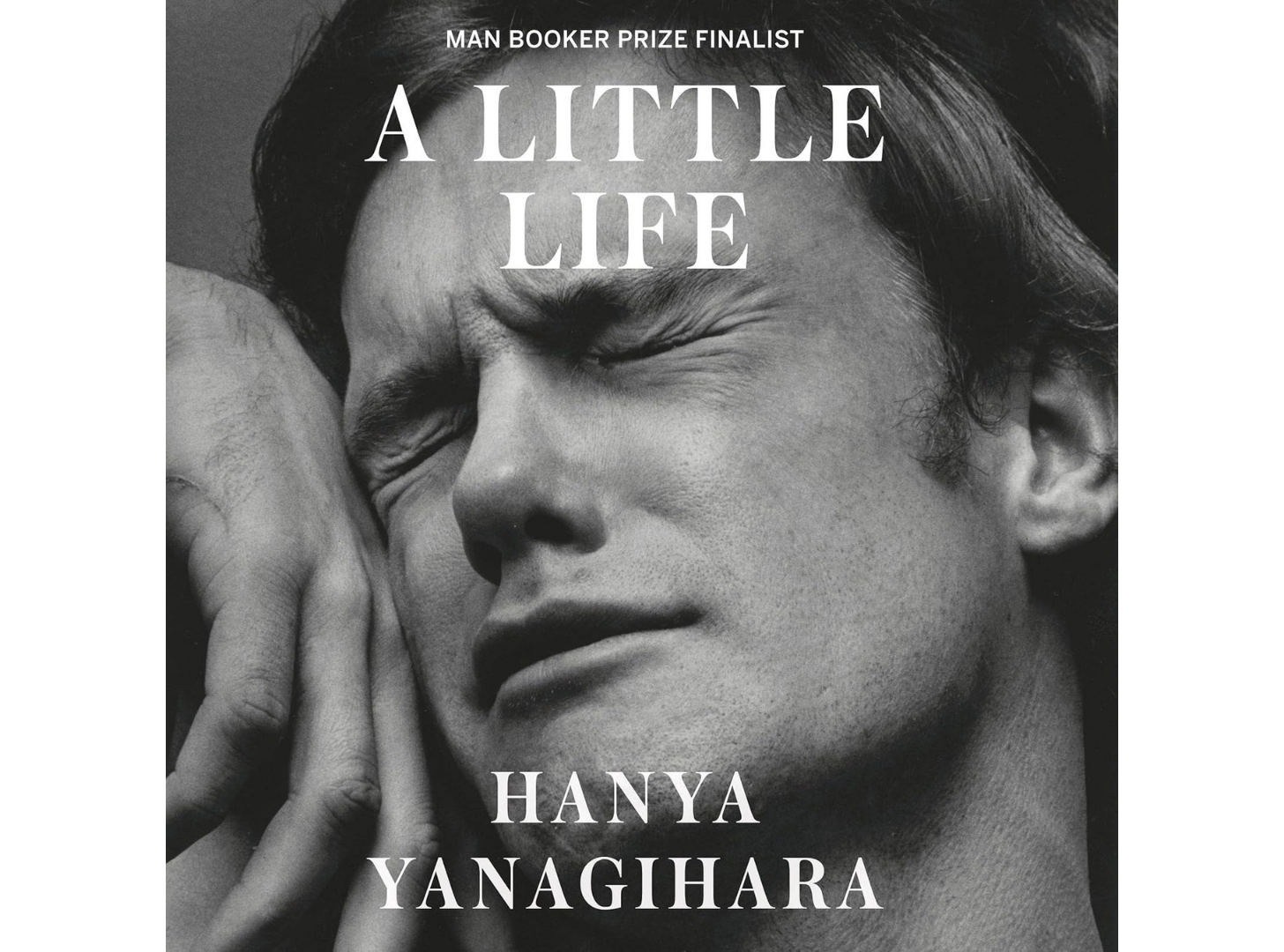

A manipulative masterpiece

A Little Life is one of literature’s greatest traps.

