An interview with one of the most generous critics on Substack

It’s been such a privilege getting to know John Pistelli over the last year. He is the reason that I am on Substack. Like many writers, I am an assiduous self-googler, and I came across a mention of one of my essays on either his Substack or his Tumblr. I started stalking Pistelli, seeing what he was about. I’d been thinking for a while about potentially making the switch to Substack for Wordpress. I knew Substack had the heat, but I was worried that the culture would be transphobic.

And after listening to an appearance John made on Daniel Oppenheimer’s blog where they mentioned trans stuff in passing, I knew right away that there were some reasonable people on Substack.

I love the format of John’s newsletter. This guy has a PhD in English, right—and every week, he takes that week’s literary discourse topic, and he opines upon it at length in a series of posts called Weekly Readings. And…it’s all written in a very high style that’s impossible to describe, but luckily he gained a lot of new subscribers this week because he was mentioned in Ross Barkan’s newsletter, so he did me the favor of summarizing himself in a recent post:

Ross groups me with others who “may be classified, in an extremely broad way, as holding anti-woke sensibilities,” but, while this is accurate enough, it’s a characterization jeopardized by the nascent ideologies of the near future. I told someone privately that we would learn to miss wokeness, just as we are learning to miss the older form of oppositional (rather than regnant) MAGA. As the political air grows more and more frigid, we will remember both as having been extremely flawed vessels for (respectively) humane concern and human freedom.

This is so characteristic of John. It’s so perfectly the way he writes. But what’s most notable here is that he gives extremely generous readings to both ‘wokeness’ and ‘MAGA’. That’s really his characteristic critical move. He writes in a high-sounding register, but he combines it with a profound generosity of spirit, which comes through in all his readings.

