Being a mass murderer may not be a particularly great job

On Zone of Interest

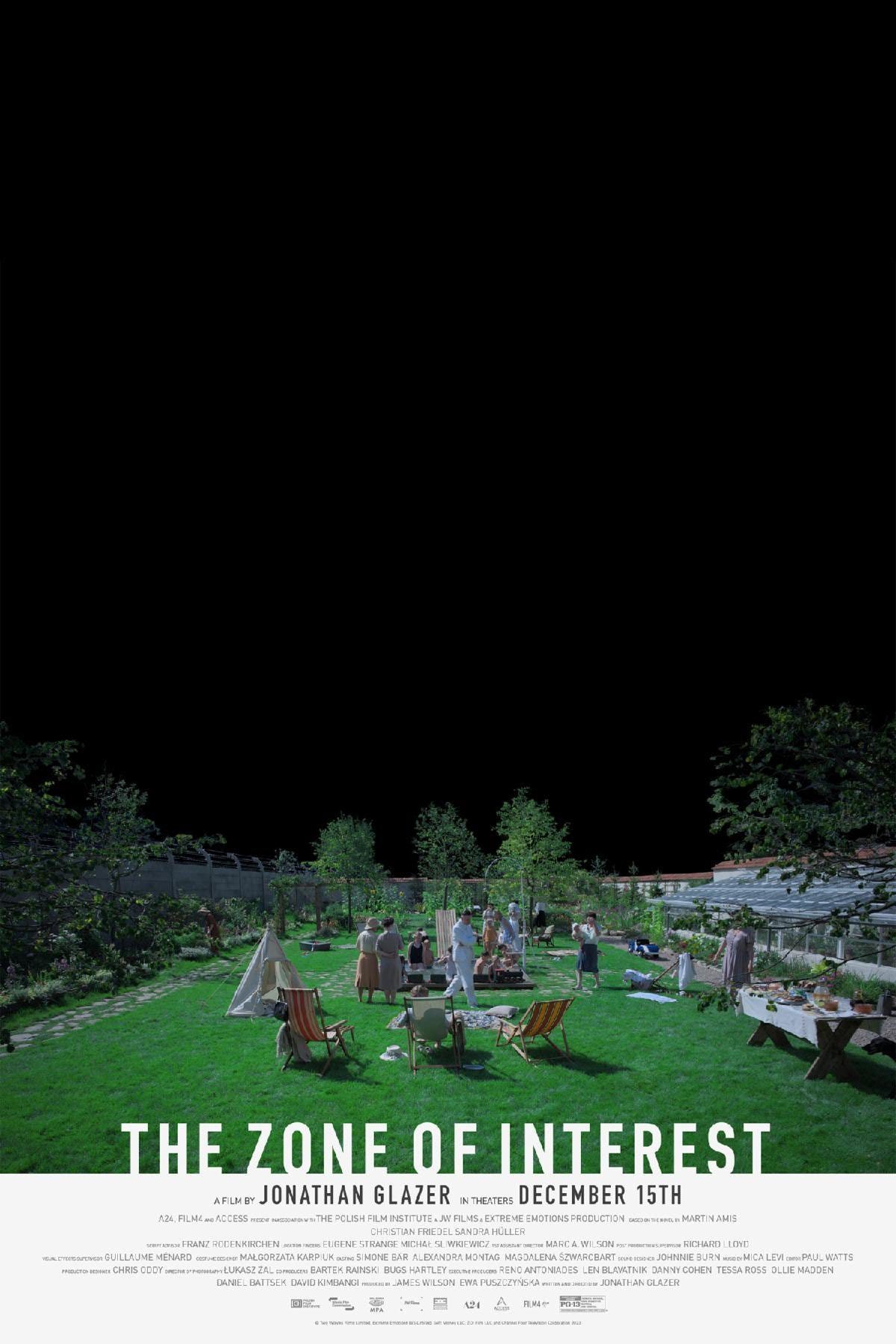

I watched Zone of Interest recently. It's that German flick about Rudolf and Hedwig Hoss, and their ordinary domestic troubles as Rudi goes about his day job of running the Auschwitz concentration camp.