For the first hundred pages, this novel cozily describes a group of four college friends and their petty tribulations as they attempt to become successful members of New York’s creative class. But as the book progresses, it devolves into a Gothic saga of mental and physical abuse, self-harm, rape, and torture.

As we eventually learn, one of these four friends, Jude, is an orphan who as a child was beaten and sexually exploited by several groups of men, the last of whom hit him with a car and gave him severe spinal injuries that leave him in constant pain, which he can only alleviate by cutting himself.

But there’s another side to Jude. He is also a genius. He goes to college at sixteen. He gets a graduate degree in mathematics, and he is a brilliant litigator and a decent singer and baker. Jude is deeply insecure, childishly attached to his friends, and terrified of being rejected by them, even though they all adore him.

Over the course of this seven-hundred page novel, Jude’s story spirals out of control, becoming a bigger and bigger part of the novel. The central relationship is between Jude and his friend Willem. This guy, Willem, becomes a famous actor! He’s in all kinds of movies, has his face on billboards, becomes a bankable star. But he remains quite attached to Jude and eventually they start a romance and come out as gay partners, at considerable risk to Willem’s career.

A surprise hit

The story I’m describing seems like it’s probably bad, no? If presented with the description above, surely nobody would be willing to slog through this novel.

Two things about this book are astonishing. The first is that when it was released in 2015, the book became a hit! I don’t think it got a lot of publicity from its publisher, Doubleday, but word of its merits must’ve spread pretty quickly, because that year it got shortlisted for the Booker and the National Book Award. However, this book’s success went way beyond award nominations. People talked about it. I only read this book because my coolest writer friend sent me a text saying I had to read it. And then I convinced my friend Courtney to read it, and we still talk about the book to this day.

A Little Life came out only ten years ago but already has eight hundred thousand Goodreads ratings and has sold millions upon millions of copies. It got rave reviews in plenty of outlets. Garth Greenwell said in The Atlantic that it was the great gay novel. It was the rare union of commercial and literary success.

And the other weird thing about this book is that it’s actually good!

I know! I have no way of describing the appeal of this book to you. It is so gothic and baroque and sentimental, how could it be good? But…those three adjectives are just pejorative terms that posterity has assigned to styles that people used to genuinely enjoy. Once upon a time, if you said something was baroque, people would’ve said, “Actually, I love the maximalist and highly-ornamented nature of this object, because I live in the baroque era. Well, that name hasn’t officially been coined yet, but I definitely live in an era where we like baroque things.”

A Little Life seems like it’s from some other world entirely. I’ve just spent a whole week re-reading this book, and I’m dazed. It was such an overwhelming experience. There are lots of characters (almost all of them men) and lots of relationships. Initially this book is about four men. And in fact there is a whole section in this book about one of the characters, J.B., and his drug addiction. After that section, this character only reappears very intermittently! Another character, Malcolm, is a viewpoint character early in the book. We learn all about his father and mother and their interpersonal dynamics, and then all those family members fuck off, and we hardly see them again. We see a little of Malcolm himself, but not that much.

And then there’s the torture. There are hundreds of pages in this book devoted to Jude’s childhood abuse. There’s a whole interlude, very reminiscent of Lolita, where we see a pre-teen Jude being pimped out in motels by his guardian-figure, a former Catholic monk named Luke. And that’s only one of four distinct times that separate groups of people sexually exploit Jude before he turns sixteen. And each of those times gets its own section. In the final flash-back section, he’s held captive by a psychotic doctor who finally chases him down in a car, leaving Jude with permanent spinal injuries.

How could this be good? I have no idea. It seems unbelievable that this could actually be a good novel.

And some critics have indeed refused to believe in this little book. Christian Lorentzen wrote a negative review. So did Daniel Mendolsohn. So did Andrea Long Chu. They all said the same thing: what the fuck is this novel? Why does this Asian woman writer spend this novel torturing a group of gay men? What is going on here? This is not good. We don’t want to read this.

Great, that is their opinion. It’s a very understandable one.

But I do not share it. I’ve now read this novel twice! That is more times than I’ve read To The Lighthouse. I’m a notoriously harsh critic, an immense hater, and part of me expected that I’d resent this book on my second re-read and decide it’d been overrated after all. But no such thing occurred: I was absorbed and entertained.

