitalism, perhaps all goodness is merely Sam Bankman-Fried's Effective Altruism). Indeed under liberal capitalism, perhaps the only respectful way of caring for another person is to give them the money to purchase what they believe to be their most pressing need.

Nonetheless, you can still act nobly. You can invite your neighbors over to dinner simply because that is more beautiful than expending your excess energies watching television. You can take care with your words and with your duties simply because that is the beautiful thing to do. You can labor over your personal appearance and your meals, simply because that creates more beauty and pleasure in your life. Beauty also guides us as to which of our pleasures are more fruitful than others. Beauty teaches us a more responsible hedonism. Yes, getting stoned all the time is fun, but it's also ugly. Yes, binge-watching TV or scrolling Twitter is fun, but it's ugly in the extreme to imagine that we are simply doing exactly the same thing as everyone else on our block, in all their individual houses--beauty creates the imperative to develop ourselves in our particularity, and our aesthetic sense also guides us to the nature of that particularity. What in our own life, would be more beautiful? What action, what decoration, what activity?

Like, at some point all my friends wanted to "help people" with their jobs, so they got soul-sucking poorly paid nonprofit jobs. Then they wanted to be comfortable, so they got tedious overpaid tech jobs at companies engaged in creating the most silly, banal, trivial, useless services you can imagine, and now they worry their lives are meaningless. But perhaps if from the beginning they'd looked for grace and beauty, they might've had more guidance as to what, in its specificity, would've been a worthwhile thing for them to bring into the world.

Naomi, I’m a pretty new subscriber, and I want to give a general compliment to your work. You help cut through the bs of modern discourse and do it with style!

On ugliness in literature - I must recommend “Perfume: Story of a Murderer” by Patrick Suskind. Grenouille (the main character) is the absolute peak of human ugliness, which the author extremely skillfully balances out with one element of beauty: scents. The pursuit of beautiful smell gives the character nobility even as he himself (and the majority of odors) are utterly repulsive. I’ve never read anything like it and I think it does pull off some great depictions of ugliness because it is using one sense (that is not often used in literature) to such an extent.

Interesting Naomi. Not sure I'm with you that Nazi propaganda was more beautiful than the Soviet one, what I've seen is quite vulgar, mean and simply dumb, whereas some Soviet art was quite creative and at times beautiful - but sure, my survey wasn't extensive. There is something fascinating about near-pure evil, a sort of detachment that is not there in petty evil, but I would distinguish that from beautiful.

Your point about beauty as a useful guide to decision did stir me. Not sure I'm fully with you, but certainly is true that at times, one cannot help being sad or dark about things, and some of such times, beauty, either from outside self or self-lived, can give solace. It can give the inspiration to pull oneself out of a hole of darkness and back to joy - which I think has its own kind of beauty, the type I prefer of course.