The first half hour shows an idyllic life, mostly from the point of view of Hedwig, who is portrayed by the same actress who played the main character in that French movie Anatomy of a Fall (Sandra Huller had a really good year!) And I was like, oh okay, I get it, this is one of those banality of evil movies. The Nazis were just like us!

The Hoesses have a beautiful house, next to a river, surrounded by verdant fields, with a lovely garden and pool and lots of domestic help. The kids are tow-headed and adorable. Rudi and Hedwig seem to be as much in love as a couple with four kids can be. When Rudi is faced with a transfer to Orianenburg, his wife rebels and says "We did exactly what Hitler wanted. We went East and found living space! This is our living space!" And it's genuinely kinda sad: you're like what's gonna happen to these two crazy kids! Sure hope they can work it out.

The genocide is shown only in glimpses, mostly as belching smokestacks and the tooting of trains and the barking of dogs and the distant firing of bullets.

I'm on record as saying that I'm a bit bored of the banality of evil. Not that it isn't a true or useful concept: I just think it gets people off the hook a bit too much. We are very fond nowadays of the word "systemic". We keep positing a crime without criminals.

But human society is nothing more than the individual actions of human beings. Yes, you or I, if we found ourselves married to Rudolf Hoess, would probably also wear the fur coats of death-camp victims. It is true, we would succumb, we would do the bad thing, we are no better than the Hoesses. But...isn't there more to life than moral comparison? Let's leave aside the question of blame. Surely we can agree that something rather unusual happened at Auschwitz! Something that all of Western society is still reckoning with! It was definitely not a banal occurrence.

I think for me the way out of the banality of evil trap came with a novel I read last year: Imre Kertesz's Fatelessness. The book is told in an ingenuous faux-naive tone: it's about the travails of a fourteen year old Hungarian Jewish boy who is is sent to Auschwitz and survives through a series of strange coincidences.

The persistent theme in Kertesz's work is that life in Auschwitz was just life. A step taken at Auschwitz is no different from a step taken at home. A conversation at Auschwitz is just like a conversation at home. There is no magic barrier, marked Auschwitz, that walls the camp off from ordinary life. What this means to Kertesz is not that Auschwitz was banal or ordinary, but that real is an Auschwitz: we are all living in an Auschwitz, all the time. Everything that happened there is something that happened right now, in the real world in which we live.

“Why, my dear boy,” he exclaimed, though now, so it seemed to me, on the verge of losing his patience, “do you keep on saying ‘naturally,’ and always about things that are not at all natural?” I told him that in a concentration camp they were natural.

Or, later:

“In any case,” I added, “I didn’t notice any atrocities,” at which, I could see, they were greatly astounded. What were they supposed to understand by that, they wished to know, by “I didn’t notice”? To that, however, I asked them in turn what they had done during those “hard times.” “Errm, . . . we lived,” one of them deliberated. “We tried to survive,” the other added. Precisely!

The way it's used nowadays, the function of the banality of evil is to wall off evil from ordinary life. It is to say, sometimes men do evil, and then they come home and pet their dogs and hug their wives. The evil is separate from the rest of them.

But, fortunately, Zone of Interest isn't a banality of evil movie! It's so good, so breathtaking, so ambitious, so human and well-structured. I don't have the works for how well-made the film is. Because things start to fall apart for the Hoesses. And it's not like their evil catches up to them--far from it. But life turns into a grind. Winter comes, Rudi has to leave town. Hedwig gets very lonely. Their idyllic life falls apart not because it is based on death and destruction, but simply because that is what happens! It turns out that being evil doesn't protect you from having a blah marriage or from experiencing loneliness and discontent.

It was a genuinely shocking move. You always expect these people to be getting some material or psychic dividends from their behavior, but really the thing about mass murder being just a job is that...it is indeed just a job! There is no fraternity, no special reward, not even an aura of power or respect.

I thought the movie was spectacular. So many of these movies try to humanize the victims, and I wonder if maybe that's a bad move. Nowadays everyone sees themself as a victim, nobody as a perpetrator. Both the Jews and the Palestinians right now see themselves as heirs to the mantle of victim-dom, and the Nazis too, for their part, also saw themselves as victims--finally recovering their honor after the "stab in the back" during WWI. Maybe it's better and more productive to imagine ourselves as perpetrators instead.