Both positive and negative reviews of this book agree that its basic appeal, such as it exists, comes from the juxtaposition of glamorous, aspirational New York lifestyle with the darkness of Jude’s extreme mental pain and anguish. Sometimes the book is extremely glossy and sentimental, as in its evocations of fine meals, luxurious vacations, the acquiring and renovation of real estate, its numerous scenes set at parties, art exhibitions, or movie shoots, or, most touchingly, in its repeated odes to the power of friendship, as in the following scene where Jude gives a pep talk to a lonely kid he’s tutoring:

“You won’t understand what I mean now, but someday you will: the only trick of friendship, I think, is to find people who are better than you are–not smarter, not cooler, but kinder, and more generous, and more forgiving–and then to appreciate them for what they can teach you, and to try to listen to them when they tell you something about yourself, no matter how bad–or good–it might be, and to trust them, which is the hardest thing of all. But the best, as well.”

But there are also hundreds of other pages in the book, where the narration dwells in an equally loving fashion over Jude’s physical ailments, his failing body, his slow loss of mobility, his repeated cutting and hospital stays, his intense loneliness and self-hatred, and his frequent meditations upon the past lifetime where he was beaten and raped by men who were supposed to care for him:

Brother Luke usually didn’t have sex with him if he’d seen clients earlier in the evening, but they always slept in the same bed, and they always kissed. Now one bed was used for the clients, and the other was theirs. He grew to hate the taste of Luke’s mouth, its old-coffee tang, his tongue something slippery and skinned trying to burrow inside of him. Late at night, as the brother lay next to him asleep, pressing him against the wall with his weight, he would sometimes cry, silently, praying to be taken away, anywhere, anywhere else.

This paragraph detailing the life of the nine-year-old Jude would probably be the most shocking paragraph in most novels, but in this one, it doesn’t come close. There are many dozens of pages describing these sorts of sexual encounters.

The first time I read the book I thought the sexual torture and cutting were excessive. I, like most readers, was much more invested in present-day Jude’s life with his friends. These torture chapters felt like a punishment, of sorts.

Now, my second time, I don’t know if I agree. I think maybe they were necessary. Maybe they were perfect. The book forces you to endure the pain in order to get back to the pleasure. And maybe the pleasure would be dull without the pain. Moreover, because Jude’s life is so good in the present day–everyone loves and respects him so much–that it doesn’t make sense that he’d be so sad. So you’ve really got to see, in gruesome detail, why he’s so sad, why he’s so upset.

Not the choice I would’ve made. But maybe her choice was better. The book undeniably succeeds, and I have to think all this torture has something to do with that success.

This novel resembles fanfic

One thing that’s sometimes been mentioned is that this book strongly resembles a genre of fanfic called hurt-comfort. I don’t know much about this. I’ve never read fanfic myself, but I am told that a hurt-comfort fic is about one man who’s in pain being comforted by another man, and that it often trafficks in gothic, over-the-top imagery and emotions.

I’m not saying Hanya Yanagihara wrote fanfic, but she was clearly drinking from the same well.

But that’s okay. That just describes the phenomenon of a particular type of fiction existing and having some appeal. Jane Eyre is the same. Saintly Jane goes through so much! Even in the first quarter of the book there’s a TB outbreak at the school and all her friends die. Many of Dickens stories traffic in similar tropes, they’re about people caught up in rough circumstances and victimized by society. Think of poor David Copperfield in the ink factory. Or the story of Amy Dorrit, born in debtor’s prison. These stories aim to evoke strong reactions, and they do.

Now...is that good? I don’t know. But, personally, when I read a novel I like to feel something. I like to feel as if something is happening. With most literary novels, I feel nothing. No interest. Just boredom. With A Little Life, I wasn’t bored. It’s a singular, unforgettable experience. I found it enjoyable, although the nature of that joy is difficult to describe. It’s certainly a very sensual joy. Reading this book unleashes difficult emotions. It’s like watching a horror movie or a romance–it’s not a cerebral reading experience at all. When you read A Little Life, you can feel it acting directly upon your nervous system in a way quite unlike any other contemporary literary novel you might run across.