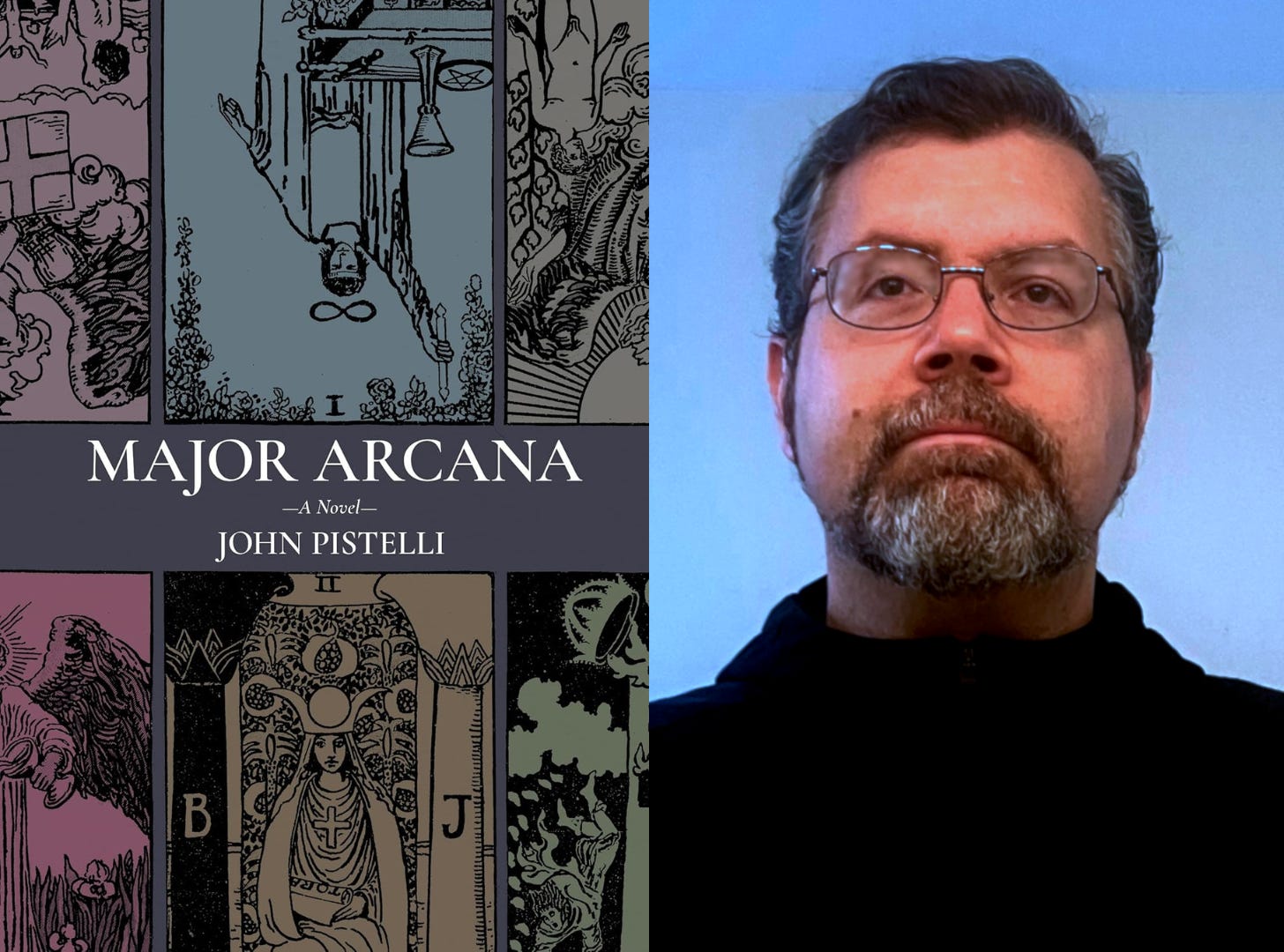

But what’s surprising is that the man who writes this way also writes extremely readable novels. I was so surprised when I opened Major Arcana to find that it has a powerful, unobtrusive omniscient narration that can easily say things like:

Then his grandfather died, just as he turned 12. The loss was not merely of a man, though who could ever replace the widower, his measured and precise movements, his fingers deft and careful when he turned a yellowed page, his hands reserved in their workman’s strength, restrained, as if not wanting to bruise a millimeter of flesh, even when he peeled an apple, his pointing finger that revealed the mystery of the world. The loss of the old man was the loss of a world: the dim apartment with its bare floors and old armchairs, its shelves massed with books, sacred and secular, the dust motes tumbling thickly in the lines of light cast by the slats of the blinds, the weighty credenza dense with candles and a picture of his long-dead wife, a pretty dark-haired woman in her long-gone girlhood.

It’s just…a great novel. Whatever you think novels ought to be, Major Arcana is at least within spitting distance of that thing. Which is kind of shocking, because I’m used to very-online literary figures writing things that are more overtly dismissive of form. In Pistelli’s case, the ambition isn’t to destroy or remake the novel, but to rejuvenate it.

Major Arcana is about this comic book artist, Simon Magnus, who is also a college professor. Early in the book, one of the students in Simon’s class kills himself, and Simon is somehow implicated. That’s the story that powers the book: Why did Jacob Morrow kill himself?

To that end, we get drawn backwards, into Simon’s own life, into the life of his mother, into the lives of his collaborators, and of their own children. It is an absolutely wild, looping, odyssey. And ultimately it’s about artistic creation as an act of will. About how the artist is able to impress the stamp of their personality onto the fabric of reality in a way that strongly resembles (and might even be the same as) magic. It’s something that John Pistell himself has been able to do, and I’m extremely happy that he’s managed to get this novel (which was originally serialized on Substack) into a form that is accessible by the broader public.

I knew that I wanted to commemorate the release of this book somehow, but I also didn’t want to commit to a full review, because John has reviewed my own book, and a reciprocal review just wouldn’t feel genuine. So instead I’m doing this interview, which is also somewhat of a review, but is different in some way that’s probably only apparent to myself.

The interview

This interview was conducted over Zoom. I typed notes as we wrote, and I didn’t record the interview. I hate email interviews because they feel very lifeless, but I feel self-conscious about my voice, so I don’t really want to edit an audio episode of the two of us talking. Hence, this transcript of a real-life call. I’ve largely edited out my own questions, but I’ve included them in italics when they’re necessary for context.

I live in Pittsburgh. I was born in Pittsburgh in 1982. I got my English degree at University of Pittsburgh. Then I moved to Minneapolis in 2006 to go to grad school, and I stayed there until last year when I moved back here. I did a lot of adjunct professing. Always wanted to be more of a writer than an academic, even though I did the PhD route. I self-published a few novels before this; I self-published Major Arcana too, before it got published by Belt.