Speaking of productive things, over in notes I had a strange desire to share my most controversial opinion, which is that human beings are not animals. This was inspired by this Slate article, which makes the obvious gotcha joke at the end.

I just don't think human consciousness is similar to animal consciousness. Nor do I think humanity's role on earth is similar to that of even the highest animals. The entire concept of animal only makes sense in opposition to humanity. And 98 percent of the time, when people use the word "animal" they use it in a way that specifically excludes humanity. For instance, if I was to say, "Could an animal be convicted of murder?" most people would say 'No'. If I said "Do you think there should be an intelligence threshold for voting?" most people would say no, and yet if you asked "Should a hamster be able to vote?" they would also say 'no'. If you said, "I'm attracted to animals" they would be disgusted. If you asked "Can animals go to hell?" almost everyone would says no. If you asked "Would you trust an animal to drive a car?" people would say "No way." And on and on and on and on. There are actually very few situations where people consider "human" to be a subset of "animal".

Predictably, this was very controversial! I find that most members of the intelligentsia are scientific supremacists: they hold science to be prior and superior to other forms of human knowledge. The moment science lays claim to a sphere of knowledge (e.g. taxonomy), members of the intelligentsia become very aggressive about disavowing any lay or traditional perspectives on that topic. Scientific supremacists are also often (but not always) scientific materialists: they believe empirical study of reality is the only route to valid knowledge, and that the most valid form of empirical study is scientific investigation.

I'm not a scientific supremacist or a scientific materialist. I think the most valid form of knowledge is the personal, intuitive and pre-given. I think my intuition that humans aren't animals is a higher form of knowledge than the scientific understanding. Nor is my intuition uncommon. My three year old daughter has a sloth stuffed animal, but she insists he is not an animal, he is a human in a sloth suit. If you call him an animal, she gets very upset, because she knows that her relationship with Felix is deeper and truer than the kind of relationship a person can have with an animal.

The rejoinders to my note were what you'd expect: the divorce between the human world and the animal world leads people to regard animal life as lesser and as existing only for our pleasure--it lead us to use and consume animal life.

I would say that using and consuming animal life is quite natural. What is dangerous in modern humanity is not the fact that we have an instrumental view of animal life, but that our power over the Earth is so boundless that we possess the ability to seriously befoul our environment and cause the extinction of many of the animal species therein. As with many things, our newfound power may necessitate a revision of our naive understandings of certain phenomenon. This is happening right now, in real time, with regards to the concept of free speech: a significant number of people think that with new information technology, free speech is now passe, because tech companies are able to create speech so powerful and viral that human beings are no longer able to critically evaluate it. Obviously we all love free speech, but if it is in fact the case that human beings are unable to exercise their critical faculties, then free speech is already dead, whether we know it or not.

Similarly, when it comes to the question of human and animal life, we're obviously very attached to our own specialness, but one could certainly make the argument that the distinction between human and animal life is an artificial one--that our belief in our own specialness has become foolish and self-defeating and that we should, for instance, start allowing animals some say in how the Earth is governed.

This strikes me as being very suspect, however, because are we helping animals for their benefit or for our own? If it's for their benefit, then why do I care? And if it's for my benefit, then why do I need to pretend I'm doing it for theirs? In short, I am unconvinced by the notion that human supremacy is a useless or self-defeating belief: if anything I think human supremacy is the only true argument for the preservation of animal life. We want the Earth to prosper because we can only prosper if everyone does. But if our own prospering is not our first and foremost concern, then it would be impossible to escape the idea that out of all the "animals" alive on earth, it is human beings who do the most harm and, hence, are least deserving of life and happiness.

Am thinking of posting occasional It Came From The Archives posts. This one is pretty self-explanatory:

Fascinating piece. Agree with you on the overplaying of the ‘banality of evil.’

I agree with this:

"I'm not a scientific supremacist or a scientific materialist. I think the most valid form of knowledge is the personal, intuitive and pre-given. I think my intuition that humans aren't animals is a higher form of knowledge than the scientific understanding."