A person might ask whether there’s any artistry involved in creating A Little Life. I don’t really know how to answer that. Certainly I don’t think creating this effect is simple. A Little Life commits very strongly to its exterior story, about the group of four friends, and if their little interpersonal dramas didn’t feel so real and comfortable, the book wouldn’t work. The genius of the novel comes from the fact that it so easily could’ve been a cosy group-of-friends story, but instead the author insists on slashing that story to ribbons and letting it be interrupted by these Gothic elements. My sense is that in less skilled hands, the book wouldn’t have worked at all. Either the friendship or the torture stories would’ve flagged, growing dull, and they wouldn’t have created the combined effect that makes the book so explosively powerful.

At this point in a review one typically falls back on that old standby: the writing. Appealing to “the writing” is the ultimate get-out-of-jail free card. This book is saved by its writing! The sentences are so melodious, so gorgeous, so lyrical! But...in this case...because the emotional experience of reading the book is so intense, and because it’s such an immersive novel, you genuinely don’t notice the writing. I think the writing is good, but the whole book is told with a certain flatness and level of narrative distance that’s meant to make the writing disappear. This is not a book where any sentences will stand out in particular, but to me that is good writing. Showy writing is not always good. Oftentimes it breaks immersion. A novel is a whole, and the writing should be in service to that whole.

It’s also somewhat-possible that A Little Life isn’t actually a great example of a hurt/comfort fiction. After all, I’ve never read any fanfic. Maybe there are H/Cs out there that are a thousand times more intense than A Little Life, and this book is only giving me a pale watered-down version of what a thirteen-year-old would get from a week of browsing AO3. I can’t say.

Return of the sentimental novel

However I do think it’s a bit reductive to compare A Little Life to fanfiction. It seems more likely, to me, that both H/C fic and A Little Life are working within the sentimental-fiction tradition that, although it’s not taught in school, remains vital and widely-read.

After all, the sentimental novel was a whole genre, primarily read and consumed by women, where saintly protagonists are subjected to various forms of torment, and many of these novels, in particular Little Women, Les Miserables, and the works of Charles Dickens, are quite popular with contemporary readers.

There is a whole canon of taste for evaluating sentimental literature. It obeys different rules. I’ve now read a lot of 19th-century sentimental novels, and some are better than others. Usually, the problem is that the author is afraid to let the character truly suffer. The protagonist of the 1850 best-seller, Susan Warner’s A Wide, Wide World, is also an orphan, but her main issue is that her aunt is quite crotchety and mean. That is difficult for this girl, yes, but the conflict is sufficiently minor that the book starts to feel dull.

Sentimental authors tend to care for their characters. They want good things for them. And why would good things not happen for someone who’s so good? The best-selling novel of the 19th-century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, had an answer for that: It was because of slavery. Slavery was evil. And the evilness of slavery was revealed by how it tortured and humiliated the saintly Tom. And the book came pre-packaged with a solution; to save the Toms of the world, you must end slavery.

When seen in this particular canon, A Little Life genuinely feels like a bit of an outlier, because most of these books existed in an explicitly-Christian universe where the protagonist’s saintliness would be rewarded for its own sake. In a typical sentimental novel, you know that the characters are saved. You know, even if they die in the end, that their life had some meaning.

With A Little Life, you don’t know that. You’re without a net. It’s amazing that Yanagihara could’ve sustained for 700 pages that basic uncertainty about whether this man’s suffering has any meaning at all.

It is fascinating that this author could torment this character when they also love the character so much. This is a character who everybody in this book immediately adores. His law professor formally adopts him as his son. His best friend, who identifies as straight, goes gay for him. He sees a medical resident one time in the ER, and this resident reorganizes his whole career around helping Jude with his medical problems. One of Jude’s college friends, who is rich, offers him a sweet-heart deal to help him buy a beautiful condo. The list of favors and rewards is endless.

But...then there’s also these other people who torture and rape Jude.