I grew up without the internet; up until age 18, I would go on dial-up once a month. When I went to college, that's when I got online for the first time. I started writing essays about literary classics, and I built up a following that way, which I carried over to Substack. I had livejournal in 2002: I've been continuously blogging for the whole 21st century.

I had a livejournal for about five or six years that had a kind of prominence in radical left blog circles, around the same universe as Mark Fisher. But I discontinued it when I went to grad school, because I was like...they'll throw me out of grad school, or I'll get arrested for terrorism for my anti-war polemics. After I graduated and saw there was no hope on the academic job market, and I had stable adjunct gigs, I thought I'll try to build a following outside the institution. I was trying to sell a novel around 2013. I had some agents bite, but it never fully went anywhere. I just blogged until 2022 on Wordpress

You're one of the highbrow writers who is most comfortable on the internet. You not only write on the internet, but you almost never write about how it's destroying our minds.

I think ‘the internet is destroying our minds’ is a bit overdone. Maybe for younger people it is destroying their minds. But...my mind was already destroyed by TV. I can still read. I like it, I like to get away from my phone by reading.

Tell me about Major Arcana.

It wasn’t that long ago that in literary fiction there existed novels that were plotted and omnisciently narrated and had multiple viewpoints and had a narrative voice that could carry you through something of that length. Even in the 2000's that was more common, with Michael Chabon and writers like that. It went away with the dominance of the first-person and the autofiction. I wanted to bring that older model of the novel back.

It's a multi-generational saga, about something I always wanted to write about, because I grew up in the generation with the star comic book writer, who lived a mysterious life and practiced the occult and did horrible and mysterious things. I guess when I was younger, I thought I'd be one of those people.

I always thought it would be an interesting topic for a novel, about that kind of figure. Kavalier and Klay was about that older figure from thirties / forties comics—someone like Kirby. But I wanted to write a novel that was about the broader influence of a writer’s work. The idea that you might've in the nineties been writing something that was quite revolutionary for the relatively niche audience of comics books fans who were reading it. But that gets diffused through the culture, ends up being taught in college, and influencing Christopher Nolan and becoming first a counterculture, and then a part of popular culture.

Let’s talk about Simon Magnus’s gender performance. Because what I loved about this book was that it starts off and it’s seeming like it’s just a parody. That he identifies as nonbinary in order to satirize woke college students and force them to use his chosen pronouns, even though they know it’s not really genuine. But…as you read the book, you realize, there is something genuine here. That Magnus really does feel somewhat hurt by the way this campus culture forcibly genders him as a man, and that’s what he’s rebelling against.

It kind of begins feeling satirical of the woke moment, and then the last few chapters I'm beginning to satirize the anti-woke extremes. I didn't want it to be purely satirical. I wanted to talk about the question of gender, particularly in relation to the experience of artists. One of the themes of my essays and critical work is that it's difficult for modern artists to inhabit their gender normatively, because art is this thing where by its nature you're bringing the emotions of the private life into the public sphere. So if you're supposed to be female, you're transgressing that by coming out into the public sphere, under the terms of the gender binary. So if you're male, you're transgressing that by expressing all this emotion.

So I wanted to explore that and the way it interacts with peoples' spiritual commitments.

Simon Magnus is obviously bad to women throughout the book, but I talk about his early experience of cross-dressing, and with Ash Del Greco, I talk about how gender feels particularly imprisoning when you're young.

Many of the characters in this book are very well-read, and they undertake these high-brow courses of reading even while in their teens. Did you do a lot of highbrow reading when you were young?

I grew up on comics book and science fiction. I grew up on a lot of superman and batman. From that, I went to Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Ray Bradbury. And then I was reading Harlan Ellison, people like that. Then in late middle school I started reading the classics.

I fell in love with modernism first. I got into Joyce and Faulkner and Toni Morrison and people like that in ccollege. At the time, I thought long 19th-century novels were a little boring. My experience was a little like Ash Del Greco. I was into poetry and stuff like that, and I needed someone to tell me I should read Tolstoy.

I deliberately--I realized it would make the book feel a little strange, that all the characters were so well-read. I wanted to work against--there's this tendency in American literature. Hemingway, Faulkner, Toni Morrison, Steinbeck--they all say we are going to write about people who are close to the earth and all their wisdom comes from that. There's a neglect in American literature of people who read and intellectualize. so I wanted to work against that trend.

What was your experience serializing the book?

I started writing this book in January of 2023, and I started serializing it in March of 2023s. So I was always two months ahead of the serial. And some of it was imported from a prior attempt. I'd started writing a novel that didn't go anywhere, but there were some decent chapters.

It was interesting. The serialization itself wasn't the world's biggest success. I didn't get a lot of paid subscribers out of it. I got a lot of people who gave me subscriptions to support the ethos of what I'm doing, but in terms of actually reading, they said I’ll wait until it's a book. But there were a hard-core of readers who were asking questions and asking me questions about the process. Ultimately, I came to the attention of Ross Barkan, the journalist who wrote about it, and Anne Trubek, who published it.

One of the strangest things about talking to you, and about your online presence, is that you’re a self-published writer, but you really don’t seem particularly bitter about the publishing industry.

I'm so bitter about academia, that I don't have space about the publishing industry.

I just...it wasn't...nothing felt personal about it. All of my attempts to get an agent and go about it the right way happened before the culture war reignited, so I never really felt like the culture war was a factor. What was a factor, and was a bit frustrating, even in 2012 and 2015—there was such a desire to compete with TV. Can you make it more legible. Make the characters more likeable. Can you tone down the language, in the sense it was written in too high a register. I didn't feel like I was personally excluded from the publishing industry. I just didn't have an MFA, I didn't have the right connections, so I get it—there was nothing personal about it.

What about academia? There’s some bitterness there…

They made their own bed. My doctoral dissertation, as I described, was about academia destroying their own mission by making certain kinds of demands about art that it couldn't fulfill, that it had to be activist in certain way. And my work was about how art can have certain beneficial social affects. But not if you put it on the spot. So in letting that political readings of art get too rampant, they lost social trust.

Another thing that’s always struck me about your online presence is that you’re very generous. If something comes under your gaze, whether it’s Honor Levy or myself, you always give it the best, most generous possible reading. How did you develop that capacity?

It came to me gradually. Because when I started blogging in 2002, for the first five years, I did revel in the destructive / negative. That archive is gone, it'll never be seen. I did revel in hatchet job criticism and all that stuff that would become prominent on social media. I gradually saw that it wasn't productive. It kind of isolated you in a way. It gives you a cachet for a while, but then you become a prisoner of a certain kind of position that you can't really get out of. And I did become disturbed by the way it worked on social media, the destructiveness of the discourse. So I did kind of deliberately trying to not do that in my work. I've written a few ungenerous pieces, like I've made a lot of fun of Byeung Chul-Han. But I tried where I can to find the common ground, where the true things are. I think that makes it more more credible when you find the false things.

Almost alone amongst literary people writing online, you also seem fairly optimistic about the future.

I used to be down the line radical socialist. Between college and grad school was the Iraq war and 2004 election. It felt very apocalyptic. I understand when people today say the world is ending, but it felt that way to me 22 years ago. So I understand when people say it feels very urgent and something must be done. Now I've taken a position that's somewhat aloof, but I think many people are offended by it...I try to take this very aloof, cosmic perspective, which is offensive to people who are suffering now. But I was once very immersed the idea that all we ought to care about is people who are suffering now, and what that gave rise to in me are things that should not be rewarded or encouraged.

You're also quite an optimist about technology.

I'm trying that on. I reacted very negatively to the pandemic policy. I was very negative then. I thought we were going to be bio-scanned every second of our lives, and the doors of our smart apartments will lock if things are detected in our cells. I become very dystopian in the worst moments of the pandemic. I was very encouraged by the way that through democratic processes, we were able to avoid the worst of those things.

So I'm trying on techno-optimism now. In that way my essays are like my novels, in that I'm trying on a character to see how that feels. I am prepared for it to go disastrously and for us to end up in complete servitude, but what if it's not...what if it's like Oscar Wilde said and the machines do the ugly work for us and we are free to do beautiful things. What if that happened?

P.S. Here’s some order links for Major Arcana: Amazon / Bookshop.

What a generous interview! Re: what academia has done with literature, I really appreciate this: “my work was about how art can have certain beneficial social effects. But not if you put it on the spot. So in letting that political readings of art get too rampant, they lost social trust.”

Great interview, I've just asked my local library buy a copy of John's book!