How could both things exist in the same universe? How could this be a universe where good things effortlessly flow into Jude’s lap, and, in this same universe, he’s constantly being beaten and sexually traumatized—by the way, if you ever start thinking that maybe Jude’s pain is only in the past, he also gets into a relationship in the present day of the story, with Caleb, who proceeds to beats and humiliate him!

What seems clear to me is that there’s a genuine and coherent artistic vision that underlies all of this, and that this vision is deeply troubling. In A Little Life there is an evil that constantly lurks at the edge of Jude’s life. He cannot protect himself, even with all his intelligence and wealth and privilege. Eventually, his movie-star lover Willem dies in a car crash, and after a protracted effort to attempt to find meaning in his life, Jude kills himself.

Honestly, the book insists so strenuously on the idea that Jude’s life isn’t worth living that I found myself arguing the opposite. Come on, Jude. If you stick around, something good will happen. But his own past shows that’s not always the case. Often bad things happen—usually in the form of a seemingly-kindly man who rapes you.

If that joke seems in poor taste, well...that’s the novel. The whole novel is a violation of prevailing norms about taste. It’s shocking that it was received so well and got the awards attention that it did.

To be clear, I am very happy that it got attention. I am happy to have read the book. I never would’ve read this novel if cool people hadn’t extolled it, and I enjoyed the experience of reading this book.

I’m tempted to engage right now in some kind of amateur sociology and make some case as to why critics and awards juries embraced this book, when it’s really not the kind of book that they typically love. Maybe they really wanted to reward a gay book or an Asian author? But, in the end, sociology is only necessary to explain the success of bad books. When a good book succeeds it’s not mysterious to me: it succeeded because it was good.

And with A Little Life, we also know that it was not intended to be a big book by its publisher. It was a word-of-mouth hit, amongst people like me, who enjoyed the book and thought our friends might enjoy it too. The book is so strange that it made a conversation piece: we enjoyed talking about it, and what we liked was that it was so different from other books. Critical opinion really coalesced after-the-fact, in recognition of this book’s appeal amongst a certain kind of person. This was the Twitter era, so buzz built quickly enough that awards juries took notice. Everything worked out the way it was supposed to. People liked this book because it was genuinely strange and startling and different, and as a result the book was a critical and commercial success.

Now...will it last? I don’t know. When I asked about the novel online, I got dozens of responses from people who’d read and loved the book, but many respondents seemed to feel like the book’s critical reputation had decreased over the years. As you can see, it’s a book that’s easy to critique: it is melodramatic and wallows in Gothic misery. And then there’s the representational politics of a woman spending an entire novel torturing a queer man.

Unfortunately, the only answer to these critiques is that the novel retains an undeniable power. Some percentage of people who read this book will love it. And if enough of those people are spurred, ten years from now, to write articles in its defense, then its place in literary history will be safe for at least another generation.

“The book forces you to endure the pain in order to get back to the pleasure.” Where was that pleasure? As you point out, the first pages tricked me into thinking I was getting a story about 4 friends and instead I endured hundreds of pages of monotonous, repetitive descriptions of self-harm and mental illness—not bad as subject matter but only used in this book as some kind of hook. That was the trick. The best I can say is I hated the story and the writing wasn’t great and I couldn’t stop reading it and would recommend to no one.

Also: nothing in this book is reminiscent of Lolita: she was not pimped out, but more importantly, Yanagihara’s writing lacks any of the subtly, cleverness or humor that suffuses Nabokov. You are right the ‘evocations’ in this novel are its hallmarks and the author adeptly mimics the stereotypical interest of gay men in food, art, travel, cloths. But how many times do we have to hear about a new meal, a new trip, a new encounter that does absolutely nothing to advance the narrative and is delivered in prose that belongs in Bon Appetit or an in-flight magazine? Why the hell I finished this book I still have no idea.

IMO it’s kind of crazy to mention this novel in the same breath as Dickens novels. This is an extreme trauma novel about an horrific case of child sexual abuse and life long suffering. Yes, Dickens wrote about people in tough circumstances. But his characters represented not uncommon hardships, and he aimed to expose social ills. I don’t buy the idea the idea that these two writers drew from the